10 February, 1974 “Air Hearse”

10 February, 1974 “Air Hearse”

I was 19 years old and I had never flown in a light aircraft before. I had had very little sleep for the three days prior to the start of the flight. “Gasoline rationing” was in effect in the United States and most of the West, and there was an atmosphere of impending socioeconomic doom. We arrived at the airport in Cumberland, Maryland on an overcast and freezing day. The skies were spitting snow flurries and our fingers were numb and stiff with the cold. The hearse pulled up next to a gleaming Cessna Piper Cherokee and a stunning looking woman dressed in tight jeans and a leather jacket and boots emerged from the cockpit. Her long brown hair was lofted and buffeted by the freezing wind, and her eyes were two mirrored orbs of reflective plastic. I don’t notice women much, but even these many years later I can see her in mind’s eye and realize that she was an extraordinary human being, and a beautiful woman. Her name has vanished from my memory, but the name of her plane, at least the non-numerical portion of it , is not forgotten, it was Whiskey.

She ran a company called Air Hearse and her business was the quick transport of the dead to anyplace her Cherokee could reach. We stood on the freezing tarmac discussing possible destinations. Could she take us directly to Emeryville, in Northern California? She lifted the sunglasses exposing her eyes to the tiny shards of wind driven ice. Matter of factly she said, “That would be difficult and a bit dangerous. I’d have to gain a lot of altitude to get over the Rockies. We’d definitely need supplemental oxygen. It’s gonna cost you plenty.”

The mortician, shifting his weight from leg to leg and shivering in the cold, suggested that we get our cargo out of his terrestrial hearse and into her celestial one, so he could be on his way. We could sort out where were going on our own time.

The Cherokee had a large slide-aside access door to the cargo area which was opened, and the hearse was backed up, end to side, to the aircraft. I don’t recall how many of us there were, but it was not enough. The patient was in an inexpensive cloth covered fiberboard coffin. He was not a petite man and he was covered in approximately 300 pounds of dry ice. A weight of 500 or 600 pounds was probably reasonable for the frigid bier and the still incompletely frozen man inside of it. The pilot was used to the mechanics of loading bodies into the tiny hold of the Cherokee, but this was another matter altogether. Without rolling dowels, the coffin became enormously difficult to turn and slide inside the confined space of the cargo hold. The pilot began to shout that we take care not to damage her aircraft. I became concerned that the now frigid, flimsy, glued together coffin would disintegrate under the load and the torque of being heaved into the airplane. Frozen fingers and jostling bodies made the task almost impossible to accomplish. But we did it.

The runway at the Cumberland airport extends to the edge of a cliff and then gives way to sky and space, or to earth and death. We were heavily overloaded. As we left the end of the runway the Cherokee sank sickeningly, and then recovered. The snow dusted crags and crevices of the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians unfolded before us. The view was fogged slightly white with lightly falling snow. As I looked around and tried to recover my equilibrium from the terror of takeoff, I noticed that I was not succeeding. Over the ensuing minutes I became increasingly breathless and the mother of all headaches began to descend. I was sufficiently self absorbed in trying to stem my “rising panic” that a few perilous minutes more passed by before I looked over at the pilot. She was breathing rapidly; almost on the edge of panting.

I looked back over my shoulder at the gray fabric draped coffin. It was virtually un-insulated – perhaps an 1/8th of an inch of fiberboard with another ½” or so of shredded wood excelsior. More to the point, the patient inside was still mostly well above 0○C and covered in dry ice. The volume of sublimated gaseous carbon dioxide being generated must have been some fearsome number of liters per minute. I turned to the pilot and asked if she was short of breath. The answer was a thoughtful shake of her head in the affirmative. Once I explained the situation we were in I learned something interesting about light aircraft, or at least about Piper Cherokees: you can’t simply roll down the window to let fresh air in.

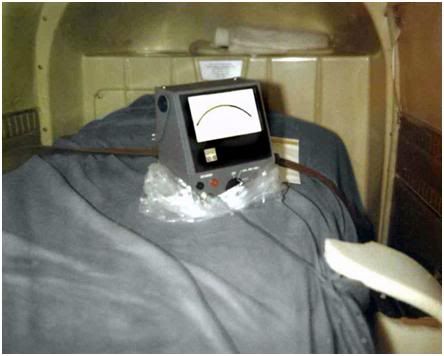

By this point, we were both panting and our visual fields were becoming impaired. Things begin to get dark around the periphery and it becomes a task to focus on the still clear center of your visual field. Fortunately, “Whiskey” had two small, flap-like cutouts in the glass of both the pilot’s and passenger’s side windows. We could breathe as long as we kept our noses and mouths in close approximation to the small apertures admitting wisps of fresh air into the cabin. Finally, my heart rate settled down to a brisk staccato and I twisted around in the seat, the shoulder belt biting into my neck, and took a picture. The Polaroid SX-70 spit out a milky gray rectangle that slowly matured into a spotted and slightly out of focus image.

If you want to see into the mind of a man give him a camera and see what he photographs. That is as close as you will come to seeing the world through his eyes. There are no photos of the beautiful and remarkable pilot, or of the harsh and craggy Appalachians. There is only this solitary photo of a man cooling to dry ice temperature in a desperate bid for immortality. For me, that was enough, then and now.

As we headed towards Detroit, our destination, the sublimation rate declined and the ingress of fresh air began to better sweep out the evolving carbon dioxide. Still, it was barely enough. It was then that I got my first lesson in the physics of the partial pressures of gases. The pilot informed me that the decreased pO2 due to our altitude was probably making the hypercarbia from the sublimating dry ice worse. We would have to descend. This information was communicated to an air traffic controller who, after a quick consult with his colleagues, averred: We could not descend; the flight path was not clear. “Well boys,” our pilot said with icy calm, “I suggest you clear a fucking flight path for us, because I have no intention of suffocating up here.”

I did not see Detroit from the air that day. Forced as we were to fly at a reduced altitude we entered into the heart of one of the worst snow storms the Detroit metro area had experience in many years. The pilot ignored the many orders to divert Whiskey to another airport and we landed in snow that was halfway up my calves. Unloading the heavy coffin was a nightmare in the snow, and I feared that the elderly Mr. Mott, the Cryonics Society of Michigan’s mortician, would be felled from a heart attack amidst the swirling snow cloud that enveloped us.

The trip from the airport to the mortuary proceeded at a crawl through the fast accumulating snow. Thick sheets of snow alternately coated and peeled off from the slowly turning tires of the few cars ahead of us that were still out on the road. It was warm and dark inside the front of the hearse and Mr. Mott had the radio on. “Well son, just your luck to get here in the middle of a blizzard,” he said. “Yes, just my luck,” I replied, as I looked out into darkness of a city now fully engulfed in both snow and night.

– Mike Darwin

cool story, bro….