By Mike Darwin

In the Beginning

Figure 1: Jerry D. Leaf with ‘Nanook,’ a survivor of 4 hours of asanguineous perfusion at ~5oC as Nanook recovers a few hours after rewarming to normothermia.

Figure 1: Jerry D. Leaf with ‘Nanook,’ a survivor of 4 hours of asanguineous perfusion at ~5oC as Nanook recovers a few hours after rewarming to normothermia.

Cryonics was not initially conceived of as a medical undertaking, per se. While there was discussion of the use of the facilities of hospitals and of heart-lung machines, extracorporeal medicine was just beginning in 1964, and the general approach outlined in Robert Ettinger’s The Prospect of Immortality was one that might fairly be described as straddling cryobiology and mortuary practice.1 The idea was itself radically new, and little attention was given to business planning, or other minutiae of day-to-day operations. A likely reason for this was that many, if not most of those who first espoused or took up the idea, expected that cryonics would become the province of large corporations and establishment medicine, as soon as it ‘caught on.’

When it didn’t catch on, the response was (not unreasonably) to proceed as best as was possible under the circumstances. And the circumstances were not good. There was little interest, and even less money, and cryonics became a strictly do-it-yourself (DIY) undertaking. With one or two exceptions, the people involved in cryonics were involved only because they wanted the service for themselves. Without exception, those who chose to become involved in actually delivering cryonics care – whether perfusion or cryogenic storage – did so only because there was no one else to whom they could turn. Since morticians lack the social standing (and thus pressure to conform) of physicians, and because they are very service oriented and skilled at dealing with disposition of the dead, they became the most willing (if still reluctant) professional partners to cryonicists. Additionally, because the disposition of human remains is governed by a considerable body of regulation, and requires licensure, the mortician, rather than the physician, became the essential professional to cryonics operations.2,3

A not surprising consequence of this was that mortuary technology rapidly came to define how cryoprotective perfusion was delivered in cryonics.4,5 The core piece of equipment was typically the Turner Porti-Boy embalming pump, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Cryoprotective perfusion using a Porti-Boy embalming machine in 1972: Mike Darwin adding pre-chilled Ringer’s solution to the pump reservoir.

Figure 2: Cryoprotective perfusion using a Porti-Boy embalming machine in 1972: Mike Darwin adding pre-chilled Ringer’s solution to the pump reservoir.

The first scientific report on what was actually being done in terms of cryopatient perfusion was published in Manrise Technical Review in March of 1973.6 This paper noted the abysmal conditions attending mortician-delivered perfusion and called for the application of a wide range of changes to improve the situation. Since I was a coauthor of that paper, I feel I can speak to the strong emotions that prompted it to be written; namely disgust and horror at the kind of care cryonics patients were receiving. I was not alone in this opinion, or in these feelings, and the people who had published this paper, Fred and Linda Chamberlain, were also hard at work on changing this situation. Attempts to interface with the nascent but rapidly growing extracorporeal medical community at that time were unsuccessful. However, one of Fred Chamberlain’s colleagues at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory happened to be an engineer who was also on hemodialysis – a truly nascent technology at that time (1972). Fred learned as much as he could from his colleague, and he and Linda also applied themselves to the few textbooks and comprehensive monographs on extracorporeal medicine that were available at the time.

The products of this effort were the Manrise procedure manual7 and the Manrise perfusion machine, shown in Figure 3. At that time roller pumps were cost-prohibitive, and the light weight, high output and small size of centrifugal pumps made them highly desirable for use in perfusion equipment that would have to be stored and used in very confined spaces inside a mobile operating room, or the preparation room of a mortuary. It would be another decade before technological advances in perfusion obsoleted, or outmoded a sufficient quantity of cardiopulmonary bypass equipment, such that quality pumps with substantial working life left to them, became available on the used or ‘surplus’ medical equipment market.

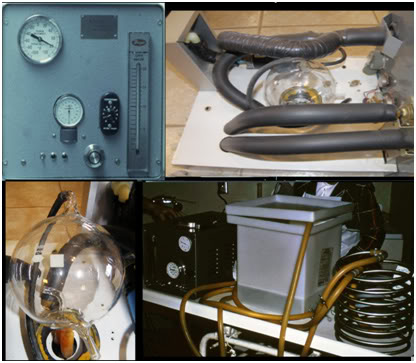

Figure 3: Manrise Model 101 perfusion machine, circa 1973: control panel (upper left), machine interior (upper right), bubble trap (lower left) and the perfusion machine with heat exchanger and reservoir (lower right).

Figure 3: Manrise Model 101 perfusion machine, circa 1973: control panel (upper left), machine interior (upper right), bubble trap (lower left) and the perfusion machine with heat exchanger and reservoir (lower right).

The Manrise perfusion machine consisted of a variable speed centrifugal pump (Micropump), a re-useable bubble trap fabricated from Pyrex glass, pressure, flow and perfusate temperature gauges, and an accompanying heat exchanger (a helical coil of ½” OD, 316 food grade stainless steel tubing). The system was sterilized with 10% formalin and was rinsed with sterile normal saline until the effluent tested negative for formaldehyde (CliniTest urine glucose test kits were used for this purpose). While this system was extremely crude, it was a vast improvement over embalming equipment, in that it allowed for sanitary and particulate free delivery of perfusate, with control over temperature and pressure. Unfortunately, the falling ball flow meter served to provide only the barest indication of the actual flow. In centrifugal pumps, unlike positive displacement pumps, such as roller pumps, there is essentially no correlation between the revolutions of the pump impeller per minute, and the flow produced. Even with the advent of electromagnetic and ultrasonic Doppler blood flow meters, the problem of measuring the flow of a perfusate with dynamically varying concentrations of cryoprotectant agent and electrolytes would remain unsolved for another 30 years.

Thus cryonics perfusions went from looking like this:

Figure 4: Cryoprotective perfusion as practiced in 1972.

Figure 4: Cryoprotective perfusion as practiced in 1972.

to looking like this:

Figure 5: Cryoprotective perfusion as practiced in 1976.

Figure 5: Cryoprotective perfusion as practiced in 1976.

My contribution to the Manrise machine was the bubble trap, which also accommodated a thermistor temperature measurement probe and allowed for measurement of perfusion pressure behind the cannulae. Since the machine was designed primarily for neuro-perfusion, and two large bore internal carotid arterial cannulae were used at low perfusate flow rates, this method of measuring pressure proved fairly accurate. Nevertheless, Fred and Linda laboriously produced a perfusate flow versus pressure drop (across the two carotid arterial cannulae) table that could be pressed into service should higher flow rates be required in perfusing whole body patients.

End of Part I

References

1) Ettinger, RCW, The Prospect of Immortality. Doubleday, New York, 1964: http://www.cryonics.org/book1.html. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

2) Horn, F. Perfusing and freezing a patient in Proceedings of the First Annual National Cryonics Conference, New York Academy of Sciences, 02 March, 1968, Cryonics Society of New York, 1968:40-45. http://cryoeuro.eu:8080/download/attachments/425990/Proc1stAnn+Cryo+ConfNYC1968.pdf. 2011-01-24.

3) Kent, S. Steven Jay Mandel frozen by CSNY. Cryonics Reports 3(9)1968:162-166. http://cryoeuro.eu:8080/download/attachments/425990/CryonicsReports3%289%291968.pdf. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

4) Editor, Will you embalm for the living? Casket & Sunnyside. http://cryoeuro.eu:8080/download/attachments/425990/WillYouEmbalm4LivingCasketSunnyside.pdf. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

5) Kent, S. Cryo-span Brochure, Cryo-Span Corporation, Sayville, LI, NY, 1969. http://cryoeuro.eu:8080/download/attachments/425990/CryoSpanBrochure.pdf. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

6) Federowicz, MD, et al. Perfusion and freezing of a 60-year-old woman. Manrise Technical Review. 3(1); 9-32:1973. http://www.lifepact.com/images/MTRV3N1.pdf. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

7) Chamberlain, FRC and Chamberlain, LLC. Instructions for the induction of solid state hypothermia in humans. Manrise Corporation, La Crescenta, CA, 1972: http://www.lifepact.com/mm/mrm001.htm. Retrieved 2011-01-24.