By Mike Darwin

A Brief History of Attempts to Create and Implement Minimum Standards in Cryonics

A Brief History of Attempts to Create and Implement Minimum Standards in Cryonics

INTRODUCTION

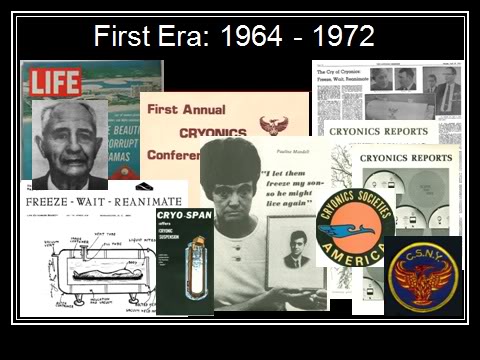

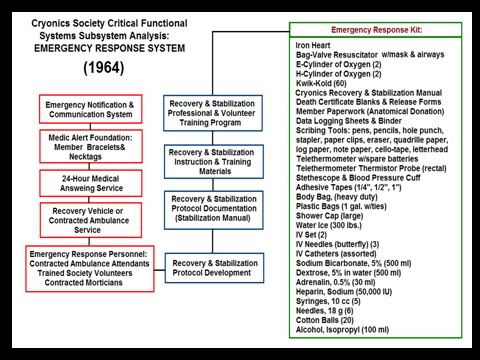

First Era 1964-1972

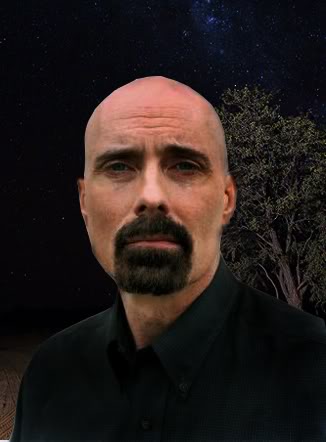

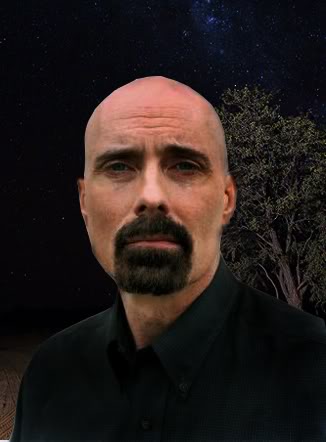

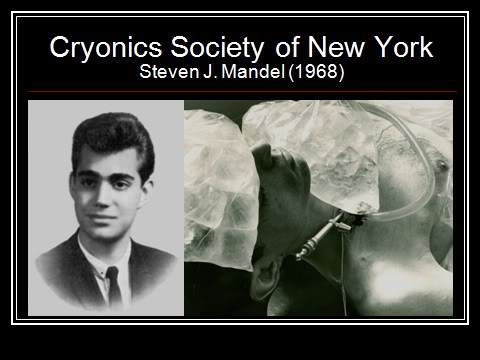

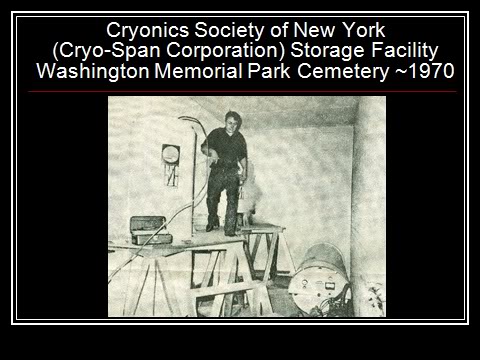

The first attempt to create formal minimum standards for cryonics organizations in the form of the Cryonics Societies of America (CSA) was initiated by in 1968 and was implemented largely through the efforts of the Cryonics Society of New York. The CSA was to be a national standards and enforcement organization, comprised of representatives elected by the individual, member cryonics societies.

Figure 1: Requirements for membership in the Cryonics Societies of America.

Creation of the CSA, and the terms of its incorporation were agreed to by the Officers/Directors of the then extant cryonics organizations: Cryonics Society of New York (CSNY), Cryonics Society of Michigan (CSM) and Cryonics Society of California (CSC). CSA was incorporated late in 1969.

The CSA called for basic accountability in matters such as public communications, information inquiries, membership rolls, financial and member/patient record keeping (submission of quarterly financial records), documentation of cryopreservations (including at least one “confidential” photo), uniformity of letterhead and logos, submission of regular progress reports and investigation of all persons or corporations offering cryonics services or promoting cryonics. Basic requirements were maintenance of a phone and book listing under the heading “cryonics”, updated list of Officers & Directors, valid addresses for organization and Officers, and subscription to “Cryonics Reports” for all local group members and a complete log of all written and telephonic information inquiries.

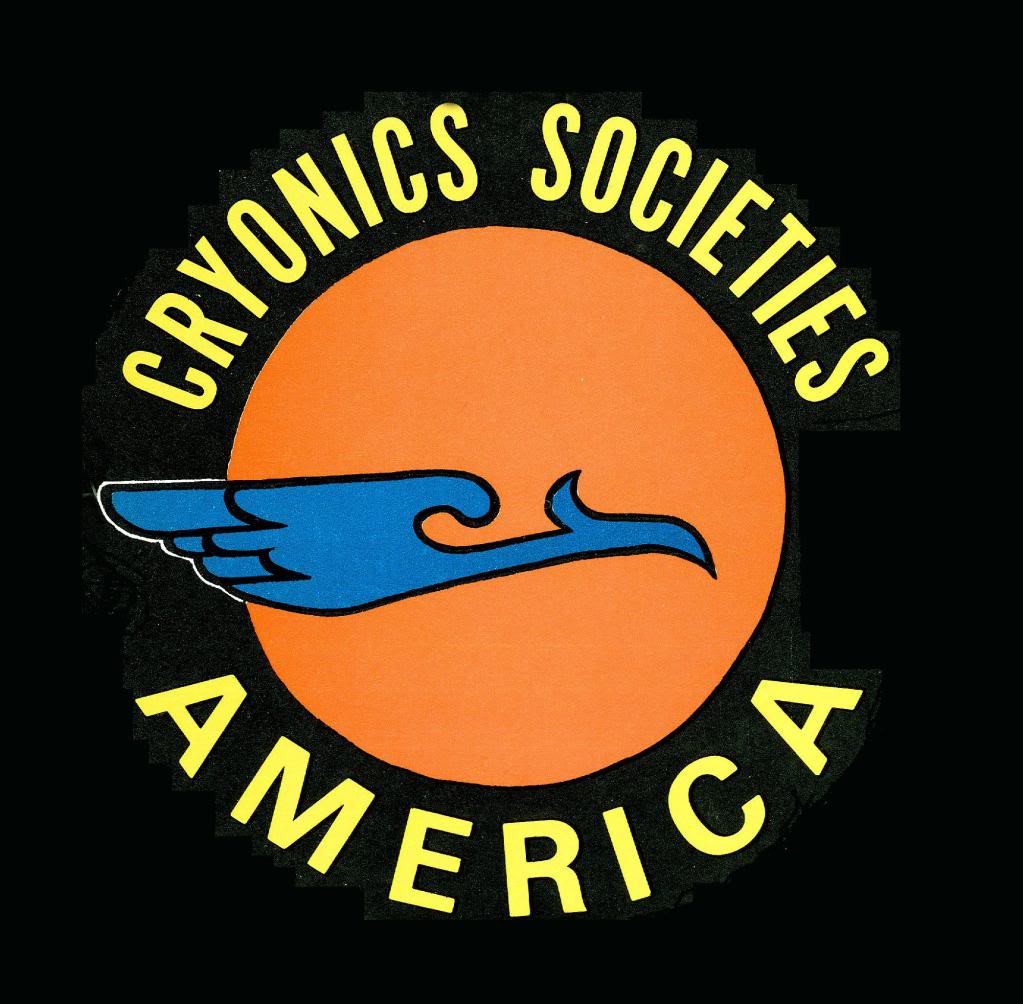

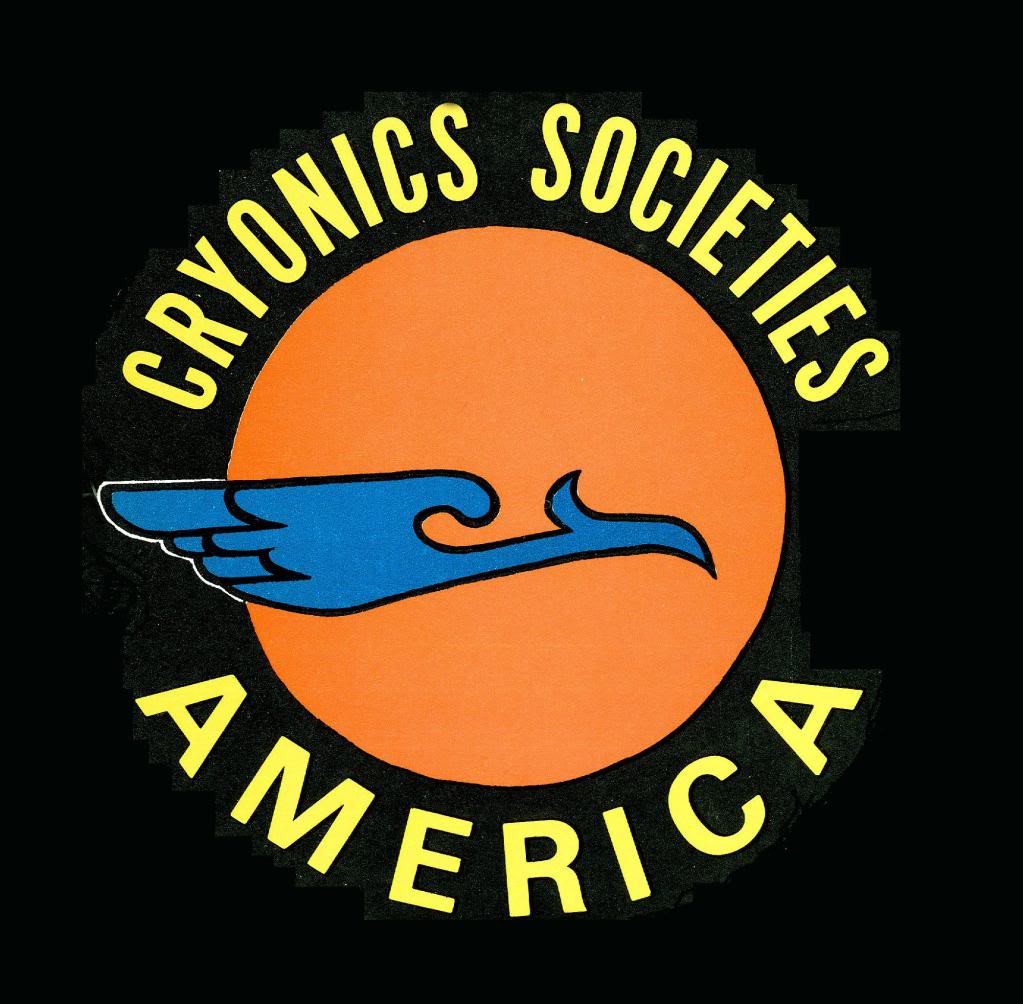

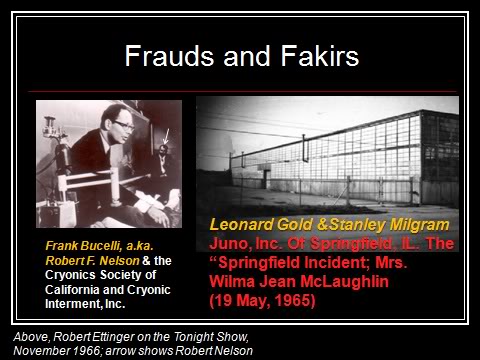

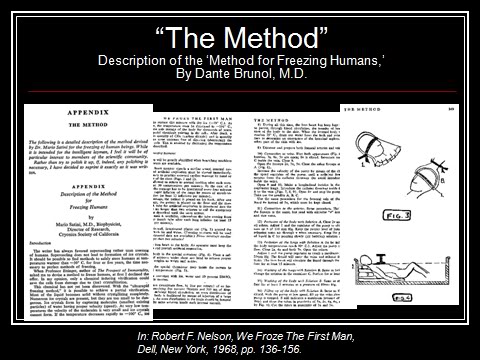

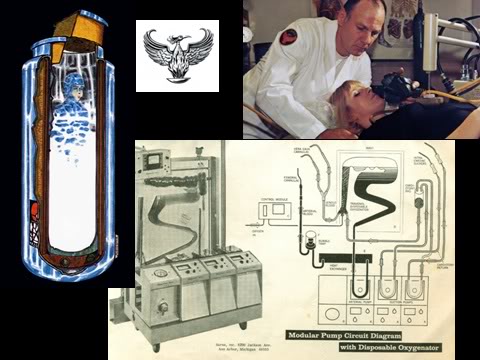

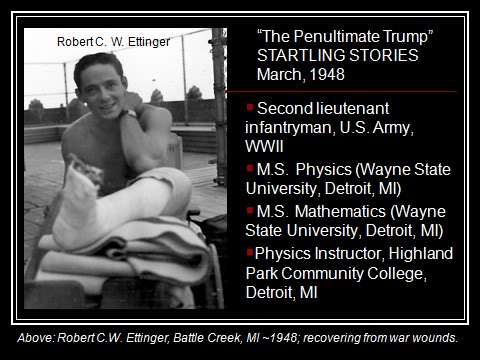

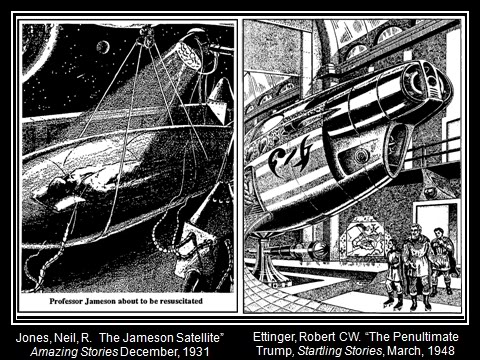

Ironically, one of the driving forces behind CSA was Robert Nelson who, in particular, wanted a standardized procedure generated to administer cryopreservation, particularly with respect to perfusion. A committee consisting of Ettinger, Nelson and Saul Kent was created in April of 1968 to do this, however, according to Kent and Henderson, there was no progress on this, the committee never met, and Nelson did not answer correspondence nor generate the promised liaison with Dante Brunol, M.D., and the CSC mortician Jeff Hicks. Despite misgivings, CSNY committed to be the central body and administration for CSA, and the artist Vaugn Bode generated a logo. Letterhead for national organization was created and standards for regional letterheads were created and implemented.

Figure 2: Vaughn Bode’s CSA logo of a side-view of a Phoenix in flight.

Figure 2: Vaughn Bode’s CSA logo of a side-view of a Phoenix in flight.

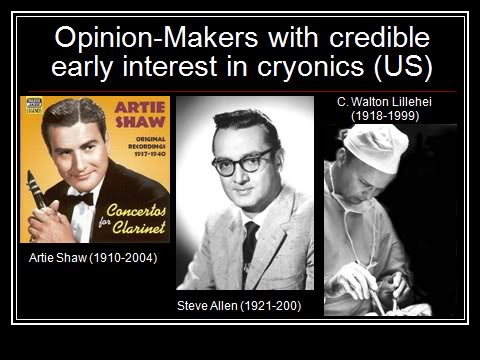

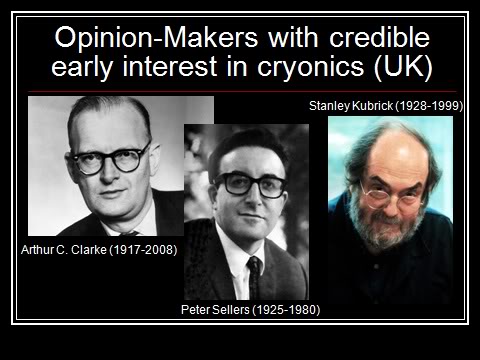

Another critical function of the CSA, and the one which may have motivated its initiation, was the creation of a Scientific Advisory Council (SAC) to the CSA. This Board was to have provided scientific and technical advice related to patient care, evaluated research proposals and recommended funding, and lastly and most importantly, serve to improve the public and professional credibility of cryonics. By 1968, resistance in the scientific community at large was hardening and the cryobiological community was well on its way to becoming highly polarized against cryonics. By this time the mother of cryobiology, Audrey Smith, had already made her public statement calling Ettinger “that horrible man” and Robert W. Prehoda was writing his virulently anti-cryonics book chapters in Suspended Animation: “The Night of January 12, 1967 and “The Lunatic Fringe.” There is some indication that Saul Kent, and perhaps others, may have either seen a precis of these chapters, or otherwise been appraised of their tone, if not their content (CSNY Correspondence Log, 1968).

Figure 2: The 28 April, 1969 letter from Saul Kent laying out the basic parameters required for a national cryonics standards organization to operate.

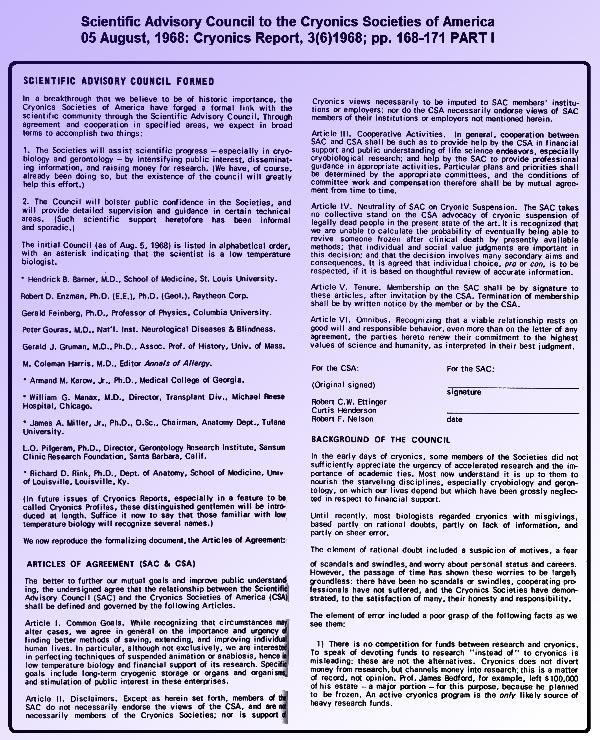

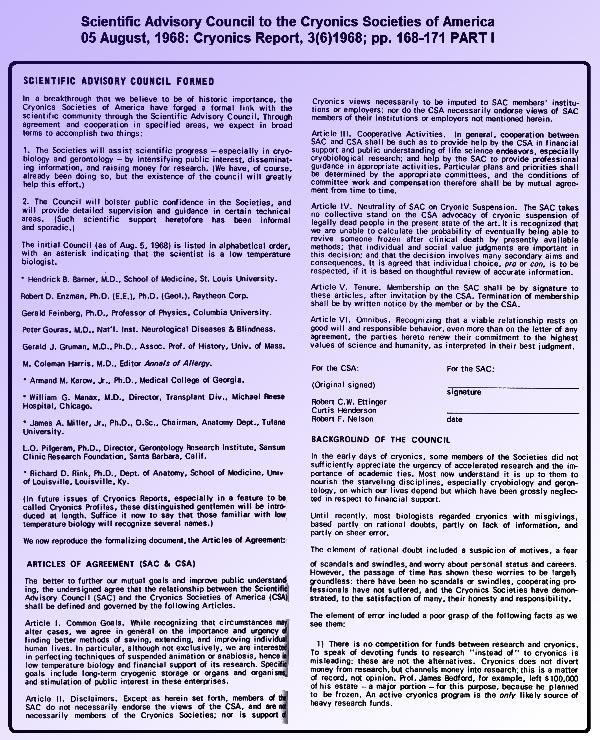

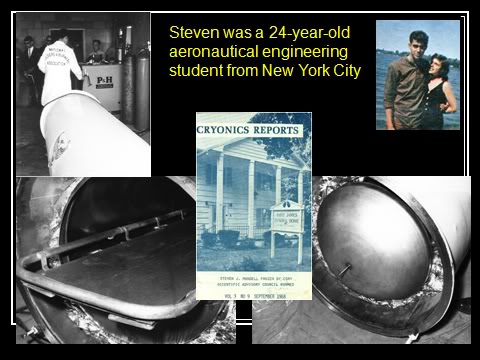

The SAC was formed on 05 August, 1968 and the relevant documents as well as its composition were published in Cryonics Reports in September, 1968:

Figure 3: The charter of the Scientific Advisory Council (SAC) to the Cryonics Societies of America (CSA). The SAC was to provide the scientific oversight and vetting that would be needed to determine which cryopreservation procedures were applied clinically, and to help direct research to improve them.

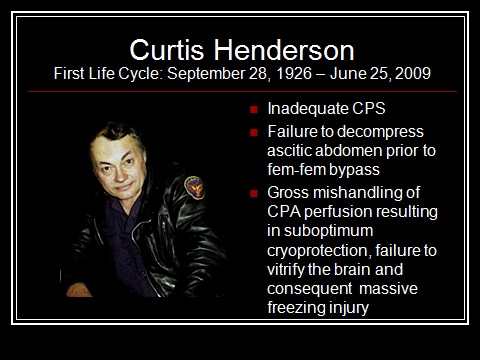

There is little known surviving historical documentation of the activities of SAC. According to both Saul Kent and Curtis Henderson, the SAC was not very active and not very responsive to requests for help, although, as they both noted, the areas in which help were most urgently needed either required speculation and expertise (expert speculation from a cryonics perspective, as it were) that the SAC scientists did not have (e.g., formulating perfusion, cooling and storage protocols) or required resources neither the CSA nor its member organizations had available (financing for research). It is clear from correspondence and conversations with some of the principals (Henderson, Kent, Barner and Gouras) that the major obstacle to the SAC’s long term viability was the inability of the CSA to provide anticipated funds for research to be generated by the CSA. There is no evidence that the CSA, acting as unit, provided any input or material support, scientific or technical. The list of the SAC members was used extensively to lend credibility to cryonics for promotional purposes and the list was reprinted as a full page of Cryonics Reports magazine until the SAC gradually disintegrated due to members resigning.

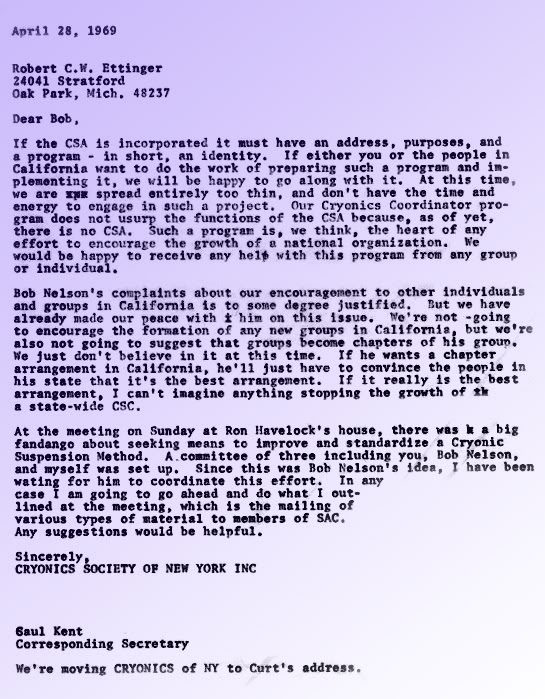

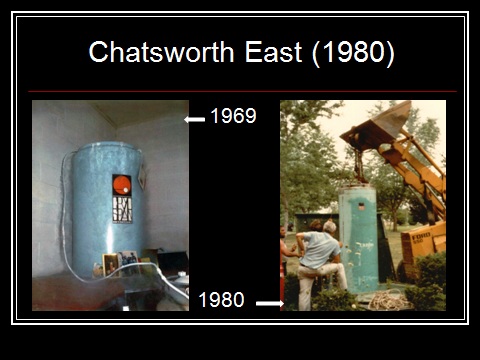

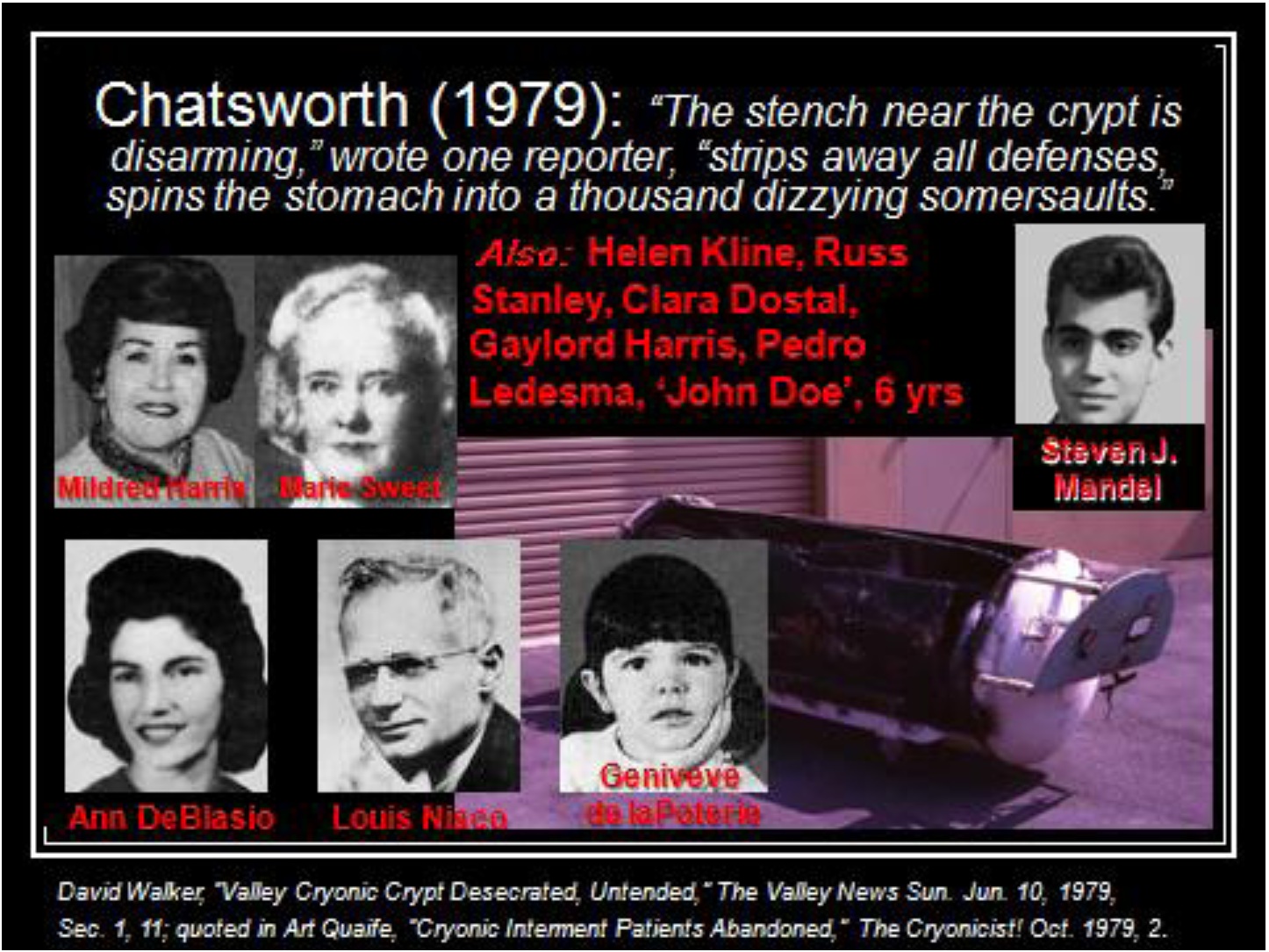

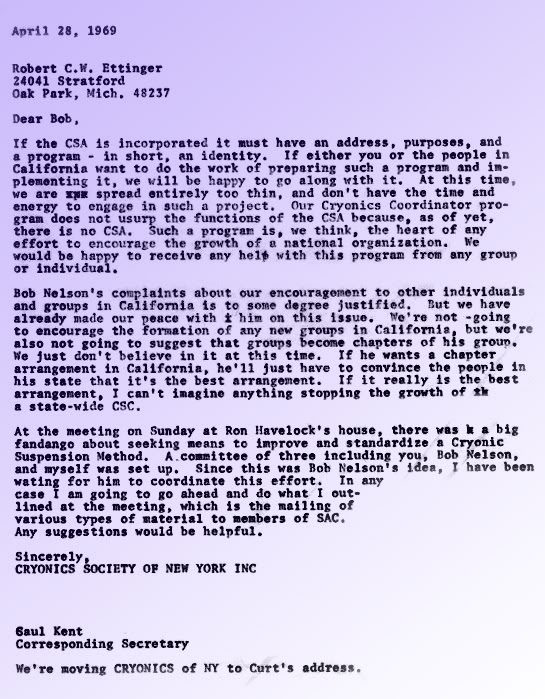

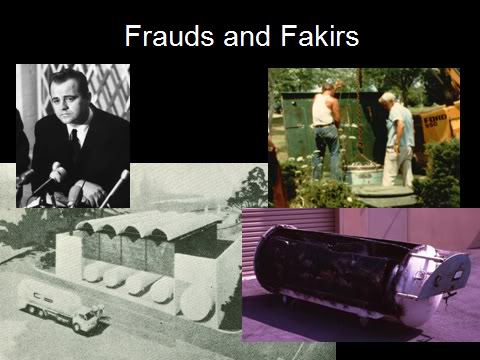

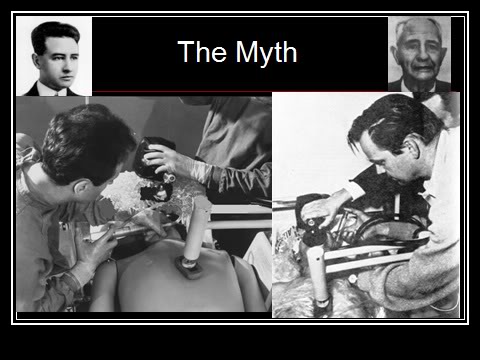

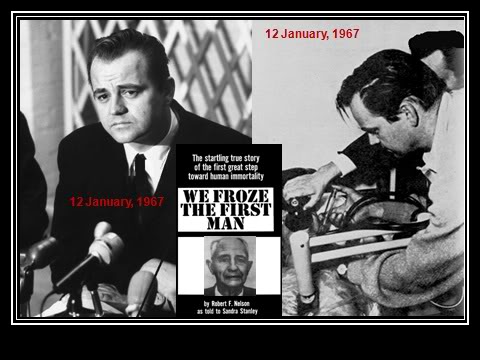

The CSA did remain modestly active for perhaps a year after its inception. There is documentation of essentially complete compliance with the CSA’s requirements in the archival files of CSNY, and much of this material survives and is being digitized. There is evidence that CSM provided substantial compliance, including providing membership rolls, records of information requests, and at least semi-annual bookkeeping summaries. CSC did not provide membership lists, patient records, or financial data. They did provide photographic evidence of the cryopreservation of Marie Phelps Sweet, under substantial pressure and amid allegations (untrue as it turned out) that Ms. Sweet‘s cryopreservation may have been a hoax used to raise money for CSC or Robert Nelson, and those photographs have survived and been digitized.

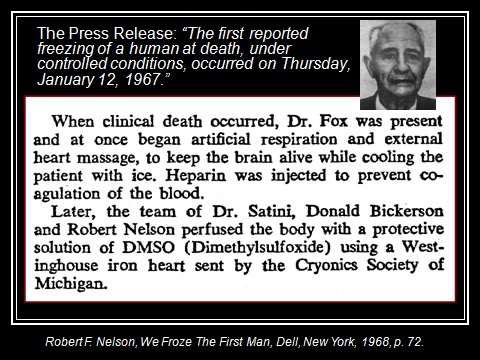

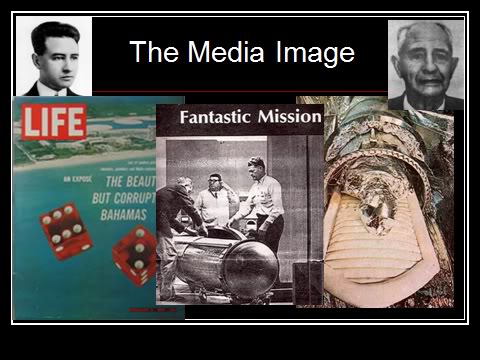

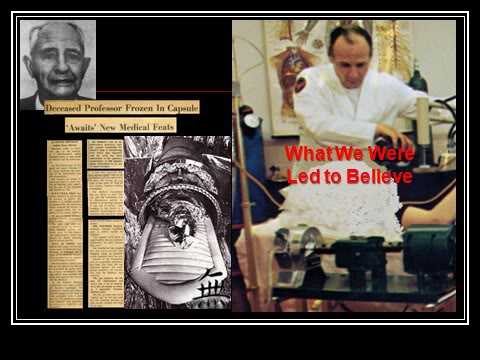

Figure 4: Robert F. Nelson, President of the Cryonics Society of California

Figure 4: Robert F. Nelson, President of the Cryonics Society of California

While the CSA was neither very active nor effective, it did continue to exist, at least in name, until serious concerns about the operations of CSC, Cryonic Interment and the integrity of Robert F. Nelson were raised, and finally aired publicly by Saul Kent in an editorial in Cryonics Reports entitled “Trouble in Southern California?” which questioned the integrity of CSC’s patient storage operations (Cryonics Reports: 4(12) 1969; p 2) as noted in this quote from that article:

“At last years’ national cryonics conference in Ann Arbor, Mich. [actually held in April 1969, 8 months before--MP], and Marshall Neel’s presentation concerned a new cryonic storage facility which, according to Mr. Neel, was close to completion. Slides showing the process of construction were offered, and it was stated that within a short time there would be a grand opening before the media, at which several bodies then in individual cryonic storage would be placed into a large multiple-body unit. Cryonic Interment Inc. was the name of the company that was said to own the facility; Mr. Neel was announced as President.

Since the conference there have been continual statements emanating from the leadership of the Los Angeles based company about the imminence of the opening of the facility.

As of December, 1969, the facility has not been opened and there is no evidence to indicate that it will.

We don’t know what has been going on in Southern California because the entire operation has been veiled in secrecy. It is just this air of secrecy that troubles us.”

The CSA probably became legally defunct within a year or so thereafter since there are unpaid bills for corporation taxes and no evidence of disbursements for these from, either the CSNY or CSC financial archives which are complete for this period. Unless the fees were paid by CSM or by an individual(s) the CSA would have legally ceased to exist sometime in 1970.

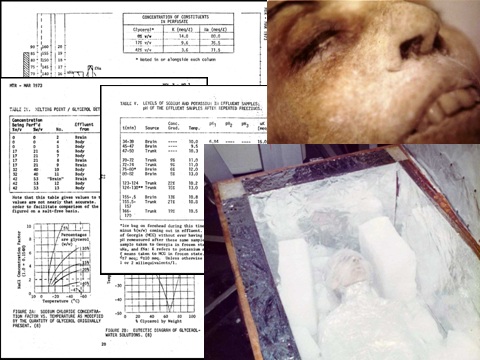

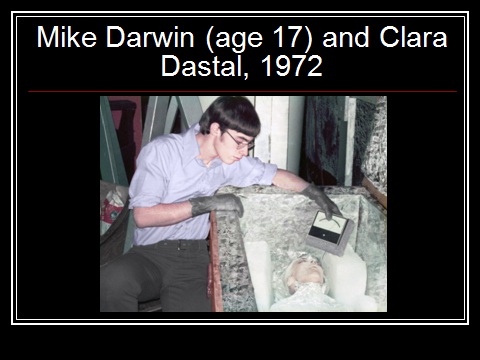

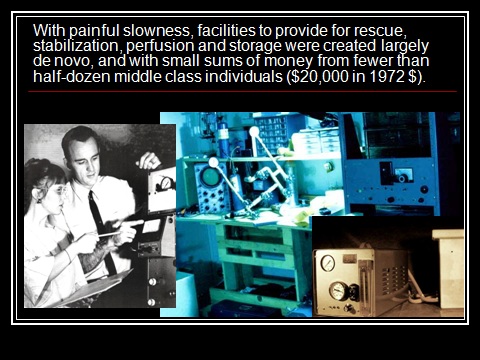

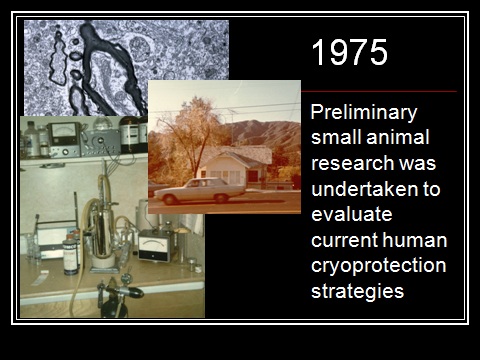

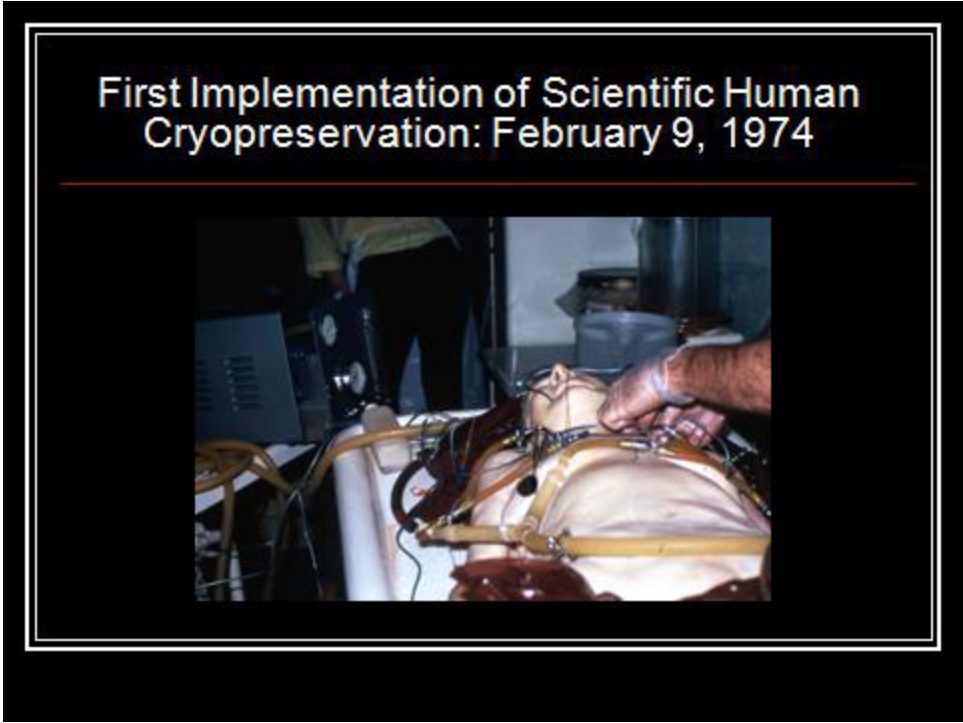

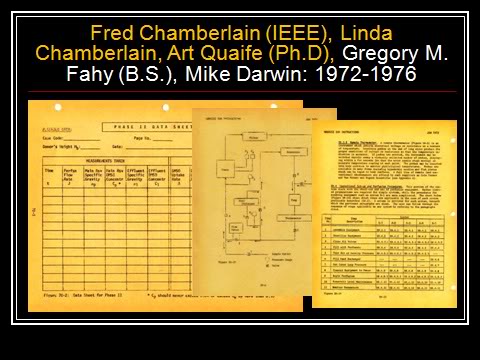

Second Era 1972-1976

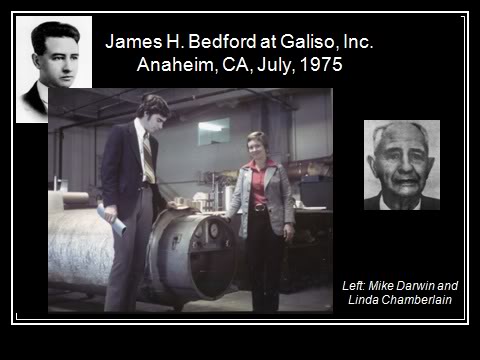

Figure 5: Fred and Linda Chamberlain began a second round of unsuccessful efforts in the early 1970s to create a minimum standards and compliance self- regulatory framework for cryonics. This effort, as had the previous one in the form of the CSA, proved unsuccessful.

The next attempt to establish industry-wide binding standards was initiated by Fred and Linda Chamberlain of the Alcor Foundation in 1972. The effort had, if I recall correctly, the acronym DOMSAC which stood for ” Document of Minimum Standards and Compliance” (DOMSAC). The core requirement of the DOMSAC were to:

“Set minimum standards for all technical aspects of perfusion and cool-down, including data collection formats, parameters to be logged, frequency of data acquisition, minimum equipment and chemical to kept on hand at all times, and so on.” The objectives of the DOMSAC were to:

- Established a basic standard for organization, reporting and public disclosure of patient case data.

- Required continuous public accountability (address, identification, a.k.a. and d.b.a. history on all Officers and Directors).

- Established minimum requirements for emergency notification and communication systems.

- Limited the scope and nature of claims that could be made to the public or prospective members/clients about cryonics.

- Impose substantial administrative requirements, as well as mechanics for handling non-compliance and provisions for punitive measures if necessary.

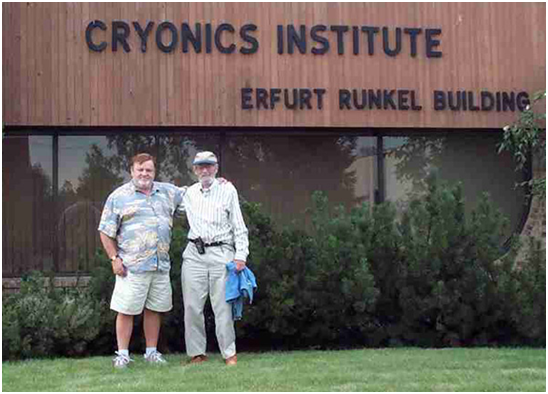

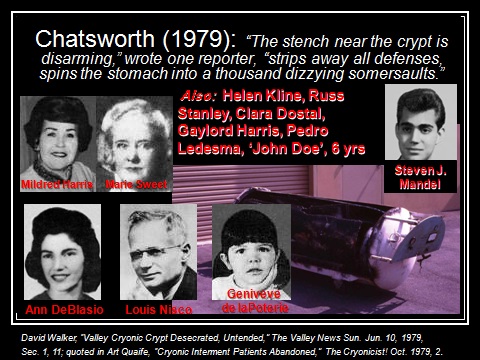

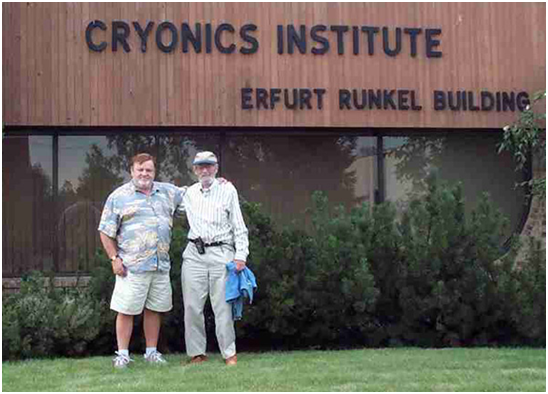

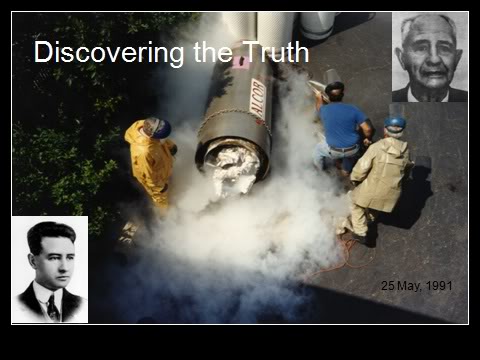

Figure 6: Former President of the Cryonics Society of California, Robert F. Nelson (aka Frank Bucelli) being warmly received by Robert C. W. Ettinger, one of the two originators of the cryonics movement in 20

This document provoked extended haggling and arguments from Trans Time (TT) and the Bay Area Cryonics Society (BACS). (BACS and TT were essentially run by the same management at that time), and to a lesser extent from the Cryonics Society of Michigan (CSM). The was concern expressed on the part of TT/BACS that the DOMSAC constituted an unacceptable step towards the surrender of autonomy, even if it was in the form of mutual oversight.” To what extent these sentiments were justified it is impossible to know. It certainly has been the case that getting cryonicists, even within their own organizations, to submit to oversight and regulation has so far proven impossible. For instance, Robert F. Nelson was in no way punished for his misdeeds at Chatsworth within the cryonics community, and he is welcomed at both CI and other cryonics functions, where he is treated cordially and has indicated he might reenter the cryonics business in the future.

What was clearly not understood then, or now, is that this “issue” inside cryonics is not a drawing room matter, or even a dirty political backroom matter. It stopped being either of those things when the first patient decomposed at Chatsworth or, more accurately, when Bedford was mishandled by Cryonics Society of California personnel on 12 January, 1967, with the knowledge and complicity of other key people in the cryonics movement.

Specimen Standards for Human

Cryopreservation Organizations Draft 2.4

Core Objectives and Related Considerations

The objective of these specimen standards is to return cryonics to the paradigm that was developed initially by the Cryonics Society of New York (i.e., fairness, openness, use of the scientific method, Evidence Based Cryonics (EBC) and diligent communication of comprehensive and accurate information to cryonics organization members or clients), and greatly elaborated by Alcor under the influence of Jerry Leaf and Mike Darwin in the 1980s. This paradigm can be articulated by the following points:

Organizational (Corporate) Structure & Governance

The organizational structure considered here will be that of the non-profit corporation United States corporation, either charitable (501(c)3) or non-charitable.

The cryonics organization shall be a legally incorporated entity which complies with all applicable federal laws and regulations, as well as applicable laws and regulations of the states and the local jurisdictions in which it is based or operates. If the organization conducts programs outside the United States, it must also abide by applicable international laws, regulations and conventions that are legally binding on the United States.

The organization shall have a formally adopted, written code of ethics with which all of its directors or trustees, staff and volunteers are familiar and to which they adhere and they will adopt and implement policies and procedures to ensure that all conflicts of interest, or the appearance thereof, within the organization and the board are appropriately managed through disclosure, recusal, or other means. This Code of Ethics shall cover accountability, finances, openness, client/member rights, patient rights, confidentiality of medical and cryopreservation records, conduct of staff, and basic procedures for filing and adjudicating grievances within the organization by clients/patients and professional employees.

The cryonics organization shall establish and implement policies and procedures that enable individuals to come forward with information on illegal practices or violations of organizational policies. This “whistle blower” policy should specify that the organization will not retaliate against, and will protect the confidentiality of, individuals who make good-faith reports.

The organization shall have in place policies and procedures to protect and preserve the organization’s important documents and business records.

The organization’s board must ensure that the organization has adequate plans to protect its assets—its property, financial and human resources, programmatic content and material, and its integrity and reputation—against damage or loss. The board should review regularly the organization’s need for general liability and directors’ and officers’ liability insurance, as well as take other actions necessary to mitigate risks.

The organization must have a detailed, written plan of action to protects its patients in cryopreservation against legal or legislative attack, economic instability, insurgent attack by anti-cryonics individuals or entities, as well as plans to cope with and prevail over known existential risks to which its patients may be subject (i.e., hurricanes, tornadoes, earthquakes, blizzards, etc.).

Figure 1: Cryonics organizations must maintain transparency with respect to administrative, financial, scientific, technical and patient care procedures.

Figure 1: Cryonics organizations must maintain transparency with respect to administrative, financial, scientific, technical and patient care procedures.

The organization must make information about its operations, including its governance, finances, programs and activities, widely available to the public. Charitable (501(c)3) organizations shall make information available on the methods they use to evaluate the outcomes of their work and must share the results of those evaluations with members.

The cryonics organization must have a governing body that is responsible for reviewing and approving the organization’s mission and strategic direction, annual budget and key financial transactions, compensation practices and policies, and fiscal and governance policies.

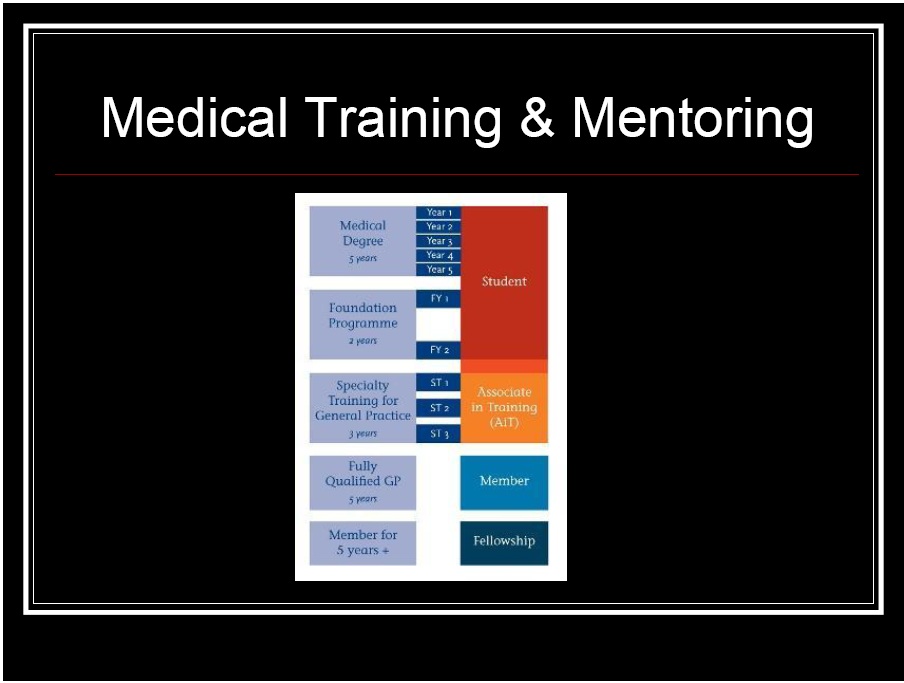

Figure 2: The board of directors of the cryonics organization are elected by the cryopreservation members or clients of the organization who have been cryopreservation members or clients of the cryonics organization for at least 3 consecutive years. Directors’ terms may not exceed 4 years.

The board of directors shall be elected by the cryopreservation members or clients of the organization who have been cryopreservation members or clients of the cryonics organization for at least 3 consecutive years. Cryopreservation members with 10 or more years of consecutive cryopreservation arrangements may, at the organization’s discretion, be granted 2 votes in electing directors.

Candidates for the board shall be examined for psychosocial and fiscal suitability by a thorough, objective and written set of standards and examinations.

Directors term limits, order of service (staggered or otherwise) are that the discretion of the cryonics organization. However the length of any director’s term in office cannot exceed 4 years.

The organization must meet regularly enough to conduct its business and fulfill its duties. Directors’ meetings shall be held monthly and combined directors and membership meeting shall be held no less than annually.

The board of organization should establish its own size and structure and review these periodically. The board should have enough members to allow for full deliberation and diversity of thinking on governance and other organizational matters. Except for very small organizations, this generally means that the board should have at least five members.

The board of the organization must include members with the diverse background (including, but not limited to, ethnic, racial and gender perspectives), experience, and organizational and financial skills necessary to advance the organization’s mission. All directors and officers must be have been cryopreservation members or clients of the organization for a minimum of 3 consecutive years before becoming eligible to serve as a director or officer. In the case of newly forming cryonics organizations, officers and directors must have been members or clients of another cryonics organization for a minimum of 3 consecutive years.

At least two-thirds of the board members, should be independent. Independent members should not: (1) be compensated by the organization as employees or independent contractors; (2) have their compensation determined by individuals who are compensated by the organization; (3) receive, directly or indirectly, material financial benefits from the organization except as a member of the charitable class served by the organization; or (4) be related to anyone described above (as a spouse, sibling, parent or child), or reside with any person so described.

The board shall hire, oversee, and biannually evaluate the performance of the chief executive officer of the organization, and should conduct such an evaluation prior to any change in that officer’s compensation, unless there is a multi-year contract in force or the change consists solely of routine adjustments for inflation or cost of living.

The board of any cryonics organization that has paid staff should ensure that the positions of chief staff officer, board chair, and board treasurer are held by separate individuals. Organizations without paid staff should ensure that the positions of board chair and treasurer are held by separate individuals.

The board shall establish an effective, systematic process for educating and communicating with board members to ensure that they are aware of their legal and ethical responsibilities, are knowledgeable about the programs and activities of the organization, and can carry out their oversight functions effectively.

Board members should evaluate their performance as a group and as individuals no less frequently than every 2 years, and should have clear, written procedures for removing board members who are unable to fulfill their responsibilities.

Beyond the requirement of 3 consecutive years as a cryopreservation member or client, the board shall establish clear policies and procedures setting the length of terms and the number of consecutive terms a board member may serve.

The board should review organizational and governing instruments no less frequently than every 3 years.

The board shall establish and review regularly the organization’s mission and goals and should evaluate, no less frequently than every five years, the organization’s programs, goals and activities to be sure they advance its mission and make prudent use of its resources.

Board members are generally expected to serve without compensation, other than reimbursement for expenses incurred to fulfill their board duties. A charitable organization that provides compensation to its board members should use appropriate comparability data to determine the amount to be paid, document the decision and provide full disclosure to anyone, upon request, of the amount and rationale for the compensation.

The cryonics organization must keep complete, current, and accurate financial records. Its board should receive and review timely reports of the organization’s financial activities and should have a qualified, independent financial expert audit or review these statements annually in a manner appropriate to the organization’s size and scale of operations. For cryonics organizations with more than $500,000 U.S. in assets the independent financial expert must be certified public accountant (CPA).

Cryonics organizations with assets of $1 million U.S., shall have an audit committee composed of independent board members with appropriate financial expertise. By reducing possible conflicts of interest between outside auditors and the organization’s paid staff, an audit committee can provide the board greater assurance that the audit has been conducted appropriately. If state law permits, the board may appoint non-voting, non-staff advisers, rather than board members, to the audit committee.

The board of the organization must institute policies and procedures to ensure that the organization (and, if applicable, its subsidiaries) manages and invests its funds responsibly, in accordance with all legal requirements. The full board should review and approve the organization’s annual budget and should monitor actual performance against the budget.

The cryonics organization should not provide loans (or the equivalent, such as loan guarantees, purchasing or transferring ownership of a residence or office, or relieving a debt or lease obligation) to directors, officers, or trustees.

The organization shall spend at least 30% of its annual budget on programs that pursue its mission. The budget should also provide sufficient resources for effective administration of the organization, and, if it solicits contributions, for appropriate fundraising activities.

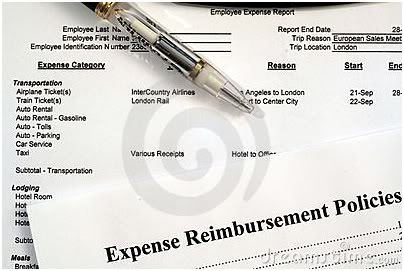

Figure 3: Reimbursement for expenses, as well as compensation for services for directors must be unambiguous and in written form.

Figure 3: Reimbursement for expenses, as well as compensation for services for directors must be unambiguous and in written form.

The cryonics organization shall establish clear, written policies for paying or reimbursing expenses incurred by anyone conducting business or traveling on behalf of the organization, including the types of expenses that can be paid for or reimbursed and the documentation required. Such policies should require that travel on behalf of the organization is to be undertaken in a cost-effective manner.

The organization shall neither pay for nor reimburse travel expenditures for spouses, dependents or others who are accompanying someone conducting business for the organization unless they, too, are conducting such business.

Solicitation materials and other communications addressed to donors and the public must clearly identify the organization and be accurate and truthful.

Without exception, contributions must be used for purposes consistent with the donor’s intent, whether as described in the relevant solicitation materials or as specifically directed by the donor.

The organization, if a 501(c)3, must provide donors with specific acknowledgments of charitable contributions, in accordance with IRS requirements, as well as information to facilitate the donors’ compliance with tax law requirements.

The organization must have clear, written policies, based on its purpose as a cryonics organization to determine whether accepting a gift would compromise its ethics, financial circumstances, program focus or the well-being of the patients in its care.

The cryonics organization should provide appropriate training and supervision of the people soliciting funds on its behalf to ensure that they understand their responsibilities and applicable federal, state and local laws, and do not employ techniques that are coercive, intimidating, or intended to harass potential donors.

The organization shall not compensate internal or external fundraisers based on a commission or a percentage of the amount raised.

The cryonics organization shall respect the privacy of individual donors and, except where disclosure is required by law, shall not sell or otherwise make available the names and contact information of its donors without providing them an opportunity at least once a year to opt out of the use of their names.

The board shall prepare a written job description for individual board members as well as prepare an annual schedule of meetings, determined a year in advance.

The board she see to it its members receive clear and thorough information materials, including an agenda, to all members two to three weeks before each meeting.

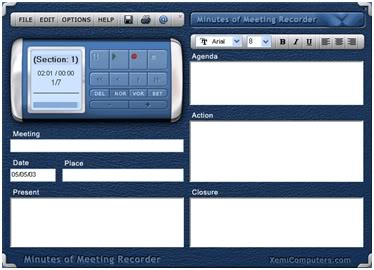

Figure 4: The comprehensive and complete minutes of every directors’ meeting must be recorded on paper, as well as electronically and must be c9ompiled into readily accessible books or volumes for inspection by cryopreservation members or clients at any reasonable time. Similarly, electronic copies of minutes shall also be available so that members distant from the organization’s headquarters may have access to the minutes.

Figure 4: The comprehensive and complete minutes of every directors’ meeting must be recorded on paper, as well as electronically and must be c9ompiled into readily accessible books or volumes for inspection by cryopreservation members or clients at any reasonable time. Similarly, electronic copies of minutes shall also be available so that members distant from the organization’s headquarters may have access to the minutes.

The cryonics organization shall maintain complete and accurate minutes of all meetings which shall be gathered into volumes organized by month and year. These minutes shall be kept at the cryonics organization’s principal place of business and be available for inspection upon the request of any cryopreservation member or client. Additionally, multiple electronic copies shall be kept in discrete separate locations to prevent loss due to existential or other disasters and so that they can be made available to members or clients who are far distant from the organization’s principal place of business.

Each board member shall serve on at least one board committee or task force. (For new members, one committee assignment is sufficient.)

The board shall prepare written statements of committee and task force responsibilities, guidelines and goals. These organizational documents, which should be approved by the board chair, are to be reviewed annually, and revised if necessary. The CEO shall assign an appropriate staff member to work with each committee

The board shall create a written system of checks and balances to monitor committee members’ work and assure that tasks are completed on schedule.

Nondiscrimination

The medical model of cryonics as an emergency room (Accident & Emergency) where all comers able to meet the publicly specified requirements of the organization are competently and equally treated, regardless of age, religion, politics, criminal history, gender, sexual orientation, community influence, or celebrity. “Equally” is understood to mean here that all clients will receive the same minimum standards of care set out as being available upon meeting the specified minimum requirements of the organization. It does not imply that higher standards of care may not be paid for by clients able to afford them. However, it does mean that if such higher standards are offered, or are available for an added fee or other considerations, that all clients shall be apprised of the availability of such non-standard services, as soon as such options are made available.

Figure 5: Cryonics organizations must not discriminate on the basis of age, religion, politics, criminal history, gender, sexual orientation, community influence, or celebrity.

Additionally, the cryonics organization shall adopt the following non-discrimination policy:

The cryonics organization believes that every person has a right to choose and arrange for his or her own cryopreservation and to enjoy its possible benefits of greatly extended lifespan. To this end, the cryonics organization does not discriminate against any person on the basis of race, religion, color, creed, age, marital status, national origin, ancestry, sex, sexual orientation or preference, medical condition, or handicap.

However, nothing in this statement prevents the cryonics organization from avoiding any situation that genuinely threatens the health or safety of cryonics organization employees, volunteers, patients in cryopreservation, or the public, or from requiring reasonable medical evaluations in some instances where a genuine threat to health or safety may be suspected to exist, or where the legal status of an individual with regard to mental competency may be in question.

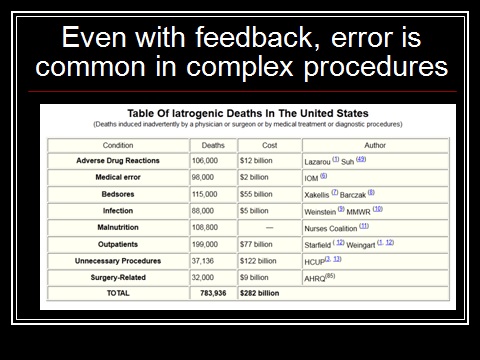

Feedback, Quality Assurance & Quality Control

Quality control measures which provide feedback about the nature and effectiveness of all of the organization’s procedures will be publicly disclosed in an open and timely fashion. This is understood to include not only medical, cryobiological, patient care, or other technical and scientific procedures, but also financial, administrative and business procedures as well. Both classes of disclosure, technical and administrative, will be discussed with varying level of detail in this document. In administrative areas where there are long established and demonstrably workable resources, the discussion will be more superficial. In technical, ethical and other areas where there is little or no precedent, the discussion will be exhaustive and often accompanied by detailed examples of the required work product.

The clear message of this point is that a culture of openness and accountability is perhaps the most important ingredient to the long term success of any cryonics organization or, for that matter, any quality scientific, technical, or medical institution.

It is important to digress briefly here and discuss the problematic nature of such a high degree of accountability with respect to cryonics organizations, in particular. All human institutions, whether cryonics organizations or otherwise, find this level of accountability difficult to achieve. There are many reasons for this; however these two are by far the most significant: the basic human desire to avoid owning failure, error or misdeeds, and the ammunition public knowledge of failure, error, or misdeeds provides an enemy[1] — which segues into the next point.

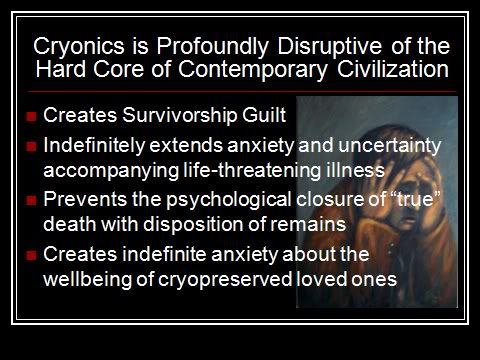

Need for a Defensive Organization (a.k.a. Cryonics Defense League)

Cryonics as a whole has become fear-driven and in nearly constant crisis mode. Crises driven operation is necessarily mostly reactive rather than proactive. This is not how any successful organization advances scientifically or financially. Indeed, it is not how success is achieved in any area of organizational operations, even in successfully defending the organization in the long run. Because of this situation it is especially difficult for cryonics organizations to have a high level of accountability, even about seemingly harmless facts pertaining to their procedures and policies, because cryonics is not an established business institution, has an (arguably) increasing number of serious enemies, is widely misunderstood, has been subject to unjustified distortion and sensationalism, has been subjected to repeated rounds of invasive and destructive media siege, and is increasingly coming under governmental scrutiny. Under such circumstances it is completely understandable for a “bunker mentality” to develop.

Cryonics as a whole has become fear-driven and in nearly constant crisis mode. Crises driven operation is necessarily mostly reactive rather than proactive. This is not how any successful organization advances scientifically or financially. Indeed, it is not how success is achieved in any area of organizational operations, even in successfully defending the organization in the long run. Because of this situation it is especially difficult for cryonics organizations to have a high level of accountability, even about seemingly harmless facts pertaining to their procedures and policies, because cryonics is not an established business institution, has an (arguably) increasing number of serious enemies, is widely misunderstood, has been subject to unjustified distortion and sensationalism, has been subjected to repeated rounds of invasive and destructive media siege, and is increasingly coming under governmental scrutiny. Under such circumstances it is completely understandable for a “bunker mentality” to develop.

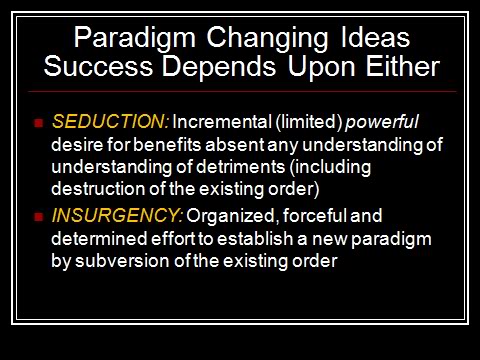

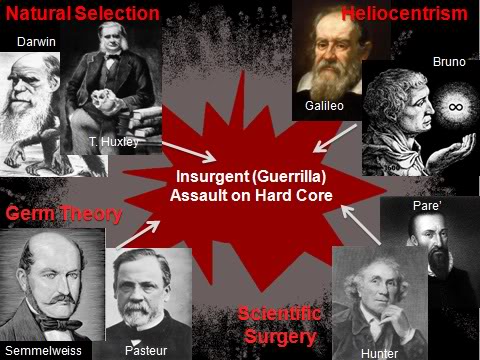

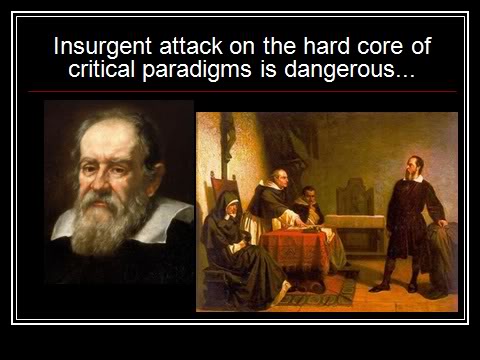

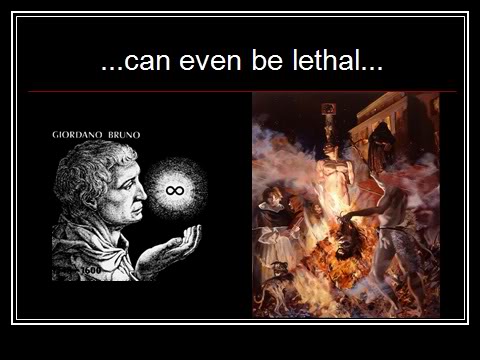

Further, in order to protect its human cryopatients, a cryonics organization may have to develop not only a bunker mentality, but very aggressive and covert means to defend the well being of its patients. The author has spent the past several years reading extensively the history of emerging medical, social, political and religious movements. In no case was social acceptance or tolerance of any major paradigm changing movement achieved without the use of force and fraud. I even include Darwin’s theory of evolution in this analysis since, as Stephen Jay Gould noted just a few years ago in his book The Structure of Evolutionary Theory, Evolution is neither widely understood nor accepted – this, more than a hundred years after it was publicly espoused.

Cryonics organizations need a separate, defensive organization which can act semi-covertly or covertly as needed to deal with lethal threats, which all conventional approaches have failed to stop. Separating defensive capability from other operations would allow accountability to continue in every area of operations except the last and most desperate measures needed for defense of patients and members. This would allow some measure of psychological tranquility to exist in the organization as a whole, even in the midst of extreme threats, and thus for business as usual to continue and a high degree of experimentation and openness to be maintained even under difficult circumstances. The most immediate analogy is one of the intelligence and military apparatus of a nation-state. Because these assets exist in a hostile world it is not necessary for citizens, businesses, churches, or charities to anguish over every threat to their existence. Yes, in times of severe crises, or all out attack, all of these entities may divert some or all of their efforts, attention, and support to the crisis, but on a daily basis, it is not necessary that they be consumed with the problems of their own defense. However, more relevant analogies would the Jewish Defense League (JDL) or the Worldwide Guardian Office employed by Scientology.

Until cryonics organizations can rely on a defense force which is competent and properly equipped to deal with even the worst crises, the organization as a whole will be drained of energy and other resources, and most importantly, will be paralyzed by anxiety, and become increasingly afraid to take any actions which expose more of its flank to attack. This is a response characteristic of most life forms more complex than viruses, and is one which must be dealt with. Every organization charged with protecting the survival of its members has such defensive mechanisms, from the amoebae to the U.S. Federal Government. This is a critical need, which has heretofore been unappreciated in cryonics. The absence of such a defensive mechanism in cryonics is the principal cause of the increasing risk-averseness, and willingness to surrender authority over patients to the regulatory bodies of nation-states.

End of Part 1

By introduction, I am Dave Crippen, MD, Professor of Critical Care Medicine and Neurological Surgery at the UPMC Medical Center in Pittsburgh. Some of you may know me. I’m the moderator for 18 years duration of CCM-L, the International Critical Care Internet Group (~1000 members). If you ask almost anyone in the in critical care medicine global village, they probably know me, or know of me.

By introduction, I am Dave Crippen, MD, Professor of Critical Care Medicine and Neurological Surgery at the UPMC Medical Center in Pittsburgh. Some of you may know me. I’m the moderator for 18 years duration of CCM-L, the International Critical Care Internet Group (~1000 members). If you ask almost anyone in the in critical care medicine global village, they probably know me, or know of me.

A Brief History of Attempts to Create and Implement Minimum Standards in Cryonics

A Brief History of Attempts to Create and Implement Minimum Standards in Cryonics

Figure 2: Vaughn Bode’s CSA logo of a side-view of a Phoenix in flight.

Figure 2: Vaughn Bode’s CSA logo of a side-view of a Phoenix in flight.

Figure 4: Robert F. Nelson, President of the Cryonics Society of California

Figure 4: Robert F. Nelson, President of the Cryonics Society of California

Figure 1: Cryonics organizations must maintain transparency with respect to administrative, financial, scientific, technical and patient care procedures.

Figure 1: Cryonics organizations must maintain transparency with respect to administrative, financial, scientific, technical and patient care procedures.

Figure 3: Reimbursement for expenses, as well as compensation for services for directors must be unambiguous and in written form.

Figure 3: Reimbursement for expenses, as well as compensation for services for directors must be unambiguous and in written form. Figure 4: The comprehensive and complete minutes of every directors’ meeting must be recorded on paper, as well as electronically and must be c9ompiled into readily accessible books or volumes for inspection by cryopreservation members or clients at any reasonable time. Similarly, electronic copies of minutes shall also be available so that members distant from the organization’s headquarters may have access to the minutes.

Figure 4: The comprehensive and complete minutes of every directors’ meeting must be recorded on paper, as well as electronically and must be c9ompiled into readily accessible books or volumes for inspection by cryopreservation members or clients at any reasonable time. Similarly, electronic copies of minutes shall also be available so that members distant from the organization’s headquarters may have access to the minutes.

Cryonics as a whole has become fear-driven and in nearly constant crisis mode. Crises driven operation is necessarily mostly reactive rather than proactive. This is not how any successful organization advances scientifically or financially. Indeed, it is not how success is achieved in any area of organizational operations, even in successfully defending the organization in the long run. Because of this situation it is especially difficult for cryonics organizations to have a high level of accountability, even about seemingly harmless facts pertaining to their procedures and policies, because cryonics is not an established business institution, has an (arguably) increasing number of serious enemies, is widely misunderstood, has been subject to unjustified distortion and sensationalism, has been subjected to repeated rounds of invasive and destructive media siege, and is increasingly coming under governmental scrutiny. Under such circumstances it is completely understandable for a “bunker mentality” to develop.

Cryonics as a whole has become fear-driven and in nearly constant crisis mode. Crises driven operation is necessarily mostly reactive rather than proactive. This is not how any successful organization advances scientifically or financially. Indeed, it is not how success is achieved in any area of organizational operations, even in successfully defending the organization in the long run. Because of this situation it is especially difficult for cryonics organizations to have a high level of accountability, even about seemingly harmless facts pertaining to their procedures and policies, because cryonics is not an established business institution, has an (arguably) increasing number of serious enemies, is widely misunderstood, has been subject to unjustified distortion and sensationalism, has been subjected to repeated rounds of invasive and destructive media siege, and is increasingly coming under governmental scrutiny. Under such circumstances it is completely understandable for a “bunker mentality” to develop.

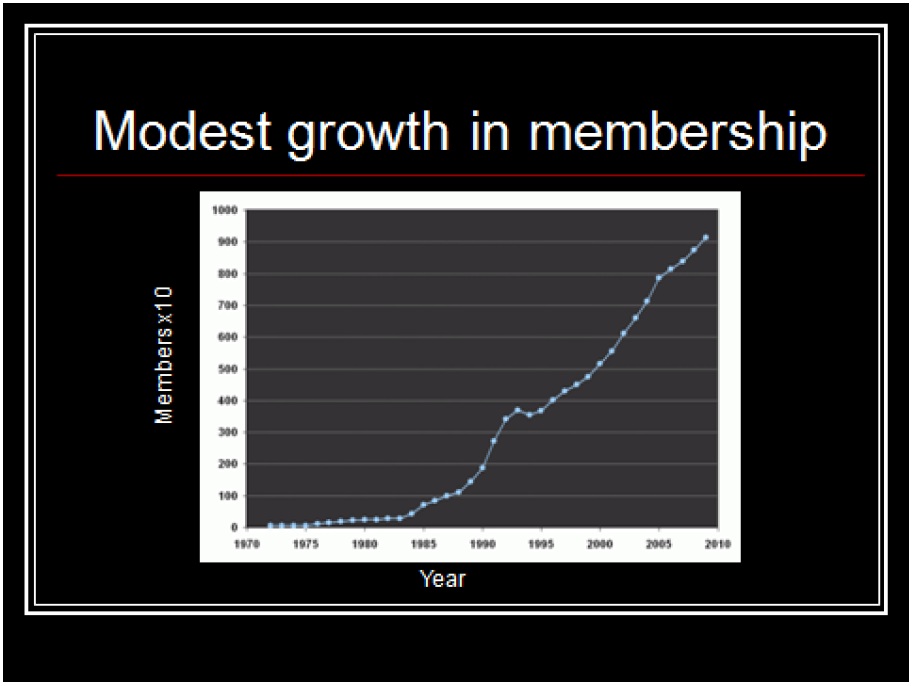

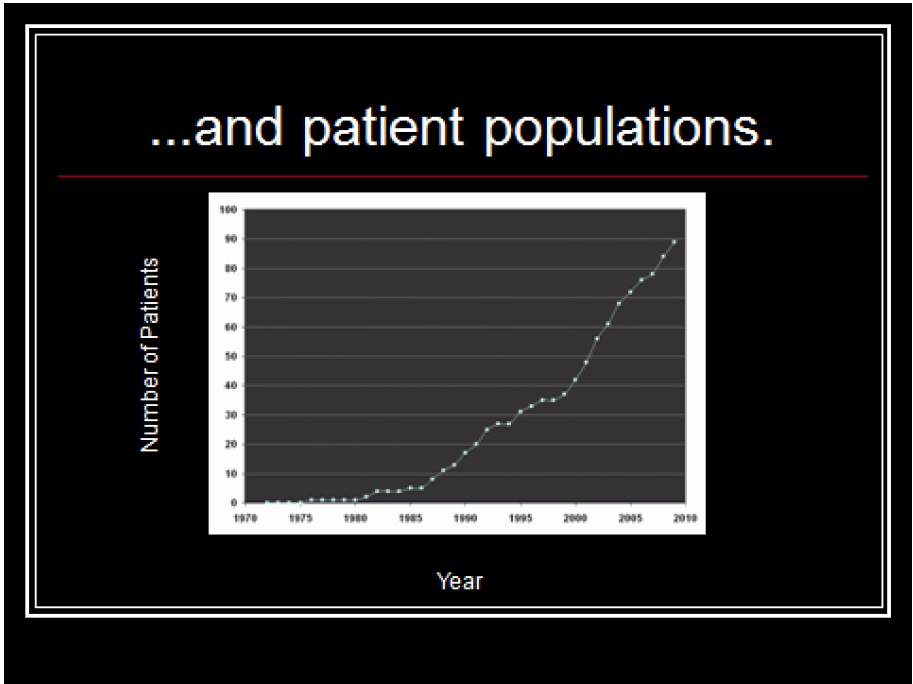

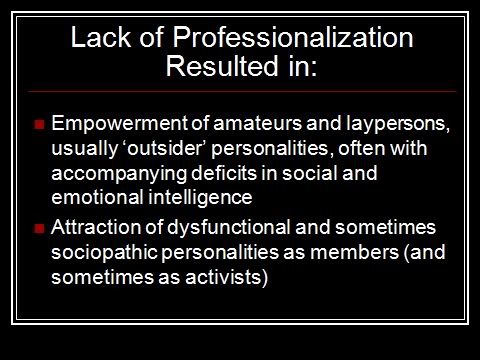

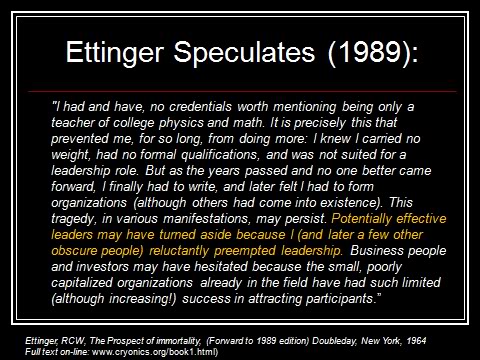

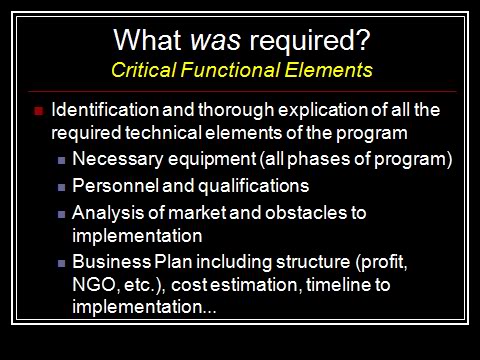

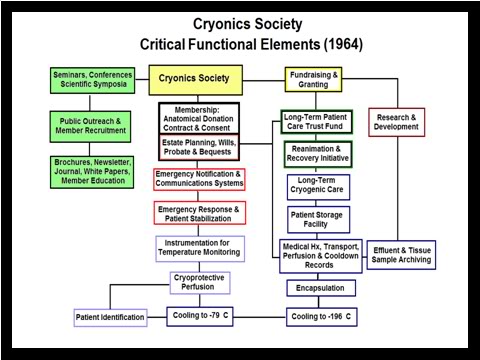

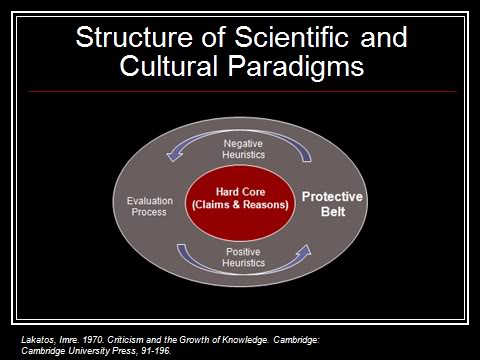

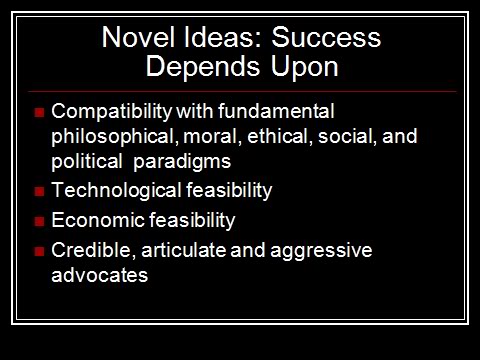

SLIDE 11

SLIDE 11

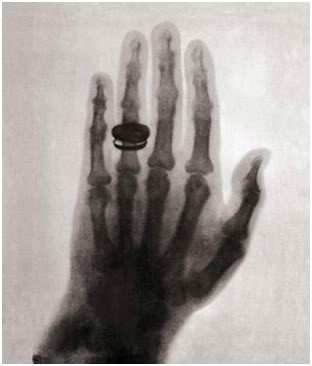

Figure 34: First x-ray of human hand; Anna Bertha Röntgen, 1895.

Figure 34: First x-ray of human hand; Anna Bertha Röntgen, 1895.