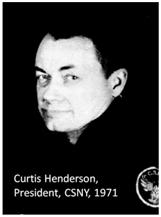

By Charles Platt and Mike Darwin

Cryo-Care Equipment Corporation

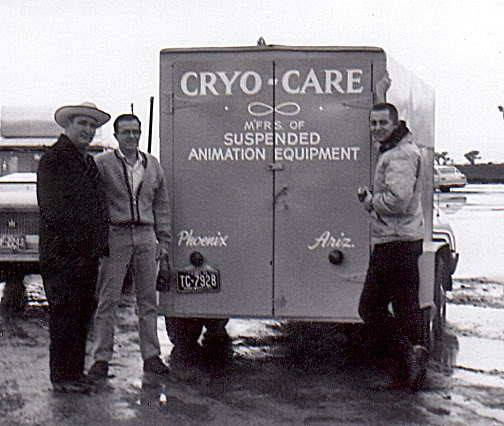

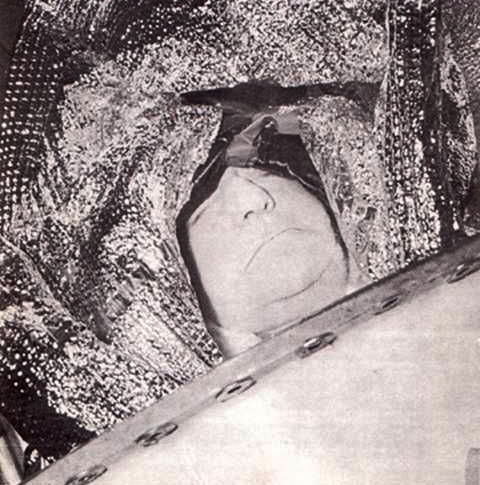

“At that time, the media were looking at cryonics from the point of view of sensationalism. They wanted to see someone get out of a coffin, you know? Saul and I went on across the country, and we found nothing genuine till we got to Ed Hope’s place in Phoenix, Arizona. That was another whole kettle of fish. He was actually building tanks. And he had two engineers working with him, he called his company Cryo-Care, and he had a woman in one of his tanks. Hope may be still alive, I haven’t heard from him in a long time. He’d married a wife from Germany, and he was doing well, importing wigs.[1] He had two wig shops in Phoenix. Ed Hope wore a wig. It used to blow off at bad times. Ed Hope was the kind of guy who’d be pinching waitresses, chatting to airline stewardesses.”

“At that time, the media were looking at cryonics from the point of view of sensationalism. They wanted to see someone get out of a coffin, you know? Saul and I went on across the country, and we found nothing genuine till we got to Ed Hope’s place in Phoenix, Arizona. That was another whole kettle of fish. He was actually building tanks. And he had two engineers working with him, he called his company Cryo-Care, and he had a woman in one of his tanks. Hope may be still alive, I haven’t heard from him in a long time. He’d married a wife from Germany, and he was doing well, importing wigs.[1] He had two wig shops in Phoenix. Ed Hope wore a wig. It used to blow off at bad times. Ed Hope was the kind of guy who’d be pinching waitresses, chatting to airline stewardesses.”

E. Francis Hope (at left).

E. Francis Hope (at left).

“We spent a couple of weeks there, actually working on these tanks, learning about high vacuum and helium-leak detectors, and all the rest of it. This was evolving away from the idea of having people do things for us. We could see that if we were going to do something, it was going to be a do-it-yourself back-alley kind of thing.”

From left to right: Ed Hope, Rick (last name not known) and Ted Kraver, the three principals of Cryo-Care Equipment Corporation. Ted and Rick were former NASA engineers who departed NASA as the US manned space program wound down.

From left to right: Ed Hope, Rick (last name not known) and Ted Kraver, the three principals of Cryo-Care Equipment Corporation. Ted and Rick were former NASA engineers who departed NASA as the US manned space program wound down.

Ed Hope and two Cryo-Care employees wrap the inner can of a ‘Cryocapsule’ with alternating layers of aluminized Mylar and fiberglass spacer. Photo by Curtis Henderson, 1966.

Ed Hope and two Cryo-Care employees wrap the inner can of a ‘Cryocapsule’ with alternating layers of aluminized Mylar and fiberglass spacer. Photo by Curtis Henderson, 1966.

Cryo-Care CC-101 Cryocapsule with bolt-on inner header. A lead gasket was to be used to affect a seal between the header and the body of the inner can, thus isolating the vacuum space from the liquid nitrogen. This system proved unworkable and was abandoned.

Cryo-Care CC-101 Cryocapsule with bolt-on inner header. A lead gasket was to be used to affect a seal between the header and the body of the inner can, thus isolating the vacuum space from the liquid nitrogen. This system proved unworkable and was abandoned.

Photograph of first woman cryopreserved by Cryo-Care in 1966 upon removal from storage and conventional inerment. Photo by Ted Kraver.

Photograph of first woman cryopreserved by Cryo-Care in 1966 upon removal from storage and conventional inerment. Photo by Ted Kraver.

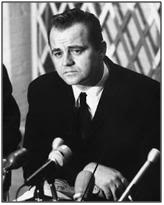

Bob Nelson, aka Frank Bucelli

Robert F. Nelson (at right)

After we left Phoenix we went to California and met Nelson, who had started the group there. All these people were very unhappy with Ev Cooper, and for the same reasons we had been; his vagueness, his need to control every aspect of operation, and so on. So, we met Nelson. They say he was charismatic, but I didn’t think so. He said he had this electronics business – he’s telling me these things and I’m sitting there with his credit-check and knowing all the while his real name wasn’t Robert Nelson it was Frank Bucelli.[2] The fact was his wife was supporting him, working as a teller in a bank. He carried on about all his technical knowledge, and so long as he was talking to someone who knew nothing about it, he could get away with it. But already I was building up a body of knowledge and I was beginning to be able to tell what was genuine and what was bullshit. Essentially, I taught myself basic cryogenics, hands-on. And boy, it got to be real hands-on.”

“I can’t explain why people believed Nelson. He was full of energy, willing to grab the flag and charge the enemy—the opposite of Ettinger. Proceed: regardless of the odds, regardless of the consequences, regardless of anything. He was the leader of this group, very enthusiastic, overjoyed that we gave them permission to use our stationery. We were the big people from New York in our big Buick; we did a very good job of putting on an image, of course. Even now we still have the same kind of situation, cryonics is a stage show, and we don’t really have very much substance. Anyway, we projected a great image, moving and doing things. We were the only ones putting out a newsletter, printed on one of those old copying machines, with the wood alcohol fluid that stunk to high heaven–we were the big shots.”

“We headed back to New York through Las Vegas. In those days you could get a steak dinner for about two dollars and a half; as long as there were fools to gamble, you could live like a king. Anyway, we’d called this guy named Tom Tierney, and there were all kinds of weird clicks on the line. [3] We were sitting in a restaurant, and here come the police. We were marched off to jail. They said they knew we’d got the money, where was the money? And Saul says, ‘No, no, officer, we just freeze bodies.’ Saul walked them back to the trunk of the Buick which was stuffed full of cryonics literature. That backed them off a bit. Anyway, we went into the clink. After a long night, it seems that Tierney was in the counterfeiting and gun-running business. And not only that, a Buick just like mine had been picked up here on Long Island in Patchogue, two days before, with a million dollars in fake $20 bills in the trunk. Well, fortunately when Tierney sent us his contribution, he sent us a check.”

“We headed back to New York through Las Vegas. In those days you could get a steak dinner for about two dollars and a half; as long as there were fools to gamble, you could live like a king. Anyway, we’d called this guy named Tom Tierney, and there were all kinds of weird clicks on the line. [3] We were sitting in a restaurant, and here come the police. We were marched off to jail. They said they knew we’d got the money, where was the money? And Saul says, ‘No, no, officer, we just freeze bodies.’ Saul walked them back to the trunk of the Buick which was stuffed full of cryonics literature. That backed them off a bit. Anyway, we went into the clink. After a long night, it seems that Tierney was in the counterfeiting and gun-running business. And not only that, a Buick just like mine had been picked up here on Long Island in Patchogue, two days before, with a million dollars in fake $20 bills in the trunk. Well, fortunately when Tierney sent us his contribution, he sent us a check.”

“We came back through Detroit, where Ettinger was going to have his big annual meeting. And we were like Caesar coming back from Egypt, you know. It really was just like that. Everywhere we’d gone; our visits had turned the groups into cryonics societies. So we got to this big dinner and Ettinger announced he was starting the Cryonics Society of Michigan. And that was the end of Ev Cooper’s Washington operation.”

The original Chamber of Commerce brochure from which all cryonics Phoenixes are descended.

“When we were in Phoenix, I got a thing from the chamber of commerce, I got the emblem redrawn and Paul Segall had a patch made up. There was an explosion of activity, it looked wonderful, we’d ordered one of Hope’s tanks, and nothing could stop us now. We came back to 306 Washington Avenue bathed in glory. Now we were going to really do it. It was the dawning of a new age, and so on and so forth.

But, of course, it wasn’t.”

Growing Up Red

“My father was a professor of economics at Columbia. In the 1920s, every New York intellectual was a communist, and of course he was bitten by the same bug; all the economics professors were tired of capitalism. It was the Depression and the economics professors and academics were holding dinner waiting for the revolution. Everything that was happening was happening in Russia, blah, blah, blah. He wanted to go to Russia. My grandmother, who had a lot of money, didn’t approve of taking a kid to Russia, where people were starving and the revolution was going to be crushed by the good fascists.[4] So you see I was inundated with two different political philosophies from a very early age.”

The “Little Red School House for Little Reds” is still in operation in New York City today in the building. This is a contemporary photo of the structure. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“My father later started one of the unions that were to become part of the CIO. The civil rights movement was started by communists; that’s a fact.”

“We moved around constantly. I traveled around a lot and I was in a communist school, the Little Red School House.[5] We used to play at war all the time, the big kids were the Russians, and little kids were the Americans. The Americans always had to surrender at the end. Eventually my grandmother put me in a private school; South Kent School in South Kent, CT. Kent was a rigorous private boy’s school that provided a classical education. You studied from 6 AM to 9 PM. There were long assignments; Shakespeare, Milton, the Canterbury Tales – a strict classical education.”

“I had two younger brothers. Eventually there were terrible fights in the family. My old man stayed a Stalinist, I guess, till the day he died. So anyway, my parents were fighting all the time. My mother died when I was about eleven.[6] I wasn’t really close to either of them. My grandmother had hired this French woman during the First World War who had stayed with her all her life, who was always with the family, and really I was closer to her. My grandmother had trust money that her father had never got a chance to spend – my parents, these were the kind of communists who sit in a nine-room apartment on Central Park West, with servants waiting on them, while they’re talking about helping the working class. The arrogant superiority of them – they knew capitalism was doomed, and the intellectual community mostly agreed with them. I was nine or ten years old, at summer camps, where they’d have the League of Women against War and Fascism. But to me, playing soldier was heaven. I was into Beau Geste. The Foreign Legion was considered the most fascist thing in the world, but to me, it was the place to go.”

“Even though you may not believe in all of the Marxist trappings, when you’re there in the morning, and you sing the Internationale[7] – it’s a feeling, I guess, like religion. You’re in a group, and you’re constantly told you’re the elite. You’re going to conquer the world. And it affects you. And you could see the connection. Most of the Nazis came out of the old Rosa Luxemburg converts for the communists.[8] It’s hard to picture it now, but everybody was looking for answers in one of these movements. Lindbergh’s wife wrote a book called The Wave of the Future, in which the Nazis were the future. Meanwhile, the Left was saying, ‘I’ve seen the future and it works.’ I remember my early teenage years when the trials started in Russia, I’d be lying half asleep and I’d hear the adults arguing over this. My parents were Stalinists, so they could always find an excuse why this was going on. The people on trial were traitors, Trotskyites, and so forth. And meanwhile the Depression was going, there were demonstrations in the street, all that kind of thing.”

“I spent a summer with my grandmother in a cottage that she rented in Newport, Rhode Island. That was a happy time for me. I met a girl named Judy Cowey; well, I couldn’t breathe when she was in the room. At that time Betty Grable was the ideal of female beauty, but Judy was much prettier. It was a good summer. My uncles were extreme right-wing; they talked about Roosevelt as ‘That Man in the White House.’”

“When you’re young, you don’t think of death. And certainly in those circumstances, I did not consider the possibility of my death. When there was the Hitler-Stalin pact, the communists and the fascists uniting, well, we felt the old world didn’t have a chance. Everything was going to change for the better with coming of the new world order.”

“There were constant philosophical arguments in the family. There were all kinds of people going in and out of the apartment.”

“I went into the Army Air Corps right from boarding school, when I wasn’t really seeing my parents anymore. I never graduated high school. If you joined the air cadets, they gave you your high school diploma; which, of course, was wonderful. I had a big old 1932 Harley, and I made the Air Cadets, I had a big shoulder patch with a propeller on it.”

“I went into the Army Air Corps right from boarding school, when I wasn’t really seeing my parents anymore. I never graduated high school. If you joined the air cadets, they gave you your high school diploma; which, of course, was wonderful. I had a big old 1932 Harley, and I made the Air Cadets, I had a big shoulder patch with a propeller on it.”

“But the Germans and the Japs quit before I ever had a chance to engage in combat. The frustration! VE Day and VJ Day, everyone’s cheering and throwing their hats up in the air, and the air cadets are looking like there’s a funeral going on. In the end they made us teletype operators to replace WACS.”

“I was an avid science-fiction reader. And I had a lot of self-confidence. The Air Corps helped there; they gave me all these tests, and the class was whittled down till the last four or five made it into the cadets, me among them. We were treated like officers, special passes to leave the base. I had everything going for me, if I’d stayed in, maybe I would have been an astronaut, I don’t know. But I decided to get out; I had the big motorcycle and $70 pay.[9] It felt like a million dollars. And I had a vague indefinable feeling that maybe I was going to get out of it; I wasn’t going to die. Death was something that was never going to happen to me.”

“After the war, everyone was going to school on the G.I. Bill. I got into a place called the Pennsylvania Military College, studying electrical engineering. Then I switched to political science. But I always had a talent for engineering, I worked on my own cars, I had part-time jobs in garages. At school, that was a great life. They paid me to go to school, so I had enough money; I had a motorcycle, a new convertible.”

“Then there was the Korean War. But in that war we were fighting the communists, so there were no commissions for the likes of me.”

“The more I saw of the working class, the more I realized that they didn’t consider themselves ‘the working class.’ They considered themselves individuals, in most cases.”

“I got a job in a tank factory, welding Army tanks. I was one of the first stainless-steel welders in the country, welding big thick armor plate. Why I didn’t die there I’ll never know. People were getting burned up and electrocuted all the time. I never thought twice about it. I was breathing fumes – that was before pollution controls and all this OSHA workers safety stuff.”

“During the McCarthy years, that was an unreal feeling. Of course, those people were all communists. I knew them from my childhood. I’d met them. Why they couldn’t just stand up and say, ‘of course I’m a communist, so what?’ But they lied about it, they betrayed each other. You know, 99 percent of people have this loyalty toward whatever you want to call it: the system, the country. And they have a guilt feeling. But I never had that. I always thought of myself as an individual first, and I think you’ll find that all through cryonics.”

“Then I went to law school. Did I seriously want to be a lawyer? I said so, then, but I don’t know. Again, I was leading a very good life. There was no hardship. I always could get part-time jobs, and most of them were enjoyable. I even loved the tank factory – the sound, the banging, and the crashing. It was like being in hell! I loved it.”

“I graduated law school, and I got a job with the Hardware Mutuals Insurance Company. But at some point, I think you say, ‘What’s this got to do with me?’ Then I married a girl I met in law school. I never took my grandmother’s advice, but of course, she knew what she was talking about. I should have married the judge’s daughter, or at least been nice to the judge’s daughter.”

“I did pretty well investigating cases. In those days, you know, insurance companies investigated claims, they fought them. Now they just pay them and raise the premiums.”

Miscellany

Did cryonics ruin your life?

“It certainly did in a conventional sense. Absolutely. I didn’t do the things I was supposed to do. Cryonics was an excuse that allowed me not to do the conventional things that would have led to success as a lawyer, or anything else. Cryonics was a cause, a fascination.”

“After we got back from our trip across the country, it was only a couple of weeks, it seems, before Nelson, in California, got involved in freezing Bedford. From then on, for the next few years, history revolved around the struggle between cryonics in New York and cryonics in California.”

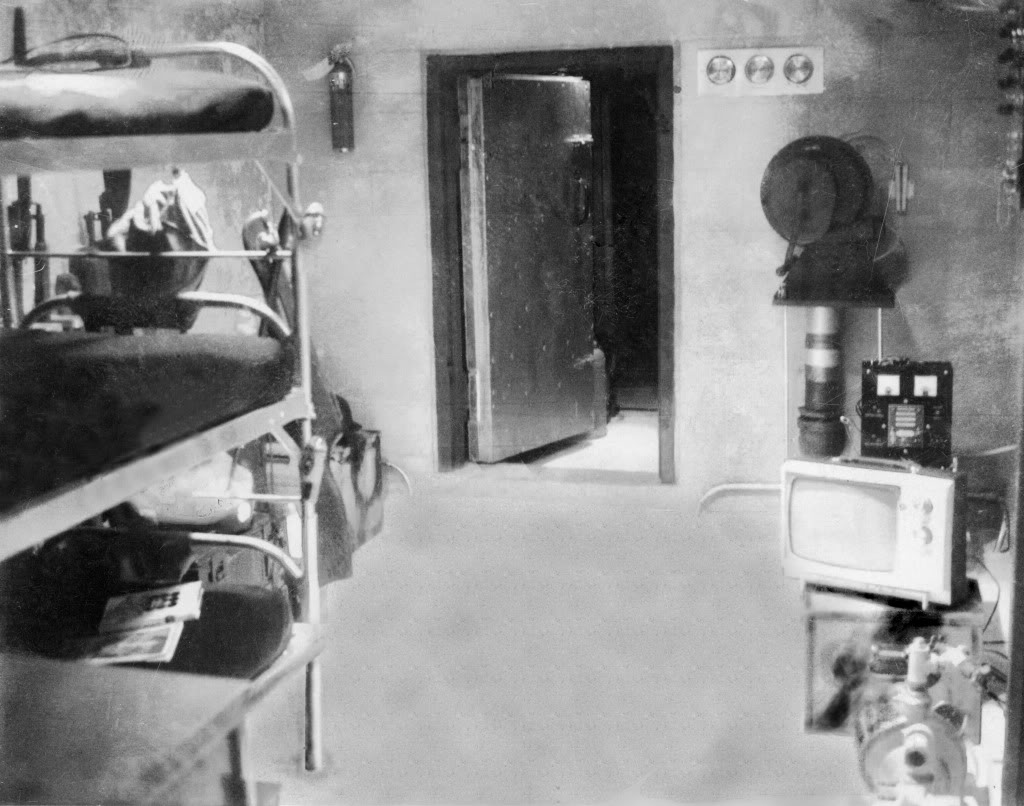

Pillbox surface terminator of the Henderson Family nuclear blast shelter at 9 Holmes Court, Sayville, Long Island, New York

Pillbox surface terminator of the Henderson Family nuclear blast shelter at 9 Holmes Court, Sayville, Long Island, New York

Leaving the house:

“I’ve been cleaning this up [the bomb shelter] because now I think maybe we will have a nuclear war, the way things are going with the Russian republics. This thing was a labor of love, here.”

In the basement: pegboard over a work bench, a welding mask and tools. A knife switch with bare terminals controls the lights in the shelter.

“This door was supposed to work hydraulically, but I stripped the car batteries out because I’m using them for cryonics, now.”

“Watch your head down here.”

Interior of the underground blast shelter constructed by Curtis Henderson at the height of the Cold War.

A stack of old ammunition boxes rests in an alcove off the main tunnel. The air is amazingly cold. There’s an alcove for a chemical toilet, and a hand-cranked air pump. The bunker is concrete four feet thick, and four feet of earth on top of that. We climb a rusty steel ladder up to the observation bunker. It took him two years to build the whole thing:

“A labor of love.”

“The composition of the concrete was one part Portland cement, one part of sand and one part of chipped granite. That was what the Japanese used for their fortifications on an island where they really gave the Marines a bad time.”

After leaving the bomb shelter we enter the garage.

“That Buick needs a new carburetor. I have to resurrect it again. Everything here, the kitchen or whatever, it’s always being resurrected.”

There are two large Japanese motorcycles in the garage. One is Curtis’s; the other belongs to his son.

“Mine normally lives in the living room.”

We climb wooden stairs to an attic above the garage. There are big old rusty file cabinets full of ancient cryonics literature spotted with age and cobwebs.

Curtis Henderson (left) and Mike Darwin in the summer of 1972 at the Cryo-Span facility on Long Island, New York.

“Mike Darwin once said he came here and discovered that cryonics was run by two guys, one of them an alcoholic, one of them a beach comber. I was the alcoholic, Saul used to go to Fire Island and lie on the beach and at the end of the month he came up with a newsletter.”

At the Modern Diner:

“My son Robbie, he put up the flag. Robbie, from the time he was an infant, spent time on my big wooden boat in the bay. I guess it’s only natural – there used to be oysters in the bay, and clams. This used to be the big slaving center here; the South Beach was used as a great pen for slaves. They’d be sent from there, north or south. Of course, now they call the South Beach Fire Island. Actually Fire Island is down at the other end. But if you go to the library here you can see the records of the slave transactions.”

“Long Island was settled from the east, not the west, in the early days. People came by boat. Everything was by boat. When I first came here, a lot of the clam boats were still the old Dutch hulls, 200 years old.”

Henderson looks reflective, apparently thinking of those days before cryonics.

“That little airplane, I loved it. I could do anything with it. I could land in thirty feet with that plane.”

“By now my divorce had proceeded to its final stages. I have three sons. Don’t have children, they worry you to death. My first wife went off to Florida, but I ended up with custody of the two kids, which was a real problem. She was complaining they were being dragged all over the place, and she had pictures of Robbie and Jamie sleeping in the tank. But the judge didn’t buy it. You know, Robbie was named after Robert Ettinger.”

The First Cryonics Conference

“In 1966 we had this discussion group, and the newsletter and we were not really moving forward at the pace we felt we had to. We had a tank that John Flynn bought, claimed that he was going to do all this research, freeze a chimpanzee… But he didn’t. He eventually stored it in a cave in the Bronx where a man had a collection of nickel violins – violins where you put a nickel in, and it would play. He wasn’t paying for the storage, so we had to bring the tank back here. He still says it’s his, but I say there’s $10,000 storage on it.”

“There was no serious way of putting liquid nitrogen in that tank. Hope tried to create a vacuum, but the next tank that Hope made had a welded inner chamber, made of high-grade stainless steel. That tank in the yard is made out of an old oil tank. The new tank was a better design. We bought the second tank for $3,000. Saul and I paid for it out of our pockets. We had written to every funeral parlor on Long Island, and got literally no response, except from Fred Horn at St. James funeral parlor. We went over to see him, and the only reason he was interested was he had broken his leg skiing and he had nothing better to do.”

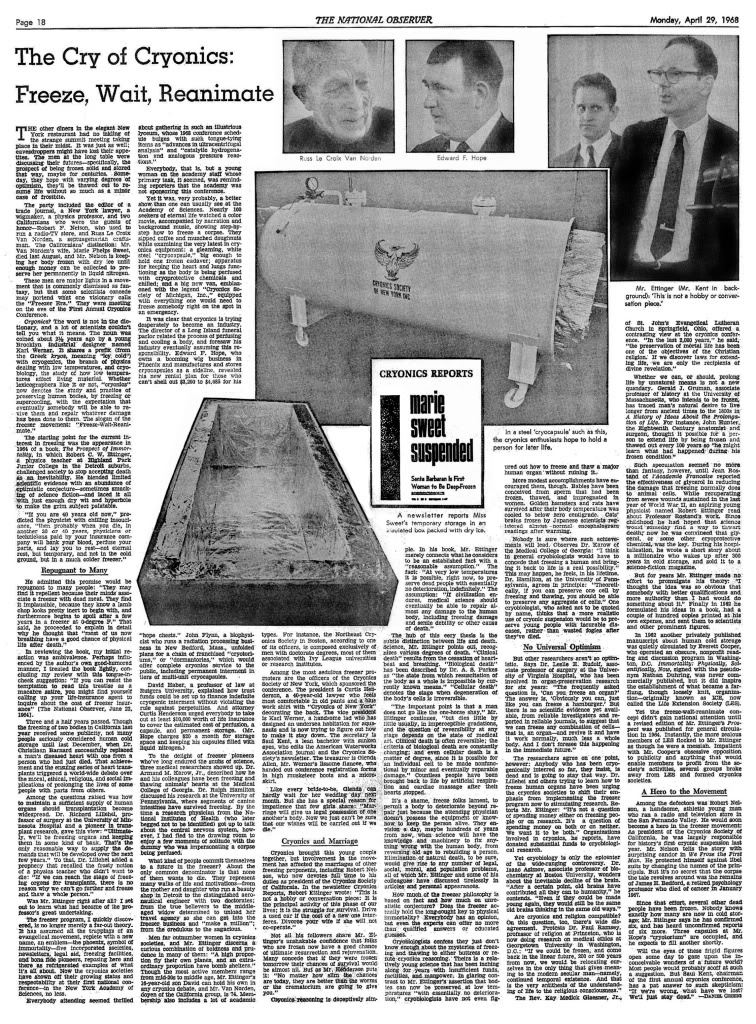

National Observer covering the first Cryonics Conference held at the New York Academy of Sciences in March of 1968. An easier to read PDF version of this article is available here: http://cryoeuro.eu:8080/download/attachments/425990/CryofCryonics_Natnl_Observer_March1966C.pdf

“Fred became involved and we began to buy equipment and chemicals. With some difficulty I got hold of 10 gallons of DMSO from the Crown-Zellerbach paper company. We were getting set up. So, we decided to put on the first cryonics conference.[10] The way this got started was, we met Robert Duncan Enzmann, who lived on Adams Street in Lexington. He worked for Raytheon. I remember during the Vietnam War, he was working on these secret weapons systems, and he talked about hitting a rocket with another rocket. Seemed pretty far-fetched then, but he knew what he was talking about. He had three PhDs. He had connections with the New York Academy of Sciences, next to the old Knickerbockers Club. He said sure, have the conference there. So I went down in my clean collar and brand-new suit, and paid the $100 for the Cryonics Society to have its conference there, no one knowing what the Cryonics Society was.”

The complete proceedings of the First Annual Cryonics Conference are available here: http://cryoeuro.eu:8080/download/attachments/425990/Proc1stAnn+Cryo+ConfNYC1968.pdf

The complete proceedings of the First Annual Cryonics Conference are available here: http://cryoeuro.eu:8080/download/attachments/425990/Proc1stAnn+Cryo+ConfNYC1968.pdf

“And Saul did the work, setting it up, writing letters, visiting people who claimed they were doing anti-aging research, all sorts of things. Then one day Enzmann said he had a sister who’s a doctor. She had this apartment right by the children’s zoo. And here’s another thing about writing a history of cryonics, it’s full of things that I really don’t want – well, I’m not running for President, but maybe I might. But she turned out to be a very attractive young girl. So I started running around with her. Her apartment was just a few blocks from the Academy of Sciences, so I ended up staying there while we were setting it up.”

“The conference was a fantastic success. We had the two tanks, all painted up with the name on the side. I’d sold my plane, because its motor was shot. The compression was so low; you had to use three batteries in series to get it started, to spin the motor fast enough. See, now it was getting away from being a discussion group, a fun thing, to something that was consuming money.”

Dr. M. Coleman Harris, M.D., circa 1968-69. Dr. Harris, a highly respected physician and an Editor of the medical journal Annals Of Allergy at the time, was one of the founders of the Bay Area Cryonics Society.

“Meanwhile there were these terrible fights in California. Nelson said, “What do you mean you told the people in San Francisco they could start a cryonics society?” He said, ‘I’m the California Cryonics Society.’ At first I wouldn’t take him seriously. I said, ‘the man is a medical doctor, he can incorporate anything he wants, and he doesn’t need our permission.’[11] But Nelson said, ‘California belongs to me.’ It was ridiculous, but he didn’t see it as being ridiculous. You see, our whole policy was to set up a cryonics society in every little town. The only way you’re going to get this to work is to be spread really thin so you get those two or three people in each community, who this appeals to. So we started the idea of coordinators, to get lots of little groups. But Nelson was seeing it more as an empire.”

“Nelson saw the world as being structured from the top down; you’ve got a strong leader, and he makes everyone do things. But it doesn’t work that way. You can’t push people into their places. People do what they feel comfortable doing. You have to wait for people with the talent and the inclination to do what they want to do. You can’t go out and say, I want volunteers! You, you, and you! You know what you get? You get someone saying, ‘I don’t want to carry the flamethrower.’ That’s what you get.”

“The day before the conference, we’d done everything. We’d sent out press releases, and I showed up with the truck with the two tanks on it and a dry-ice box. Then the girl at the Academy office asks me, what’s all that? I couldn’t resist a joke, I told her, ‘I don’t get out of these boxes till the sun goes down.’ Then Admiral Johnson suddenly realized what was happening, and what we were really all about. Now he’s reading in the paper that the body freezers are taking over his institution. But it was too late to stop it. So it was one of our great coups. And it was a great conference. I don’t think it’s been duplicated since. So once again, it looked as if everything was going to go; this was going to be it.”

End of Part 3

Footnotes:

[1] Hope’s wife was very unpleasant and loathed cryonics. She was a rotund babushka of a woman. MD

[2] Henderson had also had a Pinkerton report prepared on Nelson which disclosed, among things, a criminal past in Boston, Massachusetts.

[3] Henderson and Kent went to visit Tierney because he had given $1,000 to LES. MD

[4] It was Henderson’ maternal grandmother who put a stop to it; the Henderson’s were not self-supporting and his Grandmother threatened to cut off the financial support. MD

[5] The Little Red School House (sometimes simply referred to as LREI or ‘Little Red’) and infamously referred to as the “Little Red School House for Little Reds” was founded by Elisabeth Irwin in 1921 in New York, NY. It is widely regarded as the city’s first progressive school. Founded as a joint public-private educational experiment, the school tested principles of progressive education advocated since the turn of the century by John Dewey. Little Red postulated that the lessons of progressive education could be applied successfully in the crowded, ethnically diverse, public schools of the nation’s largest city. Nevertheless, in 1932, the school turned to private funding, with tuition ranging, today, from $24,240 to $27,200. MD

[6] In 2007, Henderson told me that his mother committed suicide by drinking a bottle of witch hazel. She had been a long-time alcoholic and suffered from bouts of intense depression. MD

[7] The Internationale (L’Internationale in French) is a famous socialist, anarchist, communist, and social-democratic anthem and one of the most widely recognized songs in the world. The Internationale became the anthem of international socialism. Its original French refrain is C’est la lutte finale/ Groupons-nous et demain/ L’Internationale/ Sera le genre humain. (Freely translated: “This is the final struggle/ Let us join together and tomorrow/ The Internationale/ Will be the human race.”). MD

[8] Rosa Luxemburg (Polish: Róża Luksemburg,) (5 March 1870/71 – 15 January 1919), was a Jewish Polish-born German Marxist theorist, socialist philosopher, and revolutionary for the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania, the German SPD, the Independent Social Democratic Party and the Communist Party of Germany .In 1914 after the SPD’s supporting German participation in World War I, she co-founded, with Karl Liebknecht, the revolutionary Spartakusbund (Spartacist League), that on 1 January 1919 became the Communist Party of Germany. In November 1918, during the German Revolution she founded the ‘The Red Flag,’ the central organ of the left wing revolutionaries. She regarded the Spartacist uprising of January 1919 in Berlin as a mistake, but supported it after it had begun. When the revolt was crushed by the Freikorps (monarchist army remnants and right-wing freelance militias collectively), Luxemburg, Liebknecht and hundreds of left-wing revolutionaries were captured, tortured, and killed. Since their deaths, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht achieved great symbolic status amongst democratic socialists and Marxists. See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosa_Luxemburg. MD

[9] Approximately $875 in 2000 dollars ($70 ÷ 0.080 =$875 ): Robert C. Sahr, Political Science Department, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR: ttp://www.wvec.k12.in.us/EastTipp/8/invent/handouts/cv2000.pdf MD

[10] The first annual Cryonics Conference was held on 01-01-1966 at the New York Academy of Sciences. MD

[11] The Medical Doctor was M. Coleman Harris, M.D., a blue-blooded, patrician of San Francisco and editor of the prestigious journal ‘Annals of Allergy.’ Harris was an allergist – wealthy, conservative, and impressively intellectual. MD