Figure 1: Corporations were created by people to be potentially immortal, and yet, on average, they have life spans much shorter than people. Very interestingly, they have about the same maximum life span as people: ~120 years.

By Mike Darwin

On the Importance of the Longevity of Corporations to Cryonics

So what did 6 years and $1.25 million of last years’ money buy for Alcor and cryonics between 1983 and 1989? In the next part of this article, I’ll endeavor to answer to that question. I’ve listed most of the milestones Alcor logged during that interval as documented in Cryonics magazine, but I’m sure I’ve missed some. Since I lived those years and they were, for me personally extraordinarily happy and productive ones, I’m simply too close to them to have any pretense to objectivity. However, I think it likely that others will readily supply anything lacking in that regard. If any of you reading this have suggestions for what should appear on that list, please email them to me at m2darwin@aol.com.

Figure 2: Some of the principals who contributed to Trans Time’s dynamicity in the 1970s and 1980s. From foreground to background and left to right: Jim Yount, Jerry White, Art Quaife, Judy & Paul Segall, Dick Marsh, John Day, Norm Lewis, Carmen Brewer and Ron Viner. It is soberi9ng to note that Jerry White, Dick Marsh and Paul Segall are now in cryopreservation and Carmen Brewer is decased.

It is also important to understand that Alcor was and is but one organization and one epoch in the history of cryonics. During the 1970s and into the early 1980s Trans Time, Inc., (TT) under the leadership of Art Quaife, Jim Yount and John Day (operating in the San Francisco Bay Area) reshaped the way cryonics was both perceived and marketed. They also made a number of significant technical advances in engineering and in the mathematics of heat flow and cryoprotectant equilibration. They brought dynamicity and renewed hope and energy to cryonics and were in no small measure responsible for recruiting a number of people who were subsequently essential to Alcor’s success throughout the 1980s, and beyond. I would be remiss if I did not note their enormous contribution. What’s more, I believe it is likely of considerable importance that a thorough analysis of the history of TT be undertaken. TT produced shareholders’ reports with detailed financials, and they produced voluminous minutes of their monthly meetings.

However, that is not data I have access to and it is not a task I’m well suited to perform. I would, however, note that given the nanoscopic experience base in cryonics compared to the rest of the institutional world, we need to carefully dissect every failure and every success. Why? Because our undertaking is fundamentally different than any that have come before it. Biological evolution proceeds with stunning results in just about the cruelest and least efficient way imaginable.[1] At no point does the process itself, or the organisms that comprise its unfolding need to stop and consider their predicament, or decide what to do next. As the gutter philosophers say, “Shit happens.” The price of such a blind, unreasoning process is the death and destruction of countless organisms, species, communities and cultures. Tennyson summed it up perfectly in “The Charge of the Light Brigade:” “Ours not to reason why, ours but to do and die.”

The modern corporation traces its roots to the 17th century, and the emergence of “chartered companies,” such as the Dutch East India Company. It is thus a species that is only ~ 500 years old. Until the 19th century, almost no attention was paid to why and how businesses came into and went out of existence. It was just something that happened, and it was taken for granted, like old age and death in the biological world. And it was not until the opening of the 20th century that scientific methods were brought to bear to study the fates of business enterprises – for profit or otherwise – and even now, such studies are comparatively few and lack rigor.

This should come as no surprise because there really isn’t much reason for anyone to care. Enterprises are like rabbits on a farm; as long as the population as a whole is healthy, there will be plenty of them and the fate of the individuals is of no consequence. It is only when epidemic disease, or another systemic calamity devastates the hutches, that there is concern over mortality. The same is true of epidemiologists; they are concerned with the fate of individual humans only as it impacts population-wide mortality and morbidity. A consequence of this is that we know shockingly little about how to extend the lifespan of corporations. Put another (and far more ominous way), cryonicists are faced with the task of finding not just a way to indefinitely extend the human lifespan, they must also find a way to indefinitely extend the lifespan of the corporate entities they propose will care for them and recover them from cryopreservation over a period of many decades, or centuries.

Corporation Gerontology?

The seminal cryonics thinker Thomas Donaldson was preoccupied with examples of institutions which lasted for centuries. He liked to cite the examples of the King’s Colleges in England, and of Westminster Abbey. I remember thinking at the time, “Well, that’s interesting and exciting, but it is also, I think, pretty uncommon. More to the point, how do we make that happen for our organizations?” Thomas and I exchanged letters about this, but I was never able to communicate to him that just because it has happened doesn’t mean it is likely, and it doesn’t mean it will happen for us. Thirty plus years ago, when we had those discussions, no one had yet generated any statistical data on the longevity of corporations over time.

We now know that the odds of a corporation surviving for 100 years is probably in the range of 1.0 to 1.5% , and of one surviving for 500 years, much, much lower; even if institutions like Oxford and Westminster Abbey are included in the data set. In fact, the average life expectancy for even multinational corporations of Fortune 500 caliber, or its equivalent, is only 40 to 50 years. And what about corporations as a whole, a 2002 study by Ellen de Rooij of the Stratix Group in Amsterdam indicates that the average life expectancy of all firms, regardless of size, measured in Japan and much of Europe, is only 12.5 years. Incredibly, no data exist for US corporations that I’ve been able to find.

Figure 3: The author standing next to the “John Snow Pump” on Broadwick Street, Soho, London in May of 2011. Snow is justly considered the father of epidemilogy for his work in pinpointingthe source of cholera outbreak in London in 1849 as the public water pump on Broad Street (now Broadwick Street). The municipal authorities removed the handle from the pump to prevent the local residents from usingthe water. The handle remains off of the pump except for one day of the year, John Snow Day, when it is cerimoniously put back in place.

Figure 3: The author standing next to the “John Snow Pump” on Broadwick Street, Soho, London in May of 2011. Snow is justly considered the father of epidemilogy for his work in pinpointingthe source of cholera outbreak in London in 1849 as the public water pump on Broad Street (now Broadwick Street). The municipal authorities removed the handle from the pump to prevent the local residents from usingthe water. The handle remains off of the pump except for one day of the year, John Snow Day, when it is cerimoniously put back in place.

Figure 4: The Living Company: Habits for Survival in a Turbulent Business Environment by Arie De Geus is one of the first books to examine why corporations have the life spans that they do. As such, it is a seminal work much deserving of cryonicists’ attention.

The study of corporate hygiene and pathology seems to be where medicine was in the 17th century. There is a great deal of cupping, blistering, bleeding and amputation – mostly to no good effect – and mostly carried out by incompetents (e.g., politicians, governments and nation-states). The concept of the “public health of corporations” is still nascent and the equivalent of the “John Snow moment” [2] of discovering how to halt the spread of business-killing epidemics, such as the one we are suffering right now, seems still in the future. The idea of a discipline in corporate medicine whose job it is to study the corporate aging process and extend corporate life span, has apparently just occurred to economists and business analysts.[1, 2] Like so much else in cryonics, no one else has the slightest clue or the slightest incentive to systematically study this problem and come up with solutions. It is simply a brutal fact of our time and place in history that the need to understand the processes attending corporate morbidity and mortality has simply not (yet) become an issue for human civilization.[3]

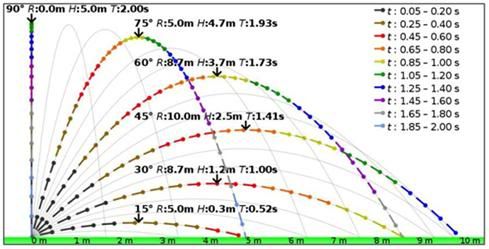

Figure 5: Trajectories of projectiles launched at different elevation angles but the same speed of 10 m/s in a vacuum and uniform downward gravity field of 10 m/s2. Points are at 0.05 s intervals and length of their tails is linearly proportional to their speed. t = time from launch, T = time of flight, R = range and H = highest point of trajectory (indicated with arrows). Corporations have similar arcs from launch to crash back to earth.

Figure 5: Trajectories of projectiles launched at different elevation angles but the same speed of 10 m/s in a vacuum and uniform downward gravity field of 10 m/s2. Points are at 0.05 s intervals and length of their tails is linearly proportional to their speed. t = time from launch, T = time of flight, R = range and H = highest point of trajectory (indicated with arrows). Corporations have similar arcs from launch to crash back to earth.

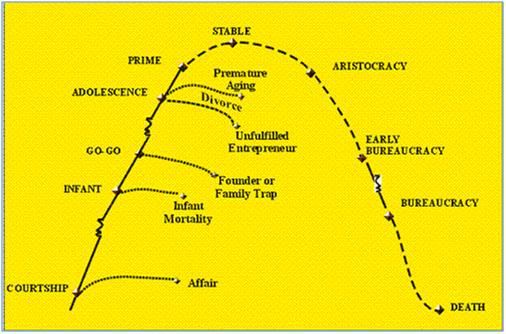

Clearly, some corporations remain fantastically innovative and productive over time while most do not; and there is evidence that they survive the longest. Two notable examples of the former are 3M (Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing) and Apple Computer. For a contrast with 3M, pick just about any has-been industrial giant of the past century. For a contrast with Apple there is Microsoft. While Microsoft is unarguably richer and larger, and no doubt most of those laboring there feel very secure, it is neither an exciting place to work, nor a particularly creative one. A careful analysis of these two examples of corporate robustness is beyond the scope of this series of articles, and most probably beyond the range of this author’s abilities. For now, it is sufficient to point out that these companies have interesting histories which may have value to cryonics. They also highlight the fact that most enterprises experience an arc, akin to that of a ballistic trajectory. In his seminal book The Living Company: Habits for Survival in a Turbulent Business Environment, Arie De Geus, the former head of Royal Dutch Shell’s Strategic Planning Group, maps out a life span arc for corporations (Figure 7)and notes that currently corporations “ exist at a primitive stage of evolution; they develop and exploit only a fraction of their potential.”

DeGeus may well be one of the first people to carefully consider why corporations have such appallingly short life spans when their very raison d entrée was their potential for immortality. I believe De Geus’s work is important for cryonicists to pay attention to, and I am going to quote him at length here on his observations regarding the characteristics of long lived corporations:

Figure 6: Arie De Geus

Figure 6: Arie De Geus

“After all of our detective work, we found four key factors in common:

1. Long-lived companies were sensitive to their environment. Whether they had built their fortunes on knowledge (such as DuPont’s technological innovations) or on natural resources (such as the Hudson Bay Company’s access to the furs of Canadian forests), they remained in harmony with the world around them. As wars, depressions, technologies, and political changes surged and ebbed around them, they always seemed to excel at keeping their feelers out, tuned to what-ever was going on around them. They did this, it seemed, de-spite the fact that in the past there were little data available, let alone the communications facilities to give them a global view of the business environment. They sometimes had to rely for information on packets carried over vast distances by portage and ship. Moreover, societal considerations were rarely given prominence in the deliberations of company boards. Yet they managed to react in timely fashion to the conditions of society around them.

Figure 7: The arc of the corporate life span as proposed by by Arie De Geus. Note that the terminal phase is bureaucracy where in the corporation becomes unresponsive to its environment and becomes increasingly insulated from both new opportunities and from its customers by bureaucratic mechanisms.

Figure 7: The arc of the corporate life span as proposed by by Arie De Geus. Note that the terminal phase is bureaucracy where in the corporation becomes unresponsive to its environment and becomes increasingly insulated from both new opportunities and from its customers by bureaucratic mechanisms.

2. Long-lived companies were cohesive, with a strong sense of identity. No matter how widely diversified they were, their employees (and even their suppliers, at times) felt they were all part of one entity. One company, Unilever, saw itself as a fleet of ships, each ship independent, yet the whole fleet stronger than the sum of its parts. This sense of belonging to an organization and being able to identify with its achievements can easily be dismissed as a “soft” or abstract feature of change. But case histories repeatedly showed that strong employee links were essential for survival amid change. This cohesion around the idea of “community” meant that managers were typically chosen for advancement from within; they succeeded through the generational flow of members and considered themselves stewards of the longstanding enterprise. Each management generation was only a link in a long chain. Except during conditions of crisis, the management’s top priority and concern was the health of the institution as a whole.

3. Long-lived companies were tolerant. At first, when we wrote our Shell report, we called this point “decentralization.” Long-lived companies, as we pointed out, generally avoided exercising any centralized control over attempts to diversify the company. Later, when I considered our research again, I realized that seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century managers would never have used the word decentralized; it was a twentieth-century invention. In what terms, then, would they have thought about their own company policies? As I studied the histories, I kept returning to the idea of “tolerance.” These companies were particularly tolerant of activities on the margin: outliers, experiments, and eccentricities within the boundaries of the cohesive firm, which kept stretching their understanding of possibilities.

4. Long-lived companies were conservative in financing. They were frugal and did not risk their capital gratuitously. They understood the meaning of money in an old-fashioned way; they knew the usefulness of having spare cash in the kitty. Having money in hand gave them flexibility and independence of action. They could pursue options that their competitors could not. They could grasp opportunities without first having to convince third-party financiers of their attractiveness.

It did not take us long to notice the factors that did not appear on the list. The ability to return investment to shareholders seemed to have nothing to do with longevity. The profitability of a company was a symptom of corporate health, but not a predictor or determinant of corporate health. Certainly, a manager in a long-lived company needed all the accounting figures that he or she could lay hands on. But those companies seemed to recognize that figures, even when accurate, de-scribe the past. They do not indicate the underlying conditions that will lead to deteriorating health in the future. The financial reports at General Motors, Philips Electronics, and IBM during the mid-1970s gave no clue of the trouble that lay in store for those companies within a decade. Once the problems cropped up on the balance sheet, it was too late to prevent the trouble.

Nor did longevity seem to have anything to do with a company’s material assets, its particular industry or product line, or its country of origin. Indeed, the 40- to 50-year life expectancy seems to be equally valid in countries as wide apart as the United States, Europe, and Japan, and in industries ranging from manufacturing to retailing to financial services to agriculture to energy.

At the time, we chose not to make the Shell study available to the general public, and it still remains unpublished today. The reasons had to do with the lack of scientific reliability for our conclusions. Our sample of 30 companies was too small. Our documentation was not always complete. And, as the management thinker Russell Ackoff once pointed out to me, our four key factors represented a statistical correlation; our results should therefore be treated with suspicion. Finally, as the authors of the study noted in their introduction, “Analysis, so far completed, raises considerable doubts about whether it is realistic to expect business history to give much guidance for business futures, given the extent of business environmental changes which have occurred during the present century.”

Nonetheless, our conclusions have recently received corroboration from a source with a great deal of academic respectability. Between 1988 and 1994, Stanford University professors James Collins and Jerry Porras asked 700 chief executives of U.S. companies-large and small, private and public, industrial and service-to name the firms they most admired. From the responses, they culled a list of 18 “visionary” companies. They didn’t set out to find long-lived companies, but, as it happened, most of the firms that the CEOs chose had existed for 60 years or longer. (The only exceptions were Sony and Wal-Mart.) Collins and Porras paired these companies up with key competitors (Ford with General Motors, Procter & Gamble with Colgate, Motorola with Zenith) and began to look at the differences. The visionary companies put a lower priority on maximizing shareholder wealth or profits. Just as we had discovered, Collins and Porras found that their most-admired companies combined sensitivity to their environment with a strong sense of identity: “Visionary companies display a powerful drive for progress that enables them to change and adapt without compromising their cherished core ideals.” [3]

Who are we Kidding?

Of course, as De Geus himself points out, these observations are just that – observations – they lack scientific rigor and they point up just how nascent an endeavor the study of corporate longevity is. There is also the fact that all of these studies are of for-profit corporations, and will likely continue to be, because that’s where the money is. Religious institutions and nation-states are already certain that they are immortal, so it seems unlikely there will be much study done in those areas of corporate health and longevity.

So, let us pause here and consider our predicament. For onto 50 years cryonicists have been trying to sell, promote, foster and even give away cryonics with very little success. What’s more, we are genuinely astonished when people look at us as if we are credulous fools. We can’t understand why they don’t “get it.” Can’t they see the dire fix they are in and thus appreciate that we’re the only in game in town?

Regrettably, that statement of the situation is a straw man; it is not necessarily a binary situation wherein if you opt for cryonics you may live again; and if you don’t you will certainly die. A good hard look at the data suggests that it is perfectly reasonable for people to believe that you can opt for cryonics and that it may be technically possible to achieve reanimation, but that you will still end up dead. Most people don’t need to run the numbers on a spreadsheet to understand this, because they are arguably more in touch with the reality of just how fragile the secular world is than are cryonicists. Indeed, the only institutions in common experience that endure for more than a century – or even just for a century, are religions, nation-states and fraternal organizations – and the odds aren’t very good (and the life spans aren’t very long) even for most of those institutions. England, as a continuously functioning nation-state, only goes back to the Restoration after Cromwell in 1660, a mere 351 years ago. The US has an even shorter lifespan of 235 years.

Figure 8: Offering someone a costly ticket on a plane that has a negligible probability of making the journey without falling out of sky is not much of an alternative to staying put, even in the face of certain death. At least you have the opportunity to enjoy the money you would have spent on a ticket to nowhere.

Figure 8: Offering someone a costly ticket on a plane that has a negligible probability of making the journey without falling out of sky is not much of an alternative to staying put, even in the face of certain death. At least you have the opportunity to enjoy the money you would have spent on a ticket to nowhere.

So, just who are we kidding? By way of analogy, it may be perfectly possible that a much better life in California awaits an unhappy man in the slums of Haiti today. However, he can understandably be excused if he fails to lunge at the opportunity to make the trip in an aircraft that has a 0.00000001 chance of successfully making the journey. The Cryonics Calculator is a useful tool for allowing us to objectify our assumptions about risk. But it isn’t the only such tool. The fact is that most people run that calculation at least once in their life (when they first hear of cryonics), and some run it a second time; when they find out they are dying. If cryonics doesn’t pass the credibility sniff test, then it simply does not exist as a reality for most people. They think we are as crazy as we think they are – we for buying into cryonics and them for buying into religion. But, and you have to give them this, leaving the workability of the product aside, they still have us beat when it comes to demonstrating even the barest possibility of institutional longevity much beyond a century – or three or four at most.

Think about that, and consider very carefully what we have done to demonstrate that the craft we propose to fly us across the decades, or if need be the centuries, possess any credible degree of airworthiness?

Footnotes

[1] Or so it seems to us, because we can reason and plan. Evolution is not a conscious process that can design prospectively. If that “defect” in its algorithm of progress is understood, then it is in fact remarkably efficient.

[2] Snow was a skeptic of the then dominant miasma theory that stated that diseases such as cholera or the Black Death were caused by pollution or a noxious form of “bad air”. The germ theory of disease did not come the scene until 1861 when it was proved by Pastuer. As a consequence, Snow was unaware of the mechanism by which cholera was transmitted, but evidence led him to believe that it was not due to breathing foul air. He first publicized his theory in an essay “On the Mode of Communication of Cholera” in 1849. By interviewing Soho residents with help drom Reverend Henry Whitehead, he identified the source of the outbreak as the public water pump on Broad Street (now Broadwick Street). Although Snow’s chemical and microscope examination of a sample of the Broad Street pump water was not able to conclusively prove its danger, his studies of the pattern of the disease were convincing enough to persuade the local council to disable the well pump by removing its handle.

[3] By contrast, a great deal of largely unscientific effort has been focused on the “biology” of nation-states and empires. Arnold Tonybee’s blighted 12 volume “A Study of History” is a classic case in point (A Study of History: Abridgement of Vols I-VI, with a preface by Toynbee (Oxford University Press 1946).

References

1. De Geus A: The Living Company: Habits for Survival in a Turbulent Business Environment Harvard Business Press; 2002.

2. Sheth J: The Self-Destructive Habits of Good Companies: …And How to Break Them Wharton School Publishing; 2007.

3. De Gues A: The Lifespan of a Company: http://www.businessweek.com/chapter/degeus.htm. Bloomberg Bussinessweek 2002.

I think one key to longevity for cryonics organizations is recognition by the leadership that this is a multi-century endevour. That reanimation, if possible, will not occur until the 22nd or even 23rd century. Will the U.S. exist as a currently recognizable political entity then? Perhaps the southwest will become a part of Republica del Norte by 2080. Or maybe the American republic will turn into the American Empire (just like Rome) and will absorb much of Europe and Latin America (differential birthrates, you see). How well these political entities and the people that comprise them be responsive to cryonics and radical life extension? Maybe we find ourselves in Shanghai, Singapore, or even a space colony out in the belt 100 years from now.

I think a lot of it is sound financial management. How do long-lived institutions such as the Vatican and Westminster Abbey invest their money? What about some of the long-lived banks in Switzerland and Isle of Man? Some of them have been around for 200 years. How do they invest their money?

As you may or may not know, all of the “developed” country’s governments have debt problems. How will this work itself out over the next 50 years or so? How do we preserve and grow our money through such a mess?

I’ve pointed out a similar problem with the idea of using Liechtenstein as a holding country for cryonics reanimation trusts. Look at how the borders in central and eastern Europe have shifted in the past 20 years. Nothing would stop a neighboring country or empire in a future century from absorbing Liechtenstein, voiding its laws about trusts and confiscating cryonicists’ assets.

Of course that assumes that Liechtenstein’s government would act in good faith in the first place. Apparently some cryonicist managed to piss off the government there and he had to get a court decision to force it to accept reanimation trusts. Yeah, smart move to introduce yourself to a county with a population about the size of Prescott’s, where everyone in the ruling elite knows each other, and many of them probably show up at the same family gatherings.

>How do long-lived institutions such as the Vatican and Westminster Abbey invest their money? What about some of the long-lived banks in Switzerland and Isle of Man? Some of them have been around for 200 years. How do they invest their money?

I imagine they derive financial stability from owning real estate free and clear.

I actually know the answer to those questions (insofar as outsider can) and they have little to do with real estate in either case. Westminster Abbey is one of my favorite places. No, it cannot even begin to compare to the Vatican (another of my favorite places). The Vatican is gloriously glamorous and the gentle climate of the Roma region has been kind to it. And the Vatican had Michelangelo, Raphael, Bernini… which Westminster Abbey did not. By comparison, the Abbey is a provincial cathedral in a backwater – impressive as it is. It has now become far too expensive for me to go to the Abbey, except for Evensong services. And when you go for those, you are carefully herded to the choir stalls and cannot wander the darkened church at night. They charge admission to the Abbey, and it is now in the range of $35.00 US. The last time I was there, as the guest of one the clergy posted there (my impression is that about as many of the upper echelon Anglican clergy are gay, as are flight attendants, worldwide) I asked what the yearly upkeep was. Since I’m terrible with numbers I don’t recall the exact amount, but it was in the many millions of pound sterling! And that’s per year!

So, let that be a lesson to folks with an “edifice complex” in cryonics: big structures take BIG MONEY to maintain and they suck it up continuously and at a truly gargantuan rate. I feel quite certain that whatever its advertising benefits, the Abbey is not making many converts to the Church of England. It is an amazing place, but it probably attracts more deists, agnostics, atheists, the merely curious and the intellectuals of other faiths than anything else, primarily because it is the resting place for many of the world’s greatest heretics. It’s really ironic when you think of it, that Newton and Darwin are buried there, and that there is now a stained glass window commemorating Britain’s greatest faggot: Oscar Wilde.

So, one reason they charge is because they have to, not because they can. Other monies come from a grab bag of sources: some from church owned real estate, some from the UK government (the Church of England is the state religion in the UK), some from charitable giving, some from foundations and trusts dedicated to the preservation of history and architecture, and so on. And of course, there is what in the accounting world is called “cash or cash equivalents.” Both of these institutions have huge cash reserves. You may remember the big scandal some years back about the Vatican bank, Banco Ambrosiano, or more properly, “The Institute for Works of Religion” (IOR) the bank’s principal share-holder. Archbishop Paul Marcinkus, head of the IOR from 1971 to 1989, was indicted in Italy in 1982 as an accessory in the $3.5 billion collapse of Banco Ambrosiano, which was accused of laundering drug money for the Sicilian Mafia which used Propaganda Due (“P2″), a mobbed-up Masonic lodge as an intermediary. P2 and its “Worshipful Master,” Licio Gelli, were also involved in providing cash to right wing terror groups during the 1970s. Archbishop Marcinkus miraculously escaped trial using the shield of diplomatic immunity. He fled to the US, where he lived in the in the Sun City retirement community in southern Arizona until his death in 2006.

This scandal is still ongoing as of last year http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/22/world/europe/22vatican.html . Roberto Calvi, “God’s Banker,” was found hanging (dead) under Blackfriar’s bridge in London. The positioning of the body was in keeping with Masonic ritual for dealing with traitors; P2 was also known as the “Blackfriar’s.” The Calvi hit was almost certainly for embezzling money from Banco Ambrosiano that was owed to him and the Mafia. It is quite credibly claimed that the Mafia wanted to stop Calvi from disclosing that Banco Ambrosiano had been used for money laundering with the full knowledge and consent of the Church. In the Italian trial that resulted, it was stated that Calvi’s killing was arranged in Poland, which may seem very strange until you realize that a large chunk of the money that funded the Solidarity trade union movement was provided on instructions from Pope John Paul II. This left the Vatican in an itchy position, since THEY were likely getting money from right wing groups all over the world, and probably from the CIA and countless business interests that wanted to see Eastern Europe opened up to the West.

So, never forget that institutions that survive for hundreds of years do so because they SAVE. They relentlessly accumulate capital, and they use it strategically to further their interests. THAT sometimes makes for strange bedfellows. The Vatican, the Mafia, Solidarity, the CIA, Spanish bankers, Western nation-states, corporate scions… —Mike Darwin

Mike, what do you make of the movie in the works about Bob Nelson?

http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/paul-rudd-boards-errol-morris-210432