By Mike Darwin

A Flash of Insight

One of the most fundamental insights I’ve ever had came when I was in Rome, and also reading a very good biography of Leonardo da Vinci,1 in preparation for a visit to Florence. Da Vinci spent most of his career designing war machines, and trying to reroute the Arno River for military advantage. As I looked at the remains of the awesome Ancient Roman engineering around me, and thought of da Vinci, it occurred to me that one of the most powerful and off putting military advantages that could have been deployed, in either Ancient, or Renaissance times, would have been hot air balloons.

Hot Air Balloons in Ancient Rome?

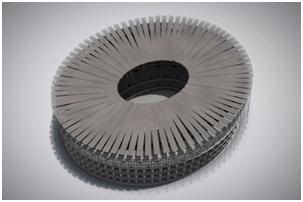

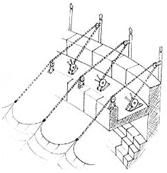

Lighter than air craft are very easy to build, and both the Ancient Romans and the Renaissance Italians had the materials, the wealth, and the technology. The Colosseum was covered with canvas awnings, the Velarium,2 that were operated by a complex series of ropes and pulleys, and the Roman’s were superb canvas makers and produced the material in copious amounts to use for ships’ sails. Why didn’t they develop lighter than air flight – and why didn’t Leonardo? The Montgolfier brothers came up with the idea while lying beside a fire and watching hot ash and embers float upwards – and they thought about this in a military context – namely how to take Gibraltar from the British.

Lighter than air craft are very easy to build, and both the Ancient Romans and the Renaissance Italians had the materials, the wealth, and the technology. The Colosseum was covered with canvas awnings, the Velarium,2 that were operated by a complex series of ropes and pulleys, and the Roman’s were superb canvas makers and produced the material in copious amounts to use for ships’ sails. Why didn’t they develop lighter than air flight – and why didn’t Leonardo? The Montgolfier brothers came up with the idea while lying beside a fire and watching hot ash and embers float upwards – and they thought about this in a military context – namely how to take Gibraltar from the British.

Selection Bias and the Arc of Technology

That got me thinking about all sorts of technologies, and why they were not developed far earlier, given that the minds, the tools, and the ancillary technologies were often all clearly in place. It was then that I realized that to a great extent we are, all of us humans, optimists and technological prophets of the most lunatic sort; in no small measure because all we know, by experience, is that we have survived, and that we have triumphed (so far). Similarly, most people in the West (and especially cryonicists) see human history as relentlessly and inevitably progressing, in large measure because we ourselves are the product of a civilization that has survived and progressed – and that has done so to an astonishing degree – in an equally astonishingly short period of time.

That got me thinking about all sorts of technologies, and why they were not developed far earlier, given that the minds, the tools, and the ancillary technologies were often all clearly in place. It was then that I realized that to a great extent we are, all of us humans, optimists and technological prophets of the most lunatic sort; in no small measure because all we know, by experience, is that we have survived, and that we have triumphed (so far). Similarly, most people in the West (and especially cryonicists) see human history as relentlessly and inevitably progressing, in large measure because we ourselves are the product of a civilization that has survived and progressed – and that has done so to an astonishing degree – in an equally astonishingly short period of time.

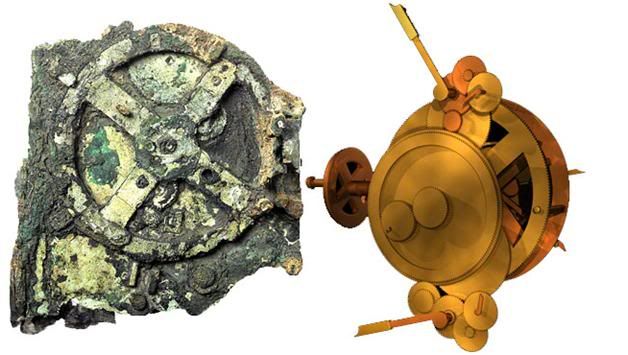

The Antikythera Mechanism (above).

The Antikythera Mechanism (above).

Unfortunately, there is nothing in our current understanding of human history, let alone physical law, which mandates technological advance, let alone specific kinds of technological advance, as inevitable. To understand this, it is only necessary to look to the past, to the long history of scientific and technological advance that was, and wasn’t to be. To do that is to understand that there is a fundamental difference between technological possibility, and practical inevitability. By looking at the past, and applying the expectations we have of the present, it is possible to perceive a more sobering and cautionary reality.

In 1901, in the remains of a sunken ship just off the coast of Antikythera, an island between Crete and the Greek mainland, divers harvesting sponges recovered the remains of what had once been a wooden box, containing what appeared to be a complex clock-work mechanism.3 The shipwreck has been unequivocally dated to ~80 BCE. For nearly 60 years the artifact was largely unappreciated; it was encrusted in a hard calcareous mass, and what little remained of the metal parts of which it was once comprised, had been converted into what might reasonably be described as metal-doped casts, or ‘fossils’ of the original mechanism. Thus, it was not until the advent of sophisticated examination techniques, such gamma ray imaging in the 1970s, and more recently, gamma ray tomography, that the structure of the original mechanism could be determined.

As it turns out, the artifact recovered from that ship just over a century ago, and now called the Antikythera Mechanism, was about as incredible as if a 16th century pocket watch were to be found today in a sealed Pharaonic tomb from Ancient Egypt. The Antikythera Mechanism has forced a complete re-evaluation of the technology of the ancient world. The device contained 32 gears, assembled into a mechanism that accurately reproduced the motion of the sun and the moon against the background of fixed stars, with a differential drive giving their relative position, and thus the phases of the moon.4 More recently, it has been discovered that device also integrates eclipse prediction with cycles of human institutions, most notably the Olympics!5

The technology used to produce the Antikythera Mechanism rivals that used in the best 16th century clocks, and the understanding of planetary motions embodied in the workings of the device suggest that some form of the calculus may have been in use by its makers. It is also clear from the complexity and precision of the device that it was not a prototype, but rather represents a well developed, and arguably a mature technology, which must have had other applications. In short, its elegant mechanism whispers across the millennia about what could have been and what, from our perspective and experience, seemingly should have been the follow-on to such scientific insights and technological capabilities. Why didn’t the Ancient Greeks invent timekeeping devices – why did the mechanical clock take centuries more to be born?

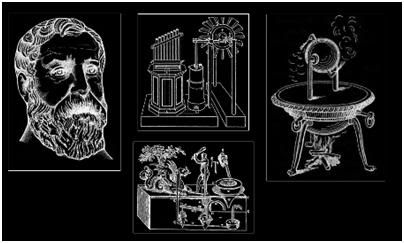

Hero of Alexandria and his inventions; (clockwise) the wind-wheel, the aeolipile, and complex automata used in temples and as public monuments. Images courtesy of the Wikimedia Commons

Hero of Alexandria and his inventions; (clockwise) the wind-wheel, the aeolipile, and complex automata used in temples and as public monuments. Images courtesy of the Wikimedia Commons

That the technological revolution, ‘our’ technological revolution, did not proceed from the Antikythera Mechanism might seem more reasonable if there were no other similarly remarkable developments occurring at the same time. However, Hero of Alexandria (10–70 CE) was well known for constructing complex automata, had powered a pipe organ using his wind-wheel (windmill) and developed a variety of steam driven devices using his aeolipile; a primitive turbine type steam engine with surprising motive capacity.6 From our vantage, it would seem not only reasonable, but prudent, to speculate with confidence about the technological capabilities that would (seemingly inevitably) flow out of these insights, coupled with the robust base of engineering skill that made them possible in the first place. And yet, the industrial and the technological revolutions did not proceed from these insights, and while many reasons have been put forth, the truth is that all technological advances are dependent upon a complex mix of social, political and environmental factors which we still do not understand, and thus cannot predict.

The ‘mundane’ observation that caused Joseph-Michel Montgolfier (1740 –1810 CE) to invent the hot air balloon7 was just as accessible to the Romans of ~400 BCE, as were the materials and technologies required to construct human carrying hot air balloons. Certainly, the same motivations were present in both cultures at both times: Joseph Montgolfier was contemplating how to successfully assault the British fortress of Gibraltar, which had proved impregnable to the French by both sea and land, when he noticed how floating embers from a fire he was laying next to were carried aloft and over great distances; giving him the idea of lighter than air flight.8 The Romans, a military people with similar problems, as well as a love of spectacle and a penchant for technological innovation in war, could just as easily have developed lighter than air manned flight – and yet they did not. There are no Roman frescoes of hot air balloons, whether for war or celebration, drifting over the Empire’s capital.

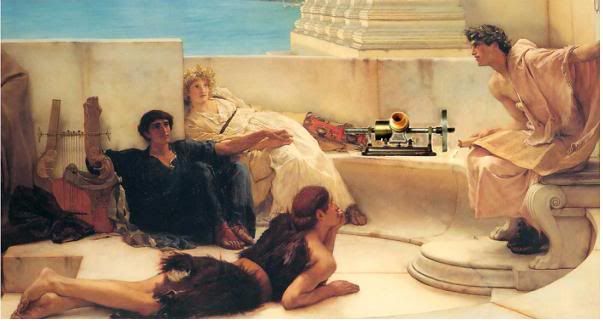

How would the technological arc of the ancient world have been changed if Archimedes, and not Edison, had invented the phonograph? Image adapted by the author from Sir Alma Tadema’s ‘A Reading from Homer,’ courtesy of the Wikimedia Commons.

For that matter, either Hero, or Archimedes of Syracuse (287- 212 BCE)9 before him, could quite conceivably have invented the phonograph. It is a simple analog mechanical device which requires the same kinds of recording media; wax or metal foil wrapped cylinders or plates (wax tablets were then in universal use by the Greeks as reusable writing slates, and gold foil was commonplace, if expensive). To complete it, all that was needed were a needle stylus, a deformable diaphragm of thin metal, or tanned hide, a sound concentrating horn, and the almost ridiculously simple cranking mechanism used by Edison for his prototype model. Edison’s invention of the phonograph in 1878, and all the subtle and yet profound social and technological effects that emanated from that discovery, could have come at almost any time in human history, from ~400 BCE on. It is not difficult to envision Archimedes, the inventor of the water pump that bears his name (the Archimedes screw), the designer of the mammoth ship the Syracusia, and the discoverer of hydrostatics, sitting amongst a group of lazy ‘Greeks’ on Syracuse, while declaiming the wonders of his latest invention, the phonograph.

Debased Social Choices as an Obstacle to Adoption of a Transformative Technologies

The past century, so recently closed, is rich with examples, both poignant and tragic, of technological possibilities not realized. On 1 September 1939, a decision was (in effect) taken by our species to spend five trillion dollars[1] and expend ~72 million human lives. This decision was followed in 1947, and repeated at intervals until 1991, to expend an additional ~12 trillion dollars, and perhaps another 1-2 million human lives. These ventures are known today as World War II, and the Cold War[2], respectively. In the midst of the first of these costly escapades, on 15 March, 1944, the architect of the German V-2 rocket, Wernher von Braun, was arrested by the Gestapo on charges of high treason for having privately expressed regret, after dinner at a colleague’s home one evening the previous October, that he and his team were not working on a spaceship, and that von Braun felt the war was not going well.10

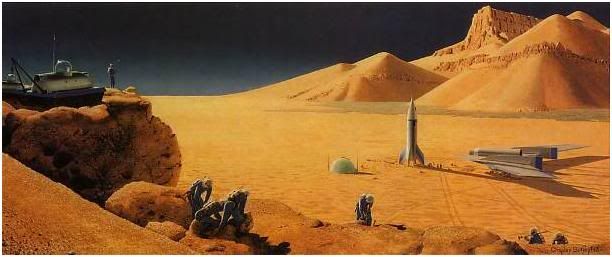

Artist’s Chesley Bonestell’s vision of von Braun’s plan to reach and colonize Mars, from Collier’s magazine, 1952.

In fact, von Braun was engaged in designing and building the V-2, and much more sophisticated rockets, solely because he wanted to achieve the exploration of space; both personally and for the human species.11 Throughout the war he had spent what little free time he had laying out the technological basis for a systematic program to reach and colonize the moon and Mars. In 1948, von Braun laid out these detailed specifications and they were subsequently published in his book Das Mars Projekt (The Mars Project),12 in 1952-3. Forty-two million Americans saw beautifully illustrated and highly detailed explanations of this plan on television on the Walt Disney Show, and many millions more saw the same plans in print in Collier’s magazine, beginning in February 1952 and continuing through March of 1954.13

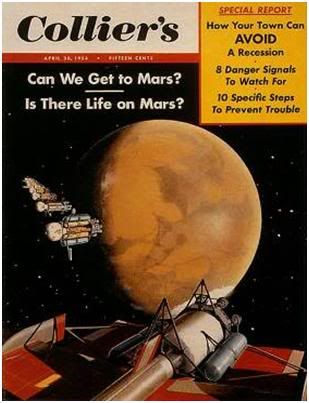

The cover of Collier’s magazine 30 April, 1954 which contained the articles ‘Can We Get to Mars?’ and ‘Is There Life on Mars.’

Von Braun’s proposals also received wide circulation outside the US in a broad range of Western media, and notably, there were no serious scientific or engineering criticisms of the proposals. In hindsight, it seems clear that if humanity had decided in 1939 to colonize space, instead of expending ~$17 trillion and ~74 million human lives on war and destruction, we would have reached the moon in a robust and durable way by no later than the mid-1950s, and would now have well established, and very likely self-sustaining outposts on the moon and Mars. We would thus now be in the position of having substantial insurance against both technological collapse and the possible extinction of civilization (if not the species itself).

The technology required to credibly begin this effort existed in 1939, and the cost in dollars (and certainly in human lives) for its realization would have been vastly lower than those that were suffered prosecuting WWII and the Cold War.

And yet, none of these things happened. It is, of course, possible to speculate endlessly in this manner, asking, “what if,” in countless situations where a technology was developed and not exploited, or was not developed when it easily could have been. It has been argued that our position in the opening decade of the 21st Century is unique: that having let the technological genie out of the lamp by discovering the scientific method and developing the printing press and mass production, we are now assured of relentless progress towards human suspended animation, practical biological immortality, and a mature and highly capable nanotechnology.

Perhaps this is the case. However, the examples of our past, particularly of our recent past – of chance and choice frustrating our expectations of technological advance – should instruct us that inevitable does necessarily mean immediate or even foreseeable, advance. Fifty-seven years later, we are still waiting for our tickets to the moon and Mars.

The Future That Wasn’t: Failure to Perceive Hidden Costs and Risks

Two other entangled obstacles to technological inevitability must also be considered: unappreciated psychosocial reservations and genuine, but unappreciated hazards that either slow, or virtually inhibit the adoption of what would otherwise be hugely transforming technological advances.

As a child, I was told about what my future would be like and how much better it would be in almost every way, technologically, from the world I then inhabited. I was, literally, a child of the atomic age, and the molecules in the DNA of my brain still bear the 14Carbon isotope signature of the open-air nuclear testing era, just as surely as my bones, made radioactive in my infancy and childhood by the Strontium 90 (90Sr) in the milk I drank are still, ever so slightly, more radioactive today, than are those of people born before, or after, the era of atmospheric nuclear weapons testing.14,15

But beyond these physical stigmata of the atomic age, my mind bears the stigmata of a world promised, but never delivered. Scientists and laymen alike were quick to understand the truly staggering potential benefits of what we now call nuclear power. Countless pronouncements were made that the arrival of an era of cheap, clean, safe, and virtually unlimited electric power was at hand. Electricity generated by ‘atomic power’ and nuclear fusion, we were told, would be so inexpensive to produce that it would not even be worth the expense of metering its use to bill the customer for. People would simply play a flat rate for the service, as is the case for long distance or computer telephony today. In a speech given by Lewis L. Strauss (1896-1974), Chairman of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission to the National Association of Science Writers, in New York City on September 16th, 1954, Strauss commented on how scientific research then underway would transform life for the next generation of Americans, the generation that would be born in then and in the coming decade, my generation:

“Our children will enjoy in their homes electrical energy too cheap to meter…will travel effortlessly over the seas and under them and through the air with a minimum of danger and at great speeds, and will experience a lifespan far longer than ours, as disease yields and man comes to understand what causes him to age.”16

At about the same time as Strauss made this pronouncement, the Ford Motor Company developed a concept car called the Ford Nucleon. The Nucleon was to use an ‘atomic power capsule,’ in effect an atomic battery, located in the rear of the car which charging stations would switch out for a fresh one every ~ 5,000 miles of driving time.17

At about the same time as Strauss made this pronouncement, the Ford Motor Company developed a concept car called the Ford Nucleon. The Nucleon was to use an ‘atomic power capsule,’ in effect an atomic battery, located in the rear of the car which charging stations would switch out for a fresh one every ~ 5,000 miles of driving time.17

The Santa Fe Railroad, then as commercially important and as technologically credible as Apple or Microsoft are today, anticipated fission reactor powered trains within 20 years, and ran ads in national magazines featuring a youngster only a few years older than me, asking to buy a ticket on an atomic powered version of the Super Chief which was then the preeminent way to travel across the country from Chicago to Los Angeles, in both speed and comfort.

The Santa Fe Railroad, then as commercially important and as technologically credible as Apple or Microsoft are today, anticipated fission reactor powered trains within 20 years, and ran ads in national magazines featuring a youngster only a few years older than me, asking to buy a ticket on an atomic powered version of the Super Chief which was then the preeminent way to travel across the country from Chicago to Los Angeles, in both speed and comfort.

So what went wrong? Were these predictions based on erroneous assumptions about was both possible and economical? The answer to that question depends a great deal upon what kinds of risks and responsibilities you are willing to accept as a society. In 1974, Medtronic, the world’s leading manufacturer of cardiac pacemakers, then and now, released the Laurens-Alcatel Model 9000 pacemaker.18 It was a nuclear powered device that used a tiny thermopile powered by 2 to 4 curies of plutonium-238 (with an 88 year half-life). As the term “thermopile” implies, heat from the decaying plutonium was used to generate the electricity that powered the device. There are an estimated 40-50 people in the US still alive with an implanted Laurens pacemaker. Thirty years later, these devices continue to operate flawlessly in those patients who remain alive with them. No doubt, those few of the devices that have escaped destruction will outlast their owners by many decades, if not a century or more.[3] A prototype power supply for a total artificial heart, containing 50 grams of plutonium, was also demonstrated at around this time.20

So what went wrong? Were these predictions based on erroneous assumptions about was both possible and economical? The answer to that question depends a great deal upon what kinds of risks and responsibilities you are willing to accept as a society. In 1974, Medtronic, the world’s leading manufacturer of cardiac pacemakers, then and now, released the Laurens-Alcatel Model 9000 pacemaker.18 It was a nuclear powered device that used a tiny thermopile powered by 2 to 4 curies of plutonium-238 (with an 88 year half-life). As the term “thermopile” implies, heat from the decaying plutonium was used to generate the electricity that powered the device. There are an estimated 40-50 people in the US still alive with an implanted Laurens pacemaker. Thirty years later, these devices continue to operate flawlessly in those patients who remain alive with them. No doubt, those few of the devices that have escaped destruction will outlast their owners by many decades, if not a century or more.[3] A prototype power supply for a total artificial heart, containing 50 grams of plutonium, was also demonstrated at around this time.20

Soviet-era RTGs that have been vandalized by thieves looking for valuable, non-ferrous metals resulting in the release of radioactive 90Sr into the environment.

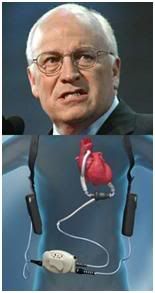

In the former Soviet Union, compact nuclear ‘batteries,’ Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs), typically powered by 90Sr, were in moderately wide use to provide electric power and heat for a wide range of applications – including serving as the electricity source for remote lighthouses in the arctic.20 Well over a thousand of these devices were deployed. So, there can be no doubt that this technology was not only feasible – it was a demonstrated reality.  Had it been pursued as aggressively as the development of say, the transistor or the lithium battery, it would be omnipresent in our daily lives. Laptops, flashlights, and other portable electronic devices would effectively never run out of power, with their lead and titanium encased ‘nuclear batteries’ being handed from one generation to the next. Arguably, most electronic devices would now have self-contained RTGs, freeing us of the frustrating nuisance of cords, cables and the infuriating lack of a power point where and when we need one. And of course, former Vice President Cheney would not now be tethered to the cumbersome and short-lived battery pack (~5 hours) to power his left ventricular assist device (LVAD)21 – nor would he face the near certain (and likely eventually fatal) risk of infection from the power cable that connects the vest-worn external batteries to the centrifugal pump implanted in his chest.

Had it been pursued as aggressively as the development of say, the transistor or the lithium battery, it would be omnipresent in our daily lives. Laptops, flashlights, and other portable electronic devices would effectively never run out of power, with their lead and titanium encased ‘nuclear batteries’ being handed from one generation to the next. Arguably, most electronic devices would now have self-contained RTGs, freeing us of the frustrating nuisance of cords, cables and the infuriating lack of a power point where and when we need one. And of course, former Vice President Cheney would not now be tethered to the cumbersome and short-lived battery pack (~5 hours) to power his left ventricular assist device (LVAD)21 – nor would he face the near certain (and likely eventually fatal) risk of infection from the power cable that connects the vest-worn external batteries to the centrifugal pump implanted in his chest.

What a wonderful world it would be – except for one small problem: the fundamental inability of most humans to handle such technology responsibly. There can be no doubt that had these nuclear technologies been so universally applied, we would currently be awash in uncontained and highly lethal radioactive material. Humans are simply not diligent enough, smart enough, and above all long lived enough, to be trusted with such dangerous materials, even though the benefits are both enormous, and abundantly clear. Even in the case of large, well designed nuclear power generating facilities, a major (and all too legitimate concern) is the deliberate compromise of the reactor containment structure to facilitate the release of radioactive materials for purposes of war or terror. Or what is worse, the diversion or deliberate use of the reactor fuel, or byproducts, to produce nuclear weapons. Crazy and irresponsible civilizations have no business using such technologies, and that is the primary reason why their use has been restricted, or prohibited altogether, in ours.

Where their use it is deemed worth the risk, or there is no alternative, the precautions required to make such use tolerable have proved staggeringly expensive. Atomic trains, planes and automobiles, as well as plutonium powered artificial hearts, and low cost and highly reliable electricity generated from nuclear fission, are all eminently doable – and would be highly cost effective if people handled these technologies with the high degree of responsibility they demand. If only we could change our natures such that our most powerful insights could not be deliberately perverted to do harm and wage war. Alas, that is clearly not in the cards any time soon.

But the pace of technological advance has not been slowed solely as a result of the actual (but unforeseen) risks inherent in novel technologies such as nuclear energy. Indeed, in the case of fission reactor generated electricity a significant cause of delay, or even abandonment of the technology, has been psychosocial. France has long been known for its aggressive nuclear power program and they have derived upwards of 75% of their utility

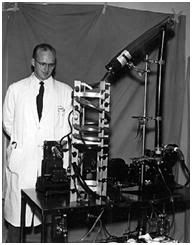

C. Walton Lillehei and his beer tubing and industrial finger pump heart-lung machine.

C. Walton Lillehei and his beer tubing and industrial finger pump heart-lung machine.

Nowhere have psychosocial factors been more of a problem in slowing technological progress than has been the case in the life sciences. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, a few daring surgeons in the US made the decision to develop cardiac surgery. A necessary element of such an undertaking was the development of the heart-lung machine to pinch hit for the patient’s heart and lungs during while the heart was being operated upon. The first such heart-lung machines were fabricated from industrial items, such as finger pumps and plastic PVC tubing used in the beer making industry.23 The DeWall-Lillehei oxygenator was just such a device – it was tested in dogs and then more or less immediately applied to humans. Twenty years earlier Willem Kolff had done exactly the same sort of thing with the artificial kidney machine – using an automotive fuel pump and sausage casing tubing to cleanse the blood of patients with acute kidney failure.24 Such rapid and direct application of biomedical advances to humans is now inconceivable, not only in the US, but virtually anywhere in the world.25,26

Research into stem cell therapies, cloning, and gene therapy technology have also been greatly slowed by psychosocial concerns. Clinical progress in these areas is a mere shadow of what it could have been, and arguably should have been, absent the widespread resistance on the part of a broad cross section of the public on moral and ethical grounds – grounds which have no basis in any rational framework of risks versus benefits evaluations. One can only wonder what the rate of progress in the life sciences would have been like had there been no Asilomar Conference and the creative energies of the brightest young minds in the West had been applied to engineering biology with even a fraction of the focus and vigor that engineering in computing and microelectronics have been pursued.

The enabling technologies that will be required for vast life span extension, recovery of cryopreserved patients, space colonization, and personal biophysical redesign and transformation are unarguably many times more mischievous and dangerous than was (or is) nuclear energy. Mature genetic engineering, nanotechnology, strong artificial intelligence, and quantum computing, to name but a few, each hold many times the potential for systemic harm to, or destruction of our civilization; and they do so absent the inherent check on their proliferation that was present in the case of nuclear energy, by virtue of the extreme scarcity of the necessary isotopes, and the even rarer and more exotic expertise and massively expensive hardware required to transform them into weapons grade materials. A likely consequence of this will be that the cost of these technologies will be much higher than anticipated and their development will also likely be slowed, as well as being rendered unpredictable and erratic.

Apocalypse Soon?

We must also confront the possibility that the civilization we are embedded in will, just as have all those that have come before it, fail and fail catastrophically. The very technology cryonicists venerate offers not only the prospect of immortality, but also of oblivion. History has been defined in many ways, but perhaps one of the best and most applicable here is that, “history is that period of time which has passed out of living memory.” To achieve practical biological immortality is, then, by that definition, to put an end to history. If we want to end history, then we must come to understand that where our personal survival is concerned, historical trends, and even historical certainties, will have no relevance if they do not occur in time to save our lives.

We must also confront the possibility that the civilization we are embedded in will, just as have all those that have come before it, fail and fail catastrophically. The very technology cryonicists venerate offers not only the prospect of immortality, but also of oblivion. History has been defined in many ways, but perhaps one of the best and most applicable here is that, “history is that period of time which has passed out of living memory.” To achieve practical biological immortality is, then, by that definition, to put an end to history. If we want to end history, then we must come to understand that where our personal survival is concerned, historical trends, and even historical certainties, will have no relevance if they do not occur in time to save our lives.

Finally, any study of history from a cryonics perspective leads to the inevitable conclusion that civilizations rise and fall based upon their core values, their commitment to the long-term versus the short-term, and of course, upon factors beyond their control, such as climate change, epidemic disease and military conquest.14 Cryonicists and Transhumanists must come to realize that in order to control history, and thus their own destinies, they must leverage their way into a position of control over the ideology, morality and direction of this civilization. To fail to do so at this juncture in time is to accede to the end of our history – not by the practical abolition of death, but rather by its universal application to humankind, and perhaps to all life on earth.

References

1) Nicholl, C. Leonardo da Vinci: Flights of the Mind. Viking Penguin, (2004). ISBN 0670033456.

2) Leacroft, R. The Buildings of Ancient Rome, Brockhampton Press, (1969). ASIN: B000Z4DOUO.

3) de Solla Price, D. An Ancient Greek Computer, Scientific American. June 1959 pp. 60-67.

4) de Solla, D. Price, D. Gears from the Greeks – The Antikythera Mechanism, A Calendar Computer from ca. 80 B.C., Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 64, part 7 1974.

5) Freeth,T, Jones, A, Steele, JM, Bitsakis Y. Calendars with Olympiad display and eclipse prediction on the Antikythera Mechanism. Nature. 2008;(454):614-617.

6) Gillispie, C. The Montgolfier brothers and the invention of aviation 1783-1784. Princeton University Press, (1983).

7) Gillispie, C. The Montgolfier brothers and the invention of aviation 1783-1784. Princeton University Press, (1983).

8) Boas, M. Hero’s pneumatica: a study of its transmission and influence,” Isis. 40(1);1949: p. 38 and supra

9) Archimedes Homepage: http://www.cs.drexel.edu/~crorres/Archimedes/contents.html.

10) Neufeld, MJ. The Rocket and the Reich: Peenemünde and the Coming of the Ballistic Missile Era. Harvard University Press, (1996). ISBN-10: 067477650X. Jaroff, Leon (2002-03-26). ‘The Rocket Man’s Dark Side.’ Time. onhttp://www.time.com/time/columnist/jaroff/article/0,9565,220201,00.html Retrieved: 05-23-2009.

11) Das Marsprojekt; Werner von Braun, Studie einer interplanetrischen Expedition. Sonderheft der ZeitschriftWeltraumfahrt. Frankfurt: Umschau Verlag 1952; English language edition: Werner vonBraun with Henry J. White, translator The Mars Project, Urbana, University of Illinois Press, (1953).

12) von Braun, W. The Collier’s Space Flight Series:

March 22, 1952: Man Will Conquer Space Soon, a collection of eight articles .

October 18, 1952: Man on the Moon, The Journey, and Inside the Moon Ship

October 25, 1952: Man on the Moon, Inside the Lunar Base

February 28, 1953: World’s First Space Suit

March 7, 1953: Testing the Men in Space

March 14, 1953: How Man Will Meet Emergency in Space

June 27, 1953: Baby Space Station

April 30, 1954: Can We Get to Mars? and Is There Life on Mars

13) Bhardwaj, RA, Curtis ,MA, Spalding , KA, et al. Neocortical neurogenesis in humans is restricted to development. PNAS. 2006;103(33):12564-12568: http://www.pnas.org/content/103/33/12564.full.

14) Mangano, JJ, Sherman, JD. Elevated In Vivo Strontium-90 From Nuclear Weapons Test Fallout Among Cancer Decedents: A Case-control Study Of Deciduous Teeth. International Journal of Health Science. 2011;41(1):137-158.

15) Too cheap to meter: the great nuclear quote debate: http://www.thisdayinquotes.com/2009/09/too-cheap-to-meter-nuclear-quote-debate.html.

16) “Ford’s mid-century concept cars forecast future vehicles”. Ford Media. http://media.ford.com/article_display.cfm?article_id=3359. Retrieved 8 Jan 2011.

17) Smyth NP, Millette ML. The isotopic cardiac pacer: a ten-year experience. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1984;7(1):82-9.

18) Kallfelz FA, Comar CL, Casarett AP, and Craig PH. Radiobiological Effects of Simulated Nuclear Power Sources for Artificial Hearts: A Preliminary Report

Transactions of the American Nuclear Society 1970;13 (2):499.

19) Alimov, R. Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators, Bellonas Working Paper, 01/04-2005: http://www.bellona.no/bellona.org/english_import_area/international/russia/navy/northern_fleet/incidents/37598.

21) EdF, Nov 1996, Review of the French Nuclear Power Programme, EdF: http://france.edf.com/-45634.html and http://www.world-nuclear.org/info/inf40.html.

22) Miller, W. King of Hearts: The True Story of the Maverick Who Pioneered Open Heart Surgery. Three Rivers Press; 2nd edition (2000). ISBN-10: 0609807242.

23) Cameron, JS. A History of Dialysis. Oxford University Press, (2002). ISBN: 0198515472.

24) Higgs, R. Wrecking ball: FDA regulation of medical devices. Cato Policy Analysis #235. August 7, 1995. http://www.cato.org/pubs/pas/pa-235.html. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

25) DiMasi, JA, et al. The price of innovation: new estimates of drug development costs. Journal of Health Economics. 2003;(22):151–185. http://cryoeuro.eu:8080/download/attachments/425990/CostOfNewDrugDevelop2003.pdf. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

26) Diamond J. Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. Viking Adult, (2004). ISBN 1-586-63863-7.

Notes

It would be difficult to find a better example than Wernher von Braun of the impact of a civilization’s choices on the moral behavior of an individual. Von Braun repeatedly visited the Dora-Mittelwerk facility in the Harz Mountains near Nordhausen, where concentration camp laborers were forced to assemble V-2s under deplorable conditions that resulted in staggering mortality.(1) It has been estimated that ~20,000 workers died in V-2 production, as contrasted with the comparatively miniscule 2,541 (documented) people who died from the use of the V-2 as a weapon during the war.(2) Von Braun acknowledged, in writing, that he personally selected workers for Mittelwerk from camp inmates at Buchenwald, who he described as in ‘pitiful shape,’ and he acknowledged that by 1944 he was aware that many of the slave laborers at Mittelwerk had been executed, that many others had succumbed to malnourishment and dysentery, and that the environment at Mittelwerk was “repulsive.”(3) Under the strict definition of the term, von Braun was not a war criminal, per se, (4) but it is hard to argue that he was not a party to ‘crimes against humanity’ as defined today by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court Explanatory Memorandum. (5)

After immigrating to the US under the auspices of Operation Paperclip, von Braun became a US citizen and led a life that might best be described as mirroring the morality of his new masters. Aside from modest amounts of work on the exploitation of space as a (thermonuclear) weapons delivery platform, the vast body of his career was focused on efforts to colonize space. (6) Arguably, not unlike most men (consider the Milgram Experiment) von Braun was a moral chameleon who behaved as was needed to advance his own interests and survival; in his case the conquest of space. While there is evidence that he was not indifferent to the human suffering and murderous exploitation he observed at Mittelwerk (7), there is even more evidence that he was unwilling to take any action, direct or indirect, to change the status quo, or even to withdraw from participation in the Nazi rocket development program (incapacitating illness is always a viable excuse).

Throughout his long career his only recorded incidents of insubordination or disobedience to orders are those that occurred when the interests of his prime directive, the exploration of space, conflicted with those of his masters. Notable examples are his disobedience of direct orders to destroy remaining V-2s as well as all drawings and documentation pertaining to the German rocketry program in the closing days of WWII, his forging of (contrary) orders to move him and his team into Allied hands (8), and his collaboration with Army General John Medaris who headed the US Army Ballistic Missile Agency in Huntsville, AL (again in direct violation of orders) to assemble and secrete a Redstone launch vehicle and its satellite payload (the Jupiter-C, a modified Redstone intercontinental ballistic missile that launched America’s first satellite, the Explorer probe) in anticipation of the failure of the US Vanguard effort to orbit an ‘artificial moon.’(9) In short, he appears to have been committed to the realization of space flight at any cost. This may rightly be considered as unforgiveable, but it should be remembered that countless others in human history have participated in such atrocities with nothing more grandiose at stake than the prospect of a better job, a little more money, higher standing in the community, or simply because they enjoyed the power and authority that accompanied their execrably inhumane jobs. Had humanity chosen to pursue space flight, instead of war and genocide, von Braun would almost certainly have been the man for the job; and a model citizen and untarnished hero in the bargain.

References for Notes

1) Jaroff, Leon (2002-03-26). ‘The Rocket Man’s Dark Side.’ Time. onhttp://www.time.com/time/columnist/jaroff/article/0,9565,220201,00.html Retrieved: 05-23-2009.

2) Neufeld, MJ. The Rocket and the Reich: Peenemünde and the Coming of the Ballistic Missile Era, The Free Press, (1995). ISBN-10: 067477650X

3) “Excerpts from “Power to Explore“”. MSFC History Office. NASA Marshall Space Flight Center. http://history.msfc.nasa.gov/vonbraun/excerpts.html. Retrieved: 05-23-2009.

4) Fourth Geneva Convention “relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War” (first adopted in 1949, based on parts of the 1907 Hague Convention IV)

5) Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, opened for signature 17 July 1998, [2002] ATS 15 (entered into force 1 July 2002), UN Doc A/CONF 183/9: <http://www.un.org/law/icc/statute/romefra.htm>

6) Neufeld, MJ. Von Braun: Dreamer of Space, Engineer of War, Alfred A. Knopf, (2007). ISBN 978-0-307-26292-9

7) ‘Biography of Wernher Von Braun.’ MSFC History Office. NASA Marshall Space Flight Center. http://history.msfc.nasa.gov/vonbraun/bio.html. http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Library/Giants/vonBraun/. Retrieved: 05-23-2009.

8) Cadbury, Deborah (2005). “Space Race,” BBC Worldwide Limited. ISBN 0-00-721299-2.

9) Brzezinski, M. Red Moon Rising: Sputnik and the Hidden Rivalries that Ignited the Space Age, Times Books, (2007). ISBN-10: 080508858X

[1] 288 billion 1945 US dollars in 2000 US dollars = 5 trillion dollars

[2] I include the Korean and Viet Nam wars, as well as other related conflicts as part of the Cold War.

[3] The devices were to be removed upon the death of the patient and returned to Los Alamos Laboratories for safe disposal of the plutonium power source. However some are unaccounted for and were interred or cremated with the patient they were implanted in.

I suspect that traditional theism plays a role in interfering with progress in biotechnology. Many theists believe that a god created life, so they call human efforts to re-engineer life “playing god.”

By contrast, no theist ever thought of attributing to his god the ability to create a computer, so theists leave computer engineering and software development alone.

I get the impression that Eastern cultures, which have developed independently from the influence of West Eurasian theism, seem less inclined to display these sorts of taboos about biotechnology.

What the author does not discuss is that much of the technological and scientific advances are due to the adoption of a system of approaching problems through the scientific method. This power philosophical and practical approach is fundamental to all modern research and is what sets apart the organized, systemic and ongoing advances we see in modern times against the halting ebb and flow of advances in previous eras of human history.

The article does highlight that technological advances are not always in lockstep with scientific knowledge due to economics and cultural concerns. Hence the need for cryonicists to find ways to push both the technological, and scientific, edge.

I like your analysis on von Braun at the end. It is often forgotten how welcome a lot of the scientists and results were in the US, despite the atrocities committed.

Scientists are no better off today. If anything, the lies have been institutionalized. The shining examples of freedom and democracy are the top weapon exporters of the world, researching remote mass-scale biometric identification, drones and ‘crowd control’. If you don’t like it, of course, you can always go into fund raising..

You have no idea! Maybe sometime I’ll write up the story of my encounter with DARPA, many moons ago, when I was younger and more foolish than I am now. — Mike Darwin

Via a HackerNews discussion: this brings me to think how easy duplication of clay tablets bearing cuneiform would be – impress a fired/set tablet on to a piece of wet clay, set that as the master and then potato print with that in to fresh clay pieces. It couldn’t really be simpler than that – why didn’t the Sumerians have printing presses in 4000BC?

Very interesting article.

It would be nice though if the author also commented on the topic of technological singularity, in the same context.

Your wish is my command: “I don’t believe in the technological singularity a la Kurzweil, et al.” — Mike Darwin

I liked the article a great deal but there is a miss of the fundamental cause and push that separates us from previous “peaks”, the network effect. Good ideas are no longer to be isolated in passing as a person toils away in obscurity. We are approaching a connectivity among peoples that is quite simply unimaginable, the emergent behaviours that will come from this will seem “duh!” afterwards, but right now, none of us have a clue what they will be.

Well, don’t be so sure about that. I’m saving it for later discussion, but there is a “bite-back” effect to the connectivity, and to the technologies which enable it. It’s subtle but powerful, and you can see it at work in areas like new drug and medical device development, where progress is actually slowing (dramatically), and not just due to regulatory burden. I want to be clear that I do agree that increased connectivity is transformative and powerful, but there are other really nasty factors in play, that I believe are going to really slow things down in areas critical to life span extension. — Mike Darwin

“…new drug and medical device development, where progress is actually slowing (dramatically), and not just due to regulatory burden.”

You’re right, it’s not due to regulatory burden; it’s due to little more than funding (lack thereof).

A thoughtful and provocative piece; I am interested in many of the same questions, which is why I’ve been writing my senior thesis on the subject. In a few months I’ll have more to share, to the tune of a hundred pages or so…

The question I’m exploring is one of “technological determinism and progress” or, more generally, understanding the roots of the ideas of progress held by transhumanists and others. In my opinion, these are just derivations of the enlightenment ideal of progress, an animating axiom of history which fell apart in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The question I’m trying to answer is “why” (analytically) and what if any components of such progress can be salvaged.

The degeneration of “progress” as driven by reason into “progress” as driven by technology, IMO, led to a fatal intellectual shift in which technology became confused as a means *and* an end. In that context, technology is pursued as an end unto itself, ignoring any other implications… among other consequences.

But, certainly a very interesting subject – enjoyed reading your take!

Interesting article! I recommend reading Basallas the Evolution of Technology for a detailed (and well written) thesis on how technology evolves and why certain societies (such as the romans or japanese) don’t adopt seemingly obvious choices (such as steam power and gunpowder respectively).

I just ordered it on Amazon for $6.00, It looks like a good read – thanks for the tip!

Werner Von Braun was a typical German. Once he set his mind on his vision and goal (space exploration), all other considerations became superfluous.

Nuclear power is making a major comeback, in Asia. Both the Japanese and Chinese are now pursuing the development of Thorium-based nuclear power as well as other Gen IV concepts of nuclear power such as the IFR. The LFTR (liquid-fueled Thorium reactor) is another concept that is being pursued. The Chinese, South Koreans, and Japanese are all developing complete nuclear power industry. It is also worth noting that of the two U.S. nuclear power players, Westinghouse is now owned by Toshiba and that GE’s nuclear power division is partly owned by Hitachi.

Nuclear processes are orders of magnitude more efficient for generating power than chemical processes. Despite all of the hoohaa over solar, wind, and other “renewable” energy concepts, the reality is that nuclear (fission or fusion) is the only game in town, in terms of energy generation. There is no other option.

http://www.lewrockwell.com/orig9/hogan3.1.1.html

Thanks for these comments – they are all true. But please, don’t forget about South Africa! They have put a lot of time and energy (with good results) into pebble bed reactor technology, which has the advantage (and disadvantage) of requiring very little protective infrastructure and of being scalable to the application – very small reactors are practical using this technology.

As to fossil fuels, sure, they are dinosaurs and can’t be relied on into any sustainable future. However, that wasn’t the case in 1973, and I believe that the powers that be at the time must have known of, and done thorough explorations of the Fischer-Tropsch process as it might have then been applied to the US oil situation. The reason I believe this is, because I was 18 at the time, and when the Arab oil embargo was seriously underway, I thought of using this technology as the logical alternative to being dictated to by people whom I found creepy, even then. I’m no genius and I was a teenager at the time. So, if I could think of this option, surely the petro-moguls and the politicians must have done the same. At that time there were still many in and around government who knew what had been done with FT during WWII, and knew what was even then going on with Sassol in South Africa. I have vivid memories of being stuck in Cumberland, Maryland with a cryopatient on dry ice, and not being able to get either auto or aviation petrol. I was furious, and just about all I could think of were the words Fischer-Tropsch.

They didn’t act to do the “right” thing because it would have been very painful economically at an already bad time, because men like Nixon and Kissinger probably lacked the capability and the inclination to even think in that way, because it was so much more profitable politically to continue to build a US “sphere of influence” in the Middle East (vis a vis the Cold War), and so on.

So what I’m really saying here is that the values of the people running he society were corrupt and counter to the long term interests and well being of the people they represented and governed. That stinks. — Mike Darwin

Re-reading this article; I couldn’t help but chuckle at this comment.

A 40-year limit on existing nuclear plants in Japan, and a commitment to derive no energy from nuclear power by the time the 2030′s are out (a position that enjoys popular consensus).

“There is no other option.”

When it comes to the future, there are ALWAYS other options, including (perhaps especially) those that seem unlikely *merely* because they aren’t optimal.

“Technological inevitability” …indeed.

Coal gasification Fischer-Tropsch process is cost competitive at around $100/barrel, in today’s money. Oil prices never got high enough in the 1970′s to justify coal gasification. Also remember the federal government mandated a price ceiling on all domestically produced oil during the 1970′s. This price ceiling made it impossible for domestic energy reserves to be developed, including coal gasification. Removal of this price ceiling was Reagan’s first act as president, the first day he was in office.

The oil shale and tar sands in Northern U.S. and Canada are cheaper to extract than Fischer-Tropsch process. The tar sands fields in Alberta are starting to come on line. Also, the U.S. has lots of natural gas in the form of shale gas. You also have to dealize that the industry suffered a serious crash in the 80′s when oil prices declined (and anyone who was leveraged in the oil industry promptly went bankrupt). The oil industry is full of guys in their 50′s and 60′s who remember this crash because they have not hired anyone in the past 30 years. They want to be sure that oil prices will remain sustainably high before they will commit billions in financing to developing non-conventional sources of hydrocarbons such as tar sands or coal gasification. They got burned once, they don’t want to get burned again.

Pebble-bed reactors have several limitations that other designs do not have. They do not allow for easy reprocessing of the nuclear fuel. However, this limitation can be overcome by deep burn-up (50% or more) of the nuclear fuel. Conventional reactors have only about a 7% burn-up of the nuclear fuel.

More on nuclear power:

http://energyfromthorium.com/

My favorite blogger have lots on nuclear power:

http://nextbigfuture.com/search/label/nuclear

There are lots of concepts for small nuclear power plants.

As you can guess, I’m a big-time advocate of nuclear power. I think the LFTR concept is the best for fission nuclear power.

There are four non-conventional approaches to fusion power that are being pursued by private groups. If we’re lucky, one or more of these will work out:

1) Tri-Alpha Energy – a variant of FRC (funded by Paul Allen and others)

2) EMC2 – Bussard’s Polywell IEC concept (being funded by the Navy)

3) Focus Fusion – this is Eric Lerner’s DPF

4) General Fusion – I call this steampunk fusion

Nixon and his buddies were definitely criminals. They are to blame for the stagflation of the 70′s. Nixon appointed one of his cronies as FED chairman, who proceeded to keep interest rates low despite Nixon’s keynesian fiscal policy. The stagflation of the 70′s was a result of this.

No serious disagreement with anything you’ve said. My point remains, however, that regardless of the economics, it was a BAD decision to cave to the embargo and put the national security of the US and the immediate well being of its citizens in the hands of people who are the very working definition of short-sighted corruption, and who spend much of their waking time bleating “Balsheesh, baksheesh, baksheesh…” The South Africans were willing to make an even larger and more painful sacrifice just to preserve their racism. Long term vs. short term thinking. And yes, Nixon was a crook… –Mike Darwin

“To fail to do so at this juncture in time is to accede to the end of our history – not by the practical abolition of death, but rather by its universal application to humankind, and perhaps to all life on earth.”

Hyperbole. We would find it impossible to extinguish all life on Earth. Life is much too hardy, varied, and adaptable.

Just wait, if we crack quantum computing, you haven’t seen anything yet. This kind of progress tends to scale at least exponentially, which means that soon enough (and probably too soon) the hydrogen bomb may seem like nothing more than a firecracker. — Mike Darwin

To be honest, I’m not impressed with quantum computing.

Quantum computing can do certain calculations that convention computing does not. However, it cannot be used as an all-purpose replacement for conventional computers. Also, the kinds of calculations that quantum computers will be able to do have application in certain lines of research, in particular modeling, but not in others.

I feel the same way about A.I. as well. First, I don’t expect sentient A.I. in the foreseeable future mainly for the reasons you cited in your discussion of neurobiology in this blog. Brains really are different than computers and I think it will be very difficult to emulate brains using computers, either digital or quantum. Thomas Donaldson used to talk about neurobiology and the reasons why it is difficult to emulate in computers. Also, once A.I. is developed, I’m not certain it will have that big of impact. Having sentient A.I. is no different than having a bunch of bright guys in a room. Technological innovation is limited more by the availability of finance and the rate of physical experimentation, not by the number of bright people.

Perhaps a sentient A.I. will have an human IQ equivalent of 500 and will, therefor, be able to develop the quantum gravity theory that will allow for FTL or wormholes. One can always hope (this actually is the wild card).

The technologies that offer real changes during this century are mainly bioengineering (biotechnology, synthetic biology, “wet” nanotechnology) and possibly fusion power (see my earlier posting). I’m even skeptical of the possibility of “dry” or nano-mechanical nanotechnology. An excellent book that discusses the fundamentals of nanotechnology is Richard Jones’s book “Soft Machines”.

http://www.amazon.com/Soft-Machines-Nanotechnology-Richard-Jones/dp/0199226628

Jones’ argument is that complex nanotechnology will necessarily be soft and squishy because of Brownian motion. I think he’s correct. Again Thomas Donaldson used to talk about this as well. It is unfortunate that he got cancer and had to go into cryo-preservation. This is definitely the century of biology.

Semiconductor scaling will reach the molecular level in the next 20-30 years, which will probably represent the limits of computation. I think technology in all other fields will continue to improve in an incremental rather than revolutionary fashion.

Doesn’t Brownian motion only exist at relatively high temperatures? I can see this as a limitation for warm bio-friendly temperatures, but for cryonics purposes you could even use machines that require a vacuum, or exposed surface areas to work with.

Yes. All of the “nano-mechanical” stuff developed to date works only at cryogenic temperatures. All room-temperature stuff being developed is “wet”. Some of it is becoming impressive.

Many wonder why didn’t the ancient Greeks or Romans, or any other advanced ancient culture, have an industrial revolution when they had all the necessary components? The answer is simple, slavery. The ancient Greeks and Romans had advanced mathematics and an understanding of machinery, so why were ancient inventors basically inventing curiosities and not industrializing? You just couldn’t match what a human could do and slaves were cheap and abundant. It’s no coincidence that the industrial revolution in the western world came about around the same time slavery was beginning to be outlawed.

Well, I can tell that you work for people, and that people don’t work for you ;-). People are a pain in the ass, even when you pay them well, and treat them nicely. They are dangerous and troublesome out of measure if you enslave them. And they are not cheap. They are never, never cheap. Slaves have always cost a fortune. To add insult to injury, slaves do a lousy job, and they are, almost without exception, usable mostly for brute and unsubtle labor. The Roman’s used machinery – heavy duty complex machinery, whenever they could. The Egyptians used well paid, skilled workers to build the pyramids and excavate the tombs in Luxor. If you ever get to Egypt (and if it’s still there), see Deir el-Medina – the workers lived well.

Today, every businessman worth his salt replaces humans with machines at the first opportunity, whilst shouting, as any good Roman citizen would have, “Gratitude! Gratitude!” –Mike Darwin

Having run a business, I can tell you this is certainly true. I dislike managing and working with non-technical people. Talk to anyone who has ever owned a store, coffee shop, or a contracting business and they will tell you the same thing.

The one exception to this rule are engineers and scientists as well as Japanese and German people.

Countries with declining population (Japan, Germany) are big into robotics and automation.

Oh, I could tell you stories about the stupidity I have to deal with from the public. It just amazes me how many people have literally no savings, yet they want to spend their next paychecks on a “romantic getaway.” So they try to talk me into holding cabins for them with their debit cards, even though they’ve just admitted that their checking accounts don’t even have $100 in them.

Actually, this is pretty rational behavior, given the context of the times. First of all, they are going to die very soon, even if its 40 years in the future, and they know it. Granted, they don’t know it like you and I do, but they do know it. And by the time they are in the 40s or 50s, they are really beginning to know it. In non-cryonicists, the denial mechanism is fantastically effective, but it still has chinks in it. Add to that the understanding that there is a “floor” on how bad things can get for you in old age in a Developed World nation-state, and why NOT go for the gusto, while you can? What I find grimly fascinating at this age in my life is to see what the quality of life is really like for a fairly large fraction of the population in old age (65 and over; the formal definition of old age). It isn’t terrible, but it isn’t good, either. In the past, most people didn’t have the option to “live it up” while they were young and at other peoples’ expense. That’s probably just as well, given that it makes a lot more sense, even by rigorous mathematical analysis, than scrimping and saving for old age.

Charlie Sheen is unarguably “crazy” (Bipolar Type I, IMHO, if I’ve ever seen one), but there is great truth to his ravings. He has been places, seen and done things that feel so good, the average man would break down and weep with regret, if he knew what he had missed. And since he knows he’s going to die, the question is, how much quantity do you want to trade off for quality? Most people don’t get that choice ;-0. Again, that’s probably just as well. — Mike Darwin

There may be more to the slave thing than you think.

For perspective sake: There was a Roman vase in the British museum that was identified as a depiction of a charnel house, where human bodies were being systematically dismembered. And so it stayed, for about a century, until the paradigm of interchangable parts and assembly lines had been “discovered”. It’s a depiction of a statue factory. And statues have been found that can now be identified as being cast in pieces production-line fashion.

Next: First Americans (a.k.a “Native Americans” or “Indians”) were identified by Europeans as having a minimal level of technology. No appreciable use of metal, no tall buildings, no gunpowder. Primitive. Six hundred years later we are now discovering bio-engineering. And DNA analysis finally lets us appreciate the work that went into engineering corn, as well as other biological artifacts.

So. The Romans had slaves (not just brute labor, also highly skilled). And they made that work for hundreds upon hundreds of years (despite a few radical foreign groups that claimed an eye was worth an eye regardless of who it came from). How did they make it work, when every person posting here has complained about their employees? In modern times we have theories of “attitude change” and “neuro-linguistic programming” and other forms of psychological manipulation. How primitive are these compared to Rome and Egypt?

And, if they could make the slave thing work, why would they bother inventing the dishwasher? (And what are we not bothering to invent?)

OK, those are good arguments – and were exactly what I was looking for! When I wrote about “technological inevitability” in cryonics, I was writing to make the point that there is, in fact, nothing inevitable about it! I chose von Braun as an example with great care. Here was a man who wanted to do an eminently technologically feasible thing: go into space personally, and make our species a spacefaring one. And he was willing to do absolutely anything required to achieve those ends. Planet-wide warfare? No problem! Concentration camps filled with starving and brutalized innocents to build his rockets? No problem! And yes, he failed. He did so for many reasons, but in large measure because he failed to change the core values of the culture. The resources to allow humans to become a spacefaring species were readily available – as available as canvas and of hot air were to the Romans (who had plenty of both). But “we” chose not to go into space as a people because “we” didn’t want to do it. Instead we spent many, many times the amount required in blood and treasure on other things.

Are we, as another poster here, Bill Swallow, asks (and thus points out), missing core, fundamental insights into how the universe works because we are “blind” to them? Blind to them for many of the reasons you so well call out in your post? Absolutely; it would be a miracle were it otherwise!

But here is the really critical point, and it is a bloody well important one, we do know what kinds of technologies are necessary to achieve practical immortality for most of us now living. And, if we can shepherd those technologies into existence, and do so without our self destruction, then we will have all the time in the world (and lots more besides) to uncover all of the workings of the universe. We can sit and wonder with our tiny minds what we might have missed, or indeed what we must have missed, or we can reach out, grab the low hanging fruit of practical immortality, gorge on it, and go and see for ourselves.

What we must not do, is to make the mistake of assuming that those enabling technologies are “inevitable,” that they will just pop into being, or continue incubating in the cultural womb, like an embryo to be born at some almost precisely specified calendar date in the future, because that may not happen, or it may not happen time. That’s the lesson of history, and few illustrate it better than von Braun. If you read his primary writings, you realize almost at once that he thought that once manned spaceflight was achieved, human exploration and exploitation of space were inevitable. They weren’t.

Inherent in cryonics is the assumption that the future will get better and better, not just in general, but in highly specific ways. The cryonicists who do this assume/extrapolate based on their own values, which they mistakenly assume are shared by the culture, and by the civilization which they inhabit. This is the von Braun error and it is deadly dangerous. That assumption cannot be made, and if you go to any entity: NGO, nation-state, for profit corporation, and hand them your technology, and then expect them to exploit it to embody your values, let alone your dreams, well, then you are at best naive, and at worst you are an idiot. That was my point.

Finally, and tangentially, regarding the Native Americans. I strongly recommend Stephen Ambrose’s “Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors.” I think his analysis of Amerindian culture has much to say about the long term future of humans – if we achieve practical immortality. One of the things Ambrose points out was that the Amerindians were fundamentally unable to grasp the idea of command and control structures. They did not have employers or employees, and because they used population control, and lived a (“low”) technical-hunter-gatherer lifestyle, and to a lesser extent an agricultural one, they did not need a highly organized hierarchical social system – in fact, they couldn’t even understand it. The idea of one man ordering another man to do something, and him subsequently and unquestioningly complying, was completely alien to their experience. This put them at a terrible military disadvantage. It was a gulf in understanding as great as that between the Romans and us over the issue of autonomy in slavery. From the Roman perspective, a slave was perfectly free, because he could choose to end his slavery at any time, by taking his own life. Indeed, we see Cicero, magnificent intellect that he was, presenting his shoulder to the soldier who was to run him through, with the admonition that the man “do a good a job.” — Mike Darwin

What you mean “we” Kemosabe?

Touche’. –Mike Darwin

Thank you, ringo. I love the people that I am meeting here.

If this means “history matters”, well, yes! But had there been no WWII and no Cold War, no one would have given lots of resources to allow Wern to develop his ideas into things! Depending on the causes for an absence of the wars, the world’s people might be better off, or worse off, than in reality, with or without Wern’s toys.

The most crucial technology I can think of is the flush toilet.

We do not control our destiny, and never will.

WWII was caused by how WWI ended. It was the Treaty of Versailles that ultimately resulted in the rise of Nazism and WWII. WWI was a stupid European tribal conflict that was not based on any substantive issue. It was one of the stupidest, most pointless wars in human history where the European nations blew away 2/3 of their economic assets for nothing at all.

I don’t even know why we got into it except that Woodrow Wilson was an asshole.

Barbara Tuchman was a far leftist historian and writer. By all reason and common sense, what she had to say about history should have been impossibly warped. But this was not the case, in fact, I believe she has one of the clearest and most unbiased views of history as does any 20th century historian. When I was maybe 15 years old, Curtis Henderson literally tossed a stack of books at me and said,”Here, read these, or you’ll go through the rest of your life as ignorant and clueless about how the world really works, as you are now. Two of the books in that stack were the Zimmerman Telegram and The Guns of August. The Guns of August had a strong effect on me, and while I didn’t know it at the time, it may have contributed to saving my life (and yours too) because President Kennedy was powerfully influenced by the book, and he distributed it widely to his cabinet, national security apparatus and to his generals and commanders, and ordered that they read it, during the build up of the Cuban Missle Crisis. The book is Tuchman’s analysis of the foolishness that lead up to WWI. On my second or third visit to CSNY, I had a book to thrust into Curtis’ hands, Tuchman’s A Distant Mirror, which is an analysis of the 14th Century – and a brilliant one at that. But it was not until some years later, when I was trying to understand why colleague and mentor Jerry Leaf was being psychologically devastated by the things he had done while in the Phoenix Forces, in South and North Vietnam, that I turned to Tuchman’s The March of Folly. In my opinion, this is her magnum opus, because it seeks to, and largely does explain why powerful nation-states inevitably involve themselves in futile, and ultimately utterly calamitous foreign wars against insurgencies, in the mistaken belief they can protect their interests. It is a brilliant, a tour de force, and very depressing reading. Since then, I have read many brilliant books on the mechanics of the Vietnam conflict, and looked over many hundreds of documents and cables. Many of these books are beautifully crafted analyses of the minutiae of the decision making, and the political and economic influences that shaped Vietnam – but none comes close to Tuchman’s March Of Folly, in terms of making the historical framework, and the historical inevitability of such decisions so universal and inescapable. Kennedy was days or weeks at most from phasing out of Vietnam when he was killed. One can only wonder. — Mike Darwin

One wonders what similar breakthroughs are within our reach now, that we are inexplicably overlooking, and which might take decades, centuries, or more to realize. We are no more immune to this phenomenon than the ancient world was.

Mach-Lorentz thrusters?

Will you pardon my saying the theory behind Mach Thrusters is somewhat ridiculous? I hope so.

Theories abound, like lottery tickets. But most (lottery tickets) are ridiculous wastes of money. Ascribing hope to a ridiculous theory is like buying a lottery ticket that is stamped by the maker with “Nyahh, you aren’t going to win with this one, you dope!”

Allow me to diverge into mere rhetoric, please: The Mach Principle is like the Achilles And The Tortoise Paradox, it’s a rhetorically rich but practically implausible and rather muddled piece of ‘reasoning’. (Though annoyingly valuable in stimulating thinking, perhaps.) Does every object ‘observe’ the ‘frame of reference’? if one believes that, one must believe something like consciousness being inherent in all atoms and molecules… which does not explain why our fingernails do not make their objection to being trimmed known to us, when we trim them!

And temporary slight variations in mass – if not mere imperfections of the instruments of observation – are like the slight variations in the figures of the Rhine Experiments, and of as little probative significance or (especially) *usefulness*. Despite J.B. Rhine, nobody has developed practical telepathy etc. I dare to presume so.

Add to that the understanding that there is a “floor” on how bad things can get for you in old age in a Developed World nation-state.

Yeah, well some of us don’t expect that “floor” to last, life extension or no life extension. Have you seen the level of indebtedness that ALL developed world nation-states are in (especially Japan)?

I don’t expect it to last either. See my posts on “Universal Health Care” and “London at Apogee.” If the laws of thermodynamics are real, then the whole house of cards will come crashing down – and sooner, rather than later. HOWEVER, years of experience have taught me that when that will happen can be very hard to predict. One reason for this is that nation-states can steal – not just internally but externally, as well. My semi-communist Russian friends will be incensed at this remark, but the Soviet machine was powered for at least two generations in part by the confiscated labor, infrastructure, and to a lesser extent, the capital of their client states. Germany was more than bankrupt before WWII, and a significant part of its recapitalization was at the expense of the Jews and the absorption of the Balkans, and confiscation of their productive capacity. And lets not leave the British Empire out of this: the revenue stream from the various East India Company operations and their Colonial efforts was fantastic, and went for centuries. The US has been more “benign” in the human rights arena (overall) but it too, as an empire, has profited substantially, if less directly, from redistributed colonial wealth. If it chooses (along with Western Europe) to get really nasty about resource confiscation elsewhere, those folks who want that weekend getaway in Arizona on someone else’s dime, may indeed grow old and die and STILL be at it, when they go. It’s a strange, complicated world, and the longer I live in it, the more I find myself wondering if there isn’t the equivalent of a 12-year old gaming programmer giggling loudly somewhere, and living in fear of a good thrashing from from his uberminds when he gets caught. — Mike Darwin

At the risk of opening the gates of hell, Mike, what do you make of the view which attributes many of our social dysfunctions to feminism and “misandry”?

References:

http://www.singularity2050.com/2010/01/the-misandry-bubble.html

http://www.parapundit.com/archives/006761.html

The transhumanist manginas on the IEET.org blog like Hank “Hyena” Pellisier who support this feminist nonsense make my skin crawl.

In the wider socialist-feminist world, cognitive linguist George Lakoff tries to make the “strict father model” sound unappealing, but his characterization of the conservative world view makes certain aspects of conservatism sound more appealing to me, not less. We do live in the dangerous world assumed by the strict father model, and for the foreseeable future men have better equipment for dealing with it than women.

Again, this is an entire article. The issue is much deeper than the “feminazi” issue, per se. It also involves the fundamental developmental and cognitive differences between males and females – in humans and other mammals. If boys are mishandled during development, they end up emotionally and cognitively impaired. Of course, this is true for girls, as well, but it is only recently that any society or culture has tried to rear and educate males in the way it is now being done in much of the West. — Mike Darwin

If if if if if if if…

Entertaining read though.

Very interesting article and very well written!

A great deal of this short-termism of the free-market.

We can see this when we compare American and German capitalism. The German model of ‘social-capitalism’, based on good-industrial relations (tending not to sack r ‘n d and keeping experienced skilled staff), and long-term industrial investment produce higher quality and more technological advanced products; whilst American capitalism is essentially a race to the bottom, and outsourcing production and cutting r ‘n d is highly profitable to please fickle shareholders – it does over the long-term create industrial collapse and technological regression, as we can see in Seattle and Flint. Competition is good, but not if it means short-termism.

Pingback: Links van 8 juni 2011 tot 9 juni 2011 — Michel Vuijlsteke's Weblog

Pingback: Insaniquarium indeed! | Poison Your Mind

I think it this should be explored fully:

The Romans would have found no need for a train. I accept this fully, whether I was slave or emperor I would not have wanted a train. There a hundreds of reasons why I would have considered it a waste of time and energy. So then whatever changed our minds is the key question, not the train or any invention, but what changed us. How, why, when; was the change none of our doing? Forget the train, that will arrived anyway, what happened us is the fundamental question. And I think all real change might come against our wishes. So maybe, when life makes no sense is when we’re nearest to a new invention. The light at the end of the tunnel is that dam train again!