The following is an edited for publication version of a letter that has been written in various versions to various people over the past 5 years. This, the last version, was written in 2008. These letters always began Dear _________, with the name of nascent group or company where the blank space is. In re-reading this letter I am reminded a bit, and whimsically, of St. Paul’s letters to various aspiring small groups of Christians, geographically remote from each other, and yet in search of community and competence in their mission. Hence the title here, “Letter to the Aspirants.”

– Mike Darwin

My comments have been invited about you efforts to establish a new cryonics organization, and I hope that they will not be unwelcome, and indeed, that they will be of genuine benefit to all of you.

I would like to start by saying that you are all to be commended for deciding to take action to improve your situation and to make reliable and hopefully reasonably high quality cryopreservation services available in your country. The very acts of seeing the need for this, and then taking the decision to proceed, are rare achievements in and of themselves. Congratulations!

What I have to say to next is likely to be misunderstood, and all I can hope for is that you realize that my perspective is born of over four decades of hard won experience; much of it bad. I have neither interest in, nor prospects for involvement in involvement in your undertaking, so what I have to say here is said free from any conflicts of interest, or taint of personal ambition.

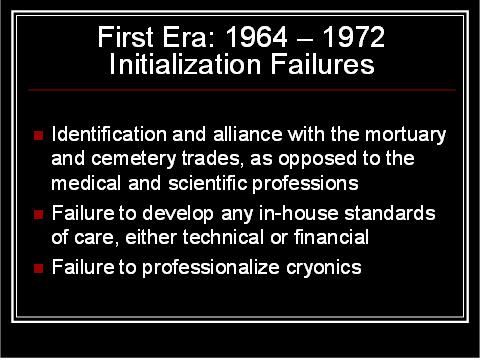

In reviewing the thousands of documents that chronicle the birth of cryonics in the United States (US), I have come to realize that a number of critical and potentially avoidable errors were made which doomed all of the first cryonics organizations to failure, and severely damaged the credibility and viability of cryonics in the US and, to some extent, in the rest of the Western World. I believe it is possible to learn from these mistakes and to not repeat them.

I am not going to go into the underlying cultural and social reasons that complicated the attempted launch of cryonics in 1964 in the US here. They are critically important and I urge you to understand them, because they still largely apply, and they will impact your efforts much as they did in 1964. Suffice it to say here and now, that if you want to have any hope of launching a controversial and socially destabilizing new enterprise that will certainly encounter resistance and hostility, you absolutely must have solid planning,. and near complete mastery of the practical aspects of the operation, before you launch.

I think it helps to think of starting a cryonics operation in the same terms as if you were starting any other high technology enterprise that requires substantial physical infrastructure and wide-ranging expertise in both hands-on and theoretical areas. If you were planning on launching a stem cell treatment clinic, or a small scale custom biochemical synthesis operation, you would be facing a far, far easier task than starting a cryonics operation.

For one thing, you would have the luxury of failing with these enterprises, repeatedly if necessary; and that is not a luxury you will enjoy with cryonics. And certainly not after you have your first patients in storage. Failure carries with it likely catastrophic consequences, not just for your particular undertaking, but for cryonics in the world in general. You have only to look at the sorry situation in France today, to have an example of how mishandling the launch of cryonics can cause devastating and lasting prohibitions. The escapades of Anatole Doilinoff and Rene’ Martinot, coupled with the adverse experience of Chatsworth in the US, were all it took to make cryonics practically impossible in France for the last decade.

From a practical standpoint, what went wrong with the launch of cryonics in the US was that there were no skilled experts in cryonics, and the people launching the first cryonics organizations did not realize that they first and foremost needed to become experts themselves (to the extent that that was possible), before attempting to ‘sell’ cryonics to the public, or even to sell it to other cryonicists.

I assume that none of you would presume to start a stem cell clinic, or carry out small batch biochemical synthesis without first mastering these areas, or hiring the relevant experts. To just leap into it and ‘learn as you go’ would be a disaster and, in a world of regulations and controls, would lead to punishment, or other sanctions. Maim, injure or kill people through incompetence with chemistry or medicine, and you will end up in a great deal of trouble – at least in the West, today.

The same is true of cryonics. It was true in 1964 and it is true today. The difference is that 45 years have elapsed since 1964 and there are now experts, and substantial bodies of expertise in almost every area of cryonics. The problem is that few cryonicists recognize this, or even recognize the need for such expertise, or often that such expertise even exists! Indeed, both CI and Alcor operate with huge holes in these areas, and only remain in business because they do have expertise in the one area of cryonics operations which provides unequivocal feedback, and in which it is absolutely unacceptable (i.e., lethal) to fail: long term cryogenic care.

Sadly, most people who currently run cryonics organizations, or who aspire to operate them, actually believe they are experts in the biomedical aspects of cryonics and that their organizations represent the current practical limits of the state of the art. Depending upon what level of preservation you consider acceptable, they may arguably be right. However, if an objective standard, based on what is currently cryobiologically and medically possible (and practical) is used as the reference, then they are all woeful failures.

There was a time in cryonics (1981 to 1995) when every Alcor or CryoCare patient who could benefit from it received immediate and effective post-arrest cardiopulmonary support, prompt blood washout, and thorough and complication (iatrogenesis) free cryoprotective perfusion. The limiting factor on the ‘quality’ of the resultant preservation was not post-arrest ischemia, but rather was peri-mortem pathology and ischemia and, most importantly, cryoinjury due to freezing. Alcor (and later CryoCare) had reached the point where, under good conditions (i.e., the slowly dying patient with an intact brain) the only limit on viability after cryopreservation was cryoinjury. By now, it should have been the case that most patients presenting for cryopreservation with advanced notice (about 1/3rd of all cryopatients) should be suffering only biochemical injury from cryoprotectant agent (CPA) toxicity, minor mechanical injury from osmotic stress (primarily in the brain) and limited fracturing damage if intermediate temperature storage (ITS) was used in place of liquid nitrogen storage. Instead, it is now the case that ischemic injury and long post-arrest delays constitute the biggest source of injury; and very likely typically preclude vitrification. It is virtually impossible to achieve CPA equilibration in patients with significant warm and cold ischemic injury. In my opinion, this is a terrible tragedy that has compromised advancing the credibility of cryonics within medicine, and within our society at large. It has also caused intense demoralization within the ranks of activist cryonicists in the US; no one feels good about grossly injurious, often sloppy, and always amateurish (and incompetent) patient stabilizations and perfusions.

So, my injunction here is simple and absolute: become competent at offering whatever level of cryopreservation technology you decide is necessary or acceptable before you commence public operations. Yes, you may have to cryopreserve some of your own under haphazard conditions, but this should be a temporary situation, and should not include the public (or last-minute, “at-need” non-member cases). Get core competence before you commence commercial operations.

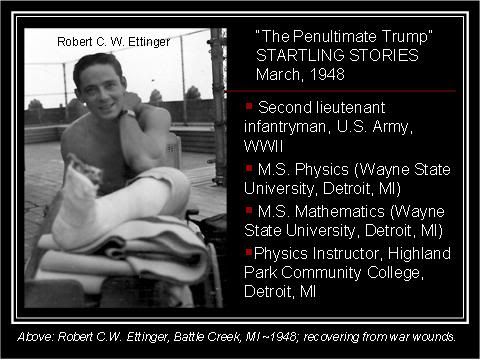

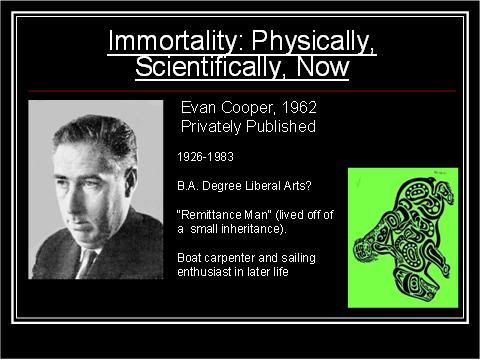

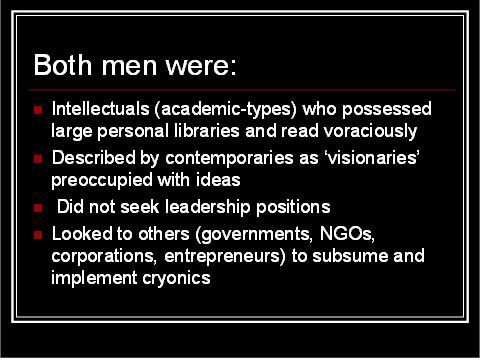

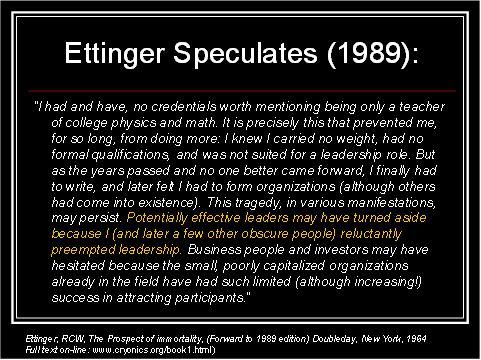

It may help to review what went wrong and what went right in the launch of US cryonics. The first problem was that both Ev Cooper and Robert Ettinger were idealistic ‘dreamer types’ with little practical experience in any hands-on endeavour. This not meant to be a disparaging remark. Clearly, they were ideally suited to conceiving the idea of cryonics and it was not for lack of trying that they were unable to find the “right” people to help them execute it:

Both men were introverts:

The character of these two men and the ‘outrageous’ nature of cryonics, more or less precluded the kind of careful planning required to launch such a complex, controversial and failure intolerant idea, and its associated enterprises.

The character of these two men and the ‘outrageous’ nature of cryonics, more or less precluded the kind of careful planning required to launch such a complex, controversial and failure intolerant idea, and its associated enterprises.

In short, there was a failure to take personal responsibility for the success or failure of implementing cryonics and a near total failure to understand the enormous negative impact of missteps, or outright failure, on the credibility and viability of the idea.

In short, there was a failure to take personal responsibility for the success or failure of implementing cryonics and a near total failure to understand the enormous negative impact of missteps, or outright failure, on the credibility and viability of the idea.

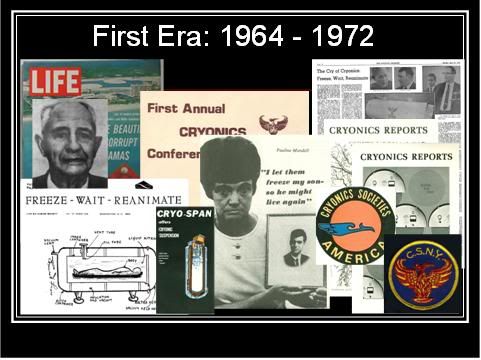

Cryonics was ‘launched’ on a ‘make it up as you go along basis’ with essentially no concern for the cost of private, let alone highly public failures. Everything was done in front of the media. and much of what was done, including how patients were stored, was driven by a desire to attract and hold the interest of the media in the mistaken belief that publicity would lead to rapid success and acceptance.

Lots of money went into appealing promotional materials, when there was in fact nothing of substance to promote and, in the case of the Cryonics Society of California, nothing at all to promote!

There was a complete lack of even ‘first-cut’ armchair business plan-style planning.

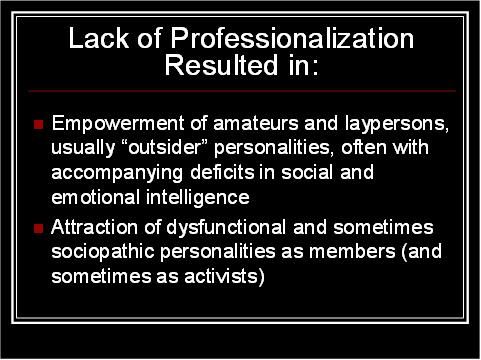

This lack of planning and anticipation of the basic technological requirements to deliver a responsible service lead to what can only be described as a grotesque lack of professionalism:

In fact, Robert Ettinger himself has remarked on this:

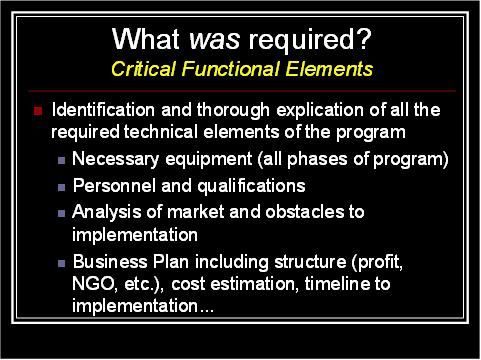

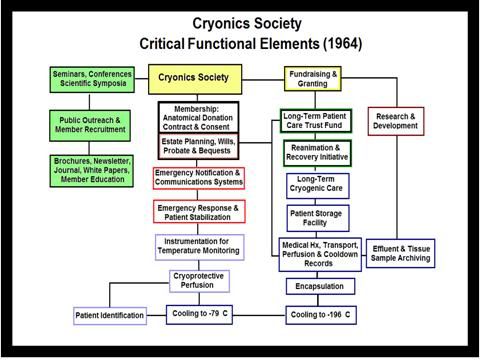

What was really required was sound, detailed planning, and I can give you a concrete example of what this should have looked like. I know it was possible because it was done 8 years after cryonics was launched and with less available resources than were present when cryonics was initialized between 1964-1968.

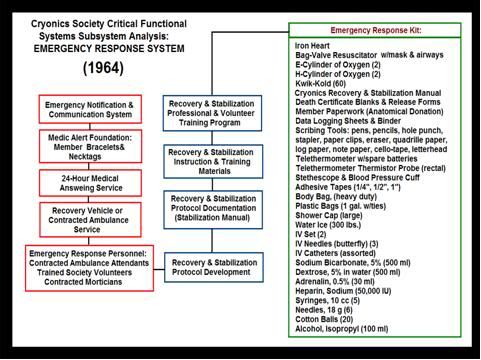

Space and time do not permit detailing every aspect of the planning that should have been put into place, so I’ll use one element of what was needed as an example. In this case, I’ll use the emergency response and stabilization system, as it should have been planned and prepared for prior to the launch of the first cryonics operations in 1967-8:

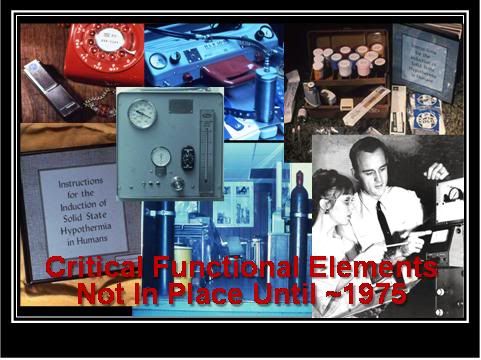

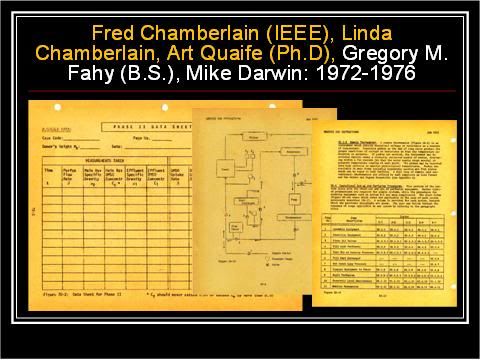

That such planning was possible, and that it would have resulted in a basically competent and viable operation, was demonstrated in 1972 by Fred & Linda Chamberlain. While they made mistakes, they mostly ‘got it right.’ They started out by seeking out and employing experts where they had to, and by mastering, with hands on experience, every type of technology essential to cryonics that was required.

They established a working emergency response system from scratch including bracelets, pagers, and the communication system and its allied written standard operating procedures and data collection forms. They purchased and learned to reliably use a mechanical cardiopulmonary resuscitator and airway management and ventilation equipment. It took us dozens of hours in countless practice sessions to become proficient with this equipment. I know this because I joined them in this effort in 1974.

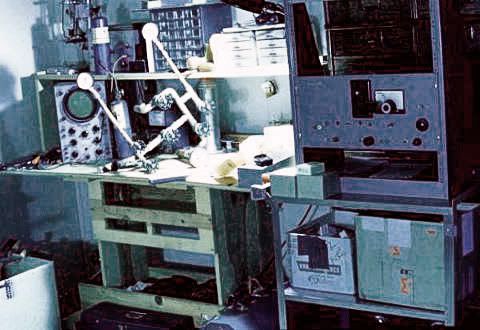

We built perfusion equipment and we tested it in the wet lab under static conditions and with animals. Below is a photo of the prototyping lab that was set up in the back bedroom of the Chamberlains’ home in La Crescenta, CA circa 1973:

Second generation perfusion machine, perfusate reservoir, and heat exchanger in its first use on a cryopatient:

Second generation perfusion machine, perfusate reservoir, and heat exchanger in its first use on a cryopatient:

We determined, in advance and in consultation with experts, the procedures with which we were going to cryopreserve our patients, including standards for monitoring of the process and data collection and documentation:

Every aspect of the operation, business, financial, promotional and technical were planned in advance. In many cases our plans did not long survive contact with reality, but the very act and discipline of planning allowed us to quickly learn, and to document and build upon experiences, both good and bad.

We constructed a mobile operating room to carry out perfusion and built and tested cool down equipment. We started with an old second-hand laundry lorry and transformed it into a credible perfusion room:

We acquired cryogenic storage equipment and familiarized ourselves with every aspect of its safe operation and the safe handling of liquid nitrogen. We did this first by didactic study and then followed-up the book-learning with careful, incremental, hands-on experience.

We acquired cryogenic storage equipment and familiarized ourselves with every aspect of its safe operation and the safe handling of liquid nitrogen. We did this first by didactic study and then followed-up the book-learning with careful, incremental, hands-on experience.

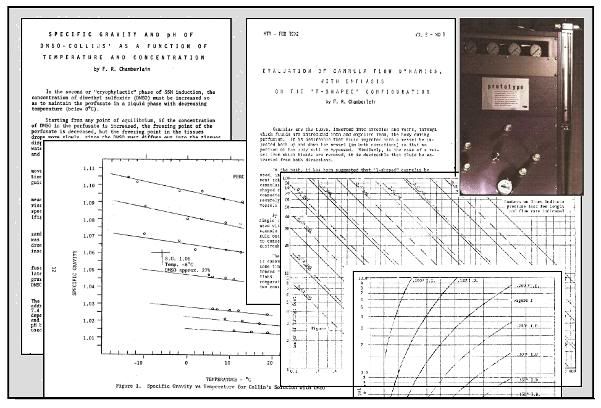

During this time we were documenting what we learned and what we proposed to do in a variety of publications:

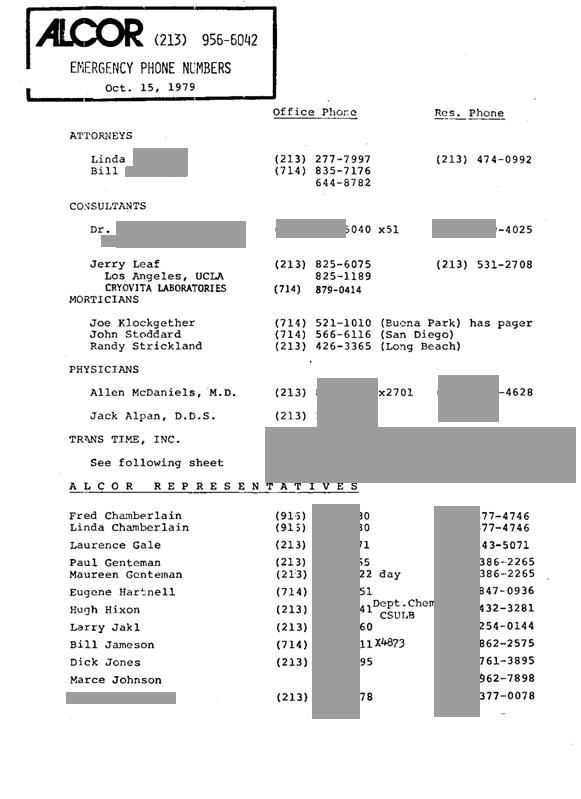

Below is an emergency contact list (ECL) (redacted for privacy) from 1979; the oldest I have scanned in at this time.

These lists were updated no less frequently than quarterly by Linda Chamberlain, and they were maintained current in an era when there were no personal computers and at a time when these lists had to be typed by hand, and then mailed out via snail mail to all the Alcor Representatives. Beyond these technological handicaps, there was the fact that the people running Alcor had demanding full time jobs. From the period of 1972 to 1976 not only was the ECL maintained and distributed without fail by three people holding full time jobs, these same three individuals also:

These lists were updated no less frequently than quarterly by Linda Chamberlain, and they were maintained current in an era when there were no personal computers and at a time when these lists had to be typed by hand, and then mailed out via snail mail to all the Alcor Representatives. Beyond these technological handicaps, there was the fact that the people running Alcor had demanding full time jobs. From the period of 1972 to 1976 not only was the ECL maintained and distributed without fail by three people holding full time jobs, these same three individuals also:

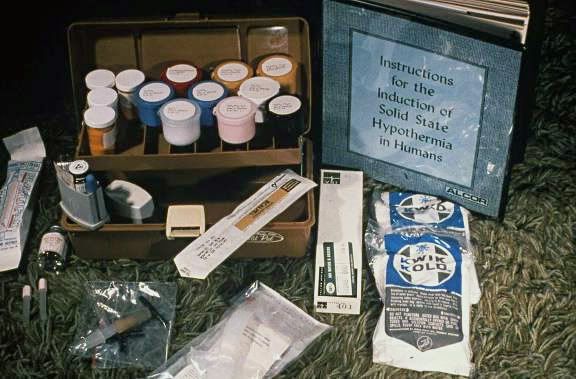

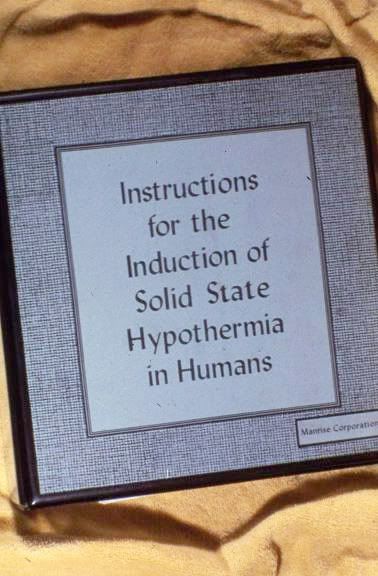

• Wrote the first procedure manual for human cryopreservation and assembled the first emergency response kit:

• Produced a wide range of brochures and literature as well as produced a monthly newsletter (2 pages 8.5” x 14”) during much of that interval.

• Produced a wide range of brochures and literature as well as produced a monthly newsletter (2 pages 8.5” x 14”) during much of that interval.

• Conducted fundamental cryonics research:

• Corresponded extensively (using a typewriter):

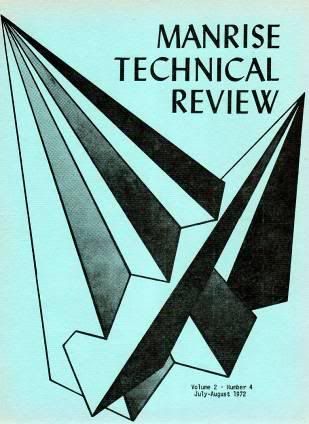

• Edited a sophisticated technical magazine (Manrise Technical Review). It is also worth mentioning that the graphics reproduced above were drawn by hand by both Fred and Linda Chamberlain, and were then cut into wax stencils for in-house printing, using an Addressograph machine. Pages were collated, stapled and bound with black electric tape; again, in-house, and by hand.

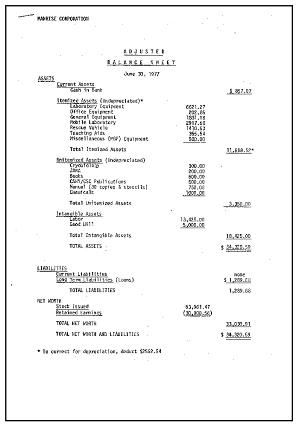

• Kept the books and prepared meticulous financial statements using an IBM Selectric typewriter:

I think it is most important to point out that all of this effort was undertaken prior to placing our services ‘on offer’ to the public and attracting media (and thus regulatory) attention. We made ourselves into professionals first. We taught ourselves hypothermic organ preservation, basic surgical skills, the fundamentals of extracorporeal perfusion, a great deal of pharmacology and medicine, a fair bit of practical cryogenic engineering, and lots of crafts skills; ranging from electrical wiring, simple circuit design, wood working and basic construction…. And we mastered the biomedical and surgical procedures required to conduct animal research.

I think it is most important to point out that all of this effort was undertaken prior to placing our services ‘on offer’ to the public and attracting media (and thus regulatory) attention. We made ourselves into professionals first. We taught ourselves hypothermic organ preservation, basic surgical skills, the fundamentals of extracorporeal perfusion, a great deal of pharmacology and medicine, a fair bit of practical cryogenic engineering, and lots of crafts skills; ranging from electrical wiring, simple circuit design, wood working and basic construction…. And we mastered the biomedical and surgical procedures required to conduct animal research.

It took us 4 years of concentrated effort to do these things, and tremendous outreach, correspondence and collaboration with every ‘expert’ we could find and who was willing to help us. Only after all of this was in place did we (fortunately) do the first case.

Without question this is how cryonics should have been launched in 1964. It was unarguably tragic that competent and utterly dedicated medical, engineering and scientific minds did not arrive on the scene until the late 1960s, and were not empowered to act until the early 1970s. Indeed, the primary reason that proper planning and implementation of cryonics were delayed, was the fact that when the Chamberlains, Greg Fahy, Art Quaife, John Day (another engineer) and I became involved, we were (for years) mislead into believing that cryonics was, in fact, being competently implemented. It was the realization by Fred, Linda, Greg, Art and I that CSC was a fraud, and that the Cryonics Society of New York was failing, that spurred the creation of Alcor and Trans Time.

So, this is my advice to you: Master cryonics first. Realize that no one else will do this but you. Reach out to and employ experts whenever you can. Gather and master the 45 years worth of knowledge so painfully acquired in launching cryonics in the US. Be prepared to suffer a great deal and to have things move much more slowly that you anticipate. Ask questions, communicate, and generate a comprehensive technical and business plan which calls out and prices of all the elements of the program, in terms of both materiel, and human resources.

Mike Darwin

Mike, this is offtopic, but what does the logo on your shoulder mean in the picture at the top? Anything?

I have the feeling it’s going to be one of those things everybody knows but me. :)

I doubt anyone will know. If they do (other than me) I guess we’ll find out ;-) — Mike Darwin

Is it the logo of that ‘Cryonics Defense League’ mentioned in the other post (Specimen Standards for Evidence-Based Human Cryopreservation Organizations, Part 1)?

A year late, but it is the Germanic Valknut

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Valknut

I can only guess as to its personal significance for you, but interestingly (and perhaps coincidentally), it may have inspired the Suebian knot hairstyle not uncommonly found on Europe’s famously well-preserved bog bodies (as noted in the wikipedia article).

More on the symbol (aka “Borromean triangles”)-

http://www.liv.ac.uk/~spmr02/rings/vikings.html

Fascinating stuff, Mike.

I’d like to think that Valhalla is Earth circa 2xxx. Hopefully, I’ll see you there.

interesting post. Nice pic of ettinger. WW2 vet, huh? The Greatest Generation and all that. Physics prof. I can relate. I am a vet myself and my first real job was in the field of nuclear physics. I agree that the lessons learned and the history are invaluable for future cryonics orgs. But then again, this cryopreservation tech stuff is all small beer compared to the issues of culture and societal taboos and ideological infrastructure.

“Cryopreservation tech stuff?” This is a pretty diverse site in terms of formal posts, considering that so far just one man is writing it all. And I would add that you haven’t been restricted here. If you have some fine writing on “issues of culture and societal taboos and ideological infrastructure,” I’d be fascinated to seen it. Complaining about others not following your DIRECTIVES such as (and I summarize accurately, in no particular order):

1) Sell cryonics via religion and get church going religious people signed up, and visible as members.

2) Loose the “nerds” like Ralph Merkle, who, I might add, as a very on-point aside, has contributed more value to the world economy than I would guess at least 95% of the population, and while I think Ralph has done considerable harm to cryonics, it would be both ungrateful and stupid for me not acknowledge his concise statement of the information-theoretic criterion of death. He is widely and well respected in the fields of cryptography (which underlies technology from your automatic car door opener to the brass tacks of security for computers and the banking system) as well to quantum computing theory. What have you done lately, except to anonymously post here?

3) Denigrate every idea that anyone has anywhere about cryonics, except yours (which so far I count 2).

Commands or demands that people follow a given course of action, even a good and wise course of action, basically count for shit – to be blunt. The only time they are of any use is when someone is about to step backwards off a cliff and you have 2 seconds to warn them. And the pity is, that even then, mostly what you’ll get is either a puzzled or a cross look, as they step off the edge. If you want action out of people you must tell them how, where, and WHY. The world is full of people, from the clever to the moronic, shouting at all of us: “Do This!Don’t do that! Buy this! Go here! Believe this! Don’t believe that.” We’re all sick of it. At least when we watch commercial TV, or listen to the radio, the hucksters are paying for the programming, and not infrequently what they are selling is at least worth knowing about, or the way they are selling it is amusing, and/or clever.

By contrast, you are merely boring. Not irritating (yet), not provocative, just boring. And also snide, and not infrequently rude. Come up with something more substantive than kooky injunctions (absent any argument, crazy or rational) or take your typing elsewhere. — Mike Darwin

>I think Ralph has done considerable harm to cryonics

Would you care to explain in what way?

Eric Drexler was (is?) a realist, and a bit of a pessimist, IMO. I remember when I first met him that he seemed “gloomy,” and I’ve got to say, I really liked that about him. Because when a guy shows up at the door of your lean-to on the African savanna with the idea of fire, you don’t want him to be jumping around shouting “Tee hee! Tee hee! Fire! I’ve found fire! Don’t you realize that means filet mingon, shrimp on the barbie, and central heating??!! Tee hee!

NOT.

Drexler was thoughtful; I could tell he loved the idea he had conceived, and I could equally tell he was well aware of its power for good. But to his credit, that wasn’t what he was about. You know, I still have my copy of The Future by Design, which was the rough manuscript he sent to Alcor for comments. It is a very different book than what it became: Engines of Creation. And one of the really remarkable things about Drexler was that he listened. He didn’t just send the book around for comments to see what the “soft spots” might be. He really listened to what his critics had to say, and he made very substantial changes. And he gave credit where credit was due. I admire him tremendously, and I must say that I’m very glad to hear that he is out from under the shade of The Foresight Institute Tree.

Merkle is a very pleasant man; seemingly childishly enthusiastic and easy going. Also seemingly very realistic. Maybe he is in some context other than cryonics, and in fairness to him, I’d have little in the way of remarks to make vis a vis his negative impact on cryonics, if he hadn’t been put on the Alcor Board. But where cryonics and Nanotechnology (upper case N intended) intersect, Merkle has behaved in ways that have, cumulatively, been very damaging to cryonics. Once you believe in the Big N, then everything else that’s difficult, or problematic, or messy, or hurtful to deal with, can be safely put on the back burner, because if someone isn’t doing a good job (or even a competent job) with Transport or CPA perfusion, well, Big N will take care of that. Think about this, Merkle is a scientist, who ought to ostensibly have great respect for research, and yet Alcor has done virtually no meaningful research in 20 years. And they have given grants to fund revival research using, you guessed it, Nanotechnology. But when you think about how Merkle is a scientist it all starts to make sense. He’s a cryptographer and a guy who makes models of nanobearings. That’s great, and it can be vastly practical and useful. But what it isn’t is bench science. You can go back and run your simulations and code cracking evaluations forever, literally forever (if Merkle is right), but you don’t get that “many times theory” of cryonics with the real Mike Darwin or the real Mark Plus. Engineers and theoreticians must be linked, joined at the hip when it comes time to interact with the everyday world of “one and only people” who’s lives can’t be rebooted; and the simulation run over and over again – at least not by us, and certainly not yet.

Nanotechnology isn’t real. In fact, it is much, much less real than cryonics, because there are, in fact, real cryopreserved people, and they can yield all kinds of data now, and they can/will have individual and very real outcomes, ranging from thawed and lost, to revived and well. Nanotechnology is science-fantasy. Yes, nanotechnology is real, and there are rapidly growing applications for it with each passing day. But it is mostly unglamorous stuff. There are no nanoscale cell repair robots with mechanical (atomic scale) bearings and itsy bitsy rod logic computers. And if I were a betting man, I’d say there won’t be. To put one cent on research into that kind of repair scenario, or any kind of repair scenario that has no imminent physical implementation, is foolish. Maybe a handful of people are happy to get cryopreserved with their neurons squashed like bugs by ice, but count me out. I want to put as little burden on the future as possible, because I don’t believe, as Ralph does (and he’s said so) that “comes da Reevolution” the future is going to arrive all grown up, and ring our doorbell, and summon the attendant at Alcor or CI, and say, “OK guys! Everybody outside and play! It’s recess time! The Big N Man is here to save the day!”

The future comes in fits and starts, often with long black periods of darkness, and always, always with setbacks. Want an example “ripped from the headlines?” Japan, right now. What a hell of a mess. I may even make up a cartoon of the Great Council of the Cave Men sitting in session, delivering their summary judgment on their Prometheus. “We’re very sorry Ugga Bugga, but our projections show that in one of the most technologically advanced places in the world fully 10,000 years from now, a place called the US of A, six thousand people will be burned to death each year! Since we don’t have decimals yet, nor multiplication, we can’t tell you how many people will die due to cave fires between now and then, but we figure its more than have ever lived in Roccabacca Land. Forget it. No fire. Too dangerous. And what a horrible way to die!” Play with god’s things, be prepared to sustain god’s losses. There is no “get out of jail free card” in this “game.” Merkle never got that, and probably never will

Finally, the whole idea of Nanotechnology as anything other than an idea, a realistic “possible” pathway to achieve recovery of cryonics patients is toxic. It becomes a substitute for god in the ancient catchphrase, “With god, all things are possible.” Well, maybe, but WHEN? Tank time is risk time. Ralph never got that either, and I don’t think he ever will. Right now (and not surprisingly to me) the Japanese simply went off and left their old and sick near Reactor City. They didn’t move them, they didn’t send in food and medicine. They just left. And no, I’m not making that up; it is, in fact, very Japanese. How do you think the cryopreserved will fare when the first really big cluster fuck with teentsy tiny machines happens? And you had better believe that it will happen – because it will be your only defense against it, and your last best hope of surviving it. — Mike Darwin

Wow. I got flamed on Cryonet for expressing skepticism about the “Big N,” as you call it, especially by Perry Metzger (another of the socially retarded individuals drawn to cryonics). That kind of irrational hostility supports the “cryonics cult” stereotype. Glad to find someone else who hasn’t drunk the Kool-Aid.

I’ve also had problems with using Alcor’s money to support Merkle’s and Freitas’s “nanomedicine” hobby. For the past generation many cryonicists have invoked the Big N as a way to shrug off fucked up suspensions. I rather wish now that Drexler had ignored cryonics in the 1980′s, instead of going out of his way to associate his ideas with it.

BTW, do you have any reason to believe that the stagnation in the cryonics movement has something to do with the increasing skepticism about Drexler’s Nanotechnology? Has anyone dropped out because he said he doesn’t find the Big N revival scenario credible, for example? I have no emotional investment in Drexler’s reputation, or in Merkle’s or Freitas’s, for that matter. If their Big N idea sucks, we need to acknowledge that fact, eat the sunk costs and move on to better ideas.

Oh yes, one more thing. If this is such a useless and crappy site, and everything here is “small beer,” and to boot, I’m a “blue haired or blue nosed reactionary,” why do you keep reading the articles here, and even more to the point, WHY DO YOU KEEP POSTING HERE? Why aren’t you off running in the tall grass, where the big dogs pee? — Mike Darwin

mike, you are doing your best to get offended. Just relax and unwind a little bit there.

I’ve met Ralph Merkle. He’s a computer guy. Probably one of the best in the world. He’s also a likable guy. The problem is that cryonics, and any possible method of revival is based on biology, which in turn is based on chemistry. Ralph does not know either chemistry or biology and has not worked in a biotech lab. Thus, his speculations are based heavily on computer science, which is the field he is an eminent leader in.

This is the reason why Thomas Donaldson is one of the few people worth listening to on the issue of potential revival technologies. His background is in chemistry and biology. The problem with the big “N” as our host puts it, is that it is conceived by those whose background is in computer science and, maybe if you are lucky, semiconductors and materials science. I do not have background in either chemistry or biotechnology. But I do know enough of these fields to understand where the computer modeling approach is very limited. My experience is that computer science people seldom understand materials science (a field I do have background in), let alone chemistry and biology.

Cryonics should not be working on the revival process right now. The work should be in improving the front-end process (e.g. better cryo-preservation). Above all, it should be in the elimination or at least minimizing of ischemic injury prior to cryo-preservation. Next would be low-cost, robust storage above the temperature at which fracturing occurs. The cryonics organizations ought to be licensing the technology developed by 21cm, CCR, and others. I do not know why they do not do this. It appears that many of the technical issues involved in effective cryo-preservation have been or are close to being solved by these companies. The cryonics organizations need to work more closely with them.

Some current status on the feasibility of “dry” nanotechnology (aka molecular manufacturing):

http://nextbigfuture.com/2011/03/philip-moriarty-discusses.html

This is an interview of a guy who got money from the U.K. government to research the possibility of molecular manufacturing. In short, he thinks “dry” nanotech is not possible for the manufacture of macro-scale objects. “Wet” nanotech, on the other hand, seems to be developing by leaps and bounds.

I think that cryonics must abandon the notion that “dry” nanotech is going to be there to reanimate us. This is why effective brain cryo-preservation is so necessary. The rest of the body can be regenerated using some kind of stem-cell based regeneration therapy or some kind of synthetic biology (maybe the stem cells are synthetic biology). But the brain has to be repaired on an intra-neuronal level, which is more technically demanding than simple cell-based regeneration. We need a scenario where this can be done using biologically-based technology, the less of it needed, the better it is. If the brain really is cryo-preserved at the neuronal and dendrite level, then we might not need this capability at all.

Comprehensive whole body regeneration (e.g. stem cell based) is likely during the second half of this century (like 2080 or something). Repairing of the brain on an intra-neuronal level is going to add another 50 years at least to the time we can be reanimated (mid 22nd century). As a wise man once said “capsule time is bad time” (of course this man is doing capsule time now, but thats a whole other story). One of the purposes of cryonics is to reduce the capsule time.

The other point is that the whole body regeneration is likely to be developed by the bio-medical industry for repair of trauma injury and disease. Development of the intra-neuronal brain repair technology will have to be done by cryonics people themselves (our future compatriots!). The reason is that this capability will not be so popular outside of cryonics and, hence, will not be developed by outside third parties. On the other hand, some brain repair will be developed by outside third parties to cure people of strokes, Alzheimer’s and other neuro-degenerative conditions. So, some of this work might get done for us by outside parties.

Of course, we will have to develop the fully integrated reanimation process that combines all of these repair capabilities on our own. No third party is going to do this for us.

We should pay attention to organ printing as a non hand-waving way to build new organs and even entire bodies:

http://www.box.net/shared/p3idvxvlcb

There are three technologies that we are likely to get in the next century or so:

1) Bio-engineering or “wet” nanotechnology

2) space development – O’neill scenario on steroids

3) fusion power – IEC polywell, Tri-alpha, maybe Ni-H solid state LENR (Yes! I’m becoming convinced this is real.)

We’re not going to get “dry” nanotech, the AI/uploading, or the “singularity” at all. We won’t get any of the other fantasy stuff either.

In other words, we’re going to be “biological” for a long time to come. You might as well get used to it. We’re also going to have to work, start businesses, and make money as well, in order to survive. You might as well get used to this as well.

The wild card is (and these are real wild cards, so don’t give me any flak for mentioning them) technology based on Woodward-Mach effects and Heim Quantum Theory. I will know more on the first one come this summer and the second requires superconductor materials that will take another 5 years to develop such that they are cheap enough to do the experiment without breaking the bank.

It’s a bad idea to be over-specific when predicting the future, as that most frequently leads to wishful or fearful thinking. I’d say there’s a huge probability of advanced wet nanotech, and there is a somewhat less huge probability of dry nanotech. They aren’t mutually exclusive possibilities, and dry nanotech is still an exciting prospect. A prediction of biological immortality is higher in probability than both of them as it is enabled by the comparatively better known forms of genetic engineering. Curing all diseases less severe than aging (all infectious diseases, cancer, etc.) is more probable still, and so forth.

The sheet “Lack of Professionalization” (L10.jpg) is duplicate.

Hm. You can find the sheet above and below the text “lack of professionalism”.

Just another comment, obvious and oft-stated on this blog but (very much) worth repeating IMHO-

Referring to patients as “dead” is indeed one of the great fundamental missteps of nascent cryonics, and it remains a powerful barrier to public understanding let alone acceptance.

Patients are “dead” = Ahhh, so you’re storing frozen corpses. Grotesque. Macabre. Repulsive. Kooky.

Patients will be “brought back to life” = Reawakening corpses. Ridiculous. Frankenstein. Zombies. Unworthy of further consideration.

People (correctly) understand and appreciate that you can’t breath life into a graveyard, that “bodies” are not entities. The future of cryonics, then, might depend on challenging public misconceptions about that very narrow (arbitrary) line between life and death on the hospital bed. I understand that this is a touchy area where the legality of cryopreservation is concerned (ie; cryonics can’t be involved until “legal” death pronounced by third party)…nevertheless, I think it’s incumbent on these organizations to be honest about the underlying rationale behind the practice.

The best case scenario for an individual cryopreserved *today* using technology available *right now* is that he/she is NOT in fact dead! …that the invididual actually *DIDN’T* die on the hospital bed in the first place! Maybe not so good for the courts…but once people appreciate this, they’ll do an instinctive double-take on cryonics.

I think Cryonics would be best served by essentially abandoning speculation about future technology (which is typically what most media people love to talk about- prognostication)… Instead, we should be as IN-YOUR-FACE as possible about what death *is* and *isn’t*.

Don’t use words like “recoverable”….focus on the moment of death. Tell people “Guess what? Your terminally ill mom and dad DIDN’T REALLY DIE when they were pronounced dead in the hospital and the medical staff stopped trying to save them and pulled the covers over their faces.” What REALLY happened was that they entered into a condition of health from which CURRENT TECHNOLOGY is too inept to save them.

Use real-world relatable analogies; soldiers wounded in Iraq who are ALIVE and functional RIGHT NOW whose injuries would have been a death sentence in Vietnam. People who suffer catastrophic brain injuries in car accidents but are kept alive in coma from which they might be able to awaken and go on to return to society.

Go pluck out the highly-trained, highly-skilled ER doctors of 1955 and present them with Gabby Giffords just moments after taking a bullet to the head. If it had been up to them, their course of action limited by the tools they had, Giffords would be in the ground right now.

Point out that this is *real*- limited access to medical technology in some parts of the world means that someone critically injured or ill in sub-Saharan Africa might *actually* be declared dead when the same person could be kept alive in a major city in the US. That’s not a fantasy.

The most highly-skilled doctors and nurses with the best intentions are limited by our pathetic technology *the SAME way* doctors in some poor country might be- Just as better technology *actually* exists but is out of reach of some sub-Saharan doctor, better technology exists out of reach of the best US doctors too; it exists in the future.

Ask if they doubt whether or not some terminally ill or wounded patient who dies today might be saved and kept alive by future technology. That’s the *ONLY* bit of imagination that anyone learning about cryonics must concede.

Once prospective cryonicts understand that the current criteria for legal death amounts to make-believe, that it’s an artificial line drawn by *people* (not God, if you like) and defined by the limits of our technology…then we can offer a solution.

Now that first part may be incendiary, it may be hurt some people, it may be controversial…but I’m convinced that it’s something people can wrap their head around….something that may light a fire under them. Your loved ones *weren’t* dead; they *didn’t* have to be buried or burned; God (whether the God of Spinoza or Abraham) DID NOT decide to “take them,” our current technology FAILED them. Plain, frail, mortal, ignorant *people* FAILED them.

As controversial as that might be if it (or something along those lines) was the unflagging public banner of cryonics in all communications with the media, it’s something that has the potential to establish a raw, fundamental connection with people. A tangible line they can grab hold of and follow, if they wish.

“Bringing frozen dead corpses back to life” isn’t going to cut it.

Once the lay public appreciates that the line between life and death is make-believe, fake, that it depends on technology and not the forces of God/nature…then they are primed to see cryonics as the next logical step; we can’t yet revive people who’ve crossed that threshold, but we can do the next best thing;

stabilize them over the long-term until our technology *GETS BETTER* enough to do something about it all.

I would avoid words like “revive” as well as “recover”; instead, use the word “SAVE”. Instead of musings on exactly what kind of technology will be around in the future, we need only say that we’re waiting for technology to “GET BETTER”…which anyone can agree that it inevitably will.

(hence the following, keywords in bold)

So in other words, cryonics is a way to SAVE DYING (not dead) PATIENTS who are being FAILED by CURRENT TECHNOLOGY and who can be SUCCESSFULLY TREATED by BETTER TECHNOLOGY that WILL EXIST sooner or later.

These PATIENTS are not in storage (avoid that word), they have been STABILIZED for the long-term, however long it takes for BETTER TECHNOLOGY to TREAT THEM.

Cryonics, then, is not unlike what paramedics do; cryonics is *merely* the best form of long-term biomedical stabilization humanity has right now. If cryonics is unworthy of consideration, then you shouldn’t care whether or not paramedics perform CPR on you or your loved ones.

(sorry if it got ranty…just some free flow ideas on how I think cryonics could be better communicated to the public)