By Mike Darwin

This series of lectures had its origin in a presentation entitled Cryonics: Why it has failed, and possible ways to fix it, which was delivered at an ExtroBritannia meeting on Saturday August 2, 2008 at Birkberk College in London, UK.

PREFACE

SLIDE 1

Before I begin the formal, structured part of this presentation, a few words are in order to put it into context. We live in an age where passion and strong emotion have been largely removed from daily discourse and are now considered acceptable only in the realm of fiction; in movies and video games. Characters there are free to speak in extremes and to speak passionately; not so those of us who inhabit the real world. I will be breaking that taboo today because what I am going to talk about is a life or death issue for you, for me, and for the 7 billion or so other human beings on this planet. My life matters to me a great deal, and I‘m not ashamed to admit it.

Most of the people on this planet get through life on a daily basis by being carefully shielded from certain images and ideas which they find uniquely disturbing and destabilizing. Of course, if they were, in fact, immortal supermen, these images and ideas would have a very different effect. But, they aren’t immortal supermen; and neither are we.

So, some of the images you will see in this presentation, should you choose to stay, may be unsettling or even frightening. I do not apologize for this; I believe they are essential to communicate understanding and are, in fact, the only way to communicate that understanding effectively. So, if you are likely to be disturbed by images of death and decomposition, I suggest you make your exit now. You’ve been warned.

Finally, I want each of you to understand that I believe cryonics is the most powerful and humane idea in the world today, and I treat it as such. I don‘t ask you to do the same (yet), but I do ask you to understand and to respect that this is my perspective, and I have the floor. I do not suffer fools gladly and a good part of what I have to say today is the direct result of people tolerating fools and foolishness in cryonics.

SLIDE 2

It is impossible to understand what I have to say without understanding something of who I am and how I got to be that way. It has been said that a happy childhood is the worst possible preparation for life, and I can certainly attest to that. I grew up in a stable and secure environment; I lived in the house my grandfather had built and in which my mother had been born. While my parents were working class, they afforded me everything necessary for good intellectual and emotional development. As an only child in a loving extended family, necessities were assured and an enriched environment was a given.

SLIDE 3

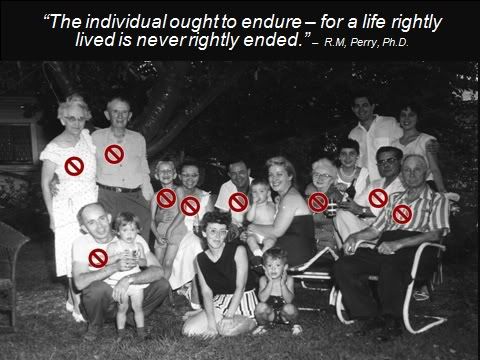

Unfortunately, the one thing my parents and extended family could not protect me from was the reality of the inevitability of disease and death. My parents were in their mid-30s when I was born, and a consequence of this was that my grandparents and aunts and uncles began to suffer age associated morbidity and mortality when I was still young and most of them had died by the time I was a pre-teen.

The red symbols above indicate people who are now dead, many long dead. I‘m the babe in arms sucking his thumb. While my mother (holding me) and my father (who took the picture) are both still alive, my mother has descended into the dark hell of Alzheimer‘s disease. Several of the people still alive from the day in 1956 when that photo was taken are in failing health and will soon be dead. [Note: both of my parents died in November of 2011.]

The impact of these lost lives on me as a child was immense and terrifying and I soon came to the conclusion that, as Mike Perry has so eloquently put it, ―The individual ought to endure – for a life rightly lived is never rightly ended.

SLIDE 4

A particularly traumatic event, and one that was to shape my life, occurred when I was ~ 8 years old. I discovered my maternal cousin, Rae Rohrman, with whom I was very close, dead in her home a few doors down the street from where we lived. Rae was a non-compliant diabetic who died suddenly during the summer and was not discovered until I entered her home approximately a week after her death. She was in an advanced state of decomposition and there were none of the considerable resources or “contexting” of the mortuary industry or the church to soften the hard reality of what death really is.

It is an ugly, destructive process and in confronting it I began to realize that the mystical explanations I was being given as to why it was both necessary and good were merely a coping mechanism adults used to stop themselves from going insane, a version of Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy for grownups which someone, someone quite human, had made up to keep the world as barely sane and orderly as it was. It was crystal clear to me that no one in their right mind would want what I saw had happened to Rae, to happen to them.

SLIDE 5

“That event and the deaths of others close to me, launched on me a quest to find a way to halt decomposition, and, shortly thereafter, to prevent death. I began experimenting with ways to interrupt and restart life processes in plants, insects and small vertebrates (red eared slider turtles) by cooling and freezing. In 1966 I was introduced to cryoprotectants and to tissue culture, and by 1968 I had amassed a substantial amount of experimental expertise and results. It was clear to me that cryopreservation offered the most likely path to achieving suspended animation.

With suspended animation would come two great boons: the ability to travel to distant star systems and explore the universe, and the ability to enter a state of indefinitely long waiting if death threatened. While I did not foresee reversal of aging or the application of this technology after so-called death had occurred, I found it enormously reassuring that death and decomposition could be forestalled, essentially indefinitely, and that even if experiencing life was not possible forever, in theory, avoiding death was.

During the course of a science fair project in 1967 entitled, ‗Suspended Animation in Plants and Animals‘ I was handed a newspaper clipping that introduced me to the idea of cryonics by telling the story of one Professor James Hiram Bedford who had been frozen after “death” to await a cure for his cancer, as well as rejuvenation from old age, to a state of healthy vigor.

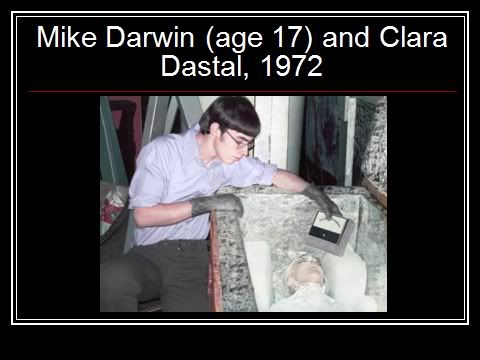

SLIDE 6

I promptly contacted the various cryonics organizations extant at that time, and quickly joined the Cryonics Society of New York (CSNY) as a suspension member, taking jobs mowing lawns and doing yard work to pay for my life insurance. In 1972, while visiting CSNY on my secondary school holiday, I was asked, along with a young graduate student, Corey Noble, to perfuse and freeze a CSNY member, Clara Dostal, who had been pronounced legally dead a few hours earlier.

I was 17 at the time and had already amassed a considerable amount of hands-on experience in cryonics. This event, as you shall see a bit later, also had a profound emotional and intellectual effect upon me.

THE PROBLEM OF PARADIGM CHANGING IDEAS

SLIDE 7

The beginning of cryonics is probably best dated to the publication of Robert Ettinger‘s The Prospect of Immortality in 1964. This date is important because it provides context for much that was to adversely affect cryonics, so you should keep it in mind as we proceed.

SLIDE 8

I did not live in a vacuum, and my interests in science and coming developments in technology was keen. I was an avid reader of classic 1950s-60s science fiction as well as popular and “hard” science publications and books. In 1968 my country was the richest and most technologically sophisticated in the world, and it was about to land a man on the moon, and return him safely to earth.

In fact, it was about to land a number of men on the moon and recover them all safely. At that time, the United States (US) Federal Government was funding the National Aeronautics and Space Administration to an unprecedented degree. Not since the Manhattan Project had so much money and effort been expended upon a scientific undertaking.

A world view emerged from this effort, and it was a world view promulgated, endorsed by, and made completely credible to the populace by the US government. That world view was one that posited as inevitable the construction of a large, orbiting space station, the establishment of a permanent lunar base, and the beginning of the expansion of humanity into the solar system – and more speculatively, beyond.

This worldview is best summarized and most accessible today in the first half of the film 2001: A Space Odyssey which premiered in 1968, the year I was becoming deeply involved in cryonics. While the film was undeniably science fiction in its premise of encountering extraterrestrial life, it‘s technological predictions of what life would be like at the turn of century were universally considered completely reasonable by far sighted and respected scientists and futurists – even conservative ones such Dandridge Cole and Isaac Asimov.

That world, 33 years in the future, became my model, and the model for millions of other thinking people, young and old alike, for how the future would be. It was a world where space colonization was underway, life spans had been modestly extended, human hibernation was a reality and solid state organ cryopreservation was in use for storing transplanted organs. It was a reassuring view of the future, and in particular of my future, if I didn’t die before getting there.

SLIDE 9

By 1976 I was becoming uncomfortably aware that the future I expected was not materializing at a rate consistent with the worldview in 2001. Organ cryopreservation programs had been abandoned in all but one facility in world, the US manned space program was doomed, and interest in serious, interventive gerontology, let alone meaningful research, was nil.

The money and intellectual resources required to achieve these goals had been redirected to an endless series of wars, first in Vietnam and later in the Middle East and East, as well as a succession of botched and unsuccessful programs to end poverty in the US (the Great Society), cure cancer, and deal with longstanding mishandling of the environment. The spending spree of the latter days of the Cold War bankrupted the Soviet Union and, in truth, bankrupted the West, as well. The focus of the planet‘s population was on protecting itself against bogeymen of its own making and it spent and spent maniacally to create weapons systems of vast lethality and ever increasing complexity.

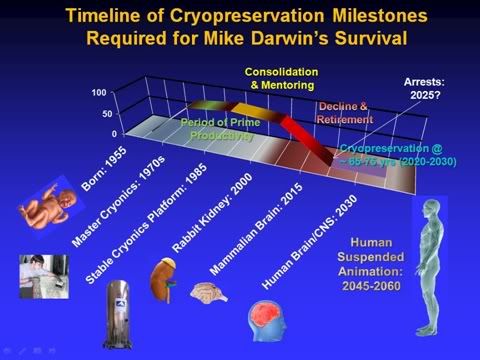

So, sometime in late in 1976 I wrote out a timeline of milestones that I thought would be necessary if I were to survive. This was a simple list of critical achievements with the dates by which they must be accomplished alongside them. It took a conservative and probably all too unfortunately realistic prediction, of the likely arc of my productive life.

While it has proved a more accurate road map than my naive first imaginings of my future, it too has fallen short and has proven flawed, perhaps fatally flawed. Since I was not then, nor am I now, either poorly informed about cryonics or lacking in real world experience in its practice, I suggest you might want to pay careful attention to what went wrong with this very conservative timeline, because it very likely has important implications for your future as well.

SLIDE 10

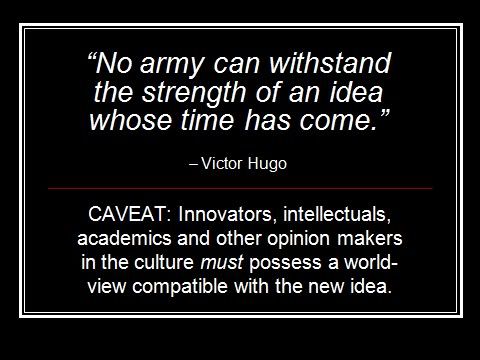

This quote, suggested by Robert Ettinger for the opening of Robert Nelson‘s book We Froze the First Man, was meant to imply that the success of cryonics was inevitable meant to imply that the success of cryonics was inevitable – that it was an idea whose time had come. Victor Hugo was an idealist, and a man who had the good fortune to live in an age where the time had indeed come for most of the ideas he cared passionately about and championed.

Overlooked by Ettinger was that powerful, paradigm disrupting and socially inflammable ideas require careful preparation of the culture before they can flourish. No thinking person would imagine it possible to arrive in a Stone Age culture, such as the Pirotribe, in the Amazon basin, and begin discoursing successfully on Quantum Electrodynamics or Natural Selection. The dismal experience of Western Christian missionaries (and of their “flocks” ) with African and Polynesian cultures similarly points to the futility of attempting to convert an unprepared culture to ethical or ideological standards that are alien to their environment and destructive to their culture and their entire way of life.

SLIDE 11

SLIDE 11

While applied engineering and electronics were undergoing explosive advances in 1964, the biological sciences lagged far behind. In the medical, biomedical and cultural context of 1964, the year Ettinger‘s The Prospect of Immortality was published, the discovery of the structure of DNA was only 11-years old, CPR was only 4-years old, the Uniform Determination of Death Act would be not be passed until 1978 (14-years later), the first heart transplant was 3-years in the future (1967), and most of the United States had no emergency medical system (EMS): ambulances were hearses driven by Funeral Directors.

Some Definitions “Culture“: The sum total of values, norms, assumptions, beliefs and ways of living built up by a group of people and transmitted from one generation to another.” Innovation: “The adoption of a new practice, process, or paradigm by a community —not just a new product or service. “Creativity“: To cause to come into being, as something unique that would not naturally evolve or would not exist via ordinary processes. Resulting from originality of thought.”

SLIDE 12

To understand the impact this primitive state of affairs in the life sciences was to have on the launch of cryonics, it is first necessary to examine the way scientific advancement proceeds in a culture, and in order to do that we must define some key concepts. Culture: The sum total of values, norms, assumptions, beliefs and ways of living built up by a group of people and transmitted from one generation to another. Innovation: The adoption of a new practice, process, or paradigm by a community — not just a new product or service. Creativity: To cause to come into being, as something unique that would not naturally evolve or would not exist via ordinary processes and resulting from originality of thought.

SLIDE 13

There are, fundamentally, two types of new ideas: Conventional: incremental innovations, with a high likelihood of success and a modest return on investment and Radical: (Paradigm Changing): favoring or effecting fundamental or revolutionary changes in current practices, conditions, or institutions with a low likelihood of success and a large return on investment.

SLIDE 14

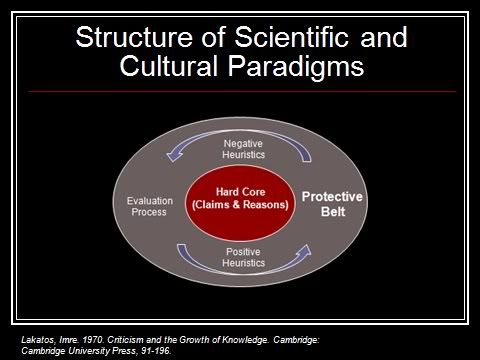

In the early 1970s, again well after cryonics had attempted to launch, the philosopher and historian of science Imre Lakatos created a new model for how scientific change occurs. He posited that scientific advance proceeds on two fundamental and very different levels. Most of scientific and technological progress is incremental; it involves testing and validation or invalidation of the dominant scientific paradigm of the age.

For instance, in a world where the earth is presumed to be the center of the universe, all astronomical work will consist of the careful accumulation of information designed to support this view and to reconcile observed phenomenon with the core tenet that the sun, and other heavenly bodies, revolve around the earth.

At some point, discontinuities in the observed data may lead to an alternative paradigm; one completely add odds with, and antithetical to, the accepted explanation (theory) of how the universe works. This second type of progress is not incremental, but rather is revolutionary: it overturns the entire structure of the previous paradigm. It penetrates the protective belt of gentle scientific inquiry and smashes the hard core of the existing paradigm.

We tend to forget that scientific ideas do not exist in a moral, social or philosophical vacuum – or in a political one, for that matter. Scientific theories such as how the solar system is organized, how old the universe is, and how life arose and became diversified, inform human beliefs about their purpose and their place in the universe. And, they impact the complex web of powerful social institutions that create and enforce philosophical and behavioral norms.

The Copernican theory gutted the authority of the Catholic Church and, to a significant extent, of the Christian religion, because it challenged the veracity of these institutions‘ teachings – teachings which, in order to hold moral authority, had to be absolute and infallible.

SLIDE 15

So, the success of novel ideas depends upon more than their being provable by observation or demonstration; they must also have compatibility with fundamental philosophical, moral, ethical, social, and political paradigms of the culture, and, of course, be technologically and economically feasible. They must also, critically, have credible, articulate and aggressive advocates.

SLIDE 16

As it turns out, there are, very broadly, two ways that paradigm changing ideas can be introduced into cultures. The first and easiest is by SEDUCTION: Incremental (limited) powerful desire for benefits absent any understanding of understanding of detriments (including destruction of the existing order). The second way is by INSURGENCY: Organized, forceful and determined effort to establish a new paradigm by subversion of the existing order.

SLIDE 17

Perhaps the best example of introduction of an idea by seduction is that of agriculture. Sometime between 100,000 and 80,000 years ago, humans began to make the transition from a hunter-gather life-style to agriculture. Today, we take agriculture for granted and we by and large uncritically accept it as an unblemished good.

However, the goodness or desirability of agriculture is hardly the picture of universal plenty that comes to mind when the word is uttered today, 100 or so millennia after agriculture was invented. In the context of hunter-gather society, agriculture was an unmitigated disaster that completely destroyed their culture, religion, way of life, and ultimately, much of their health and well being.

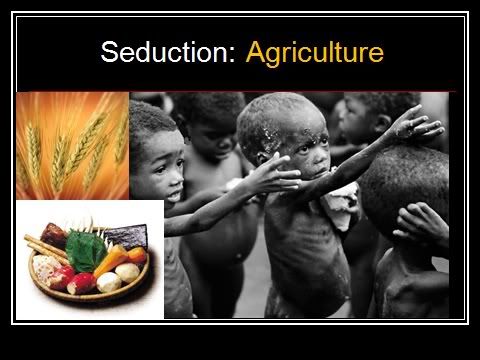

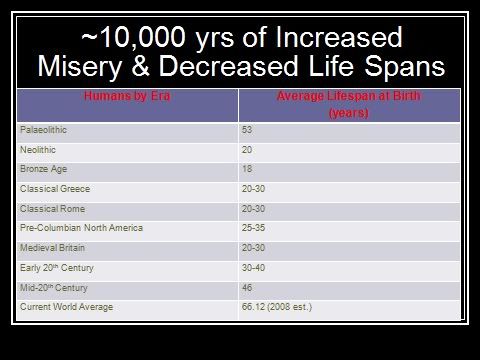

SLIDE 18

Hunter-gatherers controlled their population size, lived in small intimate groups, and were constantly on the move. Because they moved frequently they did not ingest or come into contact with their own wastes, or the wastes of the animals they fed from. They lived their entire lives in the open air under uncrowded conditions, and they ate a nutritionally diverse diet that was almost completely devoid of empty calories. As a result, they had little or no communicable infectious disease: no typhoid, cholera, or other water borne illnesses that result from fecal contamination of the drinking water supply.

In addition, group size was far too small to sustain communicable epidemic diseases such as smallpox, measles, mumps and tuberculosis (TB). TB, in particular, is an urban disease that requires close quarters and poor ventilation to be self sustaining and epidemic. It is also a zoonotic disease: one acquired from living commensally with animals – a necessary facet of agricultural life.

The quality and quantity of the hunter-gatherer life was thus both surprisingly high and long. Paleolithic man appears to have had a mean lifespan of between 45 and 53 years. Morbidity was brief and death came suddenly from misadventure or homicide. With the advent of agriculture during the Neolithic, life spans plummeted and remained well below hunter-gatherer levels until the first decade of 20th century in the US, and not until mid-century, globally.

SLIDE 19

The toll exacted by agriculture in terms of human suffering was immense. Agriculture allowed for a rapid expansion in the number of humans at the cost of hunger, starvation and an almost unimaginable disease burden. Cities became not only possible, but necessary, and up until the 19th century they were veritable killing machines which sucked in the surplus population generated by satellite farming communities and killed them off with infectious disease and dangerous working conditions. Cities did not become self sustaining in terms of population until late in the 18th century!

It seems clear that if our hunter-gatherer ancestors understood that agriculture would virtually exterminate their way of life, and create millions and even billions of starving and dispossessed people, they would have fled from it and burned the first would-be farmers alive. This didn’t happen because the immediate benefits of agriculture were so overwhelming: the ability to create a steady, seemingly reliable supply of food in superabundance was incredibly seductive.

Seeing the downsides was a virtual impossibility for people in those circumstances who lacked the scientific method, lacked the written word, and had little experience with new ideas or rapid change.

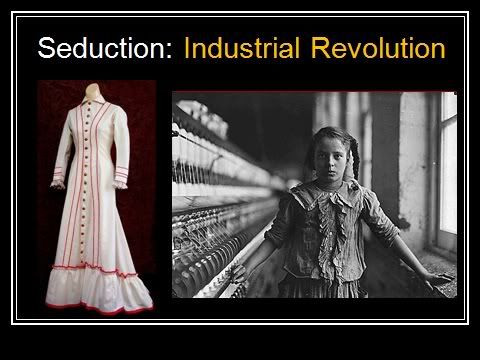

SLIDE 20

A similar state of affairs pertained in the late 18th and early 19th centuries when the Industrial Revolution began. The Industrial Revolution allowed for the prodigious production of high quality goods on a scale previously unimaginable. It created a cornucopia of wealth allowing the average man, and even the poor man, to enjoy goods and services that previously royalty, or the richest of the elite, could not have purchased at any price. The human cost of this was, again, very high: child labor, dangerous working conditions that crippled and maimed, and a reduction in air and water quality that killed thousands at a time often in the space of few days.

SLIDE 21

And again, as with agriculture, the Industrial Revolution was a fiat accompli before our species began to understand the adverse global environmental impact and come to the realization that the whole foundation of technological civilization was not sustainable. Hunter-gatherers lived in ecological balance with their environment; technological man cannot. To sustain ever advancing technology man must expand his environmental horizons into the solar system, and beyond.

SLIDE 22

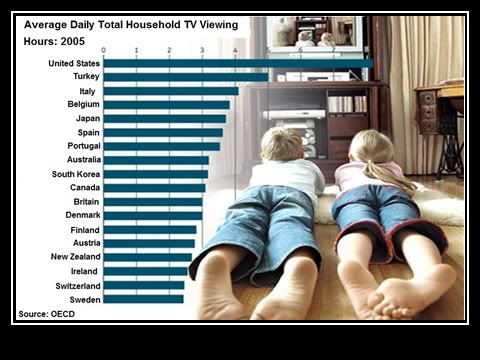

Finally, telecommunications are an example of paradigm changing scientific advance operating via seduction.

SLIDE 23

Within my lifetime TV, mobile phones, and the Internet have transformed the culture and degraded or destroyed some of its more cherished institutions.

SLIDE 24

This tableau is how I grew up: the evening family meal taken in a stereotypical fashion with lots of opportunity to talk and socially interact with both my parents, and with members of my extended family. It was not understood by any of the participants to be a critical element in a cohesive and functional family life – it was just something everyone did and took for granted. But, in fact, it was (and is) a critical tool for facilitating communication, and allowing time and the proper conditions, to reflect on the day‘s events and consider what was necessary to be done tomorrow.

SLIDE 25

This slide lists but a few of the social and cultural sea changes caused by telecommunications with a high profile casualty being that family meal together, where people with comparatively uniform values and experiences communed with each other.

SLIDE 26

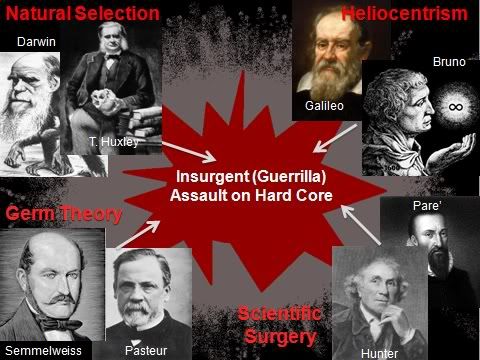

Not all novel paradigm changing ideas are seductive. Many are immediately and rightly perceived by the culture to be dangerous to the established order; ideas which can overturn political and social control mechanisms and completely disenfranchise, or even destroy bedrock institutions.

Because ideas about biology and medicine impinge upon the territory of religion in explaining man‘s purpose in the universe, and also on providing comfort and succor to the sick and dying, they are particularly scrutinized areas in terms of their compatibility with the hard core of the existing scientific paradigm – a paradigm in which the culture and its most powerful institutions are heavily invested.

Natural Selection, Germ Theory and Scientific Surgery created serious threats to the existing order that were immediately appreciated.

All of these ideas challenged the traditional view of Vitalism, and were steps towards “reducing” man, and indeed all living things, to the status of mechanisms: clockworks that could be rationally explained, understood and eventually manipulated at will. These novel ideas had the power, at least in theory, to confer on men the knowledge and ability formerly reserved only for god. If life was a natural phenomenon governed by the same physical laws that enabled the construction of timepieces, factories, bridges and manufacturing machines, what was to stop man from creating life itself and, in essence, usurping the role of god?

Insurgent attack on the hard core of critical paradigms is dangerous…

SLIDE 27

The culture quite rapidly comes to understand that such ideas are exceedingly dangerous and almost invariably takes extra-scientific steps – social, political and economic – to protect the existing paradigm and defend its hard core at almost any cost. The fate of Galileo for promulgating Heliocentrism is a classic case in point. And Galileo was lucky – extremely lucky. His fate was to be forced to recant his heretical ideas and spend the remaining years of his life under house arrest.

SLIDE 28

By contrast, consider the fate of Giordano Bruno, the Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, mathematician and astronomer, who is best known as a proponent of the infinity of the universe (his cosmological theories went beyond the Copernican model in identifying the Sun as just one of an infinite number of independently moving heavenly bodies: he is the first European man to have conceptualized the universe as a continuum where the stars we see at night are identical in nature to the Sun).

He was burned at the stake by the authorities in 1600, after the Roman Inquisition found him guilty of heresy. Challenging the hard core of critical scientific (and thus social, cultural and political) paradigms is dangerous and often deadly…

THE INHERENTLY DISRUPTIVE CHARACTER OF CRYONICS

SLIDE 29

…and at the very least it is inconvenient, incredibly unpleasant, and costly.

The real reason the Dora Kent drama played out was that cryonics, practiced well (optimally) caused extreme cognitive dissonance in the medical and legal authorities in the community in which we were operating. Over and over again they kept badgering me with the statement that, “Two minutes was NOT long enough to wait after cardiac arrest before starting cryonics procedures.” To which I responded repeatedly, “Well then how long is long enough? How dead does someone have to be before it is OK to start working on them? You define death as when cardiorespiratory arrest occurs; you say nothing about what can or should be done afterwards.” They found that enormously disconcerting and it made them angry, really angry.

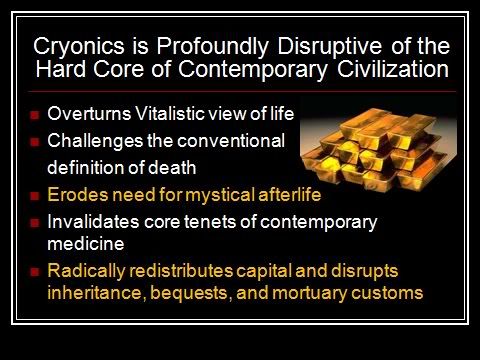

SLIDE 30

So, if we look at cryonics objectively and in the context of this culture and this civilization at this time, then cryonics is just about the most disruptive and threatening idea that has ever come along. Unlike Natural Selection or Germ Theory, or even Heliocentrism, cryonics will inevitably overturn the Vitalistic view of life, challenge the conventional definition of death, erode the need for a mystical afterlife, invalidate the core tenets of contemporary medicine, and radically redistribute capital and disrupt inheritance, bequests, and mortuary customs!

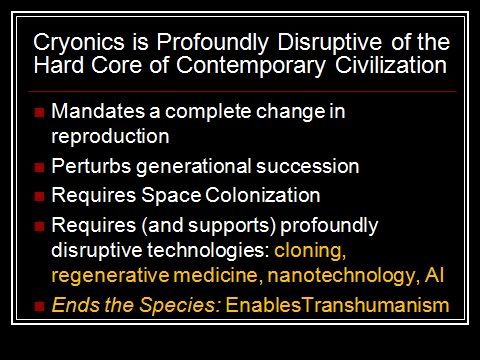

SLIDE 31

What‘s more, it mandates a complete change in reproduction, perturbs generational succession, requires space colonization, requires (and supports) profoundly disruptive technologies such as cloning, regenerative medicine, nanotechnology, and AI, and most frighteningly of all, it Ends the Species and enables Transhumanism.

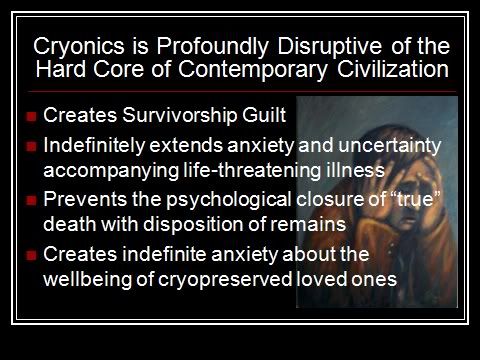

Cryonics is Profoundly Disruptive of the Hard Core of Contemporary Civilization Creates Survivorship Guilt; Indefinitely extends anxiety and uncertainty accompanying life-threatening illness; Prevents the psychological closure of “true” death with disposition of remains; Creates indefinite anxiety about the well-being of cryopreserved loved ones.

SLIDE 32

Beyond these inevitable long term effects, cryonics has a number of poorly appreciated (by cryonicists) severely psychologically damaging adverse effects. As Curtis Henderson once observed, “All biographies end in tragedy; everybody dies. Always.” A consequence of this is that no one need feel guilty about living – in the end we all end up dead – there are no survivors.

Cryonics changes that, because people now living have an opportunity to possibly ‗cheat‘ death, and that means that if they choose to do so and succeed, they will have to face the prospect that they did not act quickly enough, or aggressively enough, to save the lives of all their other loved ones who have died or will die and not be cryopreserved. This survivorship guilt can be crippling, and in some cases all consuming – but at the very least, it is always painful.

One of the few advantages of death is that it is final. It puts an end to the suffering and anxious uncertainty that must inevitably accompany life threatening illness. Anyone who has agonized over the fate of a loved one in the Intensive Treatment Unit (ITU) can at least begin to understand the psychological impact of stretching out that period of uncertainty over a lifetime, and beyond.

The devastating effects of this kind of limbo are often seen in cases where children are abducted and not found, or soldiers are lost in battle, but no remains are recovered. Cryopreservation prevents the psychological closure of ‗true‘ death with disposition of remains and creates indefinite anxiety about the well-being of cryopreserved loved ones. Cryopreserved people are not put away in a cemetery where no further harm can come to them. Rather, they require indefinite care, vigilance and protection. This is often a source of extreme anxiety in survivors.

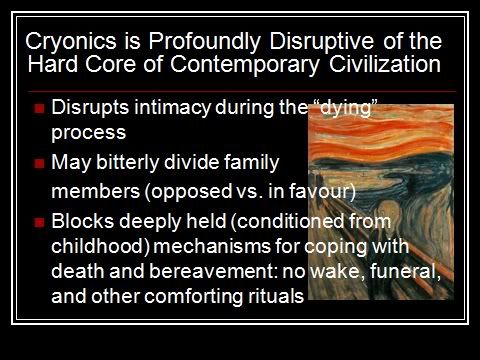

SLIDE 33

These immediate detrimental effects of cryonics become intensified during the terminal phase of a cryonics patient‘s life. The presence of the Standby/Stabilization team and their equipment and supplies disrupts intimacy during the “dying” process, may bitterly divide family members (those opposed vs. those in favour), and block deeply held (conditioned from childhood) mechanisms for coping with death and bereavement: no wake, funeral, and other comforting rituals.

With the understanding of these general and largely unavoidable obstacles, we are now prepared to examine in greater detail the specifics of why cryonics failed to launch in 1964.

End of Preface and Initialization Failure, Part 1

Excellent. It will take me time to digest this, but I have two questions. The biologist Jean Rostand wrote a preface to “The Prospect for Immortality” and in his essays I found Rostand humane and forward-thinking. Did he continue to support the idea of cryonics?

Also we have some parallel life history. I grew up in the house my great great grandfather built, surrounded with the personal possessions and writings of my ancestors, unusual in Sydney but not in rural areas, with nearby extended family and with a tradition of vigorous dinner table discussions on just about any topic. A friend died in a skiing accident when I was seventeen, whereupon I left the church and felt it was wrong for him to have been thawed out and cremated.

I met Thomas Donaldson and talked with him about cryonics in 1976 at the time the person giving technical help for my research project at university committed suicide because of the death of her husband. Already I was writing two major research essays on aging and regeneration of tissues (important biological problems, I thought) and so it was easy to slot in a third on cryobiology. To what extent do our early encounters with death affect our acceptance of the prevailing society views of it?

Rostand’s story, if I my understanding is correct, is a very sad one. What I have been told (and this is 3rd hand) is that he was very disappointed and possibly even disgusted with the way cryonics evolved after Ettinger’s book was published in 1964. Anatole Doilinoff told me that he and Rostand “did not get on.” This would be completely understandable since Dolinoff, who was a pleasant enough and hospitable man, was also just short of barking mad. I spent several days as a “prisoner” in his chateau outside Paris. His hospitality was lovely, the food was delicious, and he shuttled me to the Louvre and Versailles. However he was controlling, often irrational, and spent well over 16 hours arguing with me about why cryonics would NOT work, all the while recording this discussion on tape. Since he spoke no English, translation was required in both directions. I was exhausted and drained when I “escaped” to the next leg of my journey. It is my belief that much of the resistance and backlash to cryonics which occurred in France was due to the crazy and irresponsible actions of men like Dolinoff and Martinot (both father and son). I have been told that Rostand became increasingly unhappy/dissatisfied with this state of affairs as the years went by. When cryonics was effectively outlawed in France in the 1970s, Rostand reportedly became bitter and fully disillusioned. Towards the end of his life he denounced cryonics publicly. Rostand died on 4 September, 1977.

Rostand is not well known in the US, however on the Continent he is regarded as an influential humanistic philosopher who sought to integrate biology into the world of the social sciences. His philosophical books alone number over a dozen, based on the count on my bookshelf. He published at least 15 major scientific books, most on embryology and parthenogenesis. Extending on the work of Jacques Loeb and Ernest Just with sea urchins, Rostand was the first to demonstrate induced parthenogenesis in a vertebrate – the toad Xenopus laevis [C R Seances Soc Biol Fil. 1951 Oct;145(19-20):1453-4.[Experimental parthenogenesis in Xenopus laevis. ROSTAND J.]. I met several of Rostand’s former graduate students when I was in Paris in the early 2000s. He was apparently revered by his students and colleagues alike, and was considered one of the leading intellectuals, scientists and humanists in France in from the 1950s on. There is even a secondary school named after Rostand in France.

These are some of my favorite Rostand quotes:

“I should have no use for a paradise in which I should be deprived of the right to prefer hell.”

“A few great minds are enough to endow humanity with monstrous power, but a few great hearts are not enough to make us worthy of using it.”

“It is not easy to imagine how little interested a scientist usually is in the work of any other, with the possible exception of the teacher who backs him or the student who honors him.”

“A body of work such as Pasteur’s is inconceivable in our time: no man would be given a chance to create a whole science. Nowadays a path is scarcely opened up when the crowd begins to pour in.”

“God, that dumping ground of our dreams.”

“I still understand a few words in life, but I no longer think they make a sentence.”

Rostand made many scientific predictions, most related to biology (he authored at least 4 books on the subject). I reproduced his most significant ones, and highlighted those that have happened. With the advent of modafanil it is now possible to overcome fatigue and, arguably, the later generations anxieolytics fulfill his prophecy about the pharmacological control of anxiety (I personally consider it a done deed – enough alprazolam and it is virtually impossible to feel anxious about anything ;-)):

* Parthenogenesis, reproduction through development of an unfertilized gamete, will someday be possible, so that we will be able to have as many exact copies of an exceptional individual as we want.

* Science will be able to reprogram gametes by changing the composition of the nucleic acids that determine heredity, thus modifying an embryo at its start.

* Animals might be “humanized.” For instance, human bone marrow could be transplanted into apes so that they would produce human blood. Human hormones could be introduced into an ape to increase its intelligence. Treatments could be performed on ape embryos to increase the number of cortical cells in the brain, and thus increase intelligence.

* It is possible that human beings will be able to create life artificially, though not in the near future. Rostand says, “By manufacturing that humble assimilating and self-reproducing particle, by causing life to be born, for the 2nd time, of something other than itself, man will have closed the great mysterious cycle. A product of life, he will have in turn become a producer of life.”

* Through chemicals, such things as fatigue, anxiety, and grief will be alleviated, and pleasurable emotion will be available on demand. Control of feelings, opinions and ideas will be possible, as will the replacement of memories.

To me, Rostand is a tragic example of a massive opportunity for the acceptance and advance of cryonics in a society having been utterly demolished by irresponsible nutters. Not to mention at the expense of Rostand’s own possible chance at continued personal survival. Along with Rostand, the well respected scientist and cryobiologist Pierre Boutron was once in public sympathy with cryonics, and Boutron has even published a book arguing for an aggressive research effort to halt aging titled Arrtons de vieillir. My understanding is that Boutron has also publicly renounced or denounced cryonics. — Mike Darwin

Thank you, thank you for your summary of Rostand. In my mind he was the “big one” that got away, and I am much saddened by this. He could have given cryonics the biological and philosophical credentials it so badly needs, and because his father was such a respected writer as well, an entree into the arts. So many of the other celebrities, and I sort of include science fiction writers here, who were interested in cryonics were part of the entertainment industry, and perhaps cryonics has languished in this industry a bit too long. Again, thank you but I am sad.

I wish I knew more about Rostand. I tried to meet with some of his colleagues, but I was in Paris for only two days and having a miserable time of it. If you don’t speak French and you are American and not well to do, the Parisians can (and do) behave abominably. I had no incentive to prolong my stay. Rostand is a tragedy, because his writing celebrates life and the potential for “the biological revolution” to transform it in a positive way. By all accounts, he genuinely wanted to live indefinitely. Two other remarkable intellects come to mind in this context; Dandridge Cole and Arthur C. Clarke.

Cole is virtually forgotten today and that is a tragedy in and of itself. The man was a giant – a prodigious intellect who thought about and sought ways to use to use technology on a grand scale and with adventurous abandon. Cole would have loved Thomas (Donaldson’s) ideas for building particle accelerators the size of Jupiter – or bigger. Most people know about Gerard K. O’Neill’s idea of building space habitats at L5. Cole was the father of the idea of the rotating cylinder; the interior of which would be terraformed with lakes and streams and forests… But, unlike O’Neill, Cole was the better engineer. He understood the problem of cosmic and solar background radiation and his proposal was to liquefy asteroids using focused solar energy (mirror arrays) and then blow the molten rock up like a balloon with gas. The result would be a self-shielded cylinder which could then be inhabited. I find Cole’s books as fresh and exciting today as I did when I read my first one sitting on Curtis Henderson’s front porch on Long Island ~40 years ago – though Mark Plus would probably classify them all as hopelessly Paelofuturistic rubbish :-). Cole died of a heart attack at age 44 in 1965. His relatives decided against cryopreserving him, even though that was his stated wish – he was one of the few scientists of high credibility to publicly support cryonics.

Arthur C. Clarke was considerably more than a science fiction writer – he was a first class mind. While he was lousy at technological forecasting, he did invent the communication satellite, and for that I am deeply grateful because it has made GPS navigation and DIRECTV possible – both of which have made life much, much easier and enjoyable for me. I corresponded with Clarke briefly after the Dora Kent debacle. He provided a deposition arguing against her removal from cryopreservation. Clarke rejected cryonics in a seemingly very nonchalant way. I’m not sure even to this day that I understand it. He had “retired” to Sri Lanka where he lived in abundant comfort, fully connected to the world via his own invention hovering overhead 20,000 miles out in space. He was well supplied with both close friends and the Sri Lanken lads he fancied. And therein might be the only clue, because he remarked in his last letter that opting for cryonics would mean leaving his beloved Sri Lanka, and that was something it seemed apparent he was unwilling to do. One of the many, many grievances I have against mortality is that I will almost certainly not be alive to read Clarke’s personal papers and his diaries, which are sealed until 2038. It may be that his thoughts on cryonics and the “meaning of life and death” are more fully articulated there.

By all accounts, and I do mean all, Clarke was a profoundly good and decent man who was known for his generosity and his kindnesses. This is in sharp contrast to both Heinlein and Asimov, who I have heard, first hand, some most unpleasant stories about. [Several women who knew Asimov, either professionally, or through Fandom have told me (and others) of his abusive behavior.] Clarke’s vision of 2001 is a hauntingly beautiful prophecy betrayed by craven fools who history will record (if we endure) as having turned their backs on their future and their destiny. Clarke was no Rostand, and I think his having chosen cryonics for himself would have made little difference in advancing the acceptance of cryonics. But that is irrelevant, because the loss of Clarke himself is a great tragedy in its own right. — Mike Darwin

Clarke to the best of my knowledge never identified himself as a “sovereign individual,” “perpetual traveler” or whatever name the libertarian four-flushers use these days to describe strategies of tax avoidance by treating nation-states like competing hotels, but he wrote about how he gamed the tax laws in Sri Lanka and saved a fortune. I have to admire him for that. ; – )

I’ve never read any of Cole’s books, which went out print long ago, and apparently no one has bothered to scan them and turn them into ebooks; but from what I’ve heard about his ideas, I wouldn’t necessarily consider them from the “paleofuture.” I think Peter Thiel has identified a proximate reason for why a lot of feasible things haven’t happened in the past 40 years: Many forms of engineering have become effectively illegal, especially involving energy supplies, transportation, aerospace and biotechnology. Computing got an exemption, at least for now, so we’ve seen rapid progress in that area, though often with meretricious results like Facebook. If Cole had gone into suspended animation in 1965 and awoke now, he would find the internet , smart phones and tablets thoroughly amazing, along with medical imaging, genomics and other technologies given a boost by faster computing; but he would have trouble understanding why the U.S. sent only a few people to the moon and then stopped 40 years ago, or why we don’t have faster air travel than we had in the 1960’s, or why we have let the postwar infrastructure he remembered as all shiny and new fall into ruins.

As for Asimov & Heinlein, do you think their writings have aged all that well? What would people born since 1990 get out of them? Think of the weirdness of science fiction’s history in the past 100 years: People who read SF before the late 1950’s thought that manned space travel might happen long after their lifetimes, except for the ones who lived to see the moon landings come and go in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. Now the young people who read SF view manned space travel as something which sort of happened in their parents’ and grandparents’ generations, but not in theirs, kind of like a “Mad Man” thing. (As I recall, in one episode Pete Campbell geeked out when he got to meet some NASA scientists on a business trip for his advertising firm.) Asimov and Heinlein, along with Clarke, did the bulk of their writing on the wrong side of the failed “space age” to seem all that relevant today.

I agree completely with Thiel’s observation – it is one I’ve been pounding away at for onto 2 decades as it applies to biomedical technology. When the FDA was granted regulatory control over medical devices, it was like a total, indefinite solar eclipse. No one in the West has any idea what this did to medical device innovation. Several years ago I was in China, and I saw medical devices right out of science fiction. They were all diagnostic because that’s an easy platform to exploit and the West has capitalized the initializing technology with its demand for consumer electronics. Unfortunately, the Chinese are not yet rich enough to be doing such clever things with implantable devices on a large scale. But, if you want a tiny, cheap ultrasound unit that uses your laptop to process the image and display it, then they’ve got it. As well as a replacement for the stethoscope, which is a small device that displays the ECG, delivers high fidelity sounds with an indication of depth, and which processes and identifies many cardiac and respiratory sounds. It also does basic arrhythmia recognition.

Can you imagine if medical devices and diagnostics had been allowed to progress to where Suri and smartphones are today? Medicine is incredibly algorithm driven – you can see to what extent this is so if you’ve ever had access to Silver Platter, or other mini-AI diagnostic programs. And the more quality, objective data you have, the more mechanical the differential diagnosis becomes. The catch is, you have to be smart enough to use the technology. It fascinates me that in cryonics, for instance, there is essentially no use of telepresence, no in-field computerized data capture, and very little manual data capture. I would literally have cut off a finger to have been able to have a highly competent expert present with me on cases in the field, or even in the operating room. The level of medical knowledge present in cryonics is minute, and yet there is no use of this phenomenal technology to bring expertise to the field, or to the OR.

As to Cole, I don’t know if he would be amazed by computing or consumer electronics, but I agree wholeheartedly he would be astonished by the lack of progress of in the bread and butter world of macro-engineering. One thing I’m conning to believe is that, in addition to the choking effect regulation has, another reason why progress stalls is likely that societies and civilizations are just like individuals – they only have so much attention bandwidth. The group mind can only focus and act upon a comparatively small number of ideas or issues, and a few of these will tend to dominate at any one time. For instance, there is always some absolutely abhorrent thing that societies are preoccupied with. Once it was miscegenation, at another time it was drink, in the 1970s it was drugs and today it is pedophilia. God help you if your vice is the cause du jour. That phenomenon says something powerful about the way the uber-mind of a civilization works, because it is almost always fairly tightly constrained. That intensity of focus very likely blinds a large fraction of the individuals in a society to other endeavors and it surely sucks up and concentrates the resources, such that those who are interested in broader pursuits find it difficult to pursue them. Now, here’s the 50 million dollar question: how many ideas does the uber-mind typically deal with at any one time, and does that number scale in any way with the size of civilization?

My bet is that the number of ideas is small, and that integrating relatively isolated societies into a larger civilization COLLAPSES the number of ideas to about the same number as it is for any given group above a certain size. I wouldn’t be surprised if a civilization of 300 million can effectively hold in its attention any more ideas than can a town of 5,000 people. If that’s true, then flattening the world really does mean FLATTENING the world. One thing I notice in traveling is the increasing homogenization of cultures around the world. That’s sad and its boring and its yet another excellent reason to spread humanity out over vast and communications limiting distances. — Mike Darwin