By Mike Darwin

Cryonics: A Failure of Nocioception

“The Birth of Cryonics”

“The Birth of Cryonics”

Figure 1: Worldwide there are currently 67 people known to have congenital insensitivity to pain with anhidrosis, or CIPA. It is an exceeding rare genetic disorder that renders those who have it unable to feel pain, or to sense temperature. Far from being a blessing, this inability to feel pain or discomfort, or to sense extremes of temperature, curses the person with CIPA to live in a world free from the normal feedback that allows us to learn how to behave safely, and to avoid constantly and unintentionally injuring ourselves. Regrettably, humans are not the only entity to suffer as a result of the lack of nocioception, so do some of their institutions, most notably, cryonics organizations.

Onto 50 years ago now, the newborn that was cryonics was held up before the world and cried out lustily. And the world heard that cry and took note. From the tabloids to the learned journals, the infant’s birth was cataloged and commented upon. Some greeted it with wonder, some with puzzlement, and some with the contempt that was reserved for the bastard child of any culture at that time.

The infant appeared healthy, and fought and struggled its way into life with the best of them. But hidden, locked within its DNA, was a potentially fatal defect. The tragedy was that this child could not feel pain. Whereas the normal growing child would learn quickly, automatically, and without instruction not to touch things that were too hot, or too cold, too sharp, or jagged – or how to run and play without rending flesh, or breaking bones – this child would not – could not learn. For this child, every danger life presented would require a consciously learned response – not something fast and instinctive, but something laborious, and artificial. The simple act of eating a meal could result in a severe scalding, or the inadvertent and unfelt amputation of the tip of the tongue while chewing. This child would never feel pain, and was therefore damned to a life of unintentional self mutilation.

If cryonics had been a human child, then seven years ago the scientists and physicians who study such things would finally have discovered that cause of this remarkable affliction was the disarrangement of a few base pairs, on something called the SCN9A gene. [1] But they would still be powerless to fix it.

In 1986 I wrote an article entitled the ‘Myth of the Golden Scalpel,’[1] which first delineated the problem of ‘no feedback’ in cryonics. The problem with cryonics is that neither the patient, nor their family (or other interested parties), will experience any objectifiable results or outcome from the procedure; at least not in their lifetimes.[2,3] As I wrote at the time: “There is no feedback: no normal corrective market mechanisms; no crippled patient, no person in pain, and no loss suffered and reported upon as a result of flawed cryonics procedures. A badly cryopreserved patient looks as good as, or better than, a well cryopreserved patient. Shortcuts, missteps, and even outright negligence that severely injure cryonics patients cannot be detected or remedied if the patient, or those caring for him, has no way of knowing that such damaging events have occurred.”

Thus, as is the case of the child born with no nocioception – no ability to feel pain, cryonics will be vulnerable to errors and disasters that would have easily been avoidable if only someone, somewhere, suffered now – and not a hundred years from now. I saw this as a corrosive, single point of failure that would ultimately degrade, or even destroy cryonics as a whole, unless what I termed “artificial” or “surrogate” feedback mechanisms, such as” laboratory evaluation of markers of injury, meticulous documentation of the physical procedures employed, and surrogate markers for brain viability were put into place and adhered to.” [3]

The “Golden Scalpel” article was a response to intense criticism of the application of an evidence based, medical model to cryonics, and the associated increase in costs and, perhaps just as importantly, the accompanying disempowerment of ‘amateurs.’ Prior to the entry of professionals – or people working to create professionalism in cryonics – cryonics was a ‘do it yourself’ (DIY) undertaking, and anybody could (and did) undertake to cryopreserve people. A corollary of this was that anyone’s opinions about how cryonics should be practiced were as good and as valued as anyone else’s. Much of this criticism came from members of the Bay Area Cryonics Society (BACS) and the Cryonics Institute (CI).

The “Golden Scalpel” article was a response to intense criticism of the application of an evidence based, medical model to cryonics, and the associated increase in costs and, perhaps just as importantly, the accompanying disempowerment of ‘amateurs.’ Prior to the entry of professionals – or people working to create professionalism in cryonics – cryonics was a ‘do it yourself’ (DIY) undertaking, and anybody could (and did) undertake to cryopreserve people. A corollary of this was that anyone’s opinions about how cryonics should be practiced were as good and as valued as anyone else’s. Much of this criticism came from members of the Bay Area Cryonics Society (BACS) and the Cryonics Institute (CI).

Figure 2: Before the arrival of Fred and Linda Chamberlain, Art Quaife, myself, and a few others, cryonics procedures involved no observation, measurement, or recording of physical or biological data of any kind. Patients were perfused with a small, fixed volume of low concentration cryoprotective solution, usually in a Ringer’s solution carrier, using an embalming pump. Cooling to solidification was uncontrolled and unmonitored; and was achieved by packing the patient in dry ice after wrapping him in aluminum foil. The pictures above are from a 1968 cryopreservation.

Figure 2: Before the arrival of Fred and Linda Chamberlain, Art Quaife, myself, and a few others, cryonics procedures involved no observation, measurement, or recording of physical or biological data of any kind. Patients were perfused with a small, fixed volume of low concentration cryoprotective solution, usually in a Ringer’s solution carrier, using an embalming pump. Cooling to solidification was uncontrolled and unmonitored; and was achieved by packing the patient in dry ice after wrapping him in aluminum foil. The pictures above are from a 1968 cryopreservation.

The kinds of procedures being used before the application of an evidence-based medical model to cryonics are best described as more akin to ritual, than science (see Figure 2). There were no tests, measurements, or evaluations performed to inform the people carrying out the cryopreservation procedures whether things went poorly or well, and whether the ‘standard’ procedure (or a modified one) was good or bad for a given patient. For instance, should patients with long ischemic times get a different treatment than patients with short, or very little ischemic time? Perhaps a more rapid increase in CPA concentration should be used, or even no CPA perfusion at all under some circumstances?

How and why such decisions are to be made should be documented and have a scientific basis which is continually being informed by ongoing research.

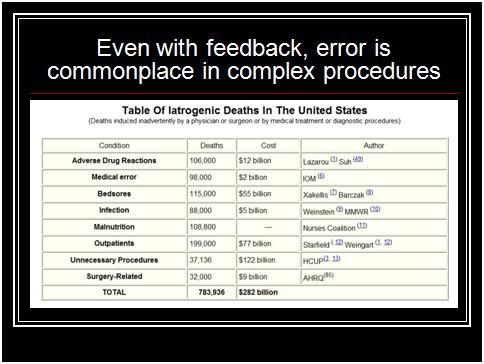

Figure 3: In the US each year there are in excess of three quarters of a million deaths due to medical error (iatrogenesis). Is US Health Really the Best in the World? Barbara Starfield, MD, MPH JAMA, July 26, 2000 – Vol 284, No. 4. p. 483 http://jama.ama-assn.org/content/284/4/483.extract http://www.avaresearch.com/ava-main-website/files/20100401061256.pdf?page=files/20100401061256.pdf

In conventional medicine, where personnel at all levels are extensively trained, those who control the discipline are highly educated and skilled professionals; there is licensing and government oversight, and extensive documentation of procedures and record keeping, lethal and morbid injuries are still surprisingly common. As you can see in Figure 3, in the US alone, there are over three quarters of a million deaths each year due to medical error (iatrogenesis).

This is a staggering number of deaths, and the associated cost is an estimated $282 billion! And keep in mind, this does not include the patients who are injured and do not die, or the many patients whose death or injury is either not detected, or not reported.

Figure 4: Surgical instruments left inside a patient, the wrong organ or limb being removed, and decubitus ulcers (bedsores) are but three of a wide range of common and completely avoidable iatrogenic errors.

As bad as the problem is, it would be much worse, if it were not for the fact that in medicine the patients being treated provide feedback. If you injure a patient delivering medical care, the odds are good that the patient will show both symptoms and signs of your error. He may suffer pain, become gravely ill, behave abnormally, lose sensory or motor function, be disfigured, or die.

The image at the right in Figure 4, above, of a decubitus ulcer – a bedsore or pressure sore, in common parlance – is due to failure to properly position and turn the patient. Bedsores are surprisingly common because the patient does not feel the discomfort until after the injury at the pressure point(s) has occurred. Patients in extended care facilities are also often effectively ‘voiceless objects,’ who are frequently demented and are often unable to speak articulately for themselves, even when compos mente. All too often they are also being warehoused and cared for by under-trained or under-motivated personnel.

Medicine also benefits from diagnostic modalities, such as the x-ray image at left in Figure 4, which allows for errors to be uncovered more effectively – and thus be corrected or mitigated – where it’s possible to do so.

Unfortunately, the cryonics patient can provide none of the feedback a living patient does, and as I have often said before, a patient who is straight frozen invariably looks far better, and far more lifelike and at peace, than does a patient who has received the best available care.

This is one of the reasons that cryonics has remained as small and as dysfunctional as it has, because leaving the general ability of this culture to perceive the value of cryonics out of the equation (nil), progress is rendered difficult, if not impossible, by the lack of feedback. Where feedback comes easily, is straightforward, and readily verifiable in cryonics, such as keeping patients refrigerated to liquid nitrogen temperature, the quality of care will at least be reasonable, because there is an objective ‘floor’ below which it is difficult to fall. The exception being any situation where even that part (storage) of the cryonics operation is shielded from scrutiny, as happened in the case of the Cryonics Society of California (e.g., Bob Nelson and Chatsworth). Feedback matters – in fact it is absolutely essential to the survival of any complex system, whether it be a human child, or a cryonics organization.

Cognitive Prosthetics

I have at least two developmental cognitive defects, perhaps related to inadvertent heavy metal intoxication when I was a toddler. I have severe cuts in my ability to recognize and manipulate numbers, and I have an inability to orient myself geographically, or to use maps effectively (small children are also unable to read maps, and this ability cannot be forced before certain biologically determined developmental milestones are reached). The relevance of these two (serious) handicaps to this discussion are that first of all, I do understand the problem of feedback inhibiting cognitive defects intimately, and, perhaps more importantly, I’ve recently come to understand that it is possible for technology to develop workable, if not foolproof cognitive prostheses, just as it is increasingly developing better prosthetics for lost limbs, and even internal organs (i.e., joint replacement, lens replacement in cataract and left ventricular assist devices).

Figure 5: If we want to attract more members – especially members who will be active in cryonics, and even serve as successors in its conduct, we must correct the ‘no-feedback’ problem, while at the same time involving and empowering those members in the correction process itself. The no-feedback problem in cryonics can only be corrected effectively and durably by making it a community wide responsibility – something that until very recently was not even technologically possible.

The advent of sophisticated calculation tools available as ‘clouds’ via my PC, has done much to help compensate for my vestigial math skills, and more dramatically, the advent of compact, hand-held GPS technology has proved liberating in a way I cannot begin to fully communicate. I can now travel freely – I do not have to persuade someone to go with me if I want to go someplace unfamiliar. As a result, my sense of anxiety and frustration whilst navigating unfamiliar cities has been replaced by cautious confidence. This has radically transformed my life by allowing me to travel freely, and to see and experience things I would never have previously been able to. Thus, for the first time, truly sophisticated cognitive prosthetics have been demonstrated to work, and to work reliably and robustly enough to allow a profound improvement in a severely handicapped person’s performance (and enjoyment) in life.

Augmenting Feedback in Cryonics

Technological advances have already made vastly improved artificial or augmented feedback possible in cryonics – they just haven’t been used. There are likely three reasons for this. The first is ignorance: GPS devices had been on the market for a decade before I found a slightly damaged one that had been discarded, repaired it (mostly out of curiosity), and only then experienced the powerful transformation in my life this technology made possible: a transformative technology I had lost out on for 10 years, only because I was effectively ignorant of its real capabilities!

The second problem, however, is a much harder one to surmount, and that is the problem of active resistance to change. To some extent, this is intrinsic in all individuals and institutions. We would go mad, and never get anything done if we were literally, constantly trying new things, instead of exploiting the tools and skills we have already mastered. But beyond that, and especially in the context of cryonics, augmented or prosthetic feedback means more work – a lot more work. And even more importantly, and obnoxiously (at least to some people) it means that, for the first time, outside forces will increasingly drive the direction and pace of their work.

Once feedback is introduced, it is no longer possible to decide upon, and then carry out a course of action without the real world intruding, and changing your direction, from time to time. In the case of my GPS, since it ‘knows’ where I am going long before I do, it can at least prepare me for a course change, and let me know that in 500 feet I’m going to have to make a right turn – or a left one – as the case may be. For me, this is wonderful and welcome instruction on how to reach my destination, because I know I’m lost without it. But, if you don’t think you are lost (or you really aren’t) then the feedback from the GPS telling you where to turn next will be an annoyance at best, and a deeply resented incursion into your autonomy, at worst.

Finally, some of the tools I’m about to describe will necessarily invade peoples’ sense of privacy. I say “sense” of privacy, because the whole concept of privacy as we know it is in the process of being obsoleted by technological advances. In a very real sense, we are returning to an environment which existed earlier in the history of the West, when dense urban environments, poverty, and population pressure had pretty much abolished privacy. In much of the Third World this is still the case: for instance, in much of the urban Arab world (Cairo is a good example) there is almost no easily accessible private space; absent a good bit of money to pay for it. Extended families live together, someone is always home, there are no private rooms except for married couples (until they have a child) and there are no, ‘no-tell motels,’ or similar venues. Literally every space is surveilled (or was before the recent revolution there) and there are strict rules on who you can check into a hotel with. Thus, the most common refuge for an average couple interested in a dalliance, is to rent a small boat (Felucca) and go out on the Nile – if they have the money, and if they can trust to their ferryman’s discretion.

Starting Simple

Figure 6: Well, at least they can’t screw up patient cryogenic storage. Or can they?

Figure 6: Well, at least they can’t screw up patient cryogenic storage. Or can they?

I said earlier that patient storage is one of the few feedback-driven areas of cryonics that provides for a ‘floor,’ beyond which it is hard for care to descend. And that is true, with a few important caveats. The first is that storage must be completely transparent. In reality, this is only relatively possible, because while allowing journalists and members access for inspection is a safeguard, it is so only to the extent the surveillance is complete – and of course, it can’t be. What is in fact being relied upon is that those delivering care won’t take the chance that occasional interruptions in the quality of care will escape undetected, such as, for instance, allowing the liquid nitrogen level to drop to the point that part of the patient becomes exposed.

Figure 7: A typical camera array on a street in the city of London, UK. Such arrays are omnipresent there, and London has become a panopticon.

Much more seriously, as was recently demonstrated in the case of the disgruntled former Alcor employee Larry Johnson, it is (given the current level of protection) quite possible for a deranged, or malicious employee to gain access to the patients and to do them harm without being detected.[2] It is chilling to read Johnson’s descriptions of how he evaded the inadequate surveillance camera coverage at Alcor.5

I do not want to seem too harsh on Alcor here, because Alcor did have cameras, and does lock its patient dewars. The Cryonics Institute does not even lock their patient dewars – this is an issue I have raised with their management several times over the years, but to no avail. Any careful reading of Johnson’s book, Frozen, should eliminate any doubt as to why locking access to the patients on multiple levels is not only desirable, it is essential.

In addition to further hardening facilities against intrusion, the best way to both build member confidence in the quality and consistency of cryogenic care, and to ensure that such care meets the highest standards at all times, is to make it completely transparent.

Consider London. London is now a city saturated with closed circuit TV cameras (CCTV). A typical CCTV array on a London street corner is shown in Figure 7, and the density of CCVT cameras per 1,000 persons is shown in Figure 8. As a consequence, it is now impossible to go anywhere in London without being captured on CCTV dozens of times per day. London, a city of 7.2 million people, is on the threshold of becoming an ‘urban panopticon:’it was estimated that there was one camera for every 14 people in the city as of 2003, with that number expected to rapidly rise.6 Privacy, as we have known it in the past, effectively no longer exists. And should you think this is only an urban phenomenon, consider that in the UK as a whole there are 4,285,000 cameras for the country’s 60 million residents, with that number expected to double within the decade.

Figure 8: Number of cameras per 1K people by region, in the city of London, as of 2003.6

Figure 8: Number of cameras per 1K people by region, in the city of London, as of 2003.6

Thus, two ways suggest themselves for making patient storage much more transparent to members, while at the same time improving the level security for the patients:

1) Place streaming webcams, operating 24/7, in the patient care bay that can be monitored at all times by any Alcor member in good standing.

2) Include in that data stream, or as an auxiliary data stream, continuous, or frequently updated temperature and/or liquid level monitoring data for every patient dewar. For those who have family members in storage, they can and should be provided with a labeled data stream, showing the temperature in the vessel where their relative, or significant other (SO) is stored.

Figure 9: In an era of very inexpensive cameras, and web video streaming technology, every Alcor Cryopreservation Member should have the ability to look in on the patient care bay at any time. This will build confidence, and it will also allow members to show family and friends the degree of intimacy and access they have with their cryonics organization.

In an era where people of average, or even modest means can bear the burden, both in time and in money, to enable such streaming video for a bitch and her pups, or an owl and her chicks, this is a perfectly reasonable safeguard to ask be put in place for cryopatients in storage. We are already at a point where our enemies have used these advances in imaging and computing technology against us: isn’t it time we started using them to our advantage?

Going Further: There’s an App for That!

A critical reading of the various case reports published by cryonics organizations makes it clear that there are truly horrible problems that are recurring over and over again in patient transport. Patients routinely arrest before the Standby Team arrives, after the team has stood down, or they arrest with no help on the horizon beyond a mortician who will come, with no particular sense of urgency, and more or less pack the patient’s head in ice.7 Cryopatients routinely experience many minutes or even hours of ischemia, not only absent cardiopulmonary support, but absent even cooling of any kind. In one CI case a few years ago, a patient went for 4-hours after a witnessed and expected cardiac arrest with no ice, or other refrigerant applied to her head! This story is in no way remarkable except that in this case, both the patient and her spouse (attending her) were committed, signed up cryonicists! How could this happen?

The answer is that it happened because of lack of information, lack of education, lack of preparation, and the complete absence of even the most basic tools to cope with an emergency that was not just a remote possibility, but an absolute certainty, given that the patient was actively dying. Over the past few years, people in medicine (outside of cryonics) who have read some of these case reports online have remarked to me, “What is the matter with these people? Are they stupid, or do they just not care?” Perhaps Benjamin Franklin comes closer to the truth with his observation that “the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.” Are we cryonicists stupid, insane, or are we just not paying attention?

Figure 10: The Polycom Practitioner Cart HDX series enables medical professionals to provide patients access to care regardless where they are located. Featuring the full range of HD resolutions, including 1080p and 720p at 30 frames per second (fps) and broadcast quality 720p at 60 fps.. This is an example of the kind of technology being employed medicine today. While certainly advanced, it is no longer considered cutting edge, and devices such as the ‘Practitioner’ are now routinely commercially available items. 8

Figure 10: The Polycom Practitioner Cart HDX series enables medical professionals to provide patients access to care regardless where they are located. Featuring the full range of HD resolutions, including 1080p and 720p at 30 frames per second (fps) and broadcast quality 720p at 60 fps.. This is an example of the kind of technology being employed medicine today. While certainly advanced, it is no longer considered cutting edge, and devices such as the ‘Practitioner’ are now routinely commercially available items. 8

For over two decades now, egregious errors in the stabilization and cryoprotective perfusion of patients have been occurring and they have increased both in severity and frequency. Most of these errors are have been due to an inadequate knowledge base and also as a result of inadequate supervision of staff. Both of these deficiencies could be at least partially addressed by the presence of skilled personnel in the field, or in the operating room, who cannot be physically present for the procedure. In the past, the managements of cryonics organizations have categorically refused to consider the use of virtual, or Telepresence consultants to assist in remedying this problem – as well as in improving data capture and documentation.

This behavior is hard to understand, given that cryonicists are disproportionately computer scientists, programmers and engineers with, ostensibly, an excellent understanding of the technological capabilities now available for high bandwidth data transmission over the web. In an era of Skype, high quality webcams for less than $40, and increasingly universal web access, why aren’t cryonics organizations using this technology?

I have participated in two human cryopreservation case via Skype, and, at least from my perspective, I believe I made a material difference in both patients’ care. With a moderate amount of effort, a reservoir of medical and technical consultants could be assembled to assist with cases in real time – and to provide specialized information in unusual circumstances. What I am proposing here is the creation of a real-time, web-based oversight and supervisory group . Also on that oversight group, in my opinion, should be at least one knowledgeable and assertive Alcor member who is not present in a formal technical capacity. It’s astonishing how often someone who does not have extensive training in cryonics, medicine, or related areas is the first one to spot a problem.

Figure 11: Consultants, both paid and volunteer, should monitor every part of the cryopreservation procedure using broadband transmission of data, and Telepresence via Skype, or other videophone or videoconferencing providers.

Figure 11: Consultants, both paid and volunteer, should monitor every part of the cryopreservation procedure using broadband transmission of data, and Telepresence via Skype, or other videophone or videoconferencing providers.

To repeat, at a minimum, one powerful way to ensure improved performance in cryopatient care is to constitute an oversight team of medical professionals and others with relevant expertise, to oversee each case in real time. This should be supplemented with high quality fixed and floating videography of all cases – videography that will be reviewed by the oversight team, along with all of the case data.

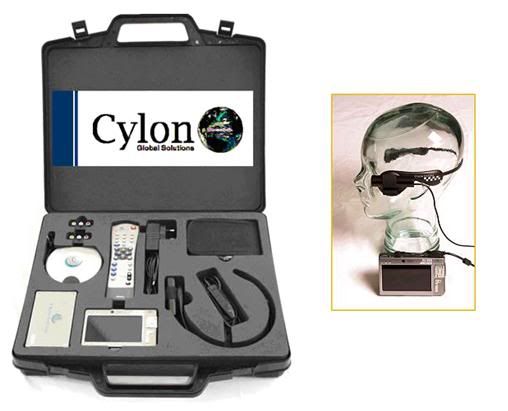

The advent of compact, reliable and wearable video recording equipment that can be deployed on the persons of stabilization Team members, as well as the ready and affordable availability of continuous, forensically certifiable, digital video recording equipment (with the capability of uninterrupted recording of 2-weeks of ~250 to 450 frame per second high quality color video (each terabyte of memory now costs approximately $400.00) have also not been exploited by cryonics organizations‡).

Figure 12: Cylon Body Worn Surveillance System. Wearable DVR: 16 x 9 screen size 720 x 576, resolution 4”, display video playback – MPEG-4 SP with stereo sound. Near DVD quality up to 720×480 @ 30 f/s (NTSC), 720×576 @ 25 f/s (PAL), AVI file format. WMV9 up to 352×288 @ 30 f/s, and 800 KBit/s. Exview Camera: Instant auto focus, Hi Resolution – 1 Lux 2 CIF image, rugged, waterproof, heat resistant and can be integrated into helmets and headwear. (Photos courtesy of The Audax Group, Plymouth, South Devon, UK, http://www.audaxuk.com/cylon/index.htm)

Figure 12: Cylon Body Worn Surveillance System. Wearable DVR: 16 x 9 screen size 720 x 576, resolution 4”, display video playback – MPEG-4 SP with stereo sound. Near DVD quality up to 720×480 @ 30 f/s (NTSC), 720×576 @ 25 f/s (PAL), AVI file format. WMV9 up to 352×288 @ 30 f/s, and 800 KBit/s. Exview Camera: Instant auto focus, Hi Resolution – 1 Lux 2 CIF image, rugged, waterproof, heat resistant and can be integrated into helmets and headwear. (Photos courtesy of The Audax Group, Plymouth, South Devon, UK, http://www.audaxuk.com/cylon/index.htm)

High capacity digital video recorders which allow for fast and easy data searches, provide self-schedule management, automatic data backup, e-mail event alert, and offer IP Address Dispatch (for use with dynamic IP), and control of multiple systems from a remote location9 are now in wide use in law enforcement, government and business. In-house and in-field (mobile) versions of forensic video systems are rapidly becoming the standard of practice for law enforcement where they are used to protect police officers against accusations of abuse or misconduct.10,11

One example, widely used by law enforcement around the world is the Cylon Body Worn Surveillance System (Figure 12). The unit consists of a compact, waterproof DVR, and a high resolution color camera (worn on a headset) as shown in Figure 4, above. The DVR can store 400 hours of Mpeg-4 quality full color video and audio recording on it 100 GB hard drive and has a battery life of ~12-hours at its peak, 30 fps recording rate. Since the unit is built for law enforcement, it has time/date stamping and event marking capability as well as sophisticated graphical user interface software which allows for rapid search and retrieval of recorded material

Figure 13: Smartphone displaying the complete, real-time streaming data-set from a patient in the Intensive Care Unit to his physician – who can be anywhere he can get a signal. Just like the TV ads says – “There’s an App for that!”

Figure 13: Smartphone displaying the complete, real-time streaming data-set from a patient in the Intensive Care Unit to his physician – who can be anywhere he can get a signal. Just like the TV ads says – “There’s an App for that!”

It is more than a little bizarre (and ironic) that cryonics organizations, largely comprised of and operated by technophiles focused on the leading edge of information technology, have failed to adopt these advances, whilst governments, the military and law enforcement agencies have rushed to embrace them in their earliest implementations. How is it possible that physicians, one of the more conservative of the professions, are using Smartphone technology to monitor their patient’s in ICU (including their vital signs, ECG, mean arterial pressure, central venous pressure, oxygen saturation, and just about any other parameter that can be hooked to the web), and cryonicists are not? And why is it possible for me to log on to my computer in Ash Fork, AZ and watch Piccadilly Circus in London, or the ongoing construction of the Olympic Complex in London, in real time, but not be able to see how my friends, loved ones, and former fellow Alcor members (now patients) are being cared for?

If we seriously plan to live in the future, we’d best learn to do so as it arrives, because as it stands now, at least in terms of patient care transparency, and feedback generation, the future for us, was yesterday.

Footnotes:

[1] CIPA patients have a defect in th e voltage gasted sodium channel SCN9A (NaV1.7). Patients with such mutations are congenitally insensitive to pain and lack other neuropathies. There are three mutations in SCN9A: W897X, located in the P-loop of domain 2; I767X, located in the S2 segment of domain 2; and S459X, located in the linker region between domains 1 and 2. This results in a truncated non-functional protein. NaV1.7 channels are expressed at high levels in nociceptive neurons of the doral root ganglia As these channels are likely involved in the formation and propagation of action potentials in such neurons, it is expected that a loss of function mutation in SCN9A will lead to abolished nociceptive pain propagation.

[2] Clearly, in addition cameras, there needs to be intrusion protection with the patients care space being accessible only by a coded entry system (cards or numbers) .

‡ An upend example is the Toshiba EVR RAID-5 (redundant backup system) 32 channels DVR 480 fps (15 fps per cam) security video recorder which can accommodate up to 4 terabytes of memory and retails (1 terabyte) for just under $6,000. Such a system would allow continuous video surveillance of every room of a large residence with 6-weeks of audio-video storage capacity.

References

1) Darwin, M. The myth of the golden scalpel. Cryonics. 7(1);15-18:1986, p http://www.alcor.org/Library/html/MythOfTheGoldenScalpel.html. Retrieved 2010-08-31. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

2) Dawin, M. On technology. Message-Number: 3088 posted to CryoNet on 09 Sep 94 00:54:02 EDT: http://www.cryonet.org/cgi-bin/dsp.cgi?msg=3088. Retrieved 2010-08-31

3) Darwin, M. Quality control and cryonics. Message-Number, 17803: posted to CryoNet on Mon, 22 Oct 2001 01:19:44 EDT: http://www.cryonet.org/cgi-bin/dsp.cgi?msg=17803. Retrieved 2010-08-31

4) http://www.cryonet.org/cgi-bin/dsp.cgi?msg=1148

5) Johnson, L, Baldyga , S. Frozen: My Journey into the World of Cryonics, Deception, and Death. ISBN 9781593155605, Vanguard Press (October 6, 2009).

6) http://www.urbaneye.net/results/ue_wp6.pdf.

7) http://www.alcor.org/Library/html/casesummary1831.html, http://www.alcor.org/Library/html/casesummary2340.html, http://www.alcor.org/Library/html/casesummary1356.html

8) http://reseller.tmcnet.com/topics/sip-endpoints/articles/53990-polycom-enabling-collaboration.htm.

9) Toshiba EVR Series Security DVR With 4 Terabytes of Memory. Toshiba America Information Systems, Inc., 2006. (Accessed at http://www.mp50.com/8070/DVRUPG1RT525TR5.asp.)

10) Castro H. Police cars get digital cameras; Seattle department first to use new wireless capability. In: Seattle Post-Intelligencer Reporter; 2004.

11) Digital video recorders give more reliable, accurate footage to police. The Enquirer. (Accessed September 8, 2007, at http://www.policeone.com/police-products/vehicle-equipment/in-car-video/articles/99438/.)

12) Cylon Body Worn Surveillance System. Audax Group, 2007. (Accessed September 9, 2007, at http://www.intelcam.co.uk/.)

“We are already at a point where our enemies have used these advances in imaging and computing technology against us: isn’t it time we started using them to our advantage?”

Is any enemy to you anyone who disagrees with the value of saving lives through cryonics and wants to stop you (and as a result, commit the equivalent of involuntary manslaughter?)

I like reading your blog in part because I am curious about Robin Hansons statement that cryonics has at least a5% chance of working. Hanson is really really bright so I am following up on his belief that cryonics has validity and I don’t want this need for clarification to cause any kind of suspicion or disregard for facts.

I signed a form as a witness to enroll an acquaintance’s child into cryonics. It was a few years ago and I am not familiar with the legal aspects of this. But my whole point is that statements language begs for clarification. I am sure you will get around to it in other blog posts because you are quite passionate about this subject.

That’s a damn good question, and I thank you for asking it. My threshold for what constitutes an ‘enemy’ of cryonics is considerably higher than, “anyone who disagrees with the value of saving lives through cryonics and wants to stop it.” I’ll tell you what to me is a fascinating thing. Some of the people who really loathe cryonics, and who have spoken out it against it publicly and credibly (the latter because of their professional credentials in science, medicine or ethics) have privately done more to help cryonics than have many cryonicists. To be specific, they have answered my (and others’) technical inquiries in detail, spent considerable time, and even some money, providing me with unpublished data, and in a couple cases, even called to provide specific technical advice bearing on cryopatient care. I’m not sure exactly why men like this do these things, but one told me that it was because, while he thought cryonics a very bad thing, if it was going to be done, then the way we were doing it (at that time) was the right way – meaning that we were creating new knowledge by observing, and learning from what we were doing. I’ve pasted in a few of the more direct instances of what I think this physician/scientist meant when he made that remark, at the end of this response. You can judge for yourself.

I believe that another material factor in this attitude, and the positive behavior it generated, was that it was apparent that both my colleagues and I genuinely believed not only in what we were doing vis a vis cryonics, but that we also believed that it was a good and moral thing to do.

To answer your question more directly and succinctly: an enemy is someone who has made it their task not merely to disagree, but to systematically, and employing the tactics of warfare, attack cryonics and its practitioners. What are the tactics of warfare? They are the systematic use of force and/or fraud against your opponent. Just because someone thinks cryonics is a bad idea, says so, and mocks or criticizes it publicly, doesn’t make them an enemy. Rather, they are just one of probably billions of people who disagree with our position – or who even think cryonics is bad or evil, and should be stopped. While I was raised a Roman Catholic, and the Jesuits had their time with (and influence) on me, I do not believe that ‘impure thoughts’ :-) are sins equivalent to deeds. Nor do I believe that a man who has murder in heart and on his mind, day and night for 20 years, is a murderer. You can hate cryonics, you can speak out reasonably against its practice, and that does not make you an enemy.

When you cross the line into actions employing tactics like theft, slander, libel, false police reports, gross ethical violations of medical confidentiality and personal privacy – THEN you’ve become an enemy. Those are the tactics of both disturbed individuals, and of warfare. In war, anything goes, unless the parties involved set and keep to agreed limits. The various proxy wars between the US and the USSR during the Cold War are the best examples that to come mind of this; both had thermonuclear weapons, and yet both carefully prosecuted wars with each other with the tacit understanding that they were not going to use them.

Do I believe that war is ever justified? Yes, of course I do. It would be impossible to propose to survive for more than a very brief period of time (hours, days, weeks?) without being willing to prosecute a war. And people who believe otherwise are merely shifting the burden of fighting and dying onto others, who, willingly or otherwise, do it for them. Any clear-eyed look at the natural world will confirm that reality: plants are especially vicious if you watch them on time lapse photography, or can sense their biochemical attacks on each other.

Having said that, I prefer to avoid it at almost all costs – but not at all costs. I think it likely that this current (and unprecedented) round of truly vicious attacks on cryonics, and on cryonics patients, is in part due to a lack of understanding of just how important cryonics is to us. In part, that’s our fault, but it still does not excuse the attacks.

I have no idea of what the chances are of cryonics ‘working’ largely because there are different, interacting elements that will determine its probability of success. From a purely biophysical standpoint, there are the issues of whether sufficient information remains in the cryopreserved corpus to allows for recovery of the individual, and whether it is physically possible to access, manipulate, and then configure that data into a functioning person? If those things are answered in the affirmative, there are then myriad other issues, such as whether it is socially, politically or practically possible to recover the cryopreserved person. If it is economically impossible, it is illegal, or if technological civilization is interrupted, or ends – well, these are a different set of considerations.

About the biophysical, we can do nothing – at least not for those already cryopreserved- what will be will be – that’s the uncontrollable part of the equation. However, for people not yet cryopreserved, we have both the opportunity and the obligation to improve the odds until the biophysical part of the probability ‘calculation’ is no longer in play, but has become a certainty. As to the social, political and legal factors affecting the probability of the outcome, well, there the system is considerably more elastic, in theory. I once believed that it might be possible to carry out our business without perturbing the ‘macro-system’ we are embedded in. I tried that approach for 40 years. It won’t work.

One (of many) reason it won’t work is interesting, and it has to do with an emergent property of technological advance that I have, for many years, referred to as the “species survival veto number.” That’s the number of individual humans it takes to make a decision that will end technological civilization – or even the species. Until the advent of thermonuclear weapons, that number was very, very large – so large that the issue did not merit either consideration, or discussion. Even in a place as small as Jonestown, some people weren’t going to drink the Koolaid, period. The advent of thermonuclear weapons dropped the veto number to a disturbingly low number – perhaps a few hundred individuals. Very shortly it will get smaller still, perhaps dropping to 1 at some point.

It’s apparent on the face of it, that neither children, criminals or psychopaths can be allowed to wield volatile lethal force. In the case of children, we separate them from such resources and we supervise them. We do the same with criminals (who are in fact, mostly psychopaths) and we go further by incarcerating them. Children grow to maturity, and can be educated and mentored, and psychopaths can presumably be treated or cured, with more sophisticated technology than we currently have at our disposal. But in the meantime, we don’t let them play with guns, or have control of nuclear weapons.

The history of revolutions – both ideological/political, as well as the history of technological advance, speaks powerfully to the criticality of leverage. As my friend and mentor Curtis Henderson often used to say, “The Russian revolution consisted of two men, a dog and a printing press.” An exaggeration, but not far off the mark. Today, I would point to Tunisia and Egypt, and then say this: Wikileaks and Social Networking technology (including the mobile phone). When I was in Cairo in 2000 and 2001, I used to walk through Tahrir Square almost every day, and I knew the people and the place very well. I would have laughed at you if you had told me that what has just happened there, so far, was possible (regardless of how it turns out – and personally, I think the odds favor a bad long term outcome due to global economic problems). That’s leverage! On the dark side, consider the attacks of 9-11. I should be surprised if the dollar amount of the cost exceeded $1 million – for the attackers, that is. But my bet would be that the cost to the US and the West has been in the range of a trillion dollars – and that’s without scoring a single definitive victory in retaliation. Now, that’s really leverage! And that leaves out the socio-political havoc and long term damaging consequences of the enormous extra burden of regulation (not to mention lost time and inconvenience) that resulted. Plus, and this not trivial, there is almost nothing more satisfying than making your enemy behave like an idiot. All I will say on that subject, is that you would have to spend some serious time in the Arab world to appreciate the delicious irony of forcing all those Western men to have to take their shoes off and be groped by security screeners – some of whom are women!

I should have seen this coming years ago, when I returned from India, and remarked with wonder that even most of the lepers had mobile phones! They may be untouchable, but they cans still be useful – providing they have a phone!

Thus, my ambitions are humble, namely to leverage the values we hold sacrosanct into a controlling position over this civilization. You may begin laughing now, but while you do, consider Lenin, and consider Cairo.

And, its not like we have any choice. – Mike Darwin

Leaf, JD, Darwin, M, Hixon, H. A mannitol-based perfusate for reversible 5-hour asanguineous ultraprofound hypothermia in canines: http://www.alcor.org/Library/html/tbwcanine.html

Darwin, M. Report on the use of the Cordis-Dow hollow fiber dialyzer as a membrane oxygenator in profound hypothermia. Cryonics. 4(9);3-5:1983: http://www.alcor.org/cryonics/cryonics8309.txt

Leaf, JD, Federowicz, M, Hixon, H. Hemodialyzers as experimental hollow fiber oxygenators for biological research: a preliminary report. Cryonics. 5(5);10-19:1984: http://www.alcor.org/cryonics/cryonics8405.txt

Darwin, M, Hixon, H. Evaluation of heat exchange media for use in human cryonic suspensions. Cryonics. 5(7);17-36:1984 http://www.alcor.org/cryonics/cryonics8407.txt

Darwin, M. Post mortem results: some perspectives. Cryonics. 5(9);1-4:1984: http://www.alcor.org/cryonics/cryonics8409.txt

Darwin, MG. Cryopreservation case report: Arlene Francis Fried, A-1049: http://www.alcor.org/Library/html/fried.html

Federowicz, M, et al. Treatment or prevention of anoxic or ischemic brain injury with melatonin-containing compositions. United States Patent 5,700,828 filed December 7, 1995, issued December 23, 1997: http://patft.uspto.gov/netacgi/nph-Parser?Sect1=PTO2&Sect2=HITOFF&u=%2Fnetahtml%2FPTO%2Fsearch-adv.htm&r=18&f=G&l=50&d=PTXT&p=1&p=1&S1=5,700,828&OS=5,700,828&RS=5,700,828

Federowicz , et al. Mixed-mode liquid ventilation gas and heat exchange. United States Patent 6,694,977 filed : April 5, 2000, issued February 24, 2004: http://patft.uspto.gov/netacgi/nph-Parser?Sect1=PTO2&Sect2=HITOFF&p=1&u=%2Fnetahtml%2FPTO%2Fsearch-bool.html&r=5&f=G&l=50&co1=AND&d=PTXT&s1=6,694,977&OS=6,694,977&RS=6,694,977

Harris, SB, et al. Rapid (0.5°C/min) minimally invasive induction of hypothermia using cold perfluorochemical lung lavage in dogs. Resuscitation. 50; 189–204:2001: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11719148

> each terabyte of memory now costs approximately $400.00

More like $40 since 2TB goes for $80: http://forre.st/storage#sata

Yes, that’s right, and it speaks to the breathtaking and breakneck speed of technological advance in electronics and computing. You see, that section of my piece was actually cut and pasted from a series of articles I wrote several years ago, entitled, “Last Aid as First Aid for Cryonicists.” I couldn’t get either Alcor or CI to publish it, and even Danila Medvedev, in Russia, didn’t seem interested. So, its been sitting on the hard drive unused. I never even thought to recheck the cost of memory! Thanks for the correction. – Mike Darwin

Wow!

Thanks for that very thorough reply. My reservations about reading your website are basically cleared up now. I agree far more than I disagree with your viewpoint, to the extent that I really understand it.

Where do you get the time to write so profusely? I am a student at UTD and work part time.

Anyway, I am primarily interested in the biophysics of personality, consciousness and qualia (at an amateur level – and who isn’t at this stage?!). Anyway, I really want to continue reading your website and look into the science of subjective experience and its restoration with increasing precision.

I believe the other part of the equation — having someone around that wants to restore you — is the most uncertain part, so I don’t have a clue why Hanson believes it’s 5%! He is a fan of bayes…

There is still a huge gap in our knowledge. And sadly, what matters far more right now (for me) is money, not knowledge. But I will bookmark your site and continue to read. Thanks!

Thanks for your remarks. I’d be interested to hear what your opinion is about the likelihood of personal identity surviving cryopreservation – and what you think are the biophysical structures (and/or chemistry) that encode it in the brain?

As to having someone around who wants to restore you decades hence, well, best not to leave that to chance. In fact, it’s pretty much impossible to leave to chance because of the quirk of the preservation process we’re using, namely that it requires a lot of vigilance and effort in addition to the countless and continuous input of joules of energy in the form of LN2. If it were possible to simply shut a patient away in some presumably safe and remote place, then this would be less of a concern. But, as it is, the job of keeping things going is on each of us, and on each of those who will come after us. It a dynamic process from start to finish – or it fails.

And tank time is risk time. That’s something I think is largely lost on most cryonicists. They see just GETTING cryopreserved as the equivalent of having made it to heaven. Arguably, that’s the easy part, and the hard part may be staying cryopreserved long enough. Recently, a longtime cryonicist named Brook Norton, has created a “cryonics calculator” http://www.cryonicscalculator.com which allows you to input the chances of various things going wrong over a given period of time, and then calculates your chances of surviving. At first glance, it seems just a toy, another Internet distraction to waste time, or to amuse. It features some unlikely risks, such as fire, because most industrial buildings are sprinklered – and that is an incredibly effective defense against fire. But, regardless of what risks are on the spreadsheet as it is, you can always plug your own risk set in. The (to me)unexpectedly valuable thing about this tool is that it demonstrates rigorously what I’ve long suffered great angst over intuitively, and that is that your time under refrigeration must either be brief – less than a century or so – or your risks had better be very, very, very small. Otherwise, you don’t make it. Cumulative risk is every bit as powerful as cumulative interest… So, this a useful tool to help people decide just how important it is to them to improve the quality of human cryopreservation techniques. — Mike Darwin