By Mike Darwin

Determining and Documenting Cardiopulmonary Arrest

In situations where irreversibility has been established by a properly executed medical directive not to pursue cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) or defibrillation (especially in cases where the patient is of advanced age, in poor health, or is terminally), it still necessary to objectively determine and document cardiopulmonary arrest.

In most countries, including the U.S., Canada, and the U.K., there are currently neither statutory rules, nor standardized criteria for the certification of death following irreversible cessation of cardiorespiratory function (or for that matter following so-called “brain death,” or more properly, pronouncement of death in the presence of mechanically assisted cardiopulmonary function using neurological criteria)†.[1],[2],[3],[4] As a result, current practice varies from certifying death as soon as an attempt at cardiopulmonary resuscitation is abandoned, to waiting 10 minutes, or longer, after the onset of respiratory and cardiac arrest (apnea and aystole).[5],[6],[7] Criteria used to determine apnea and aystole may vary widely from institution to institution within the same city, and additional criteria may also be required, such as the presence of fixed, unresponsive pupils (either dilated or in mid-position), absence of a corneal reflex (a response when the clear “window” of tissue covering the eye is touched with a finger tip, a gauze pad, or a cotton-tipped swab), and/or absence of response to painful stimuli such as knuckling (rubbing) the sternum or moderately depressing the globe of one eye.[1],[8] In some institutions, asystole may be determined only by careful auscultation of the chest (listening for a heartbeat with a stethoscope), while in others, the absence of a carotid pulse is considered adequate. Acceptable times for absence of heartbeat and breathing vary from immediately following failed cardiopulmonary resuscitation, to periods as short as 3 minutes or as long as ten minutes.[9],[10],[4],[11],[12]

The typical criteria taught to physicians for pronouncing death are an examination that includes, at a minimum, the general appearance of the body, no response to verbal or tactile stimulation, no pupillary light reflex (pupils fixed and dilated or fixed in mid-position), absence of breath sounds, and absence of heart sounds.[13]

MAYOR (singing): As mayor of the Munchkin City

MAYOR (singing): As mayor of the Munchkin City

In the county of the Land of Oz,

I welcome you most regally.

BARRISTER (singing): But we’ve got to verify it legally.

To see…If she…

Is morally, ethic’ly

CITY FATHER NO. 1:Spiritually, physically

CITY FATHER NO. 2: Positively, absolutely

ALL THE CITY FATHERS: Undeniably and reliably DEAD!

– From the film The Wizard of Oz, 1939.

In the U.S. and most of Europe, the use of painful stimuli such as deep the sternal rub or nipple twisting are now considered inappropriate, although this practice continues in some institutions and by some physicians, and still widely used in Eastern Europe and the developing world. In the scant published literature on the topic, there are some physicians who advocate additional testing for a corneal reflex (blinking when the cornea is touched with a gauze pad or cotton swab), but this is considered duplicative of pupillary reaction to light by other authors, since both reflexes require some intact brainstem function in order to occur.

Admonitions are also universally given to be aware that drug intoxication has the ability to produce complete cessation of brain function, including the electroencephalogram (EEG) (and can be completely reversible) and that total paralysis can also closely simulate death; as can certain critical illnesses such as end-stage liver disease (stage IV hepatic coma) that can make a live patient appear dead. Similarly, physicians are cautioned that profound shock (from blood loss or infection) and profound hypothermia (body temperatures below 32.2ºC or 90ºF) often require far more careful clinical examination because of reduced brain and body metabolism. Infants and children under the age of 5 are surprisingly resilient and have been known to recover completely after prolonged periods of apparent clinical death (cardiorespiratory arrest).

The problem with all these methods is that they are subjective and do not lend themselves to objective documentation. Within the fraternities of medicine and law enforcement, such lack of objective documentation is taken for granted, and this lack of rigor (surprisingly) results in fewer than a dozen cases each year (coming to public attention in the U.S. via the media) of patients awakening in the morgue, moving on the autopsy table as necropsy is begun, or otherwise being determined to have been mistakenly been pronounced dead. (A Google search using the key words “mistakenly declared dead” is all that is needed to find a roster of such cases occurring across the U.S. and around the world).

Thus, the question arises, “what criteria should be used by laypersons to determine “irreversible” cardiopulmonary arrest in the cryopatient?”

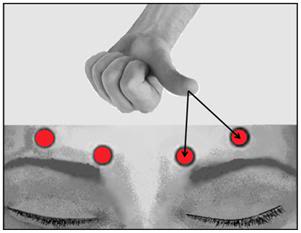

Figure 1: Procedure for application of supraorbital pressure.

Figure 1: Procedure for application of supraorbital pressure.

Field Determination of Irreversible Cardiopulmonary Arrest (ICPA)

First, remember, looks can be deceiving. A visit to most extended care facilities (ECFs) or hospitals would probably reveal a patient or two whose status appeared questionable on initial observation. Second, follow the guidelines below to both determine the patient’s cardiopulmonary status, and to objectively document the signs used to determine “irreversible cardiopulmonary arrest” (ICPA). Above all, remember it that it is ICPA you will be determining, not death.

Field pronouncement of ICPA should follow the following protocol:

1) Whenever possible (and this should be an integral part of the Last Aid Kit (LAK)) a video recorder should be used to document the protocol, and once turned on it should be left on without interruption until the examination is completed. This secures a continuous record and establishes a documented time line. Absent this, remember that later generation mobile phones and virtually all smart phones have embedded cameras, and often video recording capabilities.

2) Use the mechanical or electronic stopwatch in the kit to formally measure the requisite time intervals for the various determinations. (Mechanical stopwatches have the advantage of not needing batteries.)

3) The patient must demonstrate lack of response to verbal or tactile stimulation. This should include calling the patient by name, and application of supraorbital pressure, as shown in Figure 1, above.

4) There must the simultaneous and irreversible onset/presence of apnea and unconsciousness in the absence of the circulation. Apnea should be demonstrated by using a clean, highly polished mirror as shown in Figure 2 below, to document that there is no fogging due to respiration for a period of 3 minutes. Apnea should be confirmed by auscultating the chest as shown in Figure 4, below, following determination of aystole (cardiac arrest) by auscultation, or use of the CapNoMask as shown in Figure 7, below.

5) Absence of circulation, as documented by absence of a carotid pulse on palpation, and the absence of heart sounds on auscultation using a quality stethoscope, as shown in Figure 3, below.

Figure 2: Portable mirror with case for determining that respirations have ceased.

Figure 2: Portable mirror with case for determining that respirations have ceased.

6) One of the following is fulfilled:

− The patient meets the criteria for not attempting cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

− Attempts at CPR have failed, as documented in writing by an authorized person (attending physician or EMS personnel).

− Treatment has been withdrawn because it has been determined to be of no further benefit to the patient and not in his/her best interest to continue, and/or in respect of the patient’s wishes, as documented in writing by the patient, or per the patient’s medical record, or per written instruction from the patient’s primary care physician, or other authorized health care provider.

Figure 3: High quality Rappaport-Sprague stethoscopes such as the one shown above are available at many home health care retail outlets for under $30.00 US.

Figure 3: High quality Rappaport-Sprague stethoscopes such as the one shown above are available at many home health care retail outlets for under $30.00 US.

7) The patient should be observed for a full 5 minutesto confirm that irreversible cardiorespiratory arrest has occurred. The absence of mechanical cardiac function can be confirmed and documented with increased accuracy using any one (or a combination of) the following, if available:

− Recorded absence of heart (and breath) sounds using the phonocardiomonitor described in Figure 5 below.

− Absent blood pressure readings (including plethysographically acquired pulse) on the automatic blood pressure and pulse monitor, as shown Figure 6, below.

− No exhaled carbon dioxide indication on the Capnomask shown in Figure 7, below.

Figure 4: The chest should be auscultated in multiple areas to ensure that heartbeat has ceased. The locations shown in the diagram above are good locations to listen. Regardless of what type of stethoscope head is used, always auscultate with the flat, diaphragm side of the head, as shown at far right, above. Be certain that this head is selected for listening by lightly tapping the diaphragm with a finger while the ear pieces are positioned in the ears.

Figure 4: The chest should be auscultated in multiple areas to ensure that heartbeat has ceased. The locations shown in the diagram above are good locations to listen. Regardless of what type of stethoscope head is used, always auscultate with the flat, diaphragm side of the head, as shown at far right, above. Be certain that this head is selected for listening by lightly tapping the diaphragm with a finger while the ear pieces are positioned in the ears.

8) Given, as per 6 above, that no further attempts are appropriate to restore the patient to present life, any spontaneous return of cardiac or respiratory activity during this period of observation should prompt a further five minute period of observation starting from the next point of cardiorespiratory arrest.

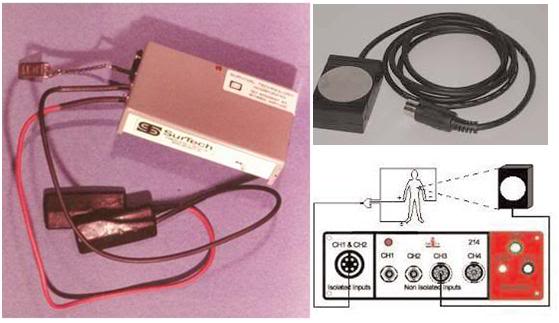

Figure 5: A phonocardiometer is a simple device consisting of a microphone (piezoelectric or conventional) and an amplifier and speaker. Alternatively, the microphone-amplifier assembly may be connected to a wireless transmitter to allow remote monitoring of the patient’s heart beat. The use of audible, rather than electrical monitoring of the heart eliminates the risk of pulse-less electrical activity (PEA) of the heart being confused with an actual “perfusing” heartbeat. PEA may continue for an hour or more after cardiorespiratory arrest has occurred. The unit pictured at left, above, was fabricated by Fred Chamberlain, III in 1975.A commercially available unit is the iWorx/CB Sciences (www.iworx.com) of Denver, NH, HSM-300, a simple device which converts the sound waves, created by the heart valves opening and closing, into voltages which can be recorded and displayed. A piezo-electric sensor, mounted on the side of the HSM-300 picks up the vibrations that are created by the heart sounds. The piezo crystals on the sensor convert the changes in pressure created by the vibrations into voltages. These voltages may be recorded along with the ECG of the subject to identify the specific heart sounds that occur during ventricular contraction and relaxation. The silver-colored sensing element of the HSM-300 is placed on the chest of the subject at one of the four prescribed auscultation areas. These areas are located over sections of the heart and large vessels containing the valves that create the heart sounds that can be heard with a stethoscope. The sensor of the HSM-300 picks the low frequency sound waves of the heart sounds and converts these waves into voltages that can be seen on a computer screen. The output of the HSM-300 is amplified so that the recorded waves are about 1V in amplitude

Figure 5: A phonocardiometer is a simple device consisting of a microphone (piezoelectric or conventional) and an amplifier and speaker. Alternatively, the microphone-amplifier assembly may be connected to a wireless transmitter to allow remote monitoring of the patient’s heart beat. The use of audible, rather than electrical monitoring of the heart eliminates the risk of pulse-less electrical activity (PEA) of the heart being confused with an actual “perfusing” heartbeat. PEA may continue for an hour or more after cardiorespiratory arrest has occurred. The unit pictured at left, above, was fabricated by Fred Chamberlain, III in 1975.A commercially available unit is the iWorx/CB Sciences (www.iworx.com) of Denver, NH, HSM-300, a simple device which converts the sound waves, created by the heart valves opening and closing, into voltages which can be recorded and displayed. A piezo-electric sensor, mounted on the side of the HSM-300 picks up the vibrations that are created by the heart sounds. The piezo crystals on the sensor convert the changes in pressure created by the vibrations into voltages. These voltages may be recorded along with the ECG of the subject to identify the specific heart sounds that occur during ventricular contraction and relaxation. The silver-colored sensing element of the HSM-300 is placed on the chest of the subject at one of the four prescribed auscultation areas. These areas are located over sections of the heart and large vessels containing the valves that create the heart sounds that can be heard with a stethoscope. The sensor of the HSM-300 picks the low frequency sound waves of the heart sounds and converts these waves into voltages that can be seen on a computer screen. The output of the HSM-300 is amplified so that the recorded waves are about 1V in amplitude

9) After 5 minutes of continued cardiorespiratory arrest, the absence of pupillary responses to light, of pupillary and corneal reflexes, and of any motor response to supra-orbital pressure, should be confirmed as shown in Figure 1.

10) The time of ICPA is recorded as the time at which these criteria are fulfilled, using the Documentation of Cardiorespiratory Arrest Form (DCAF) present as an addendum to this document.

11) Documentation should include the exam conducted, a description of the physical location where the patient was found or experienced cardiac arrest, the physical condition of the body, any significant medical history or trauma, the conditions that precluded resuscitative efforts, any contact with medical, police, or EMS personnel, and in whose custody the patient was left (i.e., EMS, C/ME, police or other peace officers, mortician, or cryonics organization representative).

Figure 6: Noninvasive plethysographically acquired automatic pulse and blood pressure monitors such as the ones shown above are another option for documenting the onset and continuing presence of cardiorespiratory arrest. State of the art machines such as the one shown on the left also incorporate oxygen saturation monitoring, but are quite costly (although they can often be leased). Another option is older used equipment, such as Critikon Dinamap 1846 SX noninvasive blood pressure and pulse monitoring system, shown at the right, above. These can be acquired refurbished from used medical equipment dealers for several hundred dollars.

Figure 6: Noninvasive plethysographically acquired automatic pulse and blood pressure monitors such as the ones shown above are another option for documenting the onset and continuing presence of cardiorespiratory arrest. State of the art machines such as the one shown on the left also incorporate oxygen saturation monitoring, but are quite costly (although they can often be leased). Another option is older used equipment, such as Critikon Dinamap 1846 SX noninvasive blood pressure and pulse monitoring system, shown at the right, above. These can be acquired refurbished from used medical equipment dealers for several hundred dollars.

12) Double check your findings with every available resource. If there is an ECG monitor attached to the patient at the time of cardiac arrest, make a recording (in two leads). Leave the leads on the body as confirmation of your assessment. If you have an automatic external defibrillator (AED) in the home (increasingly common), confirm it gives a “No Shock Advised” message when attached to the patient, and document this with videography.

Figure 7: The CapNOMask consists of and end-tidal CO2 detector that has been interfaced with a non-fenestrated mask that is easily affixed with an elastic strap. Any exhaled breaths from the patient will turn the indicator some shade of yellow or gray. Absence of any change in the indicator is definitive evidence of respiratory arrest.

Figure 7: The CapNOMask consists of and end-tidal CO2 detector that has been interfaced with a non-fenestrated mask that is easily affixed with an elastic strap. Any exhaled breaths from the patient will turn the indicator some shade of yellow or gray. Absence of any change in the indicator is definitive evidence of respiratory arrest.

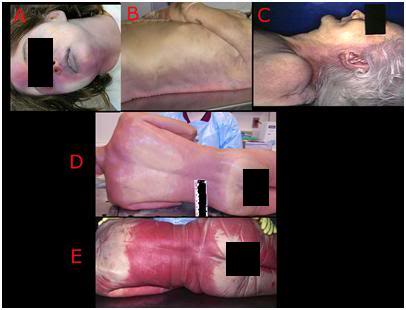

Figure 8: Varying Presentations of post cardiac arrest or postmortem lividity, also called postmortem hypostasis, occurs when blood settles or pools in the lowest (dependent) areas of the body under the influence of gravity. Wherever the patient is in contact with a surface under pressure, the small vessels are prevented from filling with blood (A, D, E) and remain pale and uncolored with blood. Lividity becomes “fixed,” in other words will not redistribute if the patient is moved, 6-12 hours after cardiac arrest (E). This is often accompanied by staining of the tissues with hemoglobin (cherry red, as seen in E, above) as a consequence of red cell breakdown (hemolysis).

Figure 8: Varying Presentations of post cardiac arrest or postmortem lividity, also called postmortem hypostasis, occurs when blood settles or pools in the lowest (dependent) areas of the body under the influence of gravity. Wherever the patient is in contact with a surface under pressure, the small vessels are prevented from filling with blood (A, D, E) and remain pale and uncolored with blood. Lividity becomes “fixed,” in other words will not redistribute if the patient is moved, 6-12 hours after cardiac arrest (E). This is often accompanied by staining of the tissues with hemoglobin (cherry red, as seen in E, above) as a consequence of red cell breakdown (hemolysis).

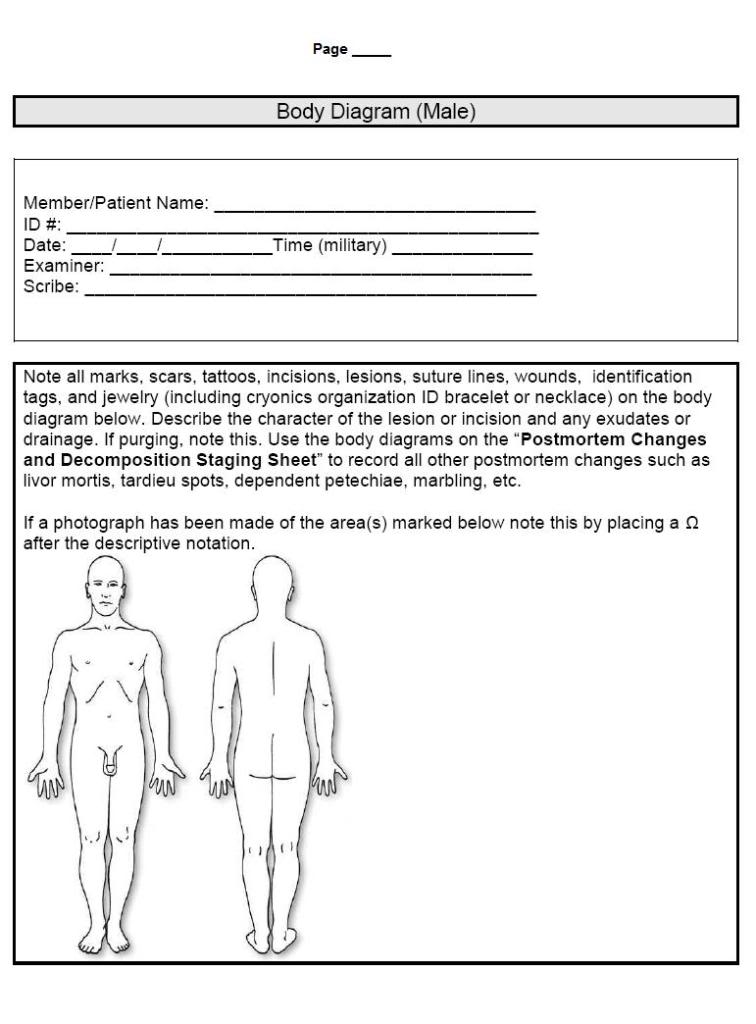

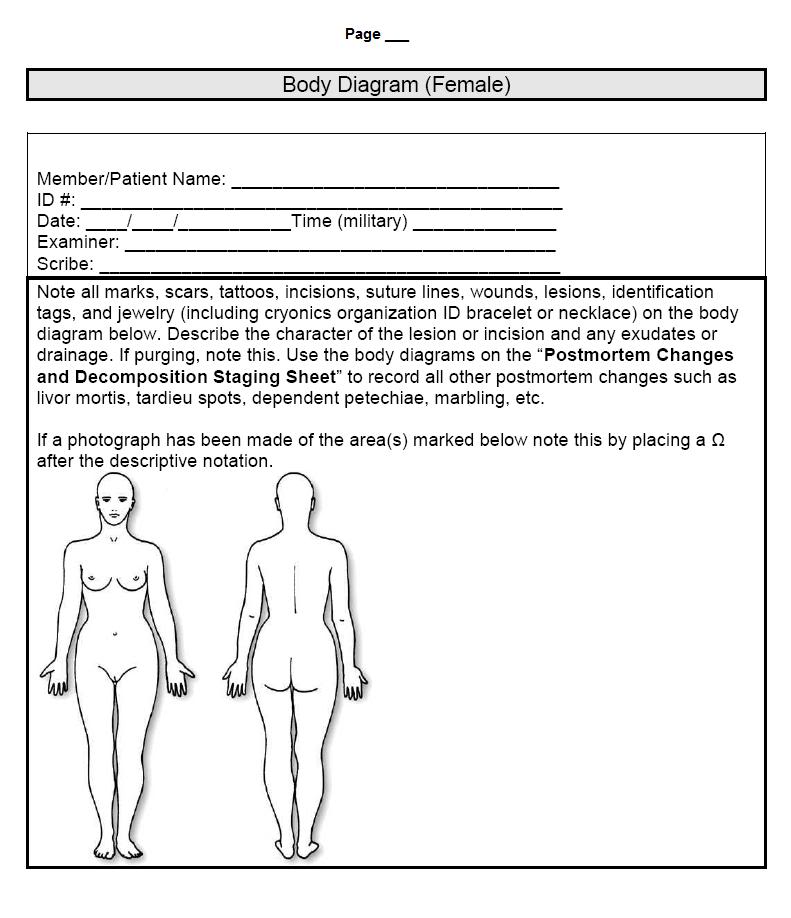

13) In the event the patient is discovered after the development of postmortem changes, such as rigor mortis or livor mortis (dependent lividity), it is sufficient to document these changes using ICPA form, auscultate the chest for 1-minute to establish absence of heart or breath sounds, and check for the absence of a carotid pulse. It is not necessary under such circumstances to repeat these observations or to wait the required 5-minutes for simple clinical determination of ICPA. Various presentations of livor mortis are shown in Figure 8. Livor mortis occurs when blood settles to the more dependent (lowest) areas of the body under the force of gravity where it distends the venules and the capillaries, and discolors the skin a violet or purplish red color. Livor mortis presents anywhere from twenty minutes to three hours after cardiac arrest, becomes “fixed” 4-5 hours post arrest, and peaks 6-12 hours after the onset of cardiac arrest. Lividity becomes fixed when the blood clots and/or when red cells undergo hemolysis and the tissues become stained with hemoglobin. Prior to this time, lividity may redistribute if the patient is moved. Dependent areas of the patient that are in contact with a surface and under pressure will not develop lividity. The presence of rigor or livor mortis is absolute contraindications to the initiation of CPR. If present, the location and extent of rigor or lividity should be noted on the Body Diagram that accompanies the Documentation of Cardiorespiratory Arrest Form (DCAF) present as an addendum to this document.

Caveats and Cautions

The above protocol offers no guarantees, but does provide substantial documentation of the patient’s actual condition using a nearly universal collection of accepted clinical criteria and specific methods to document irreversible cardiopulmonary arrest. “Irreversible” in this context must be understood to mean that it is either physically impossible to carry out resuscitation and/or that it is medically inappropriate or rejected as an assault on his person by the patient. Determination of medical contraindication to resuscitation must come from a physician(s) acting independently of any cryonics organization and without other conflicts of interest. Examples of the latter would be if such a physician were in any way involved with business entities related to cryonics, stands to take from the patient’s estate, and has personal or family relationships with the patient which could arguably cloud his judgment, or is paid a fee dramatically greater than the “usual and customary fee” for performing this service.

At a minimum, meticulous use of this protocol should help to protect the first responder who is giving last aid to the patient from any criminal or civil liability that might accrue as a result of erroneous or malicious accusations that he acted incompetently or recklessly in determining ICPA before proceeding with last aid measures, or even simply failing to notify and activate the EMS. Regardless of whether last aid measures are undertaken prior to pronouncement of medico-legal death; it is prudent to follow this protocol as completely as possible.

The Hazard of Electrocardiography

Restoration of any signs of life due to application of cryonics procedures, by definition, defeats the universal requirement of irreversibility or permanence which is inherent in all legally, medically and socially accepted definitions and criteria for determining and pronouncing death – from the Common Law definition as defined in Black’s Law Dictionary[14] to the commonsense definition as defined in Webster’s.[15] The criterion that the “permanence” or “irreversibility” of the loss vital signs obtain is also called for in the Harvard Criteria,[16] the American Medical Association’s guidelines,[8] the landmark Kansas statue defining death and the Uniform Declaration of Death Act[17]†.

Figure 9: The Premature Burial painted by Dutch artist Antoine Wiertz is as evocative today of the discomfort and anxiety felt by much of humanity when contemplating the prospect of ambiguity or error in determining when death occurs (and being certain of its permanence) as it was when Wiertz painted it in 1854.

Figure 9: The Premature Burial painted by Dutch artist Antoine Wiertz is as evocative today of the discomfort and anxiety felt by much of humanity when contemplating the prospect of ambiguity or error in determining when death occurs (and being certain of its permanence) as it was when Wiertz painted it in 1854.

What this means is that the decision to provide cardiopulmonary support at any time after the patient’s medico-legal death has been pronounced must, at a minimum, satisfy the criterion of irreversibility by not restoring any spontaneous signs of life including movement, agonal gasping, agonal respiration, return of mechanical or electrical activity in the heart (ECG), or return of electrical activity in the brain (EEG). Absent pharmacological intervention, it is inevitable that one, or even all of these signs, including consciousness and responsiveness to verbal stimuli, will return in a significant number of cryopatients subjected to prompt cardiopulmonary support.

While a waiting period of 5 or 10 minutes after cardiac arrest has been proposed as sufficient to prevent the return of cerebral function under normal clinical conditions,[12] this is by no means assured, and in many patients mild hypothermia and compensatory metabolic changes associated with peri-mortem pathologies that cause chronic ischemia or hypoxia (such as congestive heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) or a prolonged agonal period, may extend the window of cerebral recoverability well beyond this interval. Additionally, on no account will such a short waiting period, or even a waiting period as long as 20 minutes, insure that there is not a return of spontaneous cardiac activity,[18] agonal gasping, or reflexive movements in response to chest compressions or other manipulations which stimulate the spinal cord.[19],[20] Indeed, agonal gasping has been documented in one study to occur in 46% of arrests secondary to myocardial infarction or other primary cardiac causes, and in 32% of arrests from other etiologies. It is also important to note that there appears to be a “plateau effect” where there is less than one-third variability in survival with intact to moderate neurological disability between moderate (5-15 min) and prolonged (>15 min) periods of cardiac arrest.[18, 21] The best estimate of the upper limit of survival in cardiac arrest in the pre-hospital setting is based upon the observation that there are no survivors of normothermic arrest beyond an interval of 30 minutes from the time of witnessed collapse to initiation of basic cardiac life support (BCLS); although survival does occur in a few cases where the interval between arrest and BCLS is estimated to have been as long as 30 minutes.[22]

PEA Reconsidered

In many patients dying slowly the cessation mechanical contraction of the heart is followed by an interval of continued electrocardiographic activity; pulseless electrical activity (PEA), formerly known as “electromechanical disassociation” (EMD). The likely frequency of PEA in the population of cryopatients who experience slow deaths is the reason why ECG is never used as a monitoring or validating modality for determining or pronouncing medico-legal death (since some clinicians and nurses are unwilling to pronounce if PEA is present). The fact that PEA was likely to return in a significant fraction of patients undergoing CPR was deemed irrelevant since survival following PEA was considered virtually non-existent. Thus, in unmonitored cryopatients, PEA was considered simply an undesirable artifact of cardiopulmonary support which, especially if undetected (i.e., no ECG monitoring in place), was irrelevant. Indeed, in many hospitals in the U.S. terminal patients exhibiting PEA are still disconnected from the ECG monitor and then pronounced using clinical criteria.[23, 24]

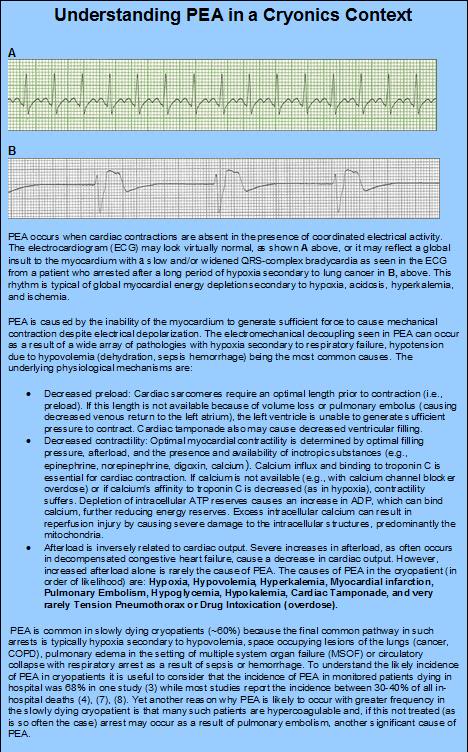

Figure 9: Understanding Pulseless Electrical Activity (PEA)

Figure 9: Understanding Pulseless Electrical Activity (PEA)

However, the medical perception, as well as the medical reality, of the incidence and prognosis of survival in cases of PEA in patients presenting with sudden cardiac death (SCD), as well as in patients suffering from other causes of cardiac arrest is undergoing a sea-change. In the past the PEA was exceedingly rare and its presence in either in-hospital or out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients was considered a “hopeless” cardiac rhythm that few if any patient’s survived.

For reasons not yet fully understood PEA has gone from being a rare presenting rhythm in cardiac arrest to the most common presenting rhythm in both in-hospital[23, 24] and out-of-hospital cardiac arrests (17). While the prognosis for survival of patients with PEA is still poor, it is by no means hopeless and appears to be steadily improving.[7],[25] The likely return of PEA during CPS in cryopatients may thus take on added medico-legal significance and the return of PEA, ventricular fibrillation, or other non-perfusing rhythms in cryopatients with implanted automatic defibrillators (increasingly likely as indications for use and application of these devices rapidly expands) would result in these devices administering counter-shocks with accompanying visible movement of the patient.

In the home hospice or ECF setting this problem can best be avoided by not using ECG monitoring in any form to either detect or verify the presence of medico-legal death. Rather, the use of conventional clinical criteria, technologically augmented such as by use of plethysographically acquired pulse and blood pressure or detection of cardiac arrest by a phonocardiomonitor using piezoelectric or conventional microphones is mandated.

High Risk Members and Continuous, Long-Term Digital Video and Audio Recording

Again, as a result of the exponential growth in computing power over the last 60 years, it is has become easily technically possible and affordable to continuously digitally record the entire interior of the average 2-3 bedroom home for periods of up to 2 weeks at a time on a single hard drive, at which point the recording is, in the normal course of affairs, overwritten one day at time so that, depending upon the quality of the recording desired, 1-2 weeks of continuous video surveillance of the entire dwelling is always available.

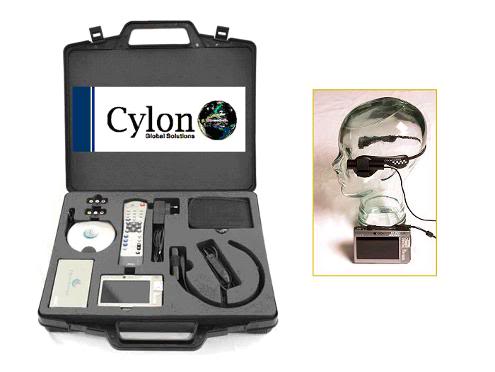

Figure 10: Cylon Body Worn Surveillance System. Wearable DVR: 16 x 9 screen size 720 x 576, resolution 4”, display video playback – MPEG-4 SP with stereo sound. Near DVD quality up to 720×480 @ 30 f/s (NTSC), 720×576 @ 25 f/s (PAL), AVI file format. WMV9 up to 352×288 @ 30 f/s, and 800 KBit/s. Exview Camera: Instant auto focus, Hi Resolution – 1 Lux 2 CIF image, rugged, waterproof, heat resistant and can be integrated into helmets and headwear. (Photos courtesy of The Audax Group, Plymouth, South Devon, UK, http://www.audaxuk.com/cylon/index.htm)

Figure 10: Cylon Body Worn Surveillance System. Wearable DVR: 16 x 9 screen size 720 x 576, resolution 4”, display video playback – MPEG-4 SP with stereo sound. Near DVD quality up to 720×480 @ 30 f/s (NTSC), 720×576 @ 25 f/s (PAL), AVI file format. WMV9 up to 352×288 @ 30 f/s, and 800 KBit/s. Exview Camera: Instant auto focus, Hi Resolution – 1 Lux 2 CIF image, rugged, waterproof, heat resistant and can be integrated into helmets and headwear. (Photos courtesy of The Audax Group, Plymouth, South Devon, UK, http://www.audaxuk.com/cylon/index.htm)

The advent of compact, reliable and wearable video recording equipment that could be deployed on the person(s) of those administering last aid to the patient, as well as the ready and affordable availability of continuous, forensically certifiable, digital video recording equipment, with the capability of uninterrupted recording of 2-weeks of ~250 to 450 frame per second, high quality color video (each terabyte of memory now costs approximately $400.00) have not been exploited by cryonics organizations‡. High capacity digital video recorders which allow for fast and easy data searches, provide self-schedule management, automatic data backup, e-mail event alert, and offer IP Address Dispatch (for use with dynamic IP), and control of multiple systems from a remote location[26] are now in wide use in law enforcement, government and business . In-house and in-field (mobile) versions of forensic video systems are rapidly becoming the standard of practice for law enforcement where they are used to protect police officers against accusations of abuse or misconduct.[27],[28] One example widely used by law enforcement around the world is the Cylon Body Worn Surveillance System (Figure 10). The unit consists of a compact, waterproof DVR, and a high resolution color camera (worn on a headset) as shown in Figure 4, above. The DVR can store 400 hours of Mpeg-4 quality full color video and audio recording on it 100 GB hard drive and has a battery life of ~12-hours at its peak, 30 fps recording rate. Since the unit is built for law enforcement it has time/date stamping and event marking capability as well as sophisticated graphical user interface software which allows for rapid search and retrieval of recorded material.[29]

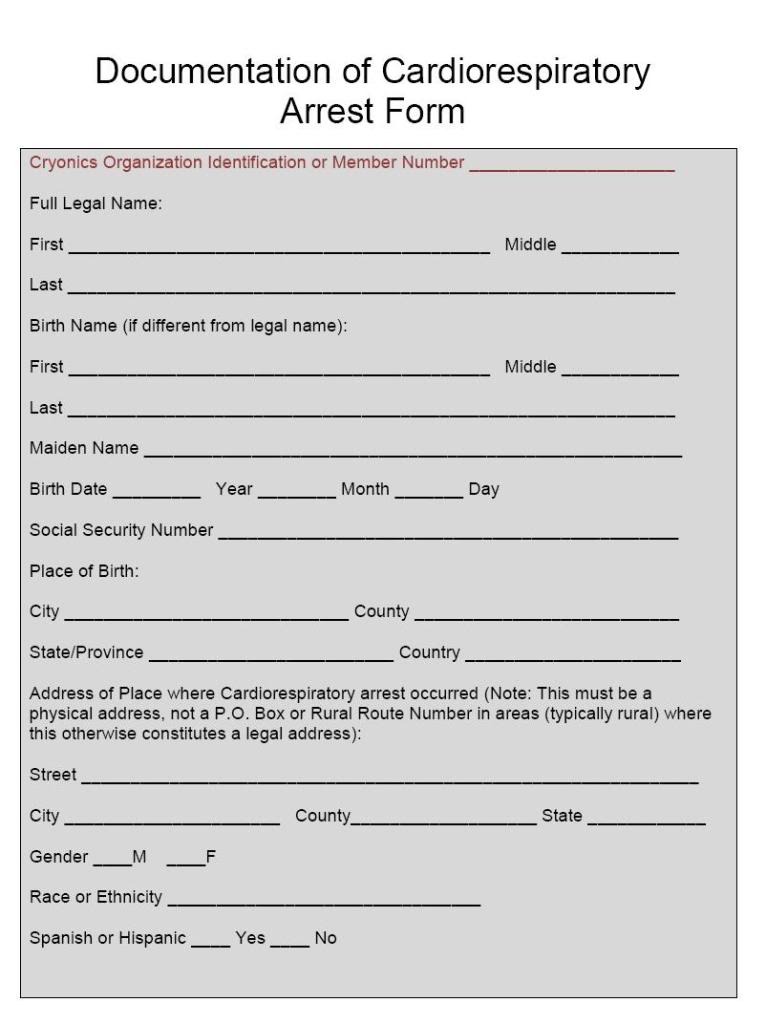

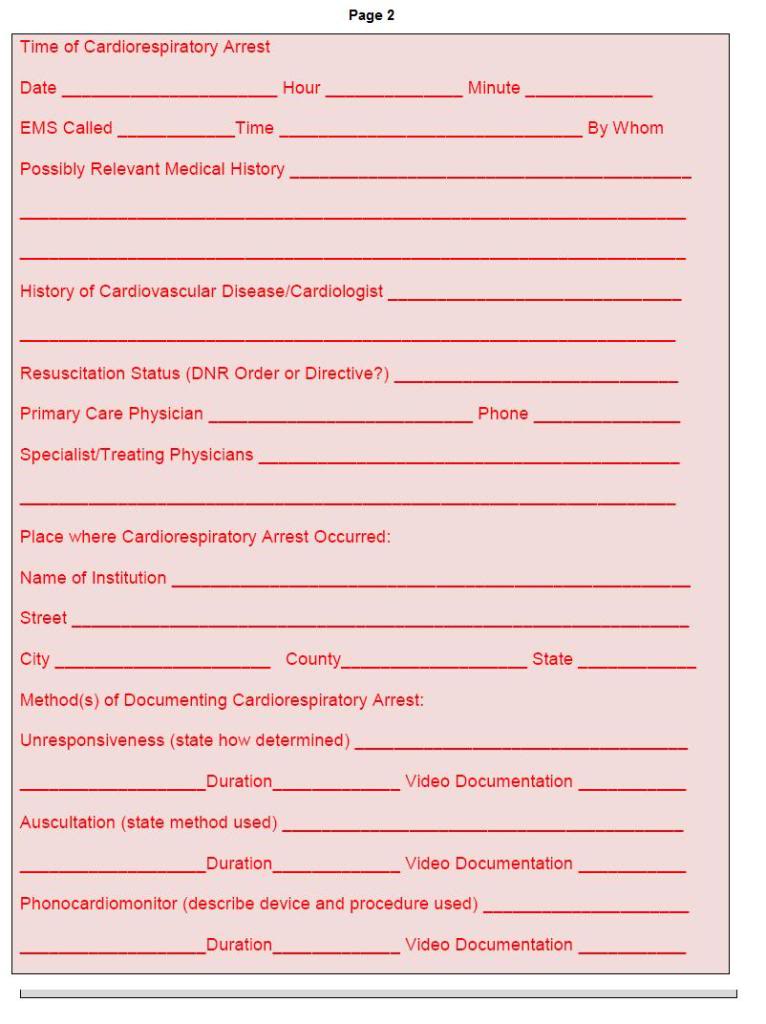

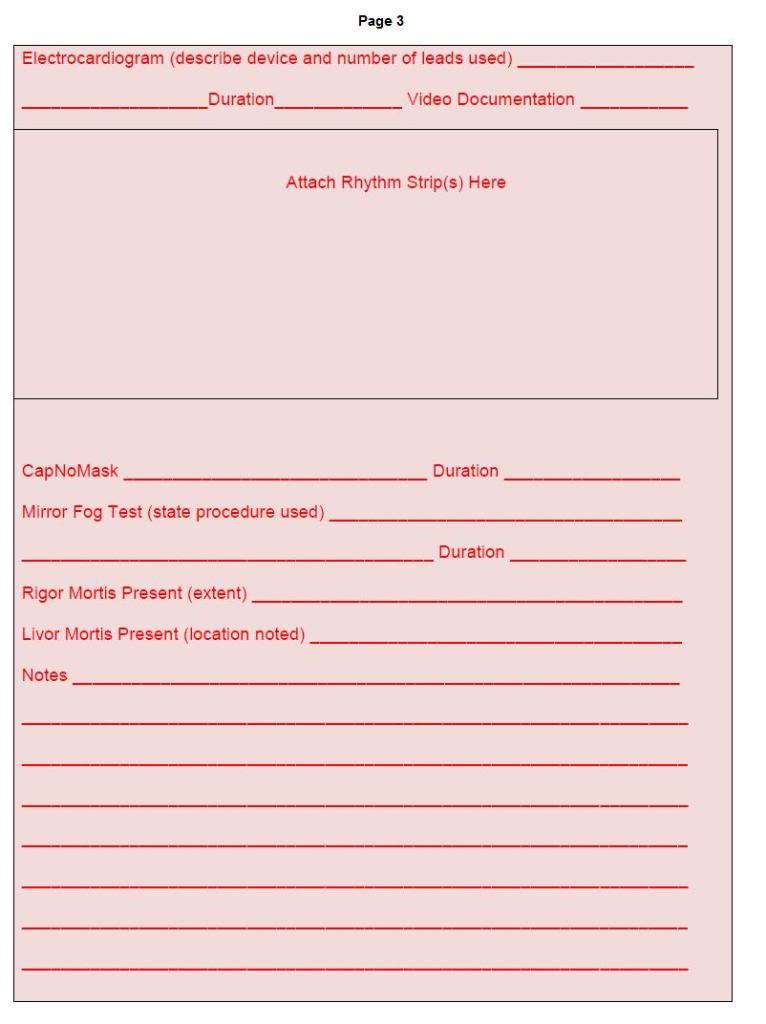

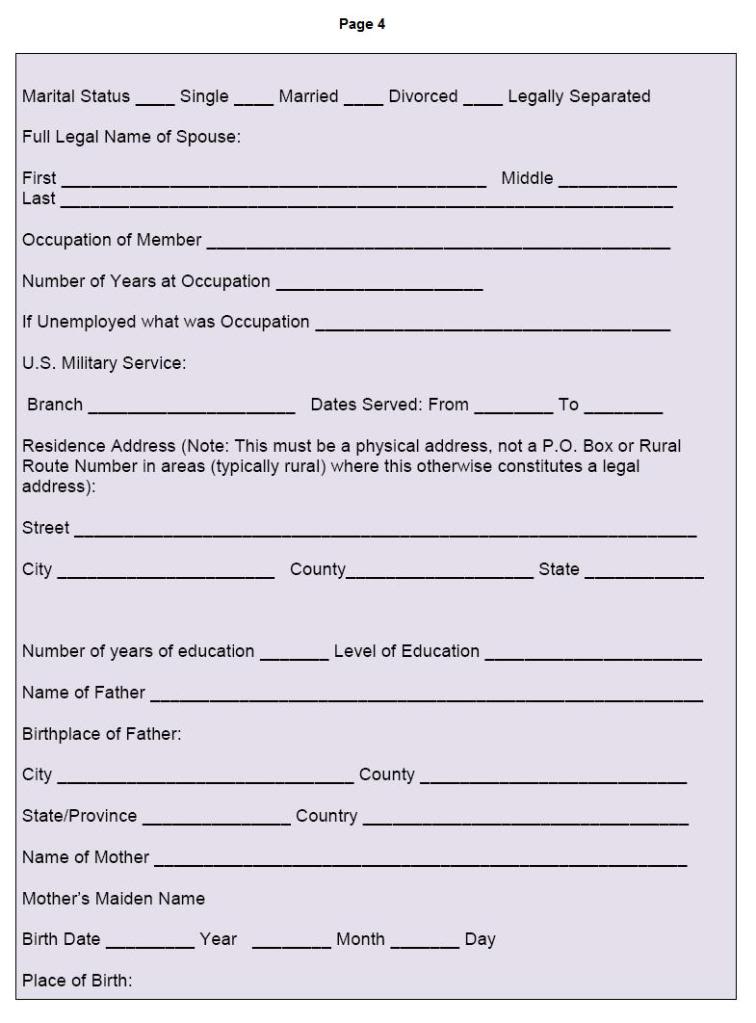

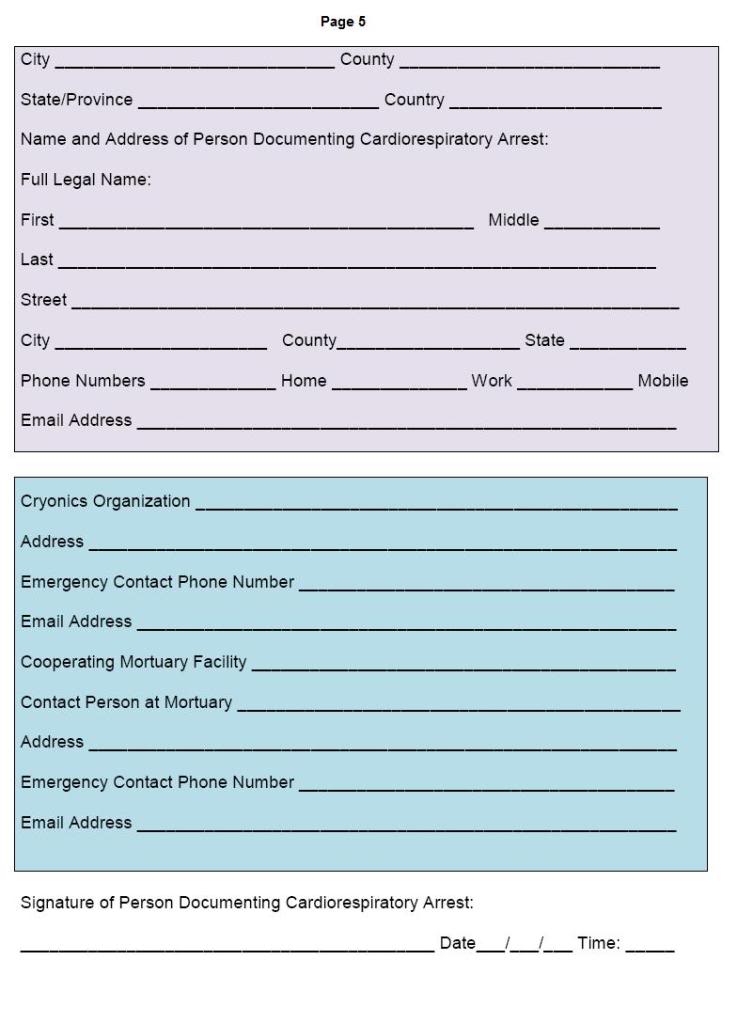

Documentation of Cardiorespiratory Arrest Form (DCAF)

The Documentation of Cardiorespiratory Arrest Form follows the format of data collection used for death certificates in all 50 US States, as well as in Canada and the UK. The information requested on the DCAF is absolutely critical to have available as soon as the patient’s physician or the C/ME arrive. In order for a death certificate to be issued, which is a necessary prerequisite to release of the patient’s body to a cryonics organization or its representative mortician or Funeral Director, all of this information must be available to the physician or mortician filling it out. Failure to have this information at hand and in an organized form can and has resulted in significant delays in the release of cryonics patients of to cryonics organizations resulting in many hours of additional ischemic time. It is strongly recommended that all persons with cryonics arrangements have a DCAF filled out in advance and stored in their Last Aid Emergency Response kit.

Addendum: Documentation of Cardiorespiratory Arrest Form (DCAF):

End of Part 2

End of Part 2

Footnotes

† Some may find this statement disagreeable and will point to the 1981 report by the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research entitled Defining Death: A Report on the Medical, Legal and Ethical Issues in the Determination of Death, or to the diverse and wildly different state laws for determining death, which, at last count, came in 27 different flavors, as evidence of statutory criteria. In fact, close reading of all these laws devolves to the final common denominators that death “constitutes an irreversible cessation of vital functions” as determined by physicians or others so authorized “”based on ordinary standards of medical practice” or “according to usual and customary standards of medical practice” or “in accordance with reasonable medical standards” or “in accordance with accepted medical standards”… In short, there are no discrete diagnostic modalities or procedures specified by law.

† An excellent review of the medico-legal definition of death and the problem presented by the requirement for permanence or irreversibility can be found in Persons, Humanity, and the Definition of Death by Lizza, JP. Persons, Humanity, and the Definition of Death. Boston: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2006..

‡ An upend example is the Toshiba EVR RAID-5 32 channels DVR 480 fps (15fps per cam) security video recorder which can accommodate up to 4 terabytes of memory and retails (1 terabyte) for just under $6,000. Such a system would allow continuous video surveillance of every room of a large residence with 6-weeks of audio-video storage capacity.

References

1.Powner D, Ackerman, BM, Grenvik, A.: Medical diagnosis of death in adults: historical contributions to current controversies. Lancet 1996, 348(2):1219-1223.

2.Pearle M: Texas law on pronouncement of death. Healthtexas 1993, 49(1):8.

3.Das C: Death certificates in Germany, England, The Netherlands, Belgium and the USA. Eur J Health Law 2005, 12(3):193-211.

4.Cole D: Statutory definitions of death and the management of terminally ill patients who may become organ donors after death. Kennedy Inst Ethics J 1993, 3(2):145-155.

5.Doig C, Rocker, G.: Retrieving organs from non-heart-beating organ donors: a review of medical and ethical issues. Can J Anaesth 2003, 50(10):1069-1076.

6.Marchand L, Kushner, KP. : Death Pronouncement: survival tips for residents: http://www.aafp.org/afp/980700ap/rsvoice.htmlAmerican Family Physician 1998, N/A(July).

7.van Walraven C, Forster, AJ, Stiell, IG.: Derivation of a clinical decision rule for the discontinuation of in-hospital cardiac arrest resuscitations. Arch Intern Med 1999, 159:129-134.

8.AMA: Guidelines for the determination of death. . JAMA 1981, 246(19):2184-2186.

9.Brook N, Waller, JR, Nicholson, ML.: Nonheart-beating kidney donation: current practice and future developments. Kidney Int 2003, 63(4):516-529.

.

10.Capron A, Kass, LR.: A statutory definition of the standards for determining human death (Kans Stat Ann (suppl 197 1):77-202.). Univ Pa L Rev 1978:87-118.

11.Daemen J, de Wit, RJ, Bronkhorst, MW, Yin, M, Heineman, E, Kootstra, G.: Non-heart-beating donor program contributes 40% of kidneys for transplantation. Transplant Proc 1996, 28(1):105-106.

12.DeVita M, Snyder, JV., , Jun;: Development of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center policy for the care of terminally ill patients who may become organ donors after death following the removal of life support. Kennedy Inst Ethics J 1993, 3(2):31-43.

13.Heidenreich C, Weissman, DE.: Death Pronouncement and Death Notification: What the Resident Needs to Know: http://www.journeyofhearts.org/kirstimd/AMSA/pronounce.htm. In.: EPERC (End-of-Life Physician Education Resource Center). 2000

14.Garner BA: Black’s Law Dictionary

Thompson West; 2004

15.Webster’s Revised Unabridged Dictionary Springfield: G & C. Merriam Co.; 1913.

16.Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School to examine the definition of brain death: a definition of irreversible coma. . JAMA 1968, 205:337-340.

17.Uniform Determination of Death Act. In. Chicago: National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws 1981.

18.Vukmir R, Bircher,, N, Radovsky, A, Safar, P.: Sodium bicarbonate may improve outcome in dogs with brief or prolonged cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med 1995, 23:515-522.

19.Jain S, DeGeorgia, M.: Brain death-associated reflexes and automatisms. Neurocrit Care 2005, 3(2):122-126.

20.Dosemeci L, Cengiz,. M, Yilmaz, M, Ramazanoglu, A., : Frequency of spinal reflex movements in brain-dead patients. 2004, 36(1):17-19.

21.Clark J, Larsen, MP, Culley, LL, Graves, JR, Eisenberg, MS.: Incidence of agonal respirations in sudden cardiac arrest.

. Ann Emerg Med 1992 21(12):1464-1467.

22.DeBehnke D: Resuscitation time limits in experimental pulseless electrical activity cardiac arrest using cardiopulmonary bypass. Resuscitation 1994 27(3):221-229.

23.Parish D, Dane, FC, Montgomery, M, Wynn, LJ, Durham, MD, Brown, TD.: Resuscitation in the hospital: relationship of year and rhythm to outcome. Resuscitation 2000, 47:219-229.

24.Parish D, Dinesh, KM, Francis, C, Dane, C.. Success changes the problem: Why ventricular fibrillation is declining,why pulseless electrical activity is emerging, and what to do about it. Resuscitation 2003, 58 31-35.

25.Stiell I, Wells, GA, Field, BJ, et al.: Improved out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survival through the inexpensive optimization of an existing defibrillation program. JAMA 1999, 281:1175-1181.

26.Toshiba EVR Series Security DVR With 4 Terabytes of Memory [http://www.mp50.com/8070/DVRUPG1RT525TR5.asp]

27.Castro H: Police cars get digital cameras; Seattle department first to use new wireless capability. In.: Seattle Post-Intelligencer Reporter

2004.

28.Digital video recorders give more reliable, accurate footage to police March, 2007. [http://www.policeone.com/police-products/vehicle-equipment/in-car-video/articles/99438/]

29.Cylon Body Worn Surveillance System [http://www.intelcam.co.uk/]

ahn S, Sullivan, FJ, DeLuca, AM, Bacher, JD, Liebmann, J, Krishna, MC, Coffin, D, Mitchell, JB. Hemodynamic effect of the nitroxide superoxide dismutase mimics. Free Radic Biol Med 1999;27((5-6)):529-35.

25.Darwin M. Transport Protocol for Cryonic Suspension of Humans, Fourth Edition. 1990.

mike, do you ever get drunk? ever sit on the porch with a friend and get really wasted?

No, but don’t stop reading, yet. This is the most thoughtful, and probably the most honest question you’ve asked here. It is certainly the most insightful.

If I understand it, what you are asking is, “Do you every turn off the ‘razor edged analytical part’ of your mind, and just live in the moment?” The answer to that is, “Yes, but not with alcohol.” Despite being raised in a home with strong European influences, where wine was frequently served with dinner, and highballs and beer were a common, if not daily late evening and weekend beverage, I loathe the way alcohol makes me feel. I had “European style” access to alcohol as a kid; a tiny glass of wine with dinner, if I wanted it, and the ability to take a sip of alcoholic drinks to see what they tasted like. As a result, it was not forbidden fruit, and when my friends began to drink in their late teens, I tried to as well. I hated it.

As a kid, I would often walk into utility poles, leave my books at the market while buying candy on my way home from school, and leave the lunch counter at the Five and Dime without paying – all because I forgot. I lived mostly in other worlds and inside my head, and this was bloody dangerous, because I was almost as equally likely to step off the curb into oncoming traffic. If the many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics is correct, then in the vast majority of those worlds, little Mike Federowicz (now also known as Mike Darwin) was long ago run over and maimed, or killed. I had to work very hard to overcome “living in my head,” and to learn to live in the real world. Alcohol fogged my ability to function in reality, without giving me the warm, pleasant high, and the relief from anxiety that it does most people.

As a young gay man with a modest social life, I tried quite hard to take up drinking wine in my mid-20s. Drinking, and being mildly intoxicated, are very important socially – probably more important than food is, in this respect, especially if you were gay at that time: bars were pretty much the only social venue. I had also learned that people who are drinking together “go somewhere” that someone who doesn’t drink, can’t follow. And this is true, even if they have just a couple of drinks; being a teetotaler, to use a quaint and dated term, cuts you off from that journey, and is very socially isolating.

I needed a cleaner drug, and it wasn’t until I was hospitalized in the late 1970s, that I found it, or more precisely, them: benzodiazepines. I was bleeding from a peptic ulcer and the H2-receptor antagonists were band new drugs. I’d been bleeding every spring and fall like clockwork for several years, and swallowing what must have been liters of Maalox and Riopan, to little good effect. Finally, I was bleeding badly enough that I was hospitalized, started on a Tagamet (cimetidine) IV drip, and given Valium round the clock for a week. For the first time in my entire remembered life, the racket was gone. It was like I had lived my whole life with the radio blaring, horns honking, people talking loudly to each other, dogs barking…and then there was SILENCE.

Much more specific and potent drugs in this class have been developed since. And I have to handle them with extreme care. On the up side, I still don’t like the “drunken” obliteration of consciousness you can get with alcohol, and which you can approach with benzos.”

That’s wasn’t to be my ticket to “enlightenment.”

To go where you go, or I presume you go, I had to find another route. There’s nothing very remarkable about it, and isn’t illegal or immoral, but I don’t choose to share it here. Even I have some things I would keep to myself (and to those who I would trust enough to get stinking drunk with, if I drank). Because in addition to getting to a place where you just “are” and you are without thoughts or cares, and are just living; and feeling damn good about it, that is best done with others. It is a vulnerable place, a vulnerable time, and it is unarguably best shared with those who are going there with you, and in whom you trust. – Mike Darwin

This is all the more reason why some kind of micro-environment (social and medical) is needed for people nearing deanimation. The medical milieu is extremely bureaucratic. As per a previous posting on this issue, it will be difficult to convince the medical establishment to allow for “controlled” deanimation while protecting the brain from ischemic injury.