By Mike Darwin

Introduction

The lighting-speed evolution of information technology has made new tools available to cryonics that would formerly have been so costly, that only the largest enterprises could have made use of them. And recently, a new technology has emerged that arguably no enterprise, with the possible exception of nation-states, could have mustered the resources to access. In December of 2010 Google, without fanfare, and with virtually no media announcements, released a search tool it calls Ngram.

For the better part of the past decade Google has been “quietly” scanning millions of books, with the objective of scanning the entire written human library by the mid-21st century. Their progress to date is rumored to be in the range of 15 million books, or ~12% of all books ever published. Beyond an acknowledgement from Google that they are using optical character recognition technology, other details of how they are achieving this feat has been a source of intense speculation, as has the rate at which their progress is increasing (as a result of improved mastery of the “learning curve,” and continued technological advances in computing, imaging and robotics).

What can you do with ~ 15.2 million books and ~ 25 billion digitized words in English, French, Spanish, German, Russian, Chinese and Hebrew? The obvious thing would be to sell the books in digital format on line. Almost all of the books that have been written are not only out of print; they are often notoriously difficult and time consuming to access. And when they are accessed, they become vulnerable to loss. But of course, copyright and other legal issues create substantial handicaps to such a direct sales approach, although Google appears to be working to successfully overcome this.

Culturomics: A New Discipline Emerges

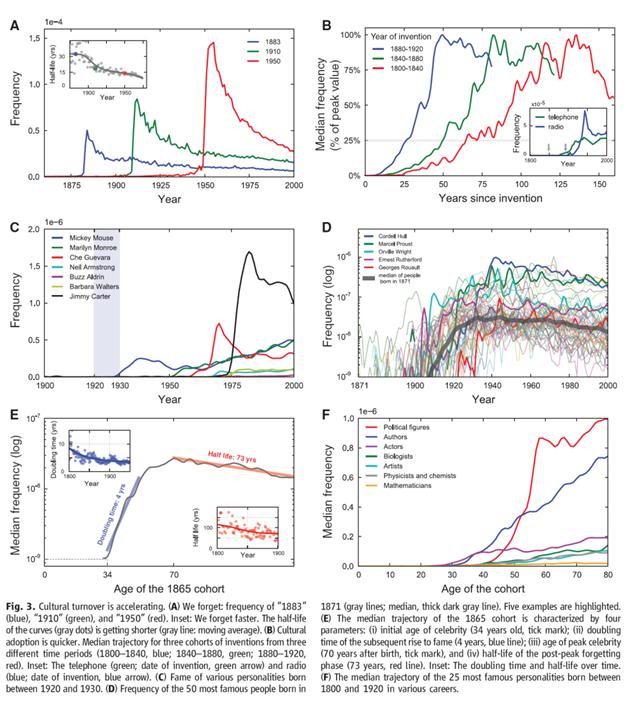

So, book “sales” and book preservation aside, what can you do with all that data? As it turns out, you can found a brand new discipline, “culturomics,” that makes any survey mechanism or market research antiquated, for determining the durable penetration and life history of an idea, product, or person in human intellectual history. Just 3 months ago, Michel, et al., published the paper founding the new discipline of culturomics in Science, entitled, “Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books.”[1] The authors selected 5,195,769 digitized books (~4% of all books ever published) from Google’s cache of 15 million (and growing) based upon the quality of the scans, and their ability to obtain the necessary relevant metadata, such as the year and place of publication. This is a staggering amount of data, and even using large numbers of humans to perform searches, the sheer quantity makes it impossible. As the authors point out, if a single individual “were to try to read only English-language entries (in the corpus of the books they used) from the year 2000 alone, at the reasonable pace of 200 words/min, without interruptions for food or sleep, it would take 80 years.” To get an idea of what is possible with this technology, look at Figure 1, below, which is taken from the Michel, et al., Science article.

Figure 1: The enormous power of culturomics to track not only the penetration of ideas in a culture, but their durability and dynamics, is illustrated above. It is also possible to measure how rapidly ideas are adopted, how rapidly they are forgotten or discarded, and how they interact with each other, all as function of time, and even place.

Examples of the kinds of data than can be mined using this technology and the Google Books database are, as shown in Figure 1, above, that the names of celebrities faded twice as fast in the mid-1900s and they did in the early 1800s. Similarly, while the mean time to adoption of a novel technology required 66 years in the early 1800s, by 1880 that number had declined to 27 years. The common perception that “things are moving faster and faster” in terms of the turnover rate of cultural content is well supported by these data. Contrawise, it is also possible to evaluate the extent to which ideas can be suppressed in a culture, either directly by the actions of nation-states, or indirectly by social, cultural and political trends that operate as a result of the introduction of new ideas, the rise and fall of religious or political ideologies, or just about any other factor you can identify, and subject to measurement.

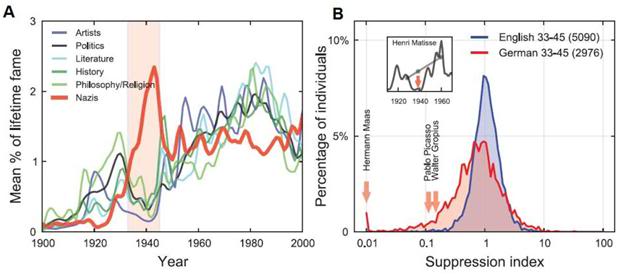

Figure 2: Effect of political, ideological and nation-state enforced suppression on “targeted” individuals, and on intellectual activity in general, during the period of Nazi domination of Germany.

Not surprisingly, one of the examples Michel, et al., chose as an example of “suppression” was the savage censorship in Nazi Germany that began with the book burnings of 1933, and ended with the defeat of the Third Reich in 1945. They tracked the names of a selected group of individuals known to be distasteful to the Nazi Party, for instance the Impressionist and Abstract painters Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, as well as the architect Water Gropius. Not unexpectedly, the data showed a huge suppression of the mention of these men and their work in German language publications for the duration of the Third Reich (Figure 2B, above). However, unexpectedly, and perhaps far more interestingly, they found that the period of Nazi domination of the culture was associated with a global depression of virtually all artistic, cultural, political and literary activity within the Third Reich (Figure 2A, above). The thick red line in 2A, above, is the frequency of the occurrence of the word “Nazi” in German language books during this period. Obviously, it was a good time for that word – so good, that perhaps there was an insufficient supply of a, z, n, and i type to allow for others works to be published during this time.

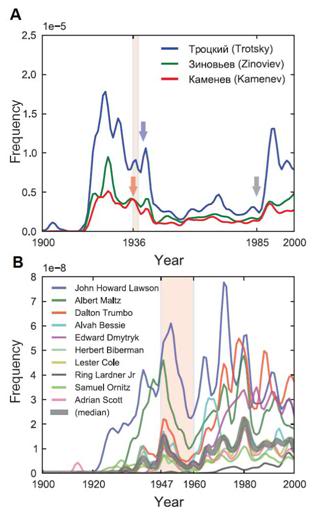

Figure 3: (at left) Impact of two nation-states and their ideologies on the frequency of mention or credits given to individuals considered ideologically dangerous. In the former Soviet Union, in Russian texts (A), (with noteworthy events indicated): Trotsky’s assassination (blue arrow), Zinoviev and Kamenev executed (red arrow), the Great Purge (red highlight), and perestroika (gray arrow). In the United States (B) during the McCarthy era and the Cold War, a group of film directors and screen writers, the “Hollywood Ten,” were blacklisted (red highlight) from U.S. movie studios. Their visibility in print declined (median: thick gray line) and none were credited on any motion picture in the US, until the 1960’s.

Figure 3: (at left) Impact of two nation-states and their ideologies on the frequency of mention or credits given to individuals considered ideologically dangerous. In the former Soviet Union, in Russian texts (A), (with noteworthy events indicated): Trotsky’s assassination (blue arrow), Zinoviev and Kamenev executed (red arrow), the Great Purge (red highlight), and perestroika (gray arrow). In the United States (B) during the McCarthy era and the Cold War, a group of film directors and screen writers, the “Hollywood Ten,” were blacklisted (red highlight) from U.S. movie studios. Their visibility in print declined (median: thick gray line) and none were credited on any motion picture in the US, until the 1960’s.

However, lest we become too self-satisfied at the poor performance of the Nazis, we would do well to take a look at Figure 3. The suppression of the names of Trotsky, Zinoviev, and Kamanev, as they fell out of favor in the former Soviet Union, and the suppression of the (visible) work product of the “Hollywood Ten,” should clearly demonstrate that this kind of activity is a commonplace across cultures. The blacklisting of the Hollywood Ten, and many other creative talents in Hollywood, occurred as a result of these writers and directors being cited for being in contempt of Congress for refusing to give testimony to the House Committee on Un-American Activities. The executives of all of the principal movie studios at that time, acting under the umbrella of their trade association, the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), fired these artists in the now infamous “Waldorf Statement,” issued by MPAA President Walter Johnson from the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York City on 03 December, 1947.

Culturomics and Cryonics

Culturomics is powerful stuff, really powerful stuff, and I believe it can be of considerable use in cryonics, especially as the Google database expands into periodicals.[1] I have just begun to explore this tool, and while I am certainly no expert in this area, my preliminary forays have proven interesting to me, and I hope will be of interest to you, as well. Best of all, you can do your own analyses by going to: http://ngrams.googlelabs.com/ A few words of caution: search terms are case sensitive, should be comma separated (no spaces between commas and the next search term), and the choice of search terms can dramatically affect outcome; for instance “Jesus “vs. “Jesus Christ.”

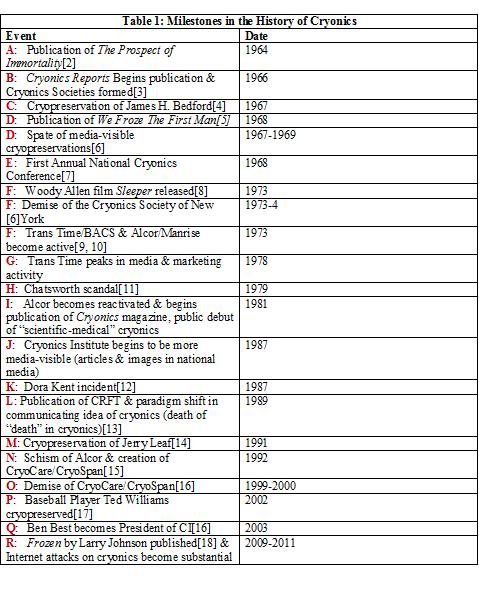

In order to minimize injecting more bias into my analysis than that which will necessarily already be there, the first thing I did before attempting any interpretation of the Ngram data relating to cryonics, was to decide what events in the history of cryonics I thought were most important, and that were also publicly visible (i.e., documented in cryonics, or other publications). This is necessarily a subjective thing, but I felt it was important to do this before looking at the Ngram generated data. My list of significant events is in shown in Table 1, above.

In order to minimize injecting more bias into my analysis than that which will necessarily already be there, the first thing I did before attempting any interpretation of the Ngram data relating to cryonics, was to decide what events in the history of cryonics I thought were most important, and that were also publicly visible (i.e., documented in cryonics, or other publications). This is necessarily a subjective thing, but I felt it was important to do this before looking at the Ngram generated data. My list of significant events is in shown in Table 1, above.

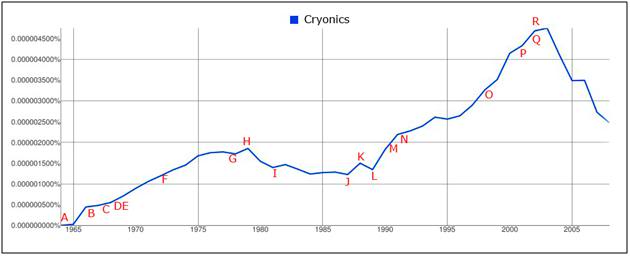

Figure 4: The frequency of the occurrence of the word cryonics in all books published from the period 1965 through 2005, as determined by a Google Ngram search. (A) Publication of The Prospect of Immortality in 1964, (B) Cryonics Reports Begins publication and the various Cryonics Societies are formed, (C) Cryopreservation of the first man, James H. Bedford, (D) Publication of We Froze The First Man, and a spate of media-visible cryopreservations, (E) First Annual National Cryonics Conference held in 1968 attracts widespread media attention, (F) In 1973, Trans Time, Inc., (TT) and its partner non-profit, the Bay Area Cryonics Society (BACS) become active in the San Francisco Bay Area and attract national media attention, while Alcor and its for profit Manrise Corporation, become active in Southern California, developing much of the perfusion platform used by TT, (G) Trans Time peaks in media & marketing activity, having launched the bulk of its marketing efforts by this time, (H) The Chatsworth Scandal becomes public, resulting in strongly negative international media coverage, (I) Alcor becomes reactivated, begins publication of Cryonics magazine and there is the public debut of “scientific-medical” cryonics, with images released to the media showing cryonics as a medical procedure; photos of cryonics patients are no longer used for promotional purposes, (J) The Cryonics Institute begins to be more media-visible with articles and images appearing in the national media. Emphasis on CI’s lower price begins to become a source of comparison with Alcor, (K) the Dora Kent incident occurs with a resulting firestorm of international media coverage, followed by the Thomas Donaldson lawsuit against the Attorney General of the State of California, (L), Alcor shifts the paradigm of communicating cryonics to the public by redefining death and providing extensive, and technically detailed information packages to media, and to those members of the public who inquire; Cryonics Reaching for Tomorrow is published, and used as the core promotional tool by Alcor, (M) Jerry Leafs experiences sudden cardiac arrest from a heart attack in 1991, and is cryopreserved, (N) Schism of Alcor, and subsequent creation of CryoCare and CryoSpan as competing cryonics organizations in 1992, (O) Demise of CryoCare and CryoSpan in 1999-2000 (effective end of scientific cryonics), (P) Baseball Hall of Famer Ted Williams is cryopreserved by Alcor in 2002, (Q) Ben Best becomes President of the Cryonics Institute, (R) A story in Sports Illustrated alleges Williams was mistreated at Alcor, the story become international in scope, and the ongoing litigation amongst the family over issue of Williams’ cryopreservation is further highlighted .

Figure 4: The frequency of the occurrence of the word cryonics in all books published from the period 1965 through 2005, as determined by a Google Ngram search. (A) Publication of The Prospect of Immortality in 1964, (B) Cryonics Reports Begins publication and the various Cryonics Societies are formed, (C) Cryopreservation of the first man, James H. Bedford, (D) Publication of We Froze The First Man, and a spate of media-visible cryopreservations, (E) First Annual National Cryonics Conference held in 1968 attracts widespread media attention, (F) In 1973, Trans Time, Inc., (TT) and its partner non-profit, the Bay Area Cryonics Society (BACS) become active in the San Francisco Bay Area and attract national media attention, while Alcor and its for profit Manrise Corporation, become active in Southern California, developing much of the perfusion platform used by TT, (G) Trans Time peaks in media & marketing activity, having launched the bulk of its marketing efforts by this time, (H) The Chatsworth Scandal becomes public, resulting in strongly negative international media coverage, (I) Alcor becomes reactivated, begins publication of Cryonics magazine and there is the public debut of “scientific-medical” cryonics, with images released to the media showing cryonics as a medical procedure; photos of cryonics patients are no longer used for promotional purposes, (J) The Cryonics Institute begins to be more media-visible with articles and images appearing in the national media. Emphasis on CI’s lower price begins to become a source of comparison with Alcor, (K) the Dora Kent incident occurs with a resulting firestorm of international media coverage, followed by the Thomas Donaldson lawsuit against the Attorney General of the State of California, (L), Alcor shifts the paradigm of communicating cryonics to the public by redefining death and providing extensive, and technically detailed information packages to media, and to those members of the public who inquire; Cryonics Reaching for Tomorrow is published, and used as the core promotional tool by Alcor, (M) Jerry Leafs experiences sudden cardiac arrest from a heart attack in 1991, and is cryopreserved, (N) Schism of Alcor, and subsequent creation of CryoCare and CryoSpan as competing cryonics organizations in 1992, (O) Demise of CryoCare and CryoSpan in 1999-2000 (effective end of scientific cryonics), (P) Baseball Hall of Famer Ted Williams is cryopreserved by Alcor in 2002, (Q) Ben Best becomes President of the Cryonics Institute, (R) A story in Sports Illustrated alleges Williams was mistreated at Alcor, the story become international in scope, and the ongoing litigation amongst the family over issue of Williams’ cryopreservation is further highlighted .

The next step was to do the Ngram plot of the word cryonics, and then apply the dates, the results of which you see in Figure 4, above. While the impact of some of the events I chose is arguable, in a number of instances the data seem to confirm these events as having had a material effect on the penetration of word (and thus presumably the idea) of cryonics in books written from 1964 to 2005, the period for which Ngram data are available. The publication of The Prospect of Immortality in 1964, and the subsequent period of public cryonics promotional activity that continued up until 1969, are clearly visible in A-E. The next fairly unequivocal uptick in activity is associated the public debut of Trans Time, Inc., in 1973, as represented by G in Figure 4. Trans Time aggressively marketed itself and cryonics during the interval of 1974-1960, and was the primary source of media images for cryonics from 1973, until approximately 1982.

Unfortunately, the next unequivocally significant event was H in Figure 4, which represents the loss of the 9 Cryonics Society of California (CSC) patients at Oakwood Memorial Park Cemetery in Chatsworth, California; a fact which became public in 1979. There was a firestorm of media activity surrounding both the discovery of the decomposed remains at Chatsworth, and the subsequent civil trial, which resulted a large judgment against former CSC President Robert F. Nelson, and the mortician who assisted him, Joseph Klockgether.

While those of us involved in cryonics at the time knew this event had an enormous negative impact on cryonics, I confess I am stunned to see it so dramatically confirmed, as measured by a variable so removed from day-to-day media activity, such as the publication of books, and the words (and thus subjects) discussed in them! While we cryonicists were aware that the number of people being cryopreserved declined to almost nothing during this interval, and we were inescapably aware of the effect the Chatsworth debacle had on the opinion the public held of cryonics (because we received so much angry and ridiculing criticism), I don’t believe that any of us understood the sheer magnitude of the negative impact on cryonics it had in terms of the culture as a whole. That is clearly apparent in the culturomic measurement during the intervals represented by H- L in Figure 4, and interestingly, in Figure 6, below.

I think it’s fair to argue that the events during the time interval of 1981 through through ~1991 (I-L), were in significant measure responsible for the post-Chatsworth recovery of cryonics’ cultural impact. There also seems to be a clear negative effect resulting from the schism of Alcor in 1992 – but subsequent events, including the dissolution of CryoCare and its brother organization CryoSpan, in 1999-2000 (M-O), seem to have had no impact.

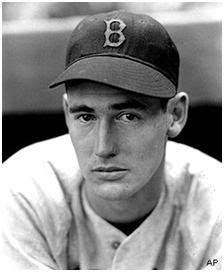

The next unequivocally significant event would appear to be the cryopreservation of Baseball Hall of Famer Ted Williams, in 2002 (P). After the expected lag time, there is a surge of cultural impact for cryonics, followed by a sharp downturn in 2003 (R), which is undoubtedly a function of the negative publicity concurrent with the publication of the Sports Illustrated and ESPN exposes’, which happened at this time. Presumably, the resulting loss of credibility of cryonics as a serious idea – or at least one which could be used in novels, and discussed in non-fiction (science oriented) books without evoking concerns over censure, or negative media stereotypes interfering with it being taken seriously as a plot mechanism, resulted from this period of sustained and adverse publicity (which continues to this day).

The “Splendid Splinter:” Ted Williams (right).

By the measure of culturomics, the immediate impact of the cryopreservation of Ted Williams, under circumstances which called into question the veracity and justification for the procedure, was incredibly damaging. While there are no data beyond 2005, if the downturn in activity seen in Figure 4 is sustained for even a year or two longer, then this event will rank with Chatsworth as being one of the most injurious things to happen cryonics in its 47 year long history. One wonders if the Directors and Officers of Alcor at that time, who were so seduced by Williams’ celebrity, and the perceived opportunity for favorable publicity for Alcor and cryonics, will be held accountable for abandoning the long standing and time tested procedures for accepting at-need cryonics cases? While there is truth to the old adage that “any press is good press,” these data are proof positive that really bad press, particularly when it alters the public perception of the morality of an undertaking, is nothing short of a disaster. By contrast, the Dora Kent incident, in which cryonics personnel were wrongly (but nevertheless very publicly) accused of murdering a patient, and indeed of decapitating her whist she was still alive, had essentially no adverse impact, and appears to have resulted in a favorable culturomic effect on cryonics. The difference presumably being that in the Dora Kent case, the follow-on to the negative media firestorm, was a general realization that the whole affair was consequence of incompetent blundering on the part of law enforcement. In the Williams case, the internecine battle amongst family members, and the poor quality of documentation submitted by his son and daughter to demonstrate his personal desire for cryopreservation, clearly left the public, and that subset of it that writes books, with grave concerns.

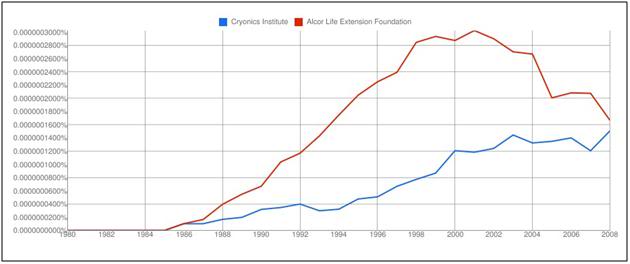

Figure 5: Ngram of the words” Cryonics Institute”(CI) plotted against that of “Alcor Life Extension Foundation” (Alcor). As can be seen, Alcor is apparently in very serious trouble, and in all likelihood CI has become the more commonly mentioned cryonics organization in the interval between 2008 (when they are about to intersect) and the present (2011).

The Google Ngram is unarguably a way for cryonics organizations to monitor the effectiveness of their literary (cultural) penetration, and if there was any doubt about the decaying position of Alcor, then at least in this regard, the issue is settled by the data in Figure 5, above. It would be fascinating to add to this graph a plot of the respective dollar amounts each organization has spent on public relations and related activities, as well as the respective annual across the board expenditures of both organizations. Of particular interest would be using culturomics to evaluate the effectiveness of public relations firms “image and marketing remakes” on cryonics, such as the costly efforts by WalshCom, Inc., (http://www.walshcom.net/) to recast Alcor’s approach to marketing cryonics to the masses.

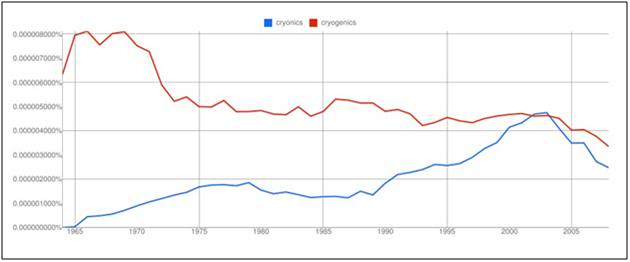

Figure 6: Two terms competing for dominance: the Ngram of cryogenics vs. cryonics from 1965 through 2005.

In Figure 6, it is possible to see how the word cryogenics, which is often conflated with cryonics, “competes” with it over time. While cryogenics is a valid and commonly used scientific term, it is often mistakenly used to denote cryonics. There is clearly a spike in activity in the word cryogenics from 1965 through 1971-72, and this may reflect its increased use during the heyday of the space program in the early to mid-1960s, compounded by the advent of cryonics. The damage done to cryonics by the Chatsworth debacle is of course, reflected in this Ngram, since the gains the word cryonics was making on the word cryogenics are reversed in the early 1980s, at precisely the time Chatsworth’s effects are seen in Figure 4. This kind of “disparate analysis,” showing the same data in juxtaposition to a similar word, cryogenics, provides additional evidence that the negative effect of Chatsworth is real. When I entered “cryonics” and “cryogenics” as Ngram search terms, I had no idea I would see the “suppression” of the word cryonics relative to the word cryogenics, that I observed.

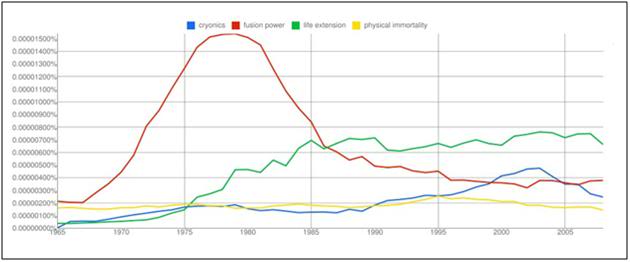

Figure 7: An NGRAM plot of the words cryonics, fusion power, life extension and physical immortality. Fusion power peaked in its cultural domination between ~ 1977 and 1982, after becoming a scientific “darling” in the 1970s, in large measure as a result of the “energy crisis” secondary to the Arab oil embargo of 1973.[19]

Figure 7: An NGRAM plot of the words cryonics, fusion power, life extension and physical immortality. Fusion power peaked in its cultural domination between ~ 1977 and 1982, after becoming a scientific “darling” in the 1970s, in large measure as a result of the “energy crisis” secondary to the Arab oil embargo of 1973.[19]

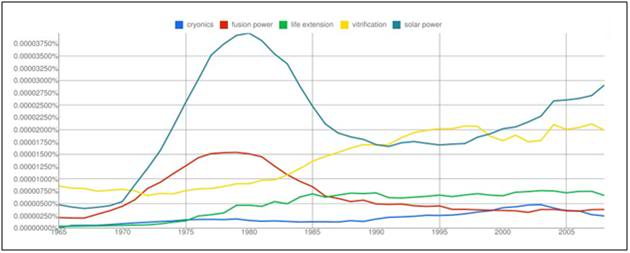

Figure 8: An Ngram plot the same as per Figure 7, above, but with the terms “solar power” and “vitrification” added to the mix. In this case, solar power is making a comeback, following the decline in its cultural penetration after the “energy crisis” resulting from the Arab oil embargo in 1973.[19] Vitrification, which is term that has been in wide used in metallurgy, physics and materials science, begin to experience a marked increase in use after the introduction of the idea of cryobiological vitrification in the mid-1980s.

Ngram plots also allow for comparison between diverse ideas and technologies competing for attention within the culture at any given time. In Figure 8, the terms cryonics, fusion power, life extension, vitrification and solar power are compared. Vitrification is also the term used to described the solidification of metals, water, and other materials absent crystallization in non-biological contexts, and this can be seen as a steady rate of the occurrence of its use from prior to ~ 1965 until the late 1980s. The seminal papers proposing vitrification as an approach to cryopreserving biological systems by Fahy, et al., were published in 1984-86.[20, 21] and several years later the term begins to experience increased frequency of use, a trend which continues through 2005, and likely through the present.

Summary

The continued exponential growth in computing and information handling capacity has led to the ability to manipulate cultural datasets so large that they were previously inaccessible for analysis. This will likely have profound implications for human institutions, both large and small. In the currently tiny sphere of cryonics, this technology seems to offer sufficient precision and sensitivity to allow it to be used as a retrospective tool for evaluating the effect of a range of historical events on the penetration of cryonics (the word and the idea) into the culture. It seems likely that, factoring in the observed lag times for past events until their effect is seen (~2 years), that it may be possible to use this tool prospectively, as well. An interesting and unresolved question will be the possible impact of e-books on shortening the lag time between historical events and the materialization of their consequences in the culture.

References

1. Michel J, Shen, YK, Aiden, AP, Veres, A, Gray, MK. Google-Books-Team, Pickett, JP, Hoiberg, D, Clancy, D, Norvig P, Orwant, J, Pinker, S, Nowak, MA, Aiden, EL.: Quantitative analysis of culture using millions of digitized books. Science 2011, 14(331(6014)):176-182.

2. Ettinger R: The Prospect of Immortality: http://www.cryonics.org/book1.html. New York City: Doubleday; 1964.

3. Kent S: Cryonics Reports 1966, 1(3):4-5.

4. Wainwright L: The cold way to new life: http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=aVYEAAAAMBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_atb#v=onepage&q&f=false. LIFE 1967, 62(4):16.

5. Stanley S, Nelson, RF.: We Froze the First Man: http://cryoeuro.eu:8080/download/attachments/425990/WeFrozeTheFirstMan.pdf. New York City: Dell; 1968.

6. Perry R: Suspension Failures: Lessons from the Early Years: http://www.alcor.org/Library/html/suspensionfailures.html. Cryonics 1992 updated June 2010, 13(2):5-16.

7. CSNY: Proceedings of the First Annual National Cryonics Conference: http://cryoeuro.eu:8080/download/attachments/425990/Proc1stAnn+Cryo+ConfNYC1968.pdf. In: First Annual National Cryonics Conference: 1968; New York City: Cryonics Society of New York; 1968.

8. Allen W: Sleeper. In. USA: United Artists; 1973: 89 min.

9. TransTime: Introduction to Trans Time, Inc: http://www.transtime.com/ttinc.htm. In. San Leandro; 2003.

10. Kunen J, Moneysmith, M.: Reruns Will Keep Sitcom Writer Dick Clair on Ice-indefinitely: http://www.people.com/people/archive/article/0,,20120770,00.html. People Magazine 1989, 32(3).

11. Quaife A: Cryonic Interment Patients Abandoned. The Cryonicist! 1979, October (11).

12. Babwin D: Coroner says lethal dose of drugs killed cryonics case figure. In: The Press Enterprise, Riverside County, CA. Riverside; 1988.

13. Wowk B, Darwin, M.: Cryonics Reaching for Tomorrow. Riverside, CA: Alcor Life Extension Foundation; 1989.

14. Darwin M: Jerry Leaf enters cryonic suspension: http://www.alcor.org/cryonics/cryonics9109.txt Cryonics 1991, 12(9):19-25.

15. CryoCare: http://www.cryocare.org/index.cgi

16. Best B: A history of cryonics: http://www.benbest.com/cryonics/history.html. In. Detroit: Ben Best; 2006.

17. Hancock D: Ted Williams Frozen In Two Pieces, Meant To Be Frozen In Time; Head Decapitated, Cracked, DNA Missing – CBS News: http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2002/12/20/national/main533849.shtml. In: CBS News. New York: CBS News, New York City; 2003.

18. Johnson L, Baldyga , S. : Frozen: My Journey into the World of Cryonics, Deception, and Death, vol. : Vanguard Press 2009.

19. Barsky R, Kilian, L.: Oil and the Macroeconomy Since the 1970s: http://www.sais-jhu.edu/bin/u/r/R_Oil_and_the_Macroeconomy.pdf. Journal of Economic Perspectives 2004, 18(4):115-134.

20. Fahy G, MacFarlane, DR, Angell, CA, Meryman, HT.: Vitrification as an approach to cryopreservation. . Cryobiology 1984, 21(4):407-426.

21. Fahy G: Vitrification: A new approach to organ cryopreservation. Prog Clin Biol Res 1986, 224:305-335.

[1] Without question, one of the most urgent priorities is to digitize newspapers and their “morgues;” the huge reservoirs of photographs, cuttings and source materials that newspaper keep on hand as resource and research material (and which have virtually proprietary or “secret” status). The demise of the newspaper and magazine industries is leading to massive and irretrievable losses in both the original newspapers themselves, as well as in the loss of morgue material, as failing newspapers can no longer afford the overhead of storage, and send this material to the dustbin.

I had a bad feeling about the Ted Williams affair from the beginning. One, it looks as if Alcor bent or broke its own rules in the gamble of cryosuspending a celebrity. Two, I haven’t seen unambiguous evidence that Williams wanted cryonics for himself. Three, the children from Williams’s two marriages brought their dispute about his wishes for the disposition of his body into public view. Four, Williams’s son already had a bad reputation among sports writers who cover baseball, so they tended to side with the cryonics-hostile daughter. And five, people who idolize sports figures tend to fall into the lower end of the IQ curve, making them unreceptive to cryonics’ reasoning any way.

Mark, the points you make, and the questions you indirectly raise, merit a whole article. When I was first introduced to John Henry Williams, I had no idea who he or his father were. Not surprisingly, I have never had any interest in competitive sports, and truth to tell, I am still in the process of understanding who Ted Williams was. I got a bit of a feel for who Ted Williams the man was when I turned on the TV in the “business hotel,” wherever they had parked me in Scottsdale/Phoenix, the day after his cryopreservation. The TV had been tuned to a sports channel by the previous guest, and of course, the announcement that Williams had died was big news. Whatever this channel was, it did nothing but run back-to-back episodes of a fishing travelogue program Williams did some years before. One of the episodes was in Russia and, as much as it was about fishing, it was also about Williams’ views on life and philosophy. I remember thinking, “People must really dislike this guy.” He was very blunt, opinionated, and made no bones about not only being an atheist, but about not thinking much of the cognitive capacity of people who weren’t. I was bone tired, and I just lay there with my eyes mostly closed and listened, but my impression was that the program had been made before the fall of the Soviet Union. Very recently, in trying to understand the Ngram plots of his celebrity, I’ve had to get a better understanding of his influence on the culture. Williams was a very unusual sportsman and his approach to sport was pretty much antithetical to that of the time in which he lived. I haven’t read his autobiography, but I have looked over his 1970 book, The Science of Hitting (or more properly the 1986 revision). If he hadn’t been a baseball player, he would have made a fine scientist, or an engineer. If you a do a plot of articles about Williams in the New York Times, and then you look at those articles, you get an idea of why his Ngram curve is shaped as it is. He was a very, very unusual and contrary man. He was also very lucky the world never really understood him. His career was huge triumph of fame over personality.

The cryonics issues need to treated elsewhere, as I said before. — Mike Darwin

I grew up with the same lack of interest in sports (it was out and out hatred for years, but I mellowed), and the first I ever knew about Ted Williams was that he was a cryopreserved celebrity.

.406

The most significant fact about Ted Williams.

Since I’m not a MLB fan, I also did not know who Ted Williams was until his cryo-suspension.

Awesome, Abelard; I knew you were my kind of person. :)

I had to look up .406 just now to find out what it meant, though I did guess correctly without help.

Of course, I also find this fact about Ted Williams significant: -196C.

Jimmy Stewart plays a character based on Ted Williams in the film “Strategic Air Command” (1955), about a professional baseball player and World War II veteran recalled to duty in the U.S. Air Force.

Another interesting fact: Williams had franchised his name to Sears-brand sporting goods in the 1960′s. A couple years ago I handled a used .30-30 Winchester rifle for sale in a gun shop which had Williams’s signature engraved on the barrel. The original owner had apparently bought it from Sears decades ago.

Actually, I first learned of the “.406″ batting average from a movie – “Righteous Kill” – featuring Robert De Niro and Al Pacino, who play two NYPD detectives trying to catch a serial killer. At one point in the movie, Al Pacino says “406 captain, 406″, then preceded to explain it to the captain.