By Mike Darwin

Morals with an Expiration Date?

Forty-seven years ago, when cryonics was brand new, a nearly universally asked question was, “What if you are married and your wife dies and is frozen, and you subsequently remarry, and you and your second wife are frozen, as well. What happens when all of you are revived?!” This was a deadly serious question, asked with creased brows, and great concern. It wasn’t asked because people were trying to be snide or clever, but rather because it reflected a deep moral concern about the sanctity of marriage, which cryonics called into question at that time. Today, the only people in most of the Western world who are much exercised about marriage are homosexuals, who haven’t had an adequate taste of it, and polygamists, who would have no problem with being recovered from cryopreservation to find they had two wives – and who might well be disappointed that they didn’t have more. The mid-20th century angst about the revived cryonicist with two wives, as seen from the perspective of the early 21st century, seems quaint, and more than a little archaic.

Today, no one asks that question about cryonics, or raises it as a serious objection to the idea of medical time travel, in general. The reasons for this shift have profound implications for cryonics, and for cryonicists, implications that that will be explored here, directly.

Marriage as a Bellwether and an Example

Historically, whether monogamous or polygamous, marriage has been a bedrock social institution, because of its economic, and perceived eugenic functions. Since it also has historically constituted the fundamental functional unit of society, it has carried enormous political weight, as well. Because of the crucial importance of marriage to the social and economic order of society it has, universally, been considered too important to be left to the discretion of the young and inexperienced people who are going to engage in it at, or shortly after reaching reproductive age; and this meant that historically, in virtually all cultures, marriages were arranged, brokered, or otherwise largely determined by the society as a whole (via a multitude of proscriptions and regulations), and, of course, by the families of the bride and groom. Since marriage was a principal mechanism whereby wealth was consolidated or diluted, the economic incentives for control of it were extraordinarily powerful, even absent considerations of social standing, or ‘good breeding.’

The explosion of wealth, and the ability to become self-made, and experience vast social mobility in a single lifetime, are completely artifacts of the Industrial Revolution and rapidly advancing technology. When the resource pie was finite, careful attention to how it was divided up was essential to the survival of both families (as institutions), as well as to individuals who married.

Until the late 18th century, parents were in virtually complete control over whom their children wed, and they had the corollary power to dissolve marriages undertaken absent their approval. The quaint custom of the groom asking the bride’s father for his daughter’s hand in marriage, is a vestige of what was once a very serious and essential step in the process of achieving a durable legal union.

From a social perspective (again rooted in the conservation of wealth and status), the institution of marriage was also enforced through the status of children: a child born outside an approved marriage was a “fillius nullius” – a child of no one, entitled to nothing and what’s more, socially nothing. State enforced sanctions (not to mention social ones) against children born out of wedlock were powerful tools used to stabilize, and further the institution of marriage. A few blocks from my childhood home in Indianapolis, was a ‘home for unwed mothers.’ It was a multistory brick structure with wire grates on all of the windows in which “foolish and immoral girls” were incarcerated until they gave both birth – and their babies up for adoption.

From a social perspective (again rooted in the conservation of wealth and status), the institution of marriage was also enforced through the status of children: a child born outside an approved marriage was a “fillius nullius” – a child of no one, entitled to nothing and what’s more, socially nothing. State enforced sanctions (not to mention social ones) against children born out of wedlock were powerful tools used to stabilize, and further the institution of marriage. A few blocks from my childhood home in Indianapolis, was a ‘home for unwed mothers.’ It was a multistory brick structure with wire grates on all of the windows in which “foolish and immoral girls” were incarcerated until they gave both birth – and their babies up for adoption.

Well into the 19th century, European and American husbands had the right to physically imprison or punish their wives (and children). Again, as a child in a working class neighborhood, I can attest that wife beating was a commonplace that, while technically illegal, was mostly frowned upon, rather than prosecuted. Husbands had disproportionate control over the marital assets (as opposed to total control in the 19th century) and it was understood that children were to support their parents in their dotage.

The Advance of Technology and the Erosion of Traditional Marriage

The primary engine of change to the institution of marriage was technological advance and increased wealth. These decreased the pressure on both families and their children to both ‘marry well’ and to care for parents in their old age, because, for the first time in history, average people were increasingly able to both generate and retain enough wealth during their productive lifetimes to have saved enough to ‘retire on.’ Indeed, the whole idea of retirement is a direct product of the enormous wealth generated by technological advance, since at all prior times in human history the resource pool was always at, or near subsistence levels, and people worked until they could no longer do so, or they died. Prior to the 18th Century, the idea of healthy, potentially productive people no longer working, and consuming, rather than generating assets, would have been not only unthinkable, but morally repugnant, as well.

The Industrial Revolution changed that, and a consequence was that ideas such as love and intimacy began to become important to ‘courting’ couples and their families, and this was the first major destabilizing force to be brought to bear on marriage. Marriage thus increasingly became a negotiation between the would-be bride and groom, with the increasingly strong expectation that happiness should be an outcome, as well as economic and social well being, both for the married couple, and society.

Literally at the same time cryonics was being introduced as an idea, the birth control pill was introduced (1960). As is always the case with any fundamentally transformative technology, it would take (at a minimum) one human generation for the social effects to begin having a major impact – and this is precisely what happened in the case of ‘The Pill.’ Beginning in the mi-1970s, and continuing through the present, the pill, operating in concert with many other changes brought about by increasing wealth and rapidly growing demands for competent workers in all sectors of the economy (leading in part to the increased education and employment of women), dramatically eroded the stability of traditional marriage. An explosion of divorce, cohabitation, and the emergence of the gay rights movement were but a few of the results of these changes. There was also a large increase in the average age at which people marry; especially amongst the educated and affluent. At present, half of all Americans aged 25-29 are unmarried, and the idea of marriage as prerequisite for sexual activity, or long-term intimate relationships, is now almost passe. Currently, ~ 40 percent of children in the US and UK are born to unmarried parents, and homosexual unions, and even gay families with children, are both commonplace and widely tolerated, if not accepted. Certainly, it would be considered socially unacceptable to actively attack, or otherwise marginalize such families, even in fairly conservative parts of the US, and most other Western countries.

it would take (at a minimum) one human generation for the social effects to begin having a major impact – and this is precisely what happened in the case of ‘The Pill.’ Beginning in the mi-1970s, and continuing through the present, the pill, operating in concert with many other changes brought about by increasing wealth and rapidly growing demands for competent workers in all sectors of the economy (leading in part to the increased education and employment of women), dramatically eroded the stability of traditional marriage. An explosion of divorce, cohabitation, and the emergence of the gay rights movement were but a few of the results of these changes. There was also a large increase in the average age at which people marry; especially amongst the educated and affluent. At present, half of all Americans aged 25-29 are unmarried, and the idea of marriage as prerequisite for sexual activity, or long-term intimate relationships, is now almost passe. Currently, ~ 40 percent of children in the US and UK are born to unmarried parents, and homosexual unions, and even gay families with children, are both commonplace and widely tolerated, if not accepted. Certainly, it would be considered socially unacceptable to actively attack, or otherwise marginalize such families, even in fairly conservative parts of the US, and most other Western countries.

Defining Morality and Ethics

The word morality is derived from the Latin moralitas, which translates as “manner, character, or proper behavior” that differentiates intentions, decisions, and actions between those that are good = right, and bad = wrong. A moral code is a set of mandated behaviors that exists within an institutional or philosophical framework, and a moral is any given obligatory behavior within a moral code. Immorality is the active opposition to morality, while amorality is usually defined as unawareness of, indifference towards, or disbelief in given moral code.

Morality has two principal social definitions:

It may refer refers to personal or cultural values, codes of conduct, or social mores that distinguish between right and wrong in society. Defined in this way, morality is understood as not to be making any claims about what is objectively right or wrong, but rather to what is considered right or wrong by an individual, or some group of people, such as a religion or culture (contemporary secular Jews nicely exemplify the latter). This definition of morality might more properly be referred to as ‘descriptive ethics.’

The ‘normative’ definition of morality defines unequivocally, in absolute terms, what is right and wrong, regardless of what the individual thinks. This definition of morality is absolute, and is accompanied by ‘definitive’ statements such as, “That act is immoral” rather than descriptive ones, such as, “It is the opinion of many in the community that said act is immoral.” This ‘absolutist’ view of morality is challenged by moral nihilism, which rejects the existence of any moral truths, whilst the absolutist view is, conversely, supported by moral realism, which supports the existence of fixed and unchanging moral truths. Without venturing into complex areas of debate such as normative ethics, the definitions above will serve for what needs to be said here.

Donation After Cardiac Death (DCD): Another Example and Critical Bellwether for Cryonics

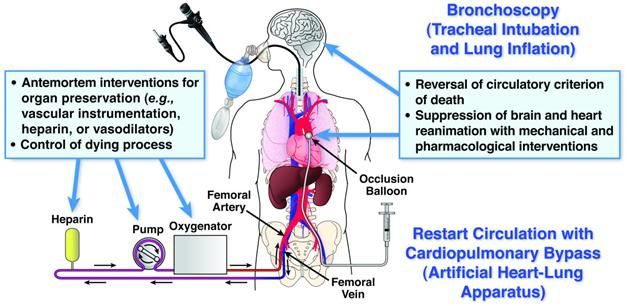

As is obvious in the discussion of marriage above, technological advance has rendered what were once considered formerly absolute and indisputable moral truths irrelevant, or at the very least, called them into question. This is analogous to what has happened with respect to the traditional medico-legal definition of death, and the resulting moral and ethical[1] chaos that has resulted. An excellent example is the fallout from the collision of the conventional (and incorrect) binary paradigm for defining life and death in medicine, with the reality of the information-theoretic paradigm, in the form of the current explosive debate over Donation after Cardiac Death (DCD). In brief, what DCD consists of is the retrieval of organs from people who are not brain dead, but who either cannot be resuscitated from cardiac arrest, or who choose not to be. One example would be the heart attack victim who receives prompt CPR, but whose heart cannot be re-started. In such cases, if CPR is continued until the patient can be connected to a cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) set-up, his organs may be retrieved for use in transplantation. [1,2] Similarly, an increasing number of patients on chronic ventilator support, or who have left ventricular assist devices (such as former Vice President Cheney now has), and who are not candidates for heart transplantation, may decide they have ‘had enough’ of such treatment, choose to withdraw from it, and want to donate their organs for transplantation.

Schematic of the procedure used in Donation after Cardiac Death (DCD): the procedure used precisely maps that developed by cryonicists decades ago to support post-pronouncement viability in cryopatients, with the notable exception that the brain is actively excluded from such support in DCD. [1]

The problem with this is that all of existing law was drafted around the assumption that only people who were brain dead would be candidates for organ retrieval. [3] The idea that people with potentially viable brains, let alone people who are fully conscious and medically stable whilst on life support being able to give organs (and their lives!), let alone choosing to do so, was inconceivable when the law was drafted nearly 40 years ago. Indeed, the law was put into place long before the Brother Fox and Karen Quinlan cases, amongst others, established the legal right of patients, or their surrogates, to forego life sustaining care. As a consequence, medicine is now being forced to confront the fact their definition of death is arbitrary, largely a function of technology, in no way absolute, and what’s worse; mostly comes down to a choice on the part of the patient as to when he decides he is dead, as opposed to when the physician decides he is dead. This is all very confusing, embarrassing and stressful for the still paternalistic (and often non-scientific) discipline that is medicine. [4,5,6]

DCD has lead to a fracture within the medical community [7,8] wherein some centers, such as the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, have taken patients who want ventilator support withdrawn, placed femoral cannulae under local (spinal) anesthesia, turned off the ventilator after effectively anesthetizing the patient, waited until the patient’s heart stops, and then restarted circulation with CPB. They also, of course, give paralytic neuromuscular blocking drugs (as is routine in all visceral organ retrieval) to prevent the thoracoabdominal incision, and the terminal drop in blood pressure (when the organs are removed), from causing muscle vesiculations (twitching) or actual limb movement as a result of stimulation of the nocioceptive pathways in the spinal cord (pain is a local phenomenon first and a central nervous system one secondly with the process proceeding up the spinal cord to the brain). [9,10]

To be blunt, this procedure resulted in all hell breaking out. [11,12,13] Bioethicists, such James Bernat and Leslie Whetstine, accused the surgeons and neurologists involved in this undertaking of every ethical evil, including homicide.[14,15] A compromise position is to restore circulation in the body using a special balloon-tipped aortic catheter that prevents ‘all ‘ flow to the brain. This results in a ‘resolution’ to the ‘paradox’ of removing organs from a patient with a ‘viable, or potentially viable brain.’ Of course, from our perspective as cryonicists, this whole exercise is nothing more or less than a procedural contortion designed to avoid confronting the reality that death is not a binary condition, and that if you are going to allow people to withdraw from medical care they no longer want, and that they (rightfully) consider an assault, then the corollary to that is that they also get to decide when they are dead. [16] That means that they have the perfect right to ask for, and receive a treatment (i.e., in the presence of informed consent) whereby they are anesthetized, cooled, subjected to blood washout, and their organs removed – at which point they are indeed DEAD, in the sense that their non-functional condition is now irreversible, or not going to be reversed, because they do not want it to be. When, exactly, they become irrecoverable from an information-theoretic standpoint is irrelevant, because they don’t want to be recovered, and no technology currently exists that will allow them to be recovered.

We, as cryonicists, could argue that if such patients were cryopreserved, they might possibly be recovered in the future. But if they do not want cryopreservation, then they are dead when they say they are dead, and when they meet the current medico-legal definition of cardiorespiratory death (i.e., no heartbeat or breathing and no prospect of their resuming). The medical response to this fairly straightforward situation has been, as expected, convoluted and irrational, and profoundly dangerous to cryonics. The recent paper “Clarifying the paradigm for the ethics of donation and transplantation: Was ‘dead’ really so clear before organ donation?” [17] is an excellent window into current medical policy, not just on the issue of DCD, but on the application of any kind of circulatory support to patients who have been pronounced dead on the basis of clinical (cardiac) criteria. This article is one of the most cited in current DCD debates, and the closing sentence in its abstract says it all (emphasis mine):

“Criticism of controlled DCD on the basis of violating the dead donor rule, where autoresuscitation has not been described beyond 2 minutes, in which life support is withdrawn and CPR is not provided, is not valid. However, any post mortem intervention that reestablishes brain blood flow should be prohibited. “In comparison to traditional practice, organ donation has forced the clarification of the diagnostic criteria for death and improved the rigour of the determinations.”[17]

Cryonics is thus in real trouble, and cryonicists are clueless. DCD is an ethical 3rd rail in medicine, and I am in intimate communication with what is going on. Quite the opposite of ‘enabling cryonics’ in a medical setting, as some individuals believe (most notably those currently managing Suspended Animation, Inc., (SA) of Boynton Beach, FL), it is very likely to shut it down. Any attempt to integrate cryonics with DCD, as SA has recently been attempting to do, will very likely explode, both in the faces of cryonicists, as well as those of any health care personnel involved. I know, and have coauthored, reviewed, or given input on, articles by Whetstine, Crippen, Bleck and others who are respected world authorities on the ethics of DCD, and here is the short and simple answer as to what is now happening. [16, 18-20]

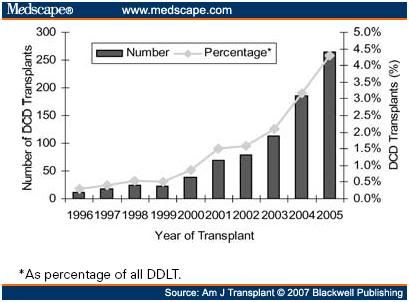

DCD is now a significant source of transplant organs in the US, and comprises rought 1/3rd of such organs in the Netherlands. It is growing at a nearly exponential rate (at left).

DCD is now a significant source of transplant organs in the US, and comprises rought 1/3rd of such organs in the Netherlands. It is growing at a nearly exponential rate (at left).

If DCD is to go forward, it will do so only on the basis of absolutely ensuring that no aspect of the procedure conserves, or in any way augments brain viability, or preserves brain structure, post-pronouncement. The people involved are very much aware of cryonics, and of the information-theoretic criterion for death; and most (but not all) either actively or quietly see ECMO and CPR in DCD as ways to shut cryonics down, or at least to greatly reduce its viability. There are myriad reasons for this; most not rooted in any overt hostility to cryonics, but rather in indifference and lack of understanding of any life saving potential in cryonics, as well as a quite justified (usually beneath the surface) discomfort/misunderstanding that cryonics is a 3rd rail in DCD (tit for tat, there), and that it has the potential to come into conflict with DCD, and thus with organ procurement. It is my opinion, that with one or two possible exceptions, people in cryonics today have little or no understanding of just how ‘ruthless’ organ procurement and DCD people are with respect to their own agenda. In fact, they (DCD professionals) show admirably more spunk, cunning, and naked self interest than I’ve ever observed in cryonics; and they are highly competent, articulate, and used to dealing with controversy, as well.

The UK has already adopted standards for determining and pronouncing death that expressly prohibit the application of CPR, or any modalities that restore flow to the brain or conserve brain viability. I have made inquiries, and been informed that failure to follow these Guidelines would be a serious breach of professional conduct, resulting in any licensed person being struck off; and that such action would very likely constitute a criminal act in the UK, as well (prosecution to be at the discretion of law enforcement and the prosecutor). [21]

Forty-Seven Years Ago: The right moral questions were not asked – nor answered – by us.

I was not present on the scene when cryonics was birthed in 1964, but I did arrive 4 years later. I thus have the unique advantages of have been there not just as a witness, but as an active participant in the promulgation of cryonics almost from the start of my involvement. This is relevant in that I can attest to the fact that no one at that time was doing anything other than operating in a reactive mode. We tried to answer their moral questions, instead of asking our own. At the time, we thought the those questions were just as foolish and irrelevant as now seems the case, two generations later. If you have two wives, you have a limited number of choices, and you’ll clearly have to make one – but at least you will be alive! Divorce, bigamy, a wife and mistress, or dumping both wives, beats being dead – and that is clearly a solution most of the rest world has come to see as eminently reasonable, and to adopt over the past 30 years, or so. But we were young and inexperienced and, above all, we were both ignorant, and eager to please. We desperately wanted cryonics to be accepted, and to be integrated into society – the society of 1964, of 1974 and even of 1984.

I was not present on the scene when cryonics was birthed in 1964, but I did arrive 4 years later. I thus have the unique advantages of have been there not just as a witness, but as an active participant in the promulgation of cryonics almost from the start of my involvement. This is relevant in that I can attest to the fact that no one at that time was doing anything other than operating in a reactive mode. We tried to answer their moral questions, instead of asking our own. At the time, we thought the those questions were just as foolish and irrelevant as now seems the case, two generations later. If you have two wives, you have a limited number of choices, and you’ll clearly have to make one – but at least you will be alive! Divorce, bigamy, a wife and mistress, or dumping both wives, beats being dead – and that is clearly a solution most of the rest world has come to see as eminently reasonable, and to adopt over the past 30 years, or so. But we were young and inexperienced and, above all, we were both ignorant, and eager to please. We desperately wanted cryonics to be accepted, and to be integrated into society – the society of 1964, of 1974 and even of 1984.

And then Dora Kent happened, and at that point we really should have come out from under the ether, and realized that what cryonics is really about, is revolutionary. The reason that we had gotten nowhere in 20 years, in terms of having cryonics more widely accepted, is not because of some failing on our part to craft the message just right. For years, almost from the moment it became apparent that the world was not going to embrace the idea with a bear hug of enthusiasm, a gnawing and highly counterproductive self doubt set in. What were we doing wrong? What public relations (PR) trick, or bit of finesse were we failing to understand, or master? This made us prey to an endless stream of PR kooks and creeps, as well as to some genuinely good men, who were simply as confused and misguided as we were – and for the same reason – because they too believed cryonics was a good idea.

Imagine, just for a moment, that a group of gay people show up at gathering of heterosexuals and try to sell them on the advantages of being gay, with the objective of convincing them to become practicing gay men and lesbians. Or, if you happen to be gay, you can imagine the reverse (except mostly, I imagine, you don’t have to). How successful would such an undertaking be? Clearly, it would wouldn’t be successful! Not only are straight people not gay people (or vice versa) they never will be – and all the PR and clever presentation, or even outright cash payments, are not going to change that!

The immediate objection to this analogy will, of course be, “Well, cryonics is different, it isn’t biologically determined.” To wit I would respond, “How many people have you converted to cryonics?” The answer is, usually, “None.” And that’s because the mechanisms that prevent people from understanding cryonics, and personally embracing it, are arguably as deeply embedded in most peoples’ personalities and psyches as is their sexual orientation, their religion, or their favorite color – at least for now.

To recruit people to cryonics is a generational undertaking that requires, at a minimum, changes in the culture media in which new human beings are incubated. It cannot, and will not be achieved by finding just the right slogan, launching just the right public relations campaign, or achieving that one singular event, such as cryopreserving just the right celebrity (it used to by that cryopreserving any celebrity would do the trick, however, since baseball great Ted Williams chose cryopreservation, that particular magic bullet has disappeared from the lexicon of quick fixes). And this situation is not our fault, anymore than death, or gravity are our personal responsibility. It just is, and we must accept it for what it is, stop blaming ourselves, and stop wasting time on foolish and nonproductive efforts to find the “magic bullet” that will make more cryonicists (like the Philosophers Stone that will turn dross into gold). Or, worse yet, waste our time talking about such nonsense, the way the Alchemists did for untold centuries, instead of getting down to the hard business of real chemistry and real physics.

The Life of Cryonicist Qua Cryonicist

Mathew Sullivan

“I’m fine with “looking beyond the lifespan of institutions (including nation states), but Mike (Darwin) is speaking from the perspective of organized resistance that is independent of the objectives of nation-states and any other human institution. I don’t see us as separate from society, but very much a part of it.Our true objective should be to evolve our process so that we can readily and seamlessly integrate with the medical establishment as various elements of the establishment open up to us.”

– Mathew Sullivan, January 13 2011 at 7:57 PM [2]

Ayn Rand

“”Mankind? It is an abstraction. There are, have been, and always will be, men and only men.” (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

I would change that to go one step further: man, only man.

Has there ever been a history written from the viewpoint not of a nation’s development through its outstanding individuals, but of these individuals’ desperate fight against their nations, for the sake of the development and advancement for which the nation so noisily and arrogantly takes credit after it has made a martyr of the “developer” and “advancer”? History is a deadly battle of the mass and the individual. A scientific task for me: to trace just how many of mankind’s “geniuses” were recognized and honored in their own time. And since they were not—as most of them weren’t—is there any ground for the conception of any national cultures, histories and civilizations? If there is any such thing as culture and its growth—isn’t it the culture of great individuals, of geniuses, not of nations or any other conglomerations of human creatures? And isn’t history the fight of mankind against advancement, not for it?”

–Ayn Rand, May 21, 1934

The moral questions we should have asked ourselves as cryonicists, no later than 07 January , 1988, [3] were what are the moral duties of a cryonicist, first to himself, then to the patients in storage, and finally to other cryonicists? Those were and are the important moral questions in cryonics, not whether cryonics is immoral because it might cause a man to have two wives, or even more unthinkably, a wife to have two husbands!

What are the moral obligations of a cryonicist to himself, to his cryonics organization, and to his fellow cryonicists – animate or cryopreserved? From these questions flow other, powerfully pragmatic questions:

What are the moral obligations of a cryonicist to himself, to his cryonics organization, and to his fellow cryonicists – animate or cryopreserved? From these questions flow other, powerfully pragmatic questions:

What is the moral thing to do if a cryonicist is dying and his brain (and thus his soul) is being eaten away by cancer, but the state says it would be homicide to cryopreserve him until long after his brain is gone, and his heart stops beating. In other words, until long after we know he his dead, even if they haven’t a clue?

What is the moral obligation of a cryonicist to himself if a nation-state, or some other “conglomeration of human creatures” demands that he go into battle and risk, or give his life for a war that he believes is pointless, or even cruelly counterproductive?

What is the moral obligation of a cryonicist to another dying cryonicist who is in unbearable agony and asks for surcease, and for freedom from the likelihood of significant, and equally likely irreversible peri-arrest ischemia?

And here, I will stop in my questioning, and observe that during the great dying that was the AIDS epidemic here in the US from~1983 to ~1996, many gay men acquitted themselves with greater courage and valor than any cryonicist that I know of has – because, by the thousands, in bedrooms and hospice rooms, and even in hospital rooms, they gave that release to those whom they loved – and did so without hesitation, without regret, and without ever speaking a word about it. I would estimate that 1 death in 3 in this cohort of dying men was ‘assisted,’ and mercifully so. We cryonicists should, on our best day, aspire to such courage – and to such compassion.

Mathew Sullivan’s words above are a sure and certain sign of both the moral, and the practical failure of cryonics, to date. Coming as they do from a cryonicist, they are shameful, and worthy of our pity, more than our censure, because, above all, they are foolish.[4] At the core of the philosophy of cryonics is the cry and the admonition of Alan Harrington: “Death is an imposition upon the human race, and is no longer acceptable.” [22] Harrington did not speak of death as an abstract, nor did he speak of death in terms of the species. Rather, he titled his work The Immortalist, and he spoke of the biological immortality of the individual; of individual men existing for a potentially infinite, or indeterminate length of time – not of immortality for the herd, or the species.

Even if we could be, which we can’t, do we really want to be “not separate from this society, but very much a part of it?” Look around you; we are surrounded by madmen who cannot even grasp the penultimate importance of their own lives, and who run headlong into the arms of death for the basest and most senseless of reasons. Is that mindless rabble what we want to identify with and become, or failing that, have them accept us? Should “our true objective be to evolve our process so that we can readily and seamlessly integrate with the medical establishment as various elements of the establishment open up to us?” Do we want to integrate with a medical establishment that persists in foolish, and above all irrational incantations and rituals, rather than in the exercise of science and reason, to determine when death is? In there is a typographical error in that sentence, because were we to “seamlessly integrate” with medicine, we would be forced to devolve our processes, not evolve them.

Curtis Henderson, Esq.

Two years before he entered cryopreservation, I accompanied Curtis Henderson on as visit to a physician. He was hard of hearing and irascible, and it was often difficult for him to communicate well with those from whom he sought treatment. As he was being examined, he made a reasonable complaint about how awful it was to be in his physical condition – aged, hard of hearing, on the anticoagulant drug Coumadin, which required frequent blood tests… The treating physician admonished him that he, “…should be grateful for his state of health at the age of 80, and for the excellent medicine which made it possible.” To which Curtis replied, “What is the matter with you people? You come in here day after day and you see people disintegrating – do you understand me – disintegrating right in front of your eyes. You can’t possibly miss it! Don’t you realize that this is going to happen to you, that it’s going to be you sitting here in my place? And that very soon after that you will be dead! It isn’t my heart or my liver, it is aging – aging is the problem. Fix that and you won’t have to put up with likes of me ever again!”

Mike Darwin

The doctor looked at me in that expectant, patronizing way that the young do when the elderly ‘act up,’ expecting some calming and reassuring words to spill from my mouth, no doubt accompanied by a condescending smile. Instead, what he got was a hard, cold stare and the unflinching words, “You should listen to the man, because he happens to be absolutely right.”

At the launch of the cryonics movement, Robert Ettinger got it right when he said, “This is not a hobby or conversation piece: it is the principal activity of this phase of our lives; it is the struggle for survival. Drive a used car if the cost of a new one interferes. Divorce your wife if she will not cooperate. Save your money; get another job and save more money. Sometimes a fool will blunder through, but don’t count on it. The universe has no malice, but neither has it mercy, and a miss is as good as a mile.” And then he lost his nerve, or lost his way, or maybe some of both. It’s an easy thing to do in a world full of threatening, coercive, and scary, crazy people.

So, what are the answers to those moral questions that I asked in the preceding paragraphs? The immediate answer, is that for now it is for us cryonicists to know, and for the rest of the world to find out. We can hope that they will come to their senses and that they will progress from the confines of that barred crib, in that dark nursery in which they were raised. And we should try, as best we can, to help them out of the darkness and into the light. But never, absolutely never at price of our lives, or of our sovereignty as cryonicists. We do have obligations to nation states, as well as to those of our fellow men who persist in their pursuit of mortality. But those obligations are of our choosing, not theirs, and they will be fulfilled on our terms and in our own good time.

So, what are the answers to those moral questions that I asked in the preceding paragraphs? The immediate answer, is that for now it is for us cryonicists to know, and for the rest of the world to find out. We can hope that they will come to their senses and that they will progress from the confines of that barred crib, in that dark nursery in which they were raised. And we should try, as best we can, to help them out of the darkness and into the light. But never, absolutely never at price of our lives, or of our sovereignty as cryonicists. We do have obligations to nation states, as well as to those of our fellow men who persist in their pursuit of mortality. But those obligations are of our choosing, not theirs, and they will be fulfilled on our terms and in our own good time.

And as to what those obligations are? Well, again, that’s a secret we share – something for us to know and for them to find out.

Footnotes

[1] Morals define personal character, while ethics stress a social system in which those morals are applied. In other words, ethics point to standards or codes of behavior expected by the group to which the individual belongs. This could be national ethics, social ethics, company ethics, professional ethics, or even family ethics. So while a person’s moral code is usually unchanging, the ethics he or she practices can be other-dependent.

[2] http://www.network54.com/Forum/291677/message/1294966668/Re-+Thomas+Donaldson+said+something+similar.

[3] When the Riverside County Coroner’s Office served a search warrant on Alcor, and six people, including me, were arrested in handcuffs.

[4] Foolish: not sensible: showing, or resulting from, a lack of good sense or judgment.

References

1) Verheijde JL, Rady MY, McGregor J Recovery of transplantable organs after cardiac or circulatory death: Transforming the paradigm for the ethics of organ donation. Philos Ethics Humanit Med 2007 , 2(1):8. PubMed Abstract | BioMed Central Full Text | PubMed Central Full Text

2) D’Alessandro AM The process of donation after cardiac death: a US perspective. Transplant Rev 2007 , 21(4):230-236. Publisher Full Text

3) Beecher H, Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School to Examine the Definition of Brain-death A definition of irreversible coma. Special communication: report of the Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School to Examine the Definition of Brain Death. JAMA 1968 , 205:337-340. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

4) Joffe AR The ethics of donation and transplantation: are definitions of death being distorted for organ transplantation? Philos Ethics Humanit Med 2007 , 2(1):28. PubMed Abstract | BioMed Central Full Text | PubMed Central Full Text

5) Crippen D Donation after cardiac death: Should we fear the reaper? Crit Care Med 2008 , 36(4):1363-1364. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

6) Sung RS, Punch JD Uncontrolled DCDs: The Next Step? Am J Transplant 2006 , 6(7):1505-1506. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

7) Childress JF Organ Donation after Circulatory Determination of Death: Lessons and Unresolved Controversies. J Law, Med Ethics 2008 , 36(4):766-771. Publisher Full Text

8) Miller FG, Truog RD Rethinking the ethics of vital organ donations. Hastings Cent Rep 2008 , 38(6):38-48. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

9) Magliocca JF, Magee JC, Rowe SA, Gravel MT, Chenault RH 2nd, Merion RM, Punch JD, Bartlett RH, Hemmila MR Extracorporeal support for organ donation after cardiac death effectively expands the donor pool. J Trauma 2005 , 58:1095-1101. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

10) Verheijde JL, Rady MY, McGregor J Recovery of transplantable organs after cardiac or circulatory death: Transforming the paradigm for the ethics of organ donation. Philos Ethics Humanit Med 2007 , 2(1):8. PubMed Abstract | BioMed Central Full Text | PubMed Central Full Text

11) Bernat, J. L., A. M. D’Alessandro, F. K. Port, T. P. Bleck, S. O. Heard, J. Medina, S. H. Rosenbaum, et al. 2006. Report of a national conference on donation after cardiac death. American Journal of Transplantation : Official Journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons 6, (2) (Feb): 281-91.

12) Bernat, J. L. 2010. How the distinction between “irreversible” and “permanent” illuminates circulatory-respiratory death determination. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 2010;35:epub ahead of print.

13) Bernat JL Are Organ Donors after Cardiac death Really Dead? J Clin Ethics 2006 , 17(2):122-132. PubMed Abstract

14) McGregor JL, Verheijde JL, Rady MY Do Donation After Cardiac Death Protocols Violate Criminal Homicide Statutes? Med Law 2008 , 27(2):241-257. PubMed Abstract

15) Tibballs J The non-compliance of clinical guidelines for organ donation with Australian statute law. J Law Med 2008 , 16(2):335-355. PubMed Abstract

16) Whetstine, L, Streat, S., Darwin, M, Crippen, D. Pro/con ethics debate: When is dead really dead? Crit Care. 2005; 9(6): 538–542. Published online 2005 October 31 Full Text: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1414041/

17) Shemie, DL. Clarifying the paradigm for the ethics of donation and transplantation: Was ‘dead’ really so clear before organ donation? Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2007; 2: 18. Published online 2007 August 24. doi: 10.1186/1747-5341-2-18.PMCID: PMC204897

18) Bernat, J. L. 2010. Capron AM, Bleck TP, et al. The circulatory-respiratory determination of death in organ donation. Critical Care Medicine 2010;38:963-970.

19) Crippen, DW, Whetstine, L. Ethics review: Dark angels – the problem of death in intensive care. Crit Care. 2007; 11(1): 202. Published online 2007 January 17. doi: 10.1186/cc5138.

20) Mamula, KB. Defining death sparks debate: Need for organs raises tough questions. Pittsburgh Business Times. Date: Monday, December 24, 2007, 12:00am EST – Last Modified: Thursday, December 20, 2007, 12:46pm EST. Defining death sparks debate | Pittsburgh Business Times

21) Simpson P. Letter from Dr. Peter Simpson, Working Party Chairman President, Royal College of Anaesthetists soliciting comments on the Revised Code of Practice for the Diagnosis and Certification of Death in Britain. In; 2007.

22) Harrington, A. The Immortalist. Celestial Arts; First Printing edition (February 1, 1977). ISBN-10: 0890871353

Very nice blog and I’ll visit frequently. I enrolled in Alcor some months ago because I’m so intrigued by this concept and as a physician believe that the underlying assumptions are sound.

What I wonder about is why more people don’t find this idea as exciting as I do, perhaps we are wired to accept the inevitability of death and so can’t psychologically see that there may be other options?

What I’d like to see is something like the X prize but for cryonics research – for example, demonstrate eeg activity in a mammal after cryopreservation and revival is a $100,000 prize, etc.

First, thank you for your positive comments about Chronosphere.

Now that we have that out of the way, I want to say, immediately, that if you are physician, then cryonics desperately needs your talents, on every level that you may choose to make them available. I’m afraid the first round of MDs I recruited in the 1980s are all used up – either cryopreserved, or driven mad by being in close proximity to cryonics for too long. But either way – no longer of the use they once were ;-). Ans while I am joking here (a little), I’m also really serious. There are literally a dozen ways I can think of, offhand, that you could materially contribute to progress, even if you live a safe distance from any hands-on cryonics activity.

At a minimum, I have at least 50 questions for you, starting with ‘trivial’ ones, such as how you heard about cryonics, how long it took you before you thought it made sense, how long it then took you to sign-up, what your colleagues, spouse/SO and friends think…to more serious questions such as what your medical specialty is, what kind of medicine you currently practice, your approximate age… Providing you choose to answer the latter questions, you needn’t do so publicly, but I think it would be of general interest, and possibly of some use if you commented on the former ones, here.

Cryonics has a peculiar history with respect to physicians in that there have almost always been one or more seriously involved as activist members, and there are a disproportionate number in cryopreservation, compared to the demographics of the general population. Ironically, I was working on finishing the technical case report on a physician I helped cryopreserve in March of 1989, Dr. Eugene Donovan: http://www.alcor.org/Library/html/casereport9002.html. [The technical case report was written at the time, but due to technological limitations, it was not possible to graph all the data or integrate photos - unfortunately, this task is not much easier now, due to formatting changes in software, so I have to re-enter much the numeric data by hand.] I don’t know what the current statistics are on the number of physicians per capita of patients at Alcor or CI, but I would think it would have to be between 4-6% at Alcor.

I guess I should also point out that the high number of docs in cryogenic storage is not an artifact of any wickedness on our part – but rather, just a consequence of human biology and the passage of time. If you want my email address, just ask. – Mike Darwin

“The UK has already adopted standards for determining and pronouncing death that expressly prohibit the application of CPR, or any modalities that restore flow to the brain or conserve brain viability. I have made inquiries, and been informed that failure to follow these Guidelines would be a serious breach of professional conduct, resulting in any licensed person being struck off; and that such action would very likely constitute a criminal act in the UK, as well (prosecution to be at the discretion of law enforcement and the prosecutor). [21]”

Are these guidelines applied to non-organ donors?

The answer to your question is, yes, the UK Guidelines apply to all persons pronounced dead in the UK on the basis of cardiorespiratory, or ‘clinical’ criteria. The prohibitions against the restoration of any life sustaining perfusion apply to all persons, not just those who are organ donors. The cover sheet on the 2006 draft of the proposed guidelines made this clear:

“The Academy of Medical Royal Colleges and the Department of Health have requested a revision of the 1998 document “Code of Practice for the Diagnosis of Brain Stem Death”. This resulting Revised Code of Practice has been prepared by a Working Party established through the Royal College of Anesthetists on behalf of the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges and the English Department of Health. This code of practice is designed to address the diagnosis and certification of death in all situations and to make practical recommendations which are acceptable both to the relatives of the deceased, to society in general and also to the medical, nursing and other professional staff involved. “

And I believe that similar, if not identical language is present in or on the regulations when they were distributed prior to implementation. The full text of the Revised Guidelines is available at: http://www.aic.cuhk.edu.hk/web8/Brain%20death%20code%20of%20practice.htm

Because I have good friends in Britain who are Intensivists, and also some practicing Anesthetists (ICU medicine grew out of anesthesia in the UK) I was alerted to the proposed changes in the Guidelines in 2006, and provided with a draft copy of them. At that time I immediately contacted all of the individuals/organizations in cryonics who I could think of, who would have a material interest in seeing these regulations exempt cryonics, and I urged them to form a working committee or to appoint a representative or hire a barrister to provide input to the Royal College to exclude cryonics from the prohibition against restoration of post-pronouncement perfusion. This included the CEO and Suspension Team Leader of Alcor, Alan Sinclair, then President of CUK, and Garret Smyth. I believe I also copied former UK cryonics activist and former cryonicist Mike Price. CI was notified, perhaps a year later. I received no response to these communications.”

Subsequently, I wrote an article entitled “How Dead is Dead Enough” which was published on Aschwin deWolf’s blog, Depressed Metabolism on 30 April, 2008: http://www.depressedmetabolism.com/how-dead-is-dead-enough/

In that article I say the following in regard to the change in criteria for pronouncing death in the UK:

“The British Catastrophe?

Many in the cryonics community seem to regard the likelihood of a medico-legal ban on cryonics stabilization procedures as something abstract, remote, and not likely to occur in the absence of some provoking event. For cryonicists living in Britain (and arguably all of the United Kingdom) prohibition of the application of any kind of circulatory support to patients pronounced dead by clinical criteria appears close to being a reality if it has not already occurred. In April of 2006 a Working Party established through the Royal College of Anaesthetists on behalf of the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges and the English Department of Health presented a draft of “A Code of Practice for the Diagnosis and Certification of Death” which substantially revises the 1998 “Code of Practice for the Diagnosis of Brain Stem Death.”

A major reason this revision was undertaken was to prevent the immediate post-pronouncement use of non-beating heart donors (NBHD) in organ transplantation. NBHD is highly controversial in much of the western world since it typically involves rapid post mortem interventions to protect the donor’s organs from ischemic injury including the application of CPR (51) and often the use of cardiopulmonary bypass to maintain organ viability (39), (52), (53). The use of immediately applied post-pronouncement preservation techniques has become routine in the Netherlands and organs from NBHD donors now constitutes 40% of kidneys transplanted there (54). The revised British code of practice expressly forbids application of any kind of cardiopulmonary support (both CPR and CPB) to patients pronounced dead on the basis of clinical criteria (as opposed to those pronounced dead by neurological or so-called “brain death” criteria. Discussion on the draft document was closed on 18 August, 2006 (55) and the code was scheduled to be adopted before January of 2007†. The last paragraph of the revised code under the subheading “Certifying Death After Cardiorespiratory Arrest” clearly states:

“It is obviously inappropriate to initiate any intervention that has the potential to restore coronary or cerebral perfusion, including chest compressions or the institution of cardiopulmonary bypass after death has been certified.”

This document also, for the first time, establishes a prescribed evaluation (waiting) period for determining cardiorespiratory arrest, namely 5 minutes. This development demonstrates clearly that events in biomedicine far removed from the concerns of cryonicists can have profound negative impact – not all biomedical advances promise beneficence. Here in the U.S. the debate over NBHD has become intense and often bitter (56), (57), (58),. It seems well within the realm of possibility that the actions of some transplant surgeons and patient advocacy groups who are pushing the envelope to expand NBHD may result in a similar revision to U.S. law (59), (60).

59. Cole D. Statutory definitions of death and the management of terminally ill patients who may become organ donors after death. Kennedy Inst Ethics J 1993;3(2):145-55.

60. Brook N, Waller, JR, Nicholson, ML. Nonheart-beating kidney donation: current practice and future developments. Kidney Int 2003;63(4):516-29.”

This article was published on DM, after being rejected for publication by both US cryonics organizations.

At around the same time the “How Dead” article was being prepared, I received information from a friend I have in organ procurement here in the US, that the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws (NCCUSL), was in the process of beginning a revision to the Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA), as well as to the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act (UAGA). They were conducting an ‘open meeting’ in Hilton Head, SC to solicit input from all parties with an interest in amending these acts, with the focus being on the UAGA. Invited parties were the funeral services industry, the tissue banking industry, organ and tissue procurement agencies, and any others who might be materially affected by changes in the law. Again, I notified the US cryonics organizations, and this time I received a response from Steve vanSickle of Alcor, stating that the relevant people in management had prior obligations during the time the Hilton Head meeting was to take place.

As is the case with the Royal College of Anesthetists in the UK, the NCCUSL, despite its government-sounding title, is in fact a non-government body. It was created about 120 years ago by a group of lawyers, in response to the chaos resulting from widely varying laws between states – laws that were impacting both interstate commerce, and the professions. The US differs greatly from most other countries in that the states have strong rights, independent of the Federal government. Thus, you can serve a long sentence in prison in one state, for an act that is perfectly legal in others. To help resolve these conflicts where critical issues of law were involved regarding (mostly) commerce, a group of lawyers formed the NCCUSL and began drafting “Uniform Laws” – two such laws are the UDDA and the UAGA. However, these are not really laws, but rather a suggested template, which each state can use as they choose, or not. Thus, both the UAGA and the UDDA vary substantially between states, and some states adopted neither, but rather went with their own language. It is thus necessary to pay very careful attention to individual state’s SPECIFIC laws when dealing with the pronouncement of death, or the donation of organs or tissues. Even those states that adopt the Uniform Law usually modify it extensively.

I do not know what the status or outcome of the proposed revision of the UAGA was – but I assume it has been made, and is now out there for the states to use as they please. Once the Uniform Law is completed and ‘proposed’, NCCUSL will not alter it. Thus, the only recourse in that situation is to go state-by-state and lobby for changes to the law – an incredibly costly, and usually hopeless undertaking: this is why NCCUSL encourages participation and input by all affected parties – large or small – during the drafting process.

Mike Darwin

“The immediate objection to this analogy will, of course be, “Well, cryonics is different, it isn’t biologically determined.” To wit I would respond, “How many people have you converted to cryonics?” The answer is, usually, “None.” And that’s because the mechanisms that prevent people from understanding cryonics, and personally embracing it, are arguably as deeply embedded in most peoples’ personalities and psyches as is their sexual orientation, their religion, or their favorite color – at least for now.”

You could say the same thing about people not embracing libertarianism and/or atheism. I’ve seen this first hand: A group of activists imagines that since their ideas are so right or so logical, all one has to do is hone one’s debating skills and start the conversions. These activists all fancy themselves as being a Mr. Spock, whose job is to convince Captain Kirk and Doctor Mc Coy to do the logical and rational thing. However, after years of hard work, they almost always become burnt out and are befuddled that the masses don’t accept their brilliant arguments and logic. “After all, how can a sensible person accept God or think socialism is a great idea?” “Where did we go wrong?” they wail as they tear out their hair.

The problem is, as Mike Darwin notes, that people who embrace fringe ideas like cryonics, libertarianism or atheism DO NOT think like other people and no marketing campaign is going to change that. Sure, people can change, but it’s rarely because of brilliant minds talking people out of their old beliefs. Social change generally has little to do with “arguments. ” For example, why is homosexuality increasingly accepted in the West? Not because of “arguments”—the real reasons include everything from the birth control pill, modern capitalism , the decline of Orthodox Christianity, people coming out of the closet and old conservative people dying off. But it’s certainly not because some philosophers convinced the masses that hatred of gays was “illogical .”

But still, like Charlie Brown attempting to kick the football after Lucy has pulled it away a hundred times, people keep trying the same failed things over and over. History repeats itself first as tragedy — and then as farce many times over.

I suspect generational turnover may have imperiled cryonics. How many cryonicists alive now remember the moon landings and have long assumed that we live in a “space age” of increasingly ambitious manned space travel, and we therefore looked to cryotransport as a means of reaching an era with more advanced astronautical capabilities where we could get our share of that, even to the point of becoming interstellar explorers with our upgraded bodies and greatly extended lives? Consider how many cryonicists passed through the long-defunct L-5 Society, for example, myself included.

Well, we know how progress in astronautics has turned out so far, despite the recurring progress porn about sending people to Mars, now with the intention of leaving them to die there. (I doubt that a “Mars colony” would put building a cryonics facility high on its list of priorities.)

Younger people in my experience don’t find the idea of manned space exploration compelling, and cryonics’ association with that sort of futurology from the 1960′s and 1970′s has given it a paleofuturistic reputation, in the neighborhood of flying cars, geodesic domes and jet packs. I submit that the association of Drexler’s “nanotechnology” with cryonics, still a no-show after 30 years, doesn’t help cryonics’ credibility either.

So how do we rebrand cryonics to make it cognitively accessible to people who don’t remember the moon landings? Do we have to call it “iFreeze” or something?

For example, if someone invented cryonics now as a new idea, based on today’s science and technology, and on current assumptions about “the future,” what would it look like?

Your comments are insightful, accurate, and welcomed here. I think in large measure what we are seeing is a result of several things – some new, and some very old. The new things are that the speed of social change, driven by technological advance, is enormous compared to what has been the norm for the human experience. I explored this idea in a piece I wrote (but did not publish) a few years ago entitled, “The 3,000 Year Old Man: Me,” which I may post to Chronosphere sometime. And we are living longer as individuals and this provides us with a taste of what it will be like if humans really do achieve vast life span extension.

The importance of the second point is that it is now possible to see both how and why some novel technologies are embraced and developed, and how and why some aren’t. Jules Verne’s Captain Nemo is a profoundly humane and profoundly anti-authoritarian hero. He creates the Nautilus, and wields it as he does, because he is both frustrated and disgusted at how humanity uses powerful new technologies (and please, don’t confuse Verne’s Nemo with the psychopathic rendering of him in the Disney film version of Verne’s novel). My lengthily footnote about Werner von Braun in the “Technological Inevitability” piece annoyed several people, who considered it out of place. My point was that von Braun could have cared less about Nazi ideology or about WWII in general; he considered both an irritating distraction, as well as an enabling series of events for the technology he wanted to develop – namely the ‘space colonization’ of your “paleofuture.” The point is that the Nautilus (literally) that became a reality was not the one Verne ‘invented,’ but rather was a tool of war, of total war that was the polar opposite of what Captain “No One” stood for, and wanted. Similarly, the liquid fueled, multi-stage rocket capable of interplanetary travel, and of opening up the stars to human kind, was not implemented as the device its two primary creators dreamed of and longed for. Both Werner von Braun and Sergei Korolev wanted the moon, Mars and the stars. But the civilization they were embedded in wanted intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) to deliver massively destructive thermonuclear weapons capable of utterly destroying civilization – rather than spreading it amongst the stars! Thus, the only reason these technologies became a reality was because they were good for warfare.

Now that the pace of technological advance has become lightning fast by historical standards and we are living longer (on average) and have more ‘leisure’ time to reflect on our life and times as “average Joes,” it possible to see that a big hunk of technical advance, and the choice of which technologies are developed, is a function of their military utility and the core values of the cultures that develop them – or choose not to. The fictional Nemo, and the very real Korolev and von Braun, never reflected or represented the values of their respective cultures, or of their (and our) civilization. If you would understand the reason for the paleofuture bill of goods our generation was sold, it is necessary to understand that Kennedy and Khrushchev’s bold and inspiring words about the “conquest of space” were lies. They were just so much political rhetoric to justify the expenditure of an unbelievable fraction of their respective nation-states’ GDPs on weapons of mass destruction. The vehicle that carried Vokstok 1 and Yuri Gagarin into orbit, and the Redstone rocket that put John Glen (briefly) into space were ICBMs pressed clumsily into service for manned spaceflight as a politically expedient afterthought. No serious student of history would argue that either the US or the USSR manned space programs were anything but political theater. The Nazis had a wonderfully descriptive word for this kind of thing: propaganda (which, BTW, they used freely, and with a straight face).

A good hard look at history shows that the interests and expenditures of each successive generation are driven by a complex mix of factors. Near the top of the list is the politico-military situation of the time. Next are the fads, fashions, and pressures generated by the social and political milieu of the moment. Just like individuals, cultures only have a limited amount of time and attention. A given individual may be primarily interested in music and popular culture, getting ahead at work, being a soccer mom, or being a biker at any given point in time. Individuals can also make transitions between these lifestyles and priorities. What determines the predominance of the given mix of selections on the menu of lifestyles are the core values of the culture. Travel the world and truly move amongst its peoples and you will see this as a living, breathing reality. Not every society or culture wants what the West wants – although I would be the first to say that the differences are mostly superficial. No culture wants practical immortality, universal justice, and a truly long term view of life and individual humans’ role in it, to become a reality. These are as new and as profound ideas as are the rights of man, universal literacy, the abolition of slavery, and the ideal of capitalism (i.e., free movement of markets and peoples).

The irony is that most cryonicists still just ‘don’t get it.’ They want to pursue these powerful, incendiary, and utterly revolutionary ideas in the same way as they would hawk canned peas. They think, and honestly believe, that you can fill a trough with cyanide-laced Kool-Aid and then proceed to try to persuade the culture to drink it (and be grateful in the bargain) by finding the “right” Public Relations angle, or by bowing and scraping in just the right way. This is nonsense! The ideas I’ve just listed above are as toxic to the current world order as were the Magna Carta and the US Declaration of Independence to the old world order. Fortunately, people like Thomas Paine and Thomas Jefferson ‘got it,’ and didn’t try to bow or scrape their way into favor with the powers that were. The US Revolutionary War was not primarily about serious economic or social injustice in the framework of the times. The nascent nation-state that would become the US had no truly serious economic gripe with the British Empire. Nor was their an insurgency, or any other kind of local terror, or intolerable lawlessness (a major driver of revolutions). The central change that drove that Revolution was a novel ideology – not economic expedience, or the necessity to re-establish law and order.

Most cryonicists just don’t get it – they don’t understand that the values and the apparatus that enforces them are LITERALLY KILLING US, EN MASSE, RIGHT NOW! Look at the numbers. Easily one third of the patients now being cryopreserved are chopped up or sit around for days before they can be treated and stabilized. Of those who get the “best” treatment, at least a third, and probably more like 90% (at present) have ischemic intervals that run to many minutes or many hours! These patients almost certainly have little (or more likely) no chance of being recovered with their declarative (biographical) memories intact – or even with their memories present at all in any integrated, narrative form. Most cryonicists have made the lethal error of confusing the fact that someone can be revived in the case of virtually every cryonics patient now in storage, with the idea that that “someone” will be the same person who was cryopreserved to begin with. Not even the most conservative, rational biomedical scientist would argue that it is impossible to clone humans. That means that, at a minimum, every cryopatient now in storage can be revived – if your criterion for revival is a “continuer” who shares the original person’s genome and its epigenetic implementation. That’s not what I want, and I don’t think it is what most cryonicists want – or expect.

Any careful reading of Ettinger’s writings over the years will reveal that he does not consider biographical memory central to, or an essential requirement for survival of the individual. Rather, he believes in some hypothetical arrangement of neurons which he terms “the self-circuit” that constitutes and enables each (presumably?) “unique” individual. Of course, he is entitled to that point of view, and it goes a long way to explaining the reality of CI’s practical indifference to the details of how its patients get cryopreserved. “Frozen is frozen; and a bicycle is a Yugo is a Mercedes.” I don’t agree with this position, although it would be very convenient to do so, because in practice what this means is that any blob of decomposing protoplasm that makes it into cryogenic storage is a PATIENT with the same (implied) chances of recovery as that of any other PATIENT. Just making it to -196 degrees C is, in effect, a ticket to ride to Resurrection Day.

That’s religion, and I can’t (or more properly won’t) argue with the right of people to choose that kind of ritual-based comfort. What it is not is scientific cryonics – something that is feedback driven, employs the corrective mechanism of the scientific method, and yields steady and demonstrable improvements in the quality of treatment. It also doesn’t “rock the boat,” in that as clinical and forensic medicine produce more and more severely injured and degraded patients as halfway medicine advances, the cryonics community will remain nonplussed.

Consider that in 14 years the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) will be 18% of the population in the developed Western world! By 2025 the percentage of end-stage AD and other dementias as the cause of death will be approaching 40%! Add to that the percentage of patients who will suffer cardiac arrest from massive stroke and other brain destroying diseases, and the number of people who really are DEAD by the time they present for cryopreservation is pushing 50%! If you then add in autopsy (or long delays until the patient is released) with consequent straight freezing, it becomes pretty clear that conventional medicine will have at long last converged with cryonicists’ definition of death. In other words, when they say you are dead, you really will be dead – by the information theoretic criterion (ITC). This “advance” towards a convergence between the point where conventional medicine “abandons” its patients and pronounces them dead, and the point where the ITC says you are dead, is already well underway. In 1964 when cryonics was launched most people died of things that left their brains intact. As medicine “squares the curve” it is progressively shifting the cause of death to brain failure. Most of the people in extended care facilities today are there because there is something profoundly wrong with their brains. You can be very physically disabled and still live independently. But serious cognitive disability is immediately disabling and requires vigilant and fantastically costly care. Look at these numbers:

• Average lifetime cost of care is $170,000 (American Journal of Public Health, 1994)

• Costs businesses $61 billion each year in America (Alzheimer’s Association, 2002)

• Government expects to spend $640 million for research of the disease in America 2003 (Alzheimer’s Association, 2004)

• $5.5 billion each year in Canada (Canadian Medical Association, 1994)

• $36,794 per individual with a severe case in Canada (Canadian Medical Association, 1994)

• $9,451 per individual with a mild case in Canada (Canadian Medical Association, 1998)

Read more at http://www.wrongdiagnosis.com/a/alzheimers_disease/stats.htm?ktrack=kcplink#society_stats

Anyone who thinks there will be a cure for AD in 14 years is just plain foolish. And even if a cure were developed tomorrow, it would only shift the cause of death from AD to the “normal cerebral atrophy of aging.” If you never get AD, you will still be losing ~80K neurons per day (from age 2 onward), and by the time you are 70 your brain mass will have decreased by a third!

The point is that today’s cryonicists will absolutely confront these realities and that, as a consequence, cryonics is mostly an empty promise for us – just a much crueler version of the paleofuture you are already mourning the loss of. And if we choose to not accept that version of our future, then we are at odds with the existing social and cultural order.

It’s as simple as that. – Mike Darwin

Does your website have a contact page? I’m having problems locating it but, I’d like to shoot you an email. I’ve got some recommendations for your blog you might be interested in hearing. Either way, great site and I look forward to seeing it improve over time.