Question: How did God create heaven and earth?

Question: How did God create heaven and earth?

Answer: God created heaven and earth from nothing by His word only; that is, by a single act of His all-powerful will.

Question: Why did God make you?

Answer: God made me to know Him, to love Him, and to serve Him in this world, and to be happy with Him forever in heaven.

– Baltimore Catechism, Revised Edition (1941)

By Mike Darwin

No.

If this universe we inhabit was created by an intelligenc(s), then it was not in that way, and not for those reasons. I think I know what one of those reasons might really be.

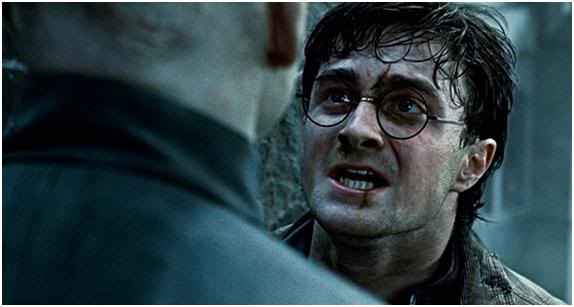

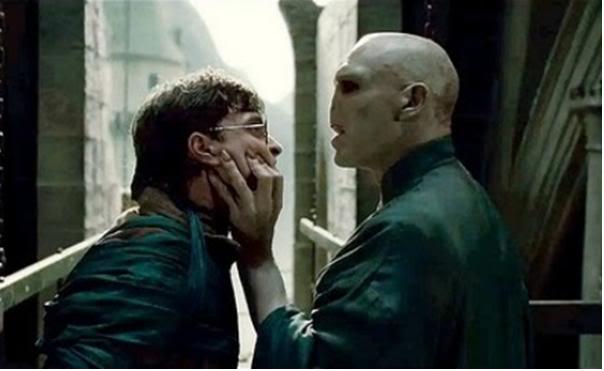

Early this morning I saw Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2 (2011) in one of its opening release showings in state-of-the-art digital video and surround sound. It is a gorgeous work of art – a successful assault on the pinnacle of what is now possible cinematically. The imagery and mood of the film are evocative of those in the recently published and surreally beautiful book, Beauty in Decay: The Art of Urban Exploration by RomanyWG (Gingko Press, July 15, 2010, ISBN-10: 1584234202).

The resolution of the images, both real and computer generated (CGI), is superb and unassailable. The credibility of CGI has surpassed that of what is possible when merely capturing reality on film, and by this I mean that the unreal trumps the real and the unbelievable is more credible than the believable. Sitting there dazzled by the sheer beauty of the film’s imagery, it occurred to me why god(s), if there are any, made the universe – because they could realize a place vastly more beautiful and wonderful, and vastly more terrible and dark than the world which they themselves are confined to.

The resolution of the images, both real and computer generated (CGI), is superb and unassailable. The credibility of CGI has surpassed that of what is possible when merely capturing reality on film, and by this I mean that the unreal trumps the real and the unbelievable is more credible than the believable. Sitting there dazzled by the sheer beauty of the film’s imagery, it occurred to me why god(s), if there are any, made the universe – because they could realize a place vastly more beautiful and wonderful, and vastly more terrible and dark than the world which they themselves are confined to.

This film is, of course, only the barest and the most basic realization of that possibility. It represents the best efforts of a species with only sub-picoscopic knowledge of their universe to imagine a credibly different one. And it is for just that reason that this film is so amazing. The imagined living systems brought to life before the viewer reflect an understanding, rendered into equations and countless lines of code, of some of the fundamental principles of how biological things move and flex and interact in our world – of how they actually behave on a macroscopic level.

The labored respiratory movements of captive, half-blind dragon, and the animation of the creatures that populate the film are not just flawless, they are beyond that, because if you realize that these movements cannot be simply scaled up or down from some simple model, you then begin to realize some of the technical magnificence of the film. The CGI programmers are beginning to render their worlds from first principles, and armed with those, they are creating brand new worlds that are more credible and more real than any in our former imaginings. Artists can draw and paint, but the texture of their fantasies always falls short of truly achieving reality, let alone exceeding it. This film shows us the barest beginnings of what that excess is likely to hold, and it is at once exhilarating, and deeply disturbing. I looked at the unfolding of this “film,” a misnomer now, for it is far, far removed from the technology of unruly chemical reactions on a plastic membrane, and I was struck by the thought, “I can see now that we will soon be able to imagine not only much nicer places than we inhabit, but places that will be much realer, and more compelling too.”

By “nicer” I do not necessarily mean more “pleasant.” There are physical limits imposed by our universe on how much pain, how much suffering, how much physical distortion, disruption and rending of the flesh are possible, before life ceases. It is the sorrow of every sadist and every masochist that the flesh of the body can only be tortured in so few, and so finite ways. What are the implications of that? Perhaps it would be wise for us to reflect on the quote from Milton’s Paradise Lost, “The mind is its own place, and in itself can make a Heaven of Hell, a Hell of Heaven.” And perhaps as well on a quote from the film itself, when Harry Potter asks about a postmortem experience he is having, “Is this just happening in my head, or is it real?” to which Dumbledore replies with alacrity, “What makes you think that just because it is happening in your head it is not real?”

By “nicer” I do not necessarily mean more “pleasant.” There are physical limits imposed by our universe on how much pain, how much suffering, how much physical distortion, disruption and rending of the flesh are possible, before life ceases. It is the sorrow of every sadist and every masochist that the flesh of the body can only be tortured in so few, and so finite ways. What are the implications of that? Perhaps it would be wise for us to reflect on the quote from Milton’s Paradise Lost, “The mind is its own place, and in itself can make a Heaven of Hell, a Hell of Heaven.” And perhaps as well on a quote from the film itself, when Harry Potter asks about a postmortem experience he is having, “Is this just happening in my head, or is it real?” to which Dumbledore replies with alacrity, “What makes you think that just because it is happening in your head it is not real?”

The story line of the film captures with perfection the essential values of this culture. The “final” battle between good and evil is played out; Lord Voldemort, whom the author of the Harry Potter books has described as “a raging psychopath, devoid of the normal human responses to other people’s suffering,” is bent upon removing the last obstacle to his immortal existence and his ongoing journey to conquer his world. And that obstacle is the boyishly genteel Harry Potter. Now a man – emotionally, physically, and intellectually mature, Potter is repeatedly confronted in the film with the choice to grasp ultimate power, or to suffer and die. He chooses the latter, not once, but twice (Rowlings trumps Christianity, there). As the film ends, he finds himself holding “The Elder Wand” and realizes that it will grant him supreme power: his response is to break it in two and cast the pieces away.

The story line of the film captures with perfection the essential values of this culture. The “final” battle between good and evil is played out; Lord Voldemort, whom the author of the Harry Potter books has described as “a raging psychopath, devoid of the normal human responses to other people’s suffering,” is bent upon removing the last obstacle to his immortal existence and his ongoing journey to conquer his world. And that obstacle is the boyishly genteel Harry Potter. Now a man – emotionally, physically, and intellectually mature, Potter is repeatedly confronted in the film with the choice to grasp ultimate power, or to suffer and die. He chooses the latter, not once, but twice (Rowlings trumps Christianity, there). As the film ends, he finds himself holding “The Elder Wand” and realizes that it will grant him supreme power: his response is to break it in two and cast the pieces away.

The closing sequence of the film is of Harry Potter and his cohorts as mature men and women living in the everyday world we all inhabit. He has a child now, and it is time to send him off to Hogwarts boarding school to learn the craft of Wizardry. Age has begun to mark Harry Potter, and these scenes are meant to show us that by his deeds, he has ensured and acceded to the triumph of generational mortality. Harry Potter will grow old and die, as will his children, and his children’s children. Immortality is not for men, nor is super-knowledge beyond that already granted to Wizards, which is, of course, vastly greater than that granted to the mere “muggles” whose world they cohabit.

The closing sequence of the film is of Harry Potter and his cohorts as mature men and women living in the everyday world we all inhabit. He has a child now, and it is time to send him off to Hogwarts boarding school to learn the craft of Wizardry. Age has begun to mark Harry Potter, and these scenes are meant to show us that by his deeds, he has ensured and acceded to the triumph of generational mortality. Harry Potter will grow old and die, as will his children, and his children’s children. Immortality is not for men, nor is super-knowledge beyond that already granted to Wizards, which is, of course, vastly greater than that granted to the mere “muggles” whose world they cohabit.

The word hallows means to honor as holy, to make holy, or to consecrate. “Deathly Hallows” indeed – the perfect title for this beautifully made and imagined film, with a poisonous message as old as Christianity, or or the denouement of the Epic of Gilgamesh.

I’ve studiously avoided the whole Harry Potter thing, except to marvel at how children could persuade their parents to stand in line at chain bookstores at midnight to buy the next phone book-sized volumes in this series, which has translated into getting their parents to stand in long lines with them at movie theaters.

I also find it interesting that Rowling has stumbled on a myth which has obsessed a whole generation of children not noted for its literacy and attention span in other ways. Indeed, many children have defied their parents’ prohibitions to learn everything they can about this fictional world, especially the Potter obsessives in christian fundamentalist families. If we could just figure out how to introduce something like Harry Potter to the Muslim world, it might interfere with Islamic indoctrination (because of the zero-sum nature of time management) and make the next generation in those dysfunctional countries less religion-crazed.

I’ve tried to avoid exposure to the Twilight fad as well, but unfortunately until about a year ago I worked with a young woman, again not particularly literate, who had read all four of Stephenie Meyers’s novels, then had to tell me more than I cared to know about them. Apparently in the fourth novel, the heroine Bella Swan plays a “reverse Arwen” by choosing to become a vampire so that she can she can live youthfully forever in the standard-issue vampire superhero body with her vampire husband. This seems to turn the usual trope about the beauty of abnegation and self-sacrifice unto death on its head – or perhaps we’ve had the trope upside-down all along, and Meyer in her clumsy way has tried to orient it properly.

I’m not a Harry Potter fan at all, and I’ve read none of Rowlings books. No active aversion here, just not to my tastes. I have, however, seen all of the films, but one, because my partner likes them. We saw the first one with friends some years ago, and mt partner, sometimes with friends, sometimes not, has seen all the subsequent ones. A relationship is a give and take, and so I’ve gone with him to all of them, with the exception of the one prior to this one. They are all well crafted and can only be described visually complex and imaginative. The story line has never much appealed to me, and I think one reason my partner likes them is that he was raised on the C. S. Lewis CHRONICLES OF NARNIA stories as part of his religious education. I will say that in England, the Potter books are ubiquitous and you find them in the homes of the elitite and the plebian; read by intellectuals and the barely literate alike. In general, ANY books that get people to read who would otherwise not do so are good thing – even if they are ideologically poisonous. Get a man to read and you’ve given him a chance at expanding his world dramatically, and often for the better.

This last film of the Harry Potter series is different than the rest that I have seen in that its technical execution and artistic vision have transcended any genre. You may not appreciate the artisic atmosphere if you don’t find Urbex landscapes, like those in BEAUTY IN DECAY appealing. However, I think any objective viewer would be hard pressed not to appreciate the unbelieveable technical realism – supra-realism, in fact – with which the film is executed. It is possible for me, and I think for many others, to see technical mastery so vast, and to be in awe of it, even if it is being used to materialize a world we are not enamored of. I must have spent a good portion of the film imagining how those tools could be used at my command to create my imagined worlds – and the results were very satisfying. I’ve not seen anyof the TWILIGHT or the HBO TRUE BLOOD films. The latter have come highly recommended by a broad cross sectioon of friends, and I very much liked Alan Ball’s SIX FEET UNDER series. In fact, I own it on DVD.

One final word; don’t keep yourself too cloistered, or otherwise isolated,even from a psychopathic culture. Diversity in stimulation is essential to intellectual and psychological health and one of the things that it teaches you is that there are excellent, and often powerful tools to learn about, even in the hands of, and when develped by moral bankrupts and monsters. By interacting with a vast range of people, I’ve learned that ther are very valuable and powerful things to be learned almost everwhere you look. The most debauched human being often has as much or more to teach about the nature of life and being as the most venerated saint – and sometimes, I think, quite a lot more. If you are not familiar with the works of Leni Refienstahl, she is a classic case in point. She developed and entire new genre in film and her artistic sense is one that has not only endured, but come to thoroughly permeate the culture. — Mike Darwin

Speaking of vampires, I find it interesting that they’ve gotten a public-relations makeover in the culture over the past couple of generations, while Victor Frankenstein still has a bad reputation.

After all, vampires live the American dream: They don’t age, and many of them look physically attractive; they display superior stamina and recuperative powers so that they can party every night and not suffer for it; they don’t have to save for disability, health care and old age, so with their simplified needs they can build up wealth for decades and centuries and therefore have the resources to live lavishly when they choose to; they have the opportunity to become super-sophisticated and adept at influence and seduction; etc.

Poor Victor, by contrast, reminds people of the geeky kid you knew in middle school who watched Star Trek, played Dungeons & Dragons and read books by Carl Sagan. Therefore he lacks status and respect in mainstream culture.

Yet the Victor types generate the ideas which can lead to scientific and medical breakthroughs and new high-tech industries; in Victor’s case, he thought way ahead of his time by attempting to conquer death itself. If some people fantasize about becoming vampires because vampires don’t age and can live a really, really long time, then why can’t they see that Victor Frankenstein shows them a way to that end which might have a basis in reality, namely through science? I’d like to see the era when we want to compliment someone by calling him a “Frankenstein,” because if we survive to the kind of “future” we want, we will all have become the beneficiaries of the Frankenstein myth, properly reinterpreted.

You should blog this, Mark.

“Sitting there dazzled by the sheer beauty of the film’s imagery, it occurred to me why god(s), if there are any, made the universe – because they could realize a place vastly more beautiful and wonderful, and vastly more terrible and dark than the world which they themselves are confined to.”

It’s not often that I hear a new and interesting idea in teleology, and that is one.

It’s not often that I think of any. — Mike Darwin