Screening for the Risk of Deanimation

The term “screening” is used in medicine to describe routine examinations or diagnostic procedures of a defined group of individuals to identify diseases or risk factors for same at an early stage. Screening is usually categorized as a “preventive medical examination” or a “checkup,” and its aim is to increase the life expectancy of those examined by reducing the incidence or severity of life threatening disease and enhancing the quality of life. The most accurate examination methods possible should be used to identify as many diseases as possible still in their non-symptomatic phase, so that early treatment or change in life style can be initiated.

It is critically important to understand that the purpose of a “deanimation screening scan” (DSS) is not primarily to interfere with the course of disease or to extend the duration of life during this life cycle. Rather, it is to predict or to warn of impending deanimation with increased accuracy and precision. Any contemporary medical or health benefits are thus incidental. Indeed, it is precisely when DSSing is used to determine or influence current medical interventions that it becomes dangerous. Knowing when you are likely to deanimate with greater precision, for sole purpose of improving your cryopreservation, carries little if any risk of iatrogenesis beyond that which would be present if you found out you were dying at a later time, or didn’t find out and suddenly collapsed in cardiac arrest from a heart attack, or suffered a massive stroke. It is only when the course of treatment is altered by obtaining the data, or looking at it (see “The Black Box of the Baseline,” below) that DSSing becomes either a practical or an ethical conundrum.

The first problem we confront in a screening test for deanimation risk is that we are moving in completely uncharted waters. We have no benchmarks or baselines on which to structure our screening program, save for a modest number of pilot programs that have been undertaken to evaluate full body scanning as a primary tool for the detection of cancer and atherosclerosis in the general population, or in selected subpopulations. For now, these will have to serve as the basis for our protocols, as well as the important cautionary lessons learned from other screening programs.

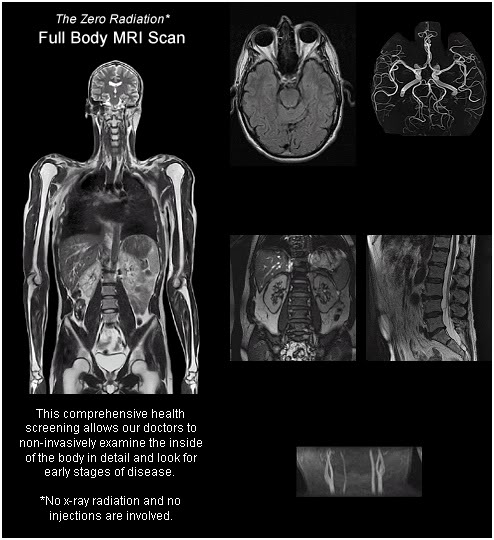

For reasons of safety, (see Radiation & Risk, below) Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is preferred over Computerized Tomography (CT), because no ionizing radiation is employed in making the image. MRI has some important limitations at this time, most notably only a few centers have devices that image the coronary vessels with sufficient precision to allow risk assessment for coronary artery disease (CAD). Similarly, screening for Alzheimer’s Disease (AD),(beta amyloid deposits) also requires CT-PET scanning and the associated exposure to ionizing radiation. So, for the present, CT is the only way to screen for CAD and AD. For this reason, and for those who for economic reasons may need to use CT imaging, it is worthwhile to briefly discuss the much hyped “risks” of radiation from whole body CT scans and this is done in some detail below.

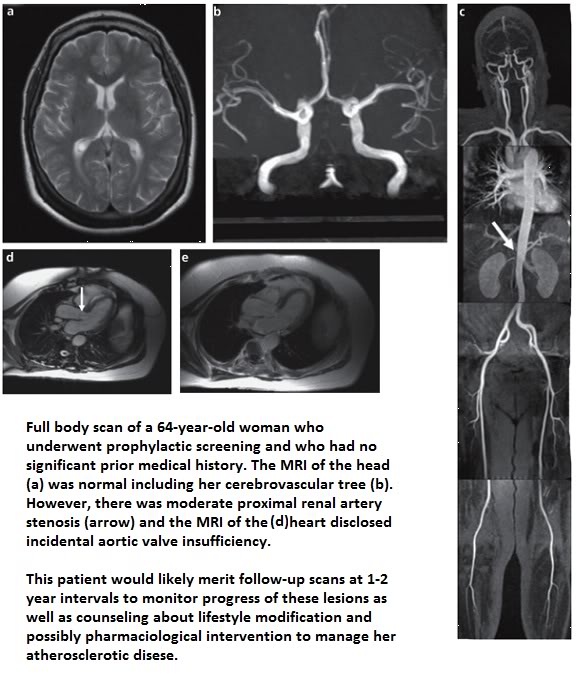

Figure 25: Typical finding in an elderly woman who under prophylactic full body MRI scanning during a clinical trial in Germany to determine if full body scanning would reduce morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular disease and cancer. (Gohde, et al.)

Figure 25: Typical finding in an elderly woman who under prophylactic full body MRI scanning during a clinical trial in Germany to determine if full body scanning would reduce morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular disease and cancer. (Gohde, et al.)

A specimen imaging protocol is presented as Appendix 1 and is taken from the study by Gohde, et al., “Prevention without radiation – a strategy for comprehensive early detection using magnetic resonance imaging,” which was itself a pilot study in the use of MRI as a screening tool for cancer and cardiovascular disease.

The Mechanics

Currently, there is only one way to get a DSS and that is to do it yourself. There are several reasons, which will be discussed directly, why that is not a good idea, or certainly not the ideal way to pursue DSSing. There are a number of reasons for this, starting with the potential for harm. Primum non nocere is the first dictum in medicine: first do no harm. Information is the most powerful force in the universe and information concerning you own health and welfare is especially important. It is also information that you cannot be objective about. It just isn’t possible. It is for this reason that no good physician treats himself or his immediate family in life or death matters as the sole or usually even the primary caregiver. In fact, speaking from experience as a person knowledgeable in medicine, I have found that wise counsel and advice I can (and do) easily give to others is strangely absent from my own ears when I am the patient.

This lack of objectivity is more than a nuisance, it can be truly dangerous; and here I will have recourse to an actual example. The first four people to undergo DSSing have done so over the past 11 months. These were all individuals who were over 60 and who had not had consistent (or recent) “physicals.” All were counseled about the dangers of VOMIT and about the negative psychological impact of potentially finding out “something was wrong.” All four individuals had significant anomalies on their scans – two of which were life threatening and these were (or are) being medically managed.

In the other two cases, the scans revealed anomalies that might merit further medical evaluation in testing, and in both cases, the decision was wisely made not to pursue those tests. Why? That’s a complicated question, and I’ll answer it by explaining the circumstances of one of these people:

Mr. Ling is an 82 year old man who is in excellent health. He is physically active, mentally sharp and still working part time in his profession of many years. He underwent a DSS five months ago. The findings were, overall, very good. His coronary calcium score was roughly a third lower than expected for his age, he had no signs of neoplasms, or of peripheral or central atherosclerosis, and the only abnormal cardiovascular finding was evidence of mitral valve regurgitation, which was deemed not serious and not likely to progress rapidly. However, a number of nodules were found in his right lung, along with some enlarged lymph nodes. The radiologist who reviewed the scan suggested a possible biopsy, with or without “bronchoalveolar lavage” (BAL).

While Mr. Ling is in good health, he is an 82 year old man and BAL requires sedation with propofol or a similar drug, and carries with it the risk of significant complications. As to a CT-guided needle biopsy of the lung masses or the lymph nodes, this is this discussion that took place between Mr. Ling and the radiologist who interpreted his scan: “OK, let’s consider what this could be? I’m not sick – never felt better, so it’s not TB or something infectious? And if it’s cancer, well, what kind of treatment options would I have at my age for lung cancer with lymph node involvement?”

While Mr. Ling is in good health, he is an 82 year old man and BAL requires sedation with propofol or a similar drug, and carries with it the risk of significant complications. As to a CT-guided needle biopsy of the lung masses or the lymph nodes, this is this discussion that took place between Mr. Ling and the radiologist who interpreted his scan: “OK, let’s consider what this could be? I’m not sick – never felt better, so it’s not TB or something infectious? And if it’s cancer, well, what kind of treatment options would I have at my age for lung cancer with lymph node involvement?”

Those were great questions, and as it turned out, the radiologist was only playing it safe – he doesn’t want to get sued if Mr. Ling finds out he has cancer and a lawyer says to a jury, “The doctor who imaged him said, ‘You’re in you 80s, I see this kind of thing all the time. Don’t worry about it.” The radiologist ended by noting, “Since you are planning on following up in a year with another scan, we’ll see if anything has changed then.” And Mr. Ling is fortunate to have sufficient financial means that if he wants to pop in for a scan two months later, he can do that, too.

The problem is, most people aren’t in Mr. Ling’s position, and many will be unable to reason their way past the information that they have “masses” or “lumps” in their lungs and “enlarged lymph nodes in their chests!” That kind of worry cannot only be expensive, it can be damaging to one’s health, and corrosive to one’s quality of life. The information from DSSing should be given in the proper context, in the proper way, by the proper people, with the proper knowledge. Absent that, it can do real harm. And if the scan does reveal a grave or untreatable medical condition, then there is all the more reason for the person to have the necessary resources at hand to help him cope and plan.

Ideally, this program would be part of a comprehensive Member Survival Program (MSP) administered by the cryonics organization (CO) and there would be a staff person whose job it would be to maintain communications with members, encourage compliance with MSP protocols (including the preferred imaging protocol) and collect and manage the resulting data stream.

Under such a scheme, upon intake (approval of cryopreservation arrangements) all members would have (at their option) completed a comprehensive health history and demographic information questionnaire, most of which would be completed as part of their membership application. The data from this questionnaire, as well as any electronic medical records the member may choose to provide, would be entered into the CO’s comprehensive member data base. The availability of this data would then allow for downstream refinement of the “one size fits all” scan protocol being proposed here, by allowing for individual risk assessment for CVD and cancer. This would flag members at elevated risk of early onset of these diseases to consider commencing scanning surveillance at an earlier age.

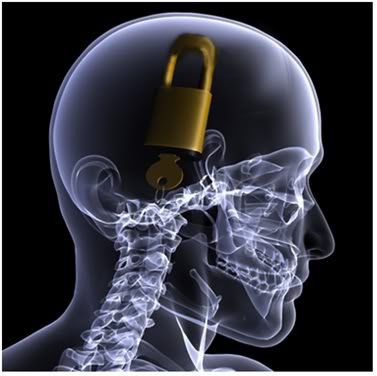

The Schrödinger Scan: the Black Box of The Baseline

Unless otherwise indicated, the first (baseline) scan would be done at age 45 for men and age 50 for women. In order to completely avoid any deleterious negative psychological effects, as well any potentially harmful effects from VOMIT (as discussed above), the baseline scan remains blinded and unexamined for 1 year after it is made. This done by providing written instructions to the radiologist reviewing the scan to seal the report unless there are unequivocal findings of life threatening pathology.

At the end of the year long blind period, the scan is examined and any anomalies noted. If the member chooses, a repeat scan can be done to resolve any questions or concerns raised by the baseline imaging. For example, if what appears to be a suspicious mass or nodule was found, a rescan a year later will very likely disclose if it is a neoplasm e.g., it will have grown or spread). It may seem counter intuitive to not look at data which you have paid for, experienced inconvenience to get, and which “might” save your life, but that is the necessary price that must be paid for this intervention to be used safely.

The baseline scan must be regarded as the first part of something that will not “happen,” or be completed for another year – like a bulb that has been planted to bloom in the spring, or a bond that will not mature for another 12 months. The scan itself is only a part of the process: the necessary information to safely interpret it does not appear until the required interval of time has elapsed. After all, before this protocol was proposed, no one ever got scanned and they felt just fine about it (until they dropped over in cardiac arrest). For those of a quantum bent, consider it an extended version of Schrödinger’s famous experiment, except instead of the cat in the box, it’s a CAT scan in the box.

The baseline scan must be regarded as the first part of something that will not “happen,” or be completed for another year – like a bulb that has been planted to bloom in the spring, or a bond that will not mature for another 12 months. The scan itself is only a part of the process: the necessary information to safely interpret it does not appear until the required interval of time has elapsed. After all, before this protocol was proposed, no one ever got scanned and they felt just fine about it (until they dropped over in cardiac arrest). For those of a quantum bent, consider it an extended version of Schrödinger’s famous experiment, except instead of the cat in the box, it’s a CAT scan in the box.

Scan Intervals & Exceptions

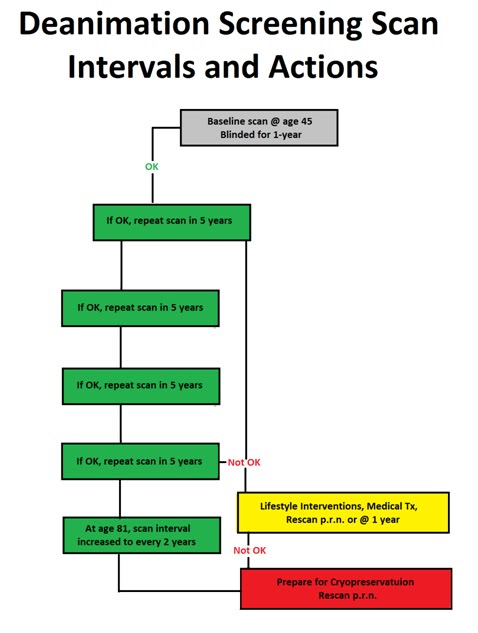

If the baseline is “negative,” showing no evidence of evolving pathological processes that merit intervention or further monitoring, then it is being proposed that the next scan take place 5 years later. Similarly, with each subsequent negative “healthy” scan, the next scan would be 5 years hence until age 81, at which point scans would be done every 2 years until cryopreservation ensues.

Figure 26: Proposed algorithm for Deanimation Screening Scan intervals and actions.

These scan intervals are arbitrary and will no doubt need to be refined over time as experience is gained. Intuitively, it seems that there should be a relationship between scan intervals and increasing age, and it is possible to configure scan intervals based on things like increasing risk of SCA or terminal illness with age. However, until some real world experience is gained, a conservative approach which minimizes costs and maximizes the opportunity for benefit, seems best. There are lots of programmers, mathematicians and similarly qualified people in cryonics and if any are interested in working with me, I am interested in generating scan interval algorithms based on the rising risk of disease and death with age (if you are interested, contact me at m2darwin@aol.com)

Going it Alone?

If a decision is made to proceed with DSSing on an individual basis, there are a number of important things to keep in mind and to do:

* Do consider carefully the possible impact this decision will have on you and on your family. In fact, give some thought to discussing this with your spouse or significant other before moving ahead.

* Do select a good imaging center with competent and caring staff who can give you good counsel about the procedure and the results. Imaging centers that offer full body scans are often used to counseling patients: make sure the one you select is a good one. Talk with the staff about your concerns before you commit to being imaged.

* Do explain to the radiologist who will interpret your images that you are having a baseline scan done and you only want to know if there is unequivocal pathology present that requires immediate or urgent medical intervention. If you can’t get that assurance from him, ask for your results only in writing on the same disk on which your scan is written.

* Don’t look at your scan or the written report that accompanies it. If you have a reliable and willing CO, send a copy to them and ask them to send you the results a year from when they receive the media with the images and the report on it. Duplicate CDs are typically made and given upon request at no charge, or for a small fee at the time you are imaged, or when you come for your results. Bring your own media to save money!

* Don’t look at your scan or the written report that accompanies it. If you have a reliable and willing CO, send a copy to them and ask them to send you the results a year from when they receive the media with the images and the report on it. Duplicate CDs are typically made and given upon request at no charge, or for a small fee at the time you are imaged, or when you come for your results. Bring your own media to save money!

* Do provide a copy of the disk with the scan on it to your medical surrogate and to anyone who is on you ICE (in case of emergency) contact list on your mobile phone. The reason for doing so is that, should you experience SCA during the blinded waiting period, the scan may still save you from autopsy if it documents the presence of CAD, or some other pathology that could have caused your sudden and unexpected deanimation.

* Don’t rely on the DSS to keep you out of trouble, or to reassure that everything is OK, should you develop serious health concerns. Just because a scan shows no indication of pathology does not necessarily mean that there is none. If you have signs or symptoms that would have prompted medical attention absent scanning, act on them in the same way after scanning. Let your physician decide if the scan is significant in the context of any illness or concerns.

* Don’t forget that the scan intervals are 5 years and that is more than enough time for serious disease to develop. Indeed, the 5 year window is a long one, especially where cancer is concerned. A DSS is not a health promotion or a disease prevention program. It’s primary purpose is to let you know you are terminally ill, not to assist you in avoiding that eventuality.

* Do know that if you have atherosclerosis, “vasculopathy” and you want to monitor progression of the disease, your scan intervals will have to be much shorter than 5 years – probably 6 months to 1 year, depending upon the severity, your response to medical intervention, and so on.

Economies of Scale?

Medical imaging is a highly competitive, non-monolithic industry consisting of many operators, large and small, both independent and institutionally affiliated. Such market environments inevitably encourage the drive to survive, and thus typically offer the discriminating consumer the opportunity for real bargains. I made a number of calls to imaging centers around the US and discussed the possibility of group discounts and “scan plans” wherein members of an organization or group, even just a group of like minded individuals, could get deep discounts on scans. The majority of centers I spoke with were receptive to this idea, and several discussed specific numbers which were anywhere from 20% to 60% lower than their standard walk-in fee.

Thus, it should be possible for groups of cryonicists in a given geographical area to make arrangements with a local imaging center for scans. The same was also true when I inquired about group or institutional discounts for carotid and abdominal ultrasound screenings, with the difference being that in some cases, prices went from ~ $350 per screen to ~ $60 per screen, providing the group could be scheduled for the same time and place.

The Pre-Cryopreservation Baseline CT Scan

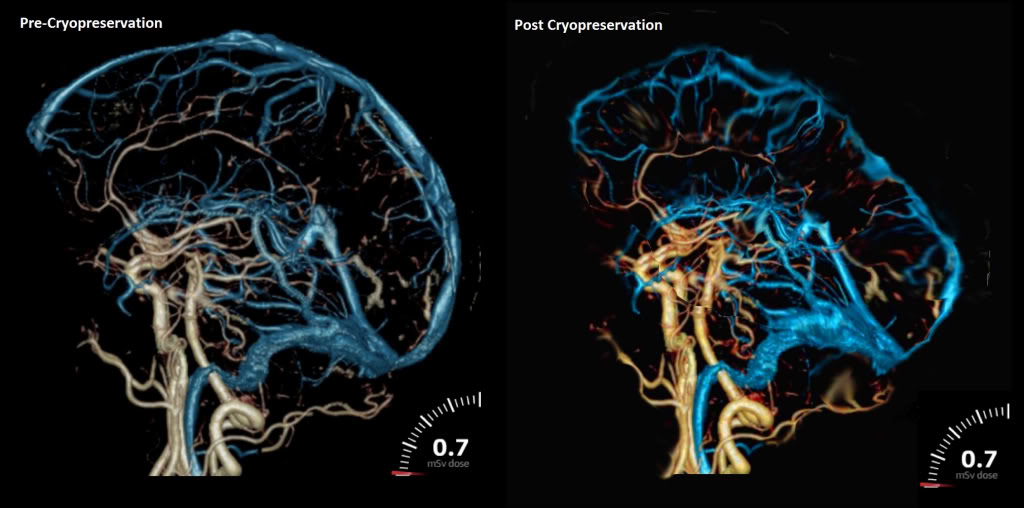

Figure 27: A hypothetical pre- and post-cryopreservation CT cerebral angiogram. The post-perfusion image would be obtained by administering radiocontrast agent(s) into the perfusate immediately, or shortly before discontinuing cryoprotective perfusion, prior to deep cooling to storage temperature.

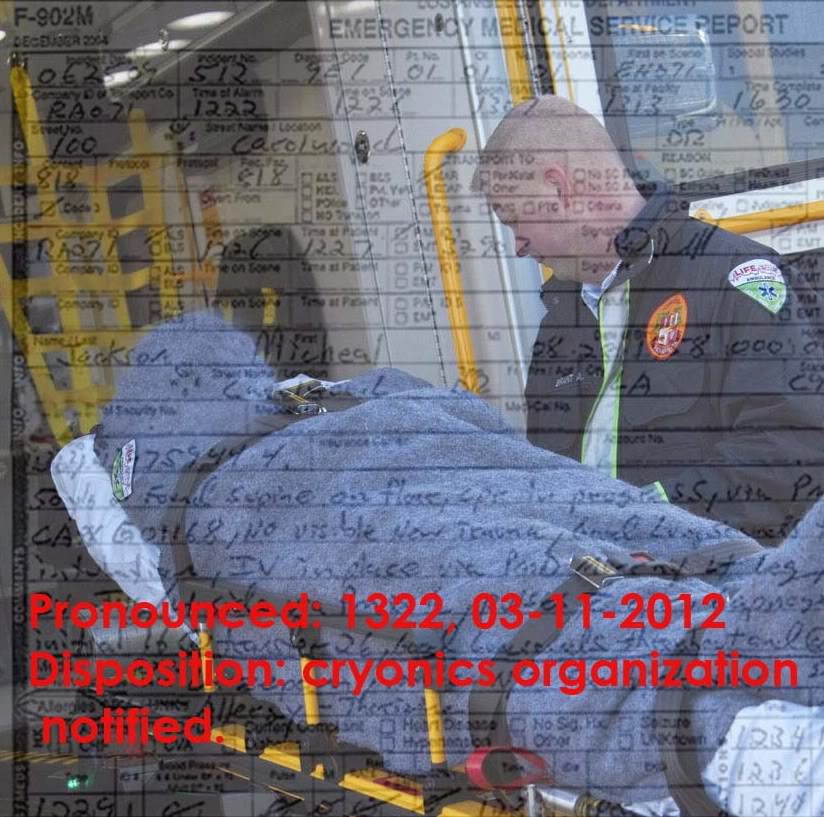

If it is at all possible, a final vital CT scan of the head (at least) should be done as close to the time of cryopreservation as possible. This scan should be done with contrast and with no concerns about clinical radiation dose limitations, since the member will be terminal. The objective of this scan is to document, in as much detail (highest resolution) possible, the morphology of the brain and its vasculature. The imaging technique used should be one that optimizes resolution of the cerebral angiogram. The reason for making these images is that they should allow for many important determinations about the quality of initial stabilization and cryoprotective perfusion and cryoprotectant distribution in the brain to be made, at leisure, during the period the patient is in storage.

If contrast agent(s) is injected into the perfusion circuit shortly, or immediately prior to the discontinuation of perfusion, it should be possible to obtain a post-vitrification angiogram, which in turn should allow for evaluation of cerebrovascular patency, as well as assist in determining the anatomical landmarks within the cryopreserved tissue. It should also be possible to add other kinds of tracers to the perfusate, which might allow for quantification of regional distribution of cryoprotectants, or of other molecular species of interest not only within the brain vasculature, but within the brain parenchyma, as well. Again, the presence of a baseline pre-cryopreservation scan will likely be of great importance in allowing accurate interpretation of post-cryopreservation images.

This scan must be a CT, as opposed to an MRI, since MRI scans are unobtainable in deep hypothermia, or in the solid state.

Radiation & Risk

When the mass media talk about the “risks” from radiation associated with CT scanning, the first question that should spring to mind is, “Risks to who?” Sensitivity to ionizing radiation varies based on the cell age and mitotic cycle, and what this means in practical terms is that the younger you are, the greater the risk radiation presents to you. Children thus have a much higher relative risk when compared to adults due to their rapid cell division and cell differentiation rate.

When the mass media talk about the “risks” from radiation associated with CT scanning, the first question that should spring to mind is, “Risks to who?” Sensitivity to ionizing radiation varies based on the cell age and mitotic cycle, and what this means in practical terms is that the younger you are, the greater the risk radiation presents to you. Children thus have a much higher relative risk when compared to adults due to their rapid cell division and cell differentiation rate.

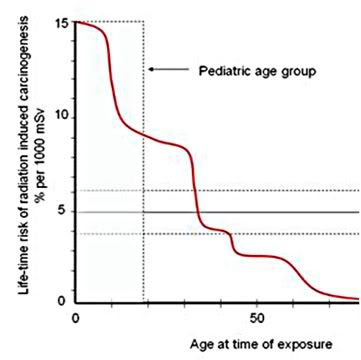

Figure 28: The risk of developing cancer as a result of radiation exposure is strongly age dependent and decays dramatically as people age. By the time an individual is in his 60s, 70s or 80s, the risk of neoplastic disease from medical imaging becomes negligible. Adapted from ICRP Publication 60 (1990).

| Table 1: Nominal Risk for Cancer Effects * | |

| Exposed population | Excess relative risk of cancer (per Sv) |

| entire population | 5.5% – 6.0% |

| adult only | 4.1% – 4.8% |

| *relative risk values based on ICRP publications 103 (2007) and 60 (1990) | |

| Table 2: Relative Radiation Level Scale | |

| Relative Radiation Level |

Effective dose range |

| None | 0 |

| Minimal | Less than 0.1 mSv |

| Low | 0.1 – 1.0 mSv |

| Medium | 1.0 – 10 mSv |

| High | 10 – 100 mSv |

| * Adapted from American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria, Radiation Dose Assessment Introduction 2008 | |

These data also demonstrate that you cannot simply use the average relative risk shown in Table 1 to estimate the increased incidence of cancer due to radiation exposure. In order to do this analysis correctly, you need take into consideration the age of all individuals in the irradiated group. For instance, a man of 80 has a life expectancy of about 8 years, versus 33 years for a man of 45. Thus the risk to individuals over the age of 70 is, for all practical purposes, essentially nil. Table 2 illustrates what the American College of Radiology considers minimal to high radiation doses in “absolute” terms.

| Table 3: Average Effective Dose in CT | ||

| Exam | Relative Radiation Level | Range of values (mSv) |

| Head | 0.9 – 4 | |

| Chest (standard) | 4 – 18 | |

| Chest (high resolution, e.g., pulmonary embolism) |

13 – 40 | |

| Abdomen | 3.5 – 25 | |

| Pelvis | 3.3 – 10 | |

| Coronary Angiogram | 5 – 32 | |

| Virtual Colonoscopy | 4 – 13 | |

| Calcium Scoring | 1 – 12 | |

This is why there is an increase in the relative risk values for the “entire population” if children are included in that evaluation. However, even a quick glance at Figure 28 (above), where the estimated lifetime risk that radiation will result in cancer (carcinogenesis) is presented relative to the person’s age, shows that children have a 10% – 15% lifetime risk from radiation exposure, while individuals over the age of 60 have minimal to no risk (due to the latency period for cancer and the person’s life expectancy). The accepted latency period is, by the way ~ 10 years.

Table 1 shows the relative risk of developing cancer per sievert (Sv) unit of radiation exposure. Tables 3 and 4 provide some comparison benchmarks of radiation exposure both in relative terms (low, medium, high) and in terms of common, specific medical imaging procedures used in regional CT.

So, let’s put this information in the context of a cryonicist wishing to reduce his risk of unexpected deanimation. The protocol being proposed here assumes a baseline scan at age 45 for males (50 for females) which, if free of any indication of ongoing morbid processes, is to be repeated in 5 years, at age 51. If than scan is negative, subsequent scans would be performed at intervals of 5 years (if negative) until age 81, at which time the scan interval would decrease to 2 years. If we assume a lifetime cancer risk of approximately 1 in 1000 and a total of 7 scans until age 81, at which point any further risk from radiation exposure becomes irrelevant, we might expect to see an increase in the lifetime risk of cancer from approximate 33% to 34%. Even if the number of scans were more than doubled to 20; one per two years during the interval between age 50 and age 80, the lifetime risk of cancer would increase at most to ~ 35%.[1] This of course, assumes that all DSSs are CT, as opposed to MRI.

|

Table 4: Some Exposure Risks for Comparison |

|

| Activity/Exposure | mSv/year |

| Smoking 30 cigarettes a day | 60–80 |

| New York-Tokyo flights for airline crew | 9 .0 |

| Average radiation dose for Americans | 6.0 |

| Dose from cosmic radiation at sea level: | 0.24 |

These risk calculations are based on the linear no-threshold (LNT) model of radiation risk. This model assumes that the carcinogenicity of radiation is proportional to dose, even down to the lowest levels. No one really knows how carcinogenic low-dose radiation is, because the carcinogenicity of low doses is so small that it’s practically impossible to measure. The official position of the Health Physics Society is that quantitative estimates of risk for doses below 50 mSv per year (100 mSv lifetime) cannot be made.[2]

___________________________________________________

As useful aside, if you are interested in the progress being made in medical imaging, I would highly recommend the blog Magnetic Resonance Imaging: To See and Be Amazed: http://limpeter-mriblog.blogspot.com/ The site contains many beautiful images and is a treasure trove of information on both the mainstream progress, and the esoterica of MRI

_________________________________________________

End of Part 4

[1] This also does not take into consideration the possible brief use of radioprotective nutrients taken prior to the scan.

[2] My thanks to Dr. Brian Wowk, Ph.D. from whom I stole this paragraph.

Selected Bibliography of Sources Consulted on the Medical Ethics of Prophylactic Screening

1: Sarma A, Heilbrun ME. A medical student perspective on self-referral and

overutilization in radiology: application of the four core principles of medical

ethics. J Am Coll Radiol. 2012 Apr;9(4):251-5. PubMed PMID: 22469375.

2: Levin DC, Rao VM. Turf wars in radiology: updated evidence on the relationship

between self-referral and the overutilization of imaging. J Am Coll Radiol. 2008

Jul;5(7):806-10. PubMed PMID: 18585657.

3: Hendee WR, Becker GJ, Borgstede JP, Bosma J, Casarella WJ, Erickson BA,

Maynard CD, Thrall JH, Wallner PE. Addressing overutilization in medical imaging.

Radiology. 2010 Oct;257(1):240-5. Epub 2010 Aug 24. PubMed PMID: 20736333.

4: Kennelly J. Medical ethics: four principles, two decisions, two roles and no

reasons. J Prim Health Care. 2011 Jun 1;3(2):170-4. PubMed PMID: 21625670.

5: Levin DC. The 2005 Robert D. Moreton lecture: the inappropriate utilization of

imaging through self-referral. J Am Coll Radiol. 2006 Feb;3(2):90-5. PubMed PMID:

17412017.

6: Ewart RM. Primum non nocere and the quality of evidence: rethinking the ethics

of screening. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2000 May-Jun;13(3):188-96. Review. PubMed

PMID: 10826867.

7: Magnavita N, Bergamaschi A. Ethical problems in radiology: radiological

consumerism. Radiol Med. 2009 Oct;114(7):1173-81. Epub 2009 Aug 7. PubMed PMID:

19662338.

8: Lebowitz PH. “Stark” reality: self-referral rule holds risk and opportunity.

Radiol Manage. 2001 Sep-Oct;23(5):34-9. PubMed PMID: 11680255.

9: Tangwa GB. Ethical principles in health research and review process. Acta

Trop. 2009 Nov;112 Suppl 1:S2-7. Epub 2009 Aug 7. PubMed PMID: 19665441.

10: Vineis P, Soskolne CL. Cancer risk assessment and management. An ethical

perspective. J Occup Med. 1993 Sep;35(9):902-8. Review. PubMed PMID: 8229342.

11: Ebbesen M, Pedersen BD. Using empirical research to formulate normative

ethical principles in biomedicine. Med Health Care Philos. 2007 Mar;10(1):33-48.

Epub 2006 Sep 6. PubMed PMID: 16955345.

12: Singh A. Ethics for medical educators: an overview and fallacies. Indian J

Psychol Med. 2010 Jul;32(2):83-6. PubMed PMID: 21716861; PubMed Central PMCID:

PMC3122542.

13: Holm S. Not just autonomy–the principles of American biomedical ethics. J

Med Ethics. 1995 Dec;21(6):332-8. PubMed PMID: 8778456; PubMed Central PMCID:

PMC1376829.ral PMCID: PMC3235350.

14: Printz BF. Noninvasive imaging modalities and sudden cardiac arrest in the

young: can they help distinguish subjects with a potentially life-threatening

abnormality from normals? Pediatr Cardiol. 2012 Mar;33(3):439-51. Epub 2012 Feb

14. PubMed PMID: 22331054.

15: Chow A, Drummond KJ. Ethical considerations for normal control subjects in MRI

research. J Clin Neurosci. 2010 Sep;17(9):1111-3. PubMed PMID: 20700948.

4: Puls R, Hamm B, Hosten N. [MRI without radiologists--ethical aspects of

population based studies with MRI imaging]. Rofo. 2010 Jun;182(6):469-71. Epub

2010 Jun 1. German. PubMed PMID: 20517795.

16: Seki A, Uchiyama H, Fukushi T, Sakura O, Tatsuya K; Japan Children’s Study

Group. Incidental findings of brain magnetic resonance imaging study in a

pediatric cohort in Japan and recommendation for a model management protocol. J

Epidemiol. 2010;20 Suppl 2:S498-504. Epub 2010 Feb 23. PubMed PMID: 20179362.

17: Sormani MP. The Will Rogers phenomenon: the effect of different diagnostic

criteria. J Neurol Sci. 2009 Dec;287 Suppl 1:S46-9. PubMed PMID: 20106348.

18: Kouklakis G, Babali A, Gatopoulou A, Lirantzopoulos N, Efremidou E,

Vathikolias K. Asymptomatic brain finding results on MRI in a patient with

Crohn’s disease: a case report. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2009

Dec;18(4):479-81. PubMed PMID: 20076823.

19: Fenton A, Meynell L, Baylis F. Ethical challenges and interpretive

difficulties with non-clinical applications of pediatric FMRI. Am J Bioeth. 2009

Jan;9(1):3-13. PubMed PMID: 19132609.

20: Grainger R, Stuckey S, O’Sullivan R, Davis SR, Ebeling PR, Wluka AE. What is

the clinical and ethical importance of incidental abnormalities found by knee

MRI? Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(1):R18. Epub 2008 Feb 5. PubMed PMID: 18252003;

PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2374445.

21: Ladd SC, Ladd ME. Perspectives for preventive screening with total body MRI.

Eur Radiol. 2007 Nov;17(11):2889-97. Epub 2007 Jun 5. Review. PubMed PMID:

17549492.

22: Illes J, Rosen A, Greicius M, Racine E. Prospects for prediction: ethics

analysis of neuroimaging in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007

Feb;1097:278-95. Review. PubMed PMID: 17413029; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3265384.

23: Illes J, Raffin TA. No child left without a brain scan? Toward a pediatric

neuroethics. Cerebrum. 2005 Summer;7(3):33-46. PubMed PMID: 16619411.

13: Illes J, Kirschen MP, Karetsky K, Kelly M, Saha A, Desmond JE, Raffin TA,

Glover GH, Atlas SW. Discovery and disclosure of incidental findings in

neuroimaging research. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004 Nov;20(5):743-7. PubMed PMID:

15503329; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC1506385.

24: Ustun C, Ceber E. Ethical issues for cancer screenings. Five countries–four

types of cancer. Prev Med. 2004 Aug;39(2):223-9. PubMed PMID: 15226029.

25: Illes J, Rosen AC, Huang L, Goldstein RA, Raffin TA, Swan G, Atlas SW.

Ethical consideration of incidental findings on adult brain MRI in research.

Neurology. 2004 Mar 23;62(6):888-90. PubMed PMID: 15037687; PubMed Central PMCID:

PMC1506751.

26: Ustun C, Ceber E. Ethical issues for cancer screening. Asian Pac J Cancer

Prev. 2003 Aug-Dec;4(4):373-6. PubMed PMID: 14728598.

17: Rosen AC, Bokde AL, Pearl A, Yesavage JA. Ethical, and practical issues in

applying functional imaging to the clinical management of Alzheimer’s disease.

Brain Cogn. 2002 Dec;50(3):498-519. Review. PubMed PMID: 12480493.

27: Illes J, Desmond JE, Huang LF, Raffin TA, Atlas SW. Ethical and practical

considerations in managing incidental findings in functional magnetic resonance

imaging. Brain Cogn. 2002 Dec;50(3):358-65. PubMed PMID: 12480483.

28: Wexler L. Ethical considerations in image-based screening for coronary artery

disease. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2002 Apr;13(2):95-106. Review. PubMed PMID:

12055454.

29: Plevritis SK, Ikeda DM. Ethical issues in contrast-enhanced magnetic

resonance imaging screening for breast cancer. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2002

Apr;13(2):79-84. Review. PubMed PMID: 12055452.

30: Kulczycki J. [Considerations of biopsy in neurological diagnosis]. Neurol

Neurochir Pol. 2001 Sep-Oct;35(5):951-6. Polish. PubMed PMID: 11873607.

31: Victoroff MS. Risky business when public plays doctor with open-access MRI.

Manag Care. 2001 Dec;10(12):50-1. PubMed PMID: 11795003.

32: Alfano B, Brunetti A. Advances in brain imaging: a new ethical challenge. Ann

Ist Super Sanita. 1997;33(4):483-8. Review. PubMed PMID: 9616958.

33: Adams DM, Winslade WJ. Consensus, clinical decision making, and unsettled

cases. J Clin Ethics. 2011 Winter;22(4):310-27. PubMed PMID: 22324212.

34: Huddle TS. MORAL FICTION OR MORAL FACT? THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN DOING ANDALLOWING IN MEDICAL ETHICS. Bioethics. 2012 Feb 2. doi:

10.1111/j.1467-8519.2011.01944.x. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 22296611.

35: Prvulovic D, Hampel H. Ethical considerations of biomarker use in

neurodegenerative diseases–a case study of Alzheimer’s disease. Prog Neurobiol.

2011 Dec;95(4):517-9. Epub 2011 Nov 22. PubMed PMID: 22137044.

36: Hamann J, Bronner K, Margull J, Mendel R, Diehl-Schmid J, Bühner M, Klein R,

Schneider A, Kurz A, Perneczky R. Patient participation in medical and social

decisions in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011 Nov;59(11):2045-52. doi:

10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03661.x. Epub 2011 Oct 22. PubMed PMID: 22092150.

37: Schaefer C, Weissbach L. [Cancer screening: curative or harmful? An ethical

dilemma facing the physician]. Urologe A. 2011 Dec;50(12):1595-9. German. PubMed

PMID: 22009258.

38: Wejda S. [Does a gain in knowledge with no medical consequences trigger

statutory health insurance coverage obligation?]. Z Evid Fortbild Qual

Gesundhwes. 2011;105(7):531-3. Epub 2011 Aug 24. German. PubMed PMID: 21958618.

39: Berlin L. Interpreting radiologic studies obtained months earlier. AJR Am J

Roentgenol. 2011 Sep;197(3):W538. PubMed PMID: 21862786.

40: Rechel B, Kennedy C, McKee M, Rechel B. The Soviet legacy in diagnosis and

treatment: Implications for population health. J Public Health Policy. 2011

Aug;32(3):293-304. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2011.18. Epub 2011 May 12. PubMed PMID:

21808248.

41: Hersch J, Jansen J, Irwig L, Barratt A, Thornton H, Howard K, McCaffery K. How

do we achieve informed choice for women considering breast screening? Prev Med.

2011 Sep 1;53(3):144-6. Epub 2011 Jun 24. PubMed PMID: 21723312.

42: Offit K. Personalized medicine: new genomics, old lessons. Hum Genet. 2011

Jul;130(1):3-14. Epub 2011 Jun 26. Review. PubMed PMID: 21706342; PubMed Central

PMCID: PMC3128266.

43: Arribas-Ayllon M. The ethics of disclosing genetic diagnosis for Alzheimer’s

disease: do we need a new paradigm? Br Med Bull. 2011;100:7-21. Epub 2011 Jun 14.

Review. PubMed PMID: 21672937.

44: Sijmons RH, Van Langen IM, Sijmons JG. A clinical perspective on ethical

issues in genetic testing. Account Res. 2011 May;18(3):148-62. Review. PubMed

PMID: 21574071.

45: Chandrashekhar Y, Narula J. Medical imaging: the new Rosetta stone. JACC

Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011 Apr;4(4):440-3. PubMed PMID: 21492822.

46: Nelson B. Small lesions, big dilemmas: earlier detection creates ethical

questions. Cancer Cytopathol. 2011 Feb 25;119(1):1-2. doi: 10.1002/cncy.20137.

PubMed PMID: 21319307.

47: Licastro F, Caruso C. Predictive diagnostics and personalized medicine for

the prevention of chronic degenerative diseases. Immun Ageing. 2010 Dec 16;7

Suppl 1:S1. PubMed PMID: 21172060; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3024875.

48: Brownsword R, Earnshaw JJ. The ethics of screening for abdominal aortic

aneurysm in men. J Med Ethics. 2010 Dec;36(12):827-30. PubMed PMID: 21112941.

49: Sepucha KR, Fagerlin A, Couper MP, Levin CA, Singer E, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. How

does feeling informed relate to being informed? The DECISIONS survey. Med Decis

Making. 2010 Sep-Oct;30(5 Suppl):77S-84S. PubMed PMID: 20881156.

50: Raskin MM. The perils of communicating the unexpected finding. J Am Coll

Radiol. 2010 Oct;7(10):791-5. PubMed PMID: 20889109.

51: Dudzinski DM, Hébert PC, Foglia MB, Gallagher TH. The disclosure

dilemma–large-scale adverse events. N Engl J Med. 2010 Sep 2;363(10):978-86.

Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2010 Oct 21;363(17):1682. PubMed PMID: 20818911.

52: Laurance J. Ignorance can be preferable? Lancet. 2010 Jun 19;375(9732):2138.

PubMed PMID: 20609941.

53: Stol YH, Menko FH, Westerman MJ, Janssens RM. Informing family members about

a hereditary predisposition to cancer: attitudes and practices among clinical

geneticists. J Med Ethics. 2010 Jul;36(7):391-5. PubMed PMID: 20605992.

54: de Hoop B, Schaefer-Prokop C, Gietema HA, de Jong PA, van Ginneken B, van

Klaveren RJ, Prokop M. Screening for lung cancer with digital chest radiography:

sensitivity and number of secondary work-up CT examinations. Radiology. 2010

May;255(2):629-37. PubMed PMID: 20413773.

55: Shahidi J. Not telling the truth: circumstances leading to concealment of

diagnosis and prognosis from cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2010

Sep;19(5):589-93. Epub 2009 Dec 3. Review. PubMed PMID: 20030693.

56: Toto RD. Screening and evaluation of study subjects in patient-oriented

research. J Investig Med. 2010 Apr;58(4):608-11. PubMed PMID: 20009952.

57: de Jong A, Dondorp WJ, de Die-Smulders CE, Frints SG, de Wert GM.

Non-invasive prenatal testing: ethical issues explored. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010

Mar;18(3):272-7. Epub 2009 Dec 2. PubMed PMID: 19953123; PubMed Central PMCID:

PMC2987207.

58: Toufexis M, Gieron-Korthals M. Early testing for Huntington disease in

children: pros and cons. J Child Neurol. 2010 Apr;25(4):482-4. Epub 2009 Oct 6.

PubMed PMID: 19808987.

59: Ky P, Hameed H, Christo PJ. Independent Medical Examinations: facts and

fallacies. Pain Physician. 2009 Sep-Oct;12(5):811-8. Review. PubMed PMID:

19787008.

60: O’Sullivan E. Withholding truth from patients. Nurs Stand. 2009 Aug

5-11;23(48):35-40. PubMed PMID: 19753871.

61: Karssemeijer N, Bluekens AM, Beijerinck D, Deurenberg JJ, Beekman M, Visser

R, van Engen R, Bartels-Kortland A, Broeders MJ. Breast cancer screening results

5 years after introduction of digital mammography in a population-based screening

program. Radiology. 2009 Nov;253(2):353-8. Epub 2009 Jul 31. PubMed PMID:

19703851.

62: Romano ME, Wahlander SB, Lang BH, Li G, Prager KM. Mandatory ethics

consultation policy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009 Jul;84(7):581-5. PubMed PMID: 19567711;

PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2704129.

63: Burger IM, Kass NE. Screening in the dark: ethical considerations of

providing screening tests to individuals when evidence is insufficient to support

screening populations. Am J Bioeth. 2009 Apr;9(4):3-14. PubMed PMID: 19326299;

PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3115566.

64: Malm H. On patient requests for unproven screening: dim guidance for

screening in the dark. Am J Bioeth. 2009 Apr;9(4):15-7. PubMed PMID: 19326302.

65: Wilfond BS. Policy in the light: professional society guidelines begin the

ethical conversations about screening. Am J Bioeth. 2009 Apr;9(4):17-9. PubMed

PMID: 19326303.

66: Doukas DJ. Professional integrity and screening tests. Am J Bioeth. 2009

Apr;9(4):19-21. PubMed PMID: 19326304.

67: Rosenberg L. Does direct-to-consumer marketing of medical technologies

undermine the physician-patient relationship? Am J Bioeth. 2009 Apr;9(4):22-3.

PubMed PMID: 19326306.

68: Faulkner K. Ethical concerns arising from screening procedures such as

mammography and self-referral. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2009 Jul;135(2):90-4. Epub

2009 Feb 21. PubMed PMID: 19234319.

69: Dunnick NR, Applegate KE, Arenson RL. The inappropriate use of imaging

studies: a report of the 2004 Intersociety Conference. J Am Coll Radiol. 2005

May;2(5):401-6. Review. PubMed PMID: 17411843.

70: Cascade PN. Resolved: that informed consent be obtained before screening CT.

J Am Coll Radiol. 2004 Feb;1(2):82-4. Review. PubMed PMID: 17411529.

71: Lee CI, Forman HP. CT screening for lung cancer: implications on social

responsibility. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007 Feb;188(2):297-8. PubMed PMID:

17242233.

72: Gietema HA, Wang Y, Xu D, van Klaveren RJ, de Koning H, Scholten E,

Verschakelen J, Kohl G, Oudkerk M, Prokop M. Pulmonary nodules detected at lung

cancer screening: interobserver variability of semiautomated volume measurements.

Radiology. 2006 Oct;241(1):251-7. Epub 2006 Aug 14. PubMed PMID: 16908677.

73: Bonneux L. [The unreasonableness of prostate-cancer screening and the ethical

problems pertaining to its investigation]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2005 Apr

30;149(18):966-71. Dutch. PubMed PMID: 15903036.

74: Monaghan C, Begley A. Dementia diagnosis and disclosure: a dilemma in

practice. J Clin Nurs. 2004 Mar;13(3a):22-9. PubMed PMID: 15028035.

75: Swensen SJ, Jett JR, Midthun DE, Hartman TE. Computed tomographic screening

for lung cancer: home run or foul ball? Mayo Clin Proc. 2003 Sep;78(9):1187-8.

PubMed PMID: 12962174.

76: Berlin L. Medicolegal and ethical issues in radiologic screening. Semin

Roentgenol. 2003 Jan;38(1):77-86. Review. PubMed PMID: 12698593.

77: Millett C, Parker M. Informed decision making for cancer screening–not all

of the ethical issues have been considered. Cytopathology. 2003 Feb;14(1):3-4.

PubMed PMID: 12588303.

78: Wexler L. Ethical considerations in image-based screening for coronary artery

disease. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2002 Apr;13(2):95-106. Review. PubMed PMID:

12055454.

79: McQueen MJ. Some ethical and design challenges of screening programs and

screening tests. Clin Chim Acta. 2002 Jan;315(1-2):41-8. Review. PubMed PMID:

11728409.

80: Eysenbach G. Towards ethical guidelines for dealing with unsolicited patient

emails and giving teleadvice in the absence of a pre-existing patient-physician

relationship systematic review and expert survey. J Med Internet Res. 2000

Jan-Mar;2(1):E1. PubMed PMID: 11720920; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC1761847.

81: Gates TJ. Screening for cancer: evaluating the evidence. Am Fam Physician.

2001 Feb 1;63(3):513-22. Review. PubMed PMID: 11272300.

82: Brant-Zawadzki MN. Screening on demand: potent of a revolution in medicine.

Diagn Imaging (San Franc). 2000 Dec;22(12):25-7. PubMed PMID: 11146799.

83: Teichman P. Ethics of screening. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2000

Sep-Oct;13(5):385-6. PubMed PMID: 11001016.

84: Ewart RM. Primum non nocere and the quality of evidence: rethinking the

ethics of screening. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2000 May-Jun;13(3):188-96. Review.

PubMed PMID: 10826867.

85: Forbes K. The diagnosis of dying. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1999

May-Jun;33(3):287. PubMed PMID: 10402585.

86: Törnberg SA. Screening for early detection of cancer–ethical aspects. Acta

Oncol. 1999;38(1):77-81. Review. PubMed PMID: 10090692.

87: Malm HM. Medical screening and the value of early detection. When unwarranted

faith leads to unethical recommendations. Hastings Cent Rep. 1999

Jan-Feb;29(1):26-37. Review. PubMed PMID: 10052009.

Appendix 1

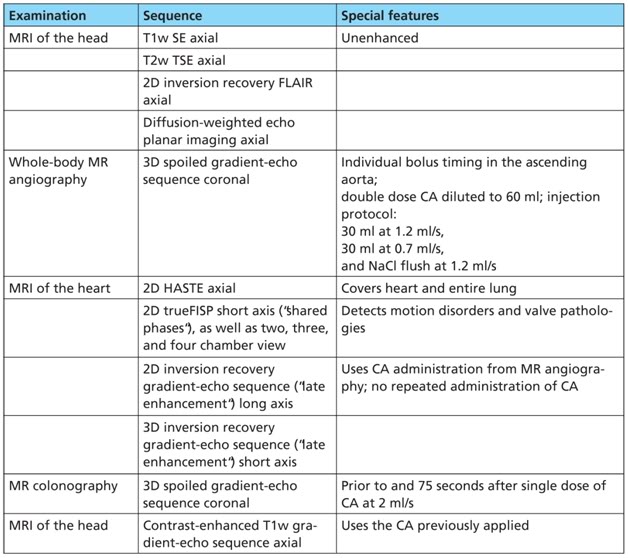

Appendix I: Specimen Protocol for Whole Body MRI Examination to Predict Early Deanimation

Table A-1: Protocol for a whole-body MRI examination for atherosclerosis and colonic polyps. The total examination time (“in-room time ”) is approx. 60 min. SE: spin-echo sequence; TSE: turbo spin echo sequence; CA: contrast agent; FLAIR: fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequence; HASTE: half-Fourier single-shot turbo spin-echo sequence; true FISP: true fast imaging with steady-state precession

A protocol for a comprehensive examination, not only of the vascular system, is presented as follows (Table A-1). Due to the systemic nature of atherosclerosis, a specific screening protocol has to demonstrate high accuracy in the detection of vascular changes over several regions of the body. This includes the cerebrovascular system with its extracerebral and intracerebral arteries, as well as the parenchyma supplied by these vessels. It is really rather difficult to predict cerebrovascular disease; only 26–50% of patients with a peripheral vascular occlusive disease (PVOD) have a cerebral component [79, 80]; many patients with a vascular disease are however only diagnosed once they have become symptomatic [1].

The screening protocol for atherosclerosis also includes the vascular examination of the aorta, supraaortal branches, visceral vessels, and the periphery. The possibility of imaging all these vessels in a single, brief examination has significantly changed the diagnostic procedure in centers having his facility. Finally, the heart should be examined. Even though the examination may often “only” be able to look for wall motion disorders and previous cardiac infarcts for reasons of time pressure or the lack of suitable sequences, even this provides important information, since the rate of unknown cardiac infarcts/unidentified CHD is not inconsiderable [2].

The whole-body MR angiography was performed with the aid of a system-compatible “roller-mounted table platform” (back then the newer systems with integrated whole body image acquisition were not yet available) [3]. This platform allows acquisition of 5–6 three-dimensional angiography data sets following a single administration of contrast agent using the “bolus chase” technique. Besides the possibility of now covering a field of view in excess of 180 cm without repositioning the volunteer, an advantage of this system is the use of surface coils, which, thanks to their higher signal-to-noise ratio, deliver significantly improved image quality compared to the body coil integrated into the scanner.

Heart imaging involves an axial T2-weighted “dark-blood” sequence to produce a morphological overview; this is however extended in the craniocaudal direction to include the entire lung. Images of this type are very sensitive for the detection of focal lung nodules [4].

Functional imaging with fast gradient-echo sequences (T2/T1 contrasts are most informative), as well as late enhancement sequences using inversion recovery sequences to optimize the contrast of infarctions versus healthy myocardium, are acquired in several short and long axis sections. Here, late enhancement imaging uses the intravenous contrast agent previously applied for MR angiography, and repeated administration of contrast agent is not required.

In the last part of the whole-body MRI, attention is then turned to malignomas, and MR colonography is performed. Colon carcinoma, as the second most frequent malignant cause of death after bronchial carcinoma, is the special focus of attention. A three dimensional T1-weighted gradient-echo sequence is acquired following spasmolysis and rectal enema [5].

Appendix References

1. McDaniel MD, Cronenwett JL. Basic data related to the natural history of intermittent claudication. Ann Vasc Surg 1989; 3: 273–7.

2. Lundblad D, Eliasson M. Silent myocardial infarction in women with impaired glucose tolerance: The Northern Sweden MONICA study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2003; 2(1): 9.

3. Goyen M, Quick HH, Debatin JF, et al. Whole body 3D MR angiography using a rolling table platform: initial clinical experience. Radiology 2002; 224: 270–7.

4. Vogt FM, Herborn CU, Hunold P, Lauenstein TC, Schroder T, Debatin JF, Barkhausen J. HASTE MRI versus chest radiography in the detection of pulmonary nodules: comparison with MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004; 183(1): 71–8.

5. Ajaj W, Pelster G, Treichel U, Vogt FM, Debatin JF, Ruehm SG, Lauenstein TC. Dark lumen magnetic resonance colonography: comparison with conventional colonoscopy for the detection of colorectal pathology. Gut 2003; 52(12): 1738–43.

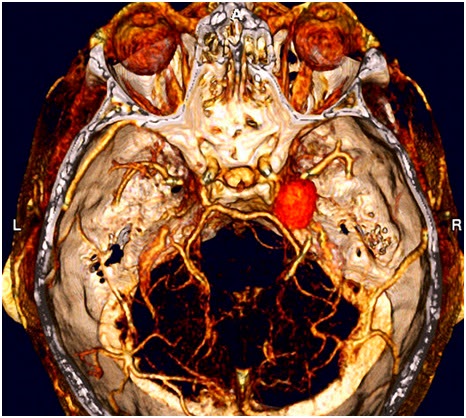

Figure 17: False color CT 3-D reconstruction of a patient’s intracranial arterial vascular tree. The orange-red, cheery shaped anomaly behind the right eye is a large aneurysm. The brain and other intracranial soft tissues have been digitally subtracted to facilitate a complete and unobstructed view of the patient’s arterial vasculature.

Figure 17: False color CT 3-D reconstruction of a patient’s intracranial arterial vascular tree. The orange-red, cheery shaped anomaly behind the right eye is a large aneurysm. The brain and other intracranial soft tissues have been digitally subtracted to facilitate a complete and unobstructed view of the patient’s arterial vasculature.

Figure 20: It was anticipated that the PSA test, used as a screening tool for prostate cancer, would significantly reduce both the morbidity and mortality from the disease. It has so far failed to do so.

Figure 20: It was anticipated that the PSA test, used as a screening tool for prostate cancer, would significantly reduce both the morbidity and mortality from the disease. It has so far failed to do so. Figure 21: The Model 445 Mini-Holter Recorder which was released in 1976 allowed clinicians for the first time to “see” their patients’ ECGs under real-world conditions and for prolonged periods of time.

Figure 21: The Model 445 Mini-Holter Recorder which was released in 1976 allowed clinicians for the first time to “see” their patients’ ECGs under real-world conditions and for prolonged periods of time.

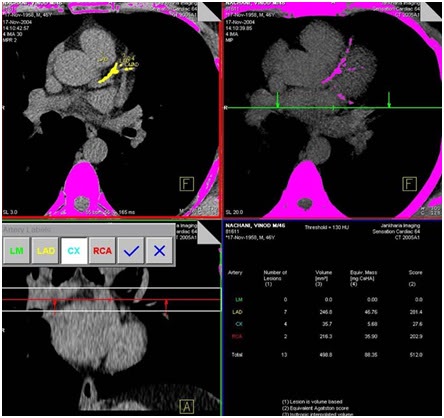

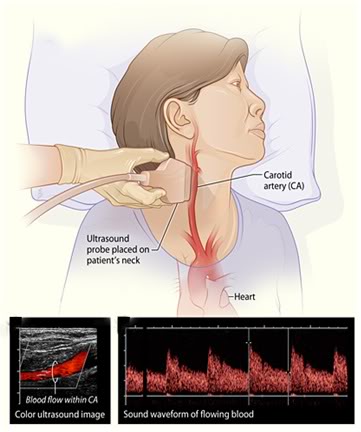

Figure 22: Coronary artery calcium scoring using computed tomography and carotid intima media thickness and plaque using B-mode ultrasonography offer the prospect of detecting almost all coronary artery disease before it reaches the stage where it can cause a heart attack or sudden cardiac arrest.

Figure 22: Coronary artery calcium scoring using computed tomography and carotid intima media thickness and plaque using B-mode ultrasonography offer the prospect of detecting almost all coronary artery disease before it reaches the stage where it can cause a heart attack or sudden cardiac arrest.

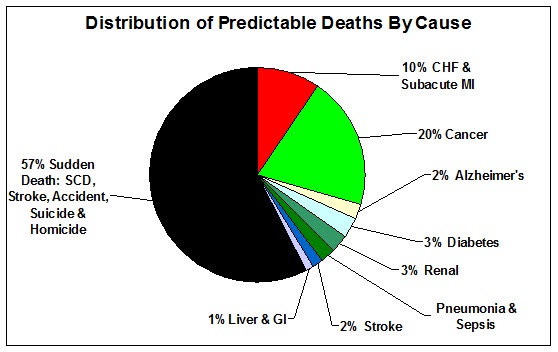

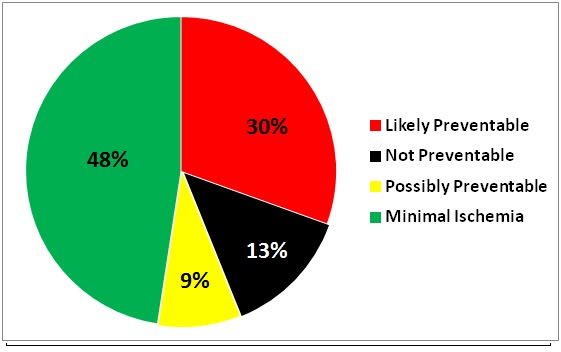

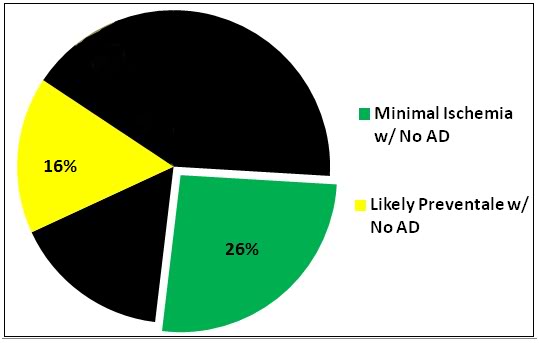

Figure 10: Approximate U.S. distribution of

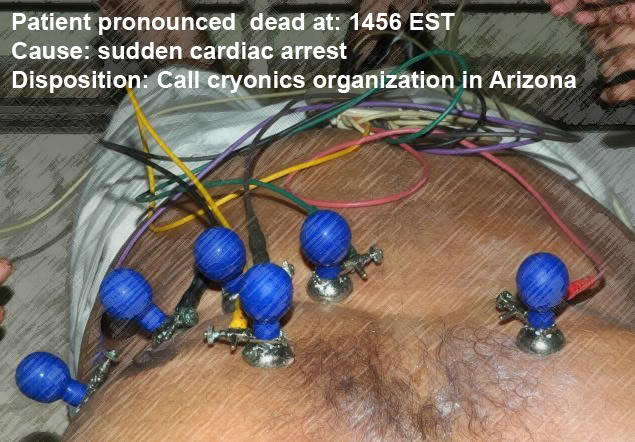

Figure 10: Approximate U.S. distribution of  Figure 11: A major hurdle to evaluating quality in cryonics operations is the lack of any outcomes (e.g., reanimation followed by evaluation) or of any surrogate markers or scoring systems to serve as evaluation tools to determine not only the quality of cryopreservation care being given, but also the objective neurocognitive status of the patients when they enter cryopreservation. For the purposes of this analysis very crude criteria were used to assess the quality of the patient as a finished product at the end of cryopreservation. These were normothermic ischemic time between cardiac arrest and the start of CPS, catastrophic peri-arrest brain injury such as an intracranial bleed followed by prolonged cerebral no-flow before pronouncement of medico-legal death, very long warm ischemic times (> or = to 12 hours) and autopsy.

Figure 11: A major hurdle to evaluating quality in cryonics operations is the lack of any outcomes (e.g., reanimation followed by evaluation) or of any surrogate markers or scoring systems to serve as evaluation tools to determine not only the quality of cryopreservation care being given, but also the objective neurocognitive status of the patients when they enter cryopreservation. For the purposes of this analysis very crude criteria were used to assess the quality of the patient as a finished product at the end of cryopreservation. These were normothermic ischemic time between cardiac arrest and the start of CPS, catastrophic peri-arrest brain injury such as an intracranial bleed followed by prolonged cerebral no-flow before pronouncement of medico-legal death, very long warm ischemic times (> or = to 12 hours) and autopsy.

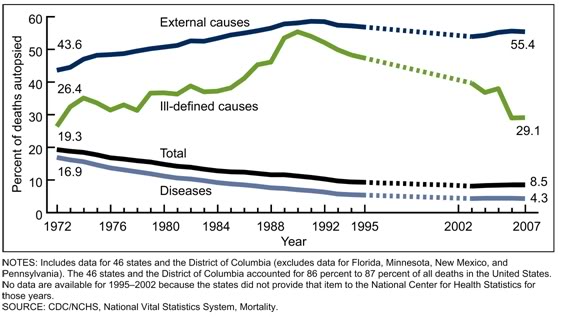

Figure 1: The autopsy rate has declined by half in the United State between 1972 and 2007, although it has shown a slight increase since these data were collected. Source: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db67.pdf

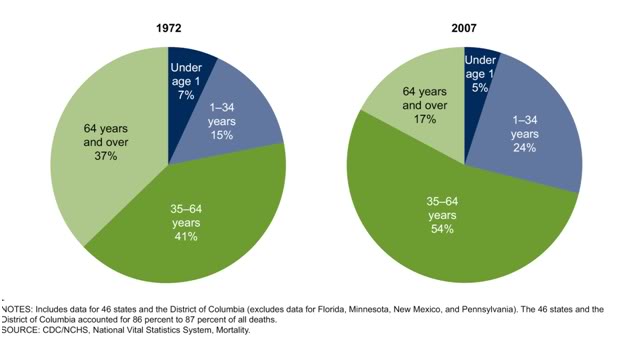

Figure 1: The autopsy rate has declined by half in the United State between 1972 and 2007, although it has shown a slight increase since these data were collected. Source: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db67.pdf Figure 2: Since the first man was cryopreserved in 1967, the demographics of autopsy have shifted increasingly from the aged to those in younger population cohorts. Source: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db67.pdf

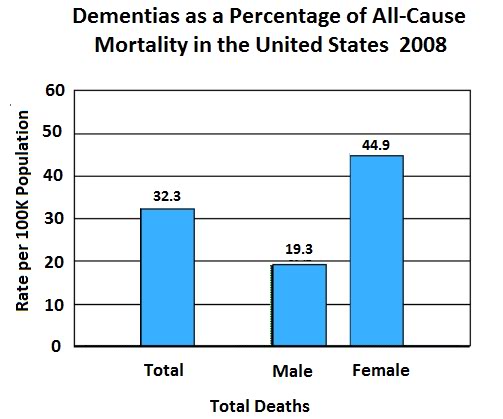

Figure 2: Since the first man was cryopreserved in 1967, the demographics of autopsy have shifted increasingly from the aged to those in younger population cohorts. Source: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db67.pdf Figure 3: Incidence of dementias as a percentage of all cause mortality in males, females and the United States population as a whole. Prepared from data in the National Vital Statistics Report Volume 59, Number 10 December 7, 2011Deaths: Final Data for 2008: 2008http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr59/nvsr59_10.pdf

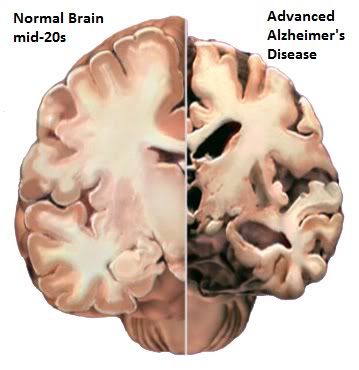

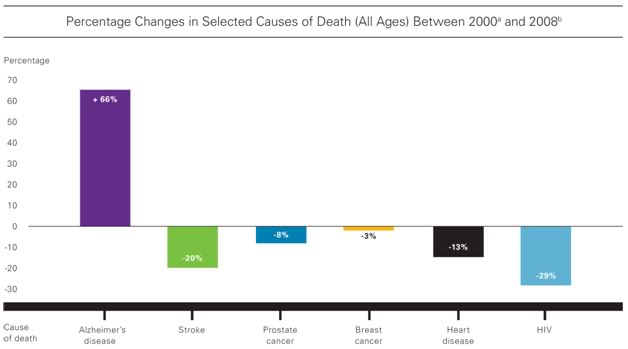

Figure 3: Incidence of dementias as a percentage of all cause mortality in males, females and the United States population as a whole. Prepared from data in the National Vital Statistics Report Volume 59, Number 10 December 7, 2011Deaths: Final Data for 2008: 2008http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr59/nvsr59_10.pdf Figure 4: The large increase in Alzheimer’s Disease as a cause of death in the United States is largely a function of the increasing average age of the population and the survival of many additional individuals into advanced old age. Source: http://www.alz.org/downloads/Facts_Figures_2012.pdf

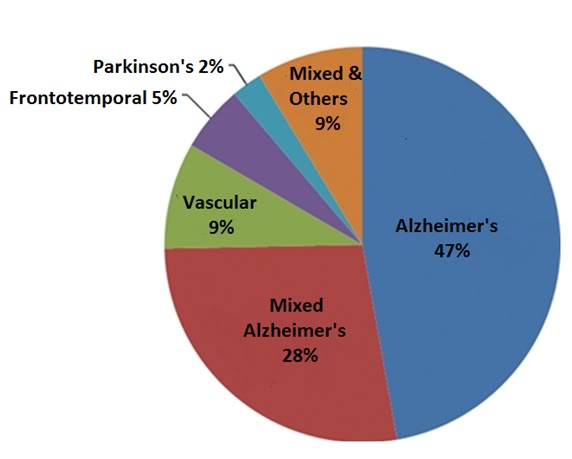

Figure 4: The large increase in Alzheimer’s Disease as a cause of death in the United States is largely a function of the increasing average age of the population and the survival of many additional individuals into advanced old age. Source: http://www.alz.org/downloads/Facts_Figures_2012.pdf Figure 5: A breakdown of dementias by type shows that Alzheimer’s Disease accounts for 47% of the total as the sole cause of the dementia and is a major contributing factor in another 28% making it by far the most common pathological mechanism in play as the cause of dementia in the elderly. [S. Seshadri, S, Wolf, PA, Beiser, A, Au, RU, McNulty, K, White,R, et al. Lifetime risk of dementia and Alzheimer's disease: The impact of mortality on risk estimates in the Framingham Study. Neurology, 49:1498-1504,1997.]

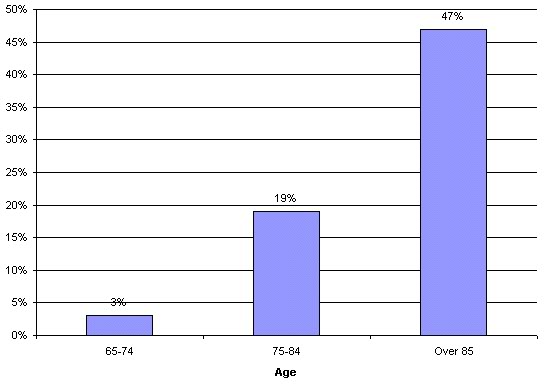

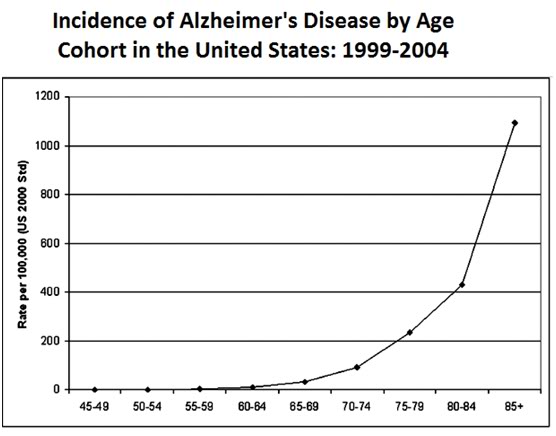

Figure 5: A breakdown of dementias by type shows that Alzheimer’s Disease accounts for 47% of the total as the sole cause of the dementia and is a major contributing factor in another 28% making it by far the most common pathological mechanism in play as the cause of dementia in the elderly. [S. Seshadri, S, Wolf, PA, Beiser, A, Au, RU, McNulty, K, White,R, et al. Lifetime risk of dementia and Alzheimer's disease: The impact of mortality on risk estimates in the Framingham Study. Neurology, 49:1498-1504,1997.] Figure 6: Incidence of Alzheimer’s Disease by age cohort in the US population as of 1988.[ Evans D, et. al. Prevalence of Alzheimer' s Disease in a community population of older persons. JAMA, 262:18;2551-6, 1989.]

Figure 6: Incidence of Alzheimer’s Disease by age cohort in the US population as of 1988.[ Evans D, et. al. Prevalence of Alzheimer' s Disease in a community population of older persons. JAMA, 262:18;2551-6, 1989.] Figure 7: The incidence of Alzheimer’s Disease rises roughly exponentially with age such that over 1,100 people out of 100,000 aged 86 or older have the disease.

Figure 7: The incidence of Alzheimer’s Disease rises roughly exponentially with age such that over 1,100 people out of 100,000 aged 86 or older have the disease. Figure 8: The Siemens Biograph mCT PET is a positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET•CT) scanner that enables precise measurement of metabolic processes and data quantification, including the assessment of neurological disease and malignant tissues (resolution and molecular characterization of neoplasms as small 3 mm in diameter). The device can provide quantitative measurements of brain beta amyloid protein burden.

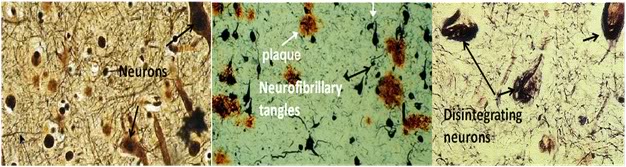

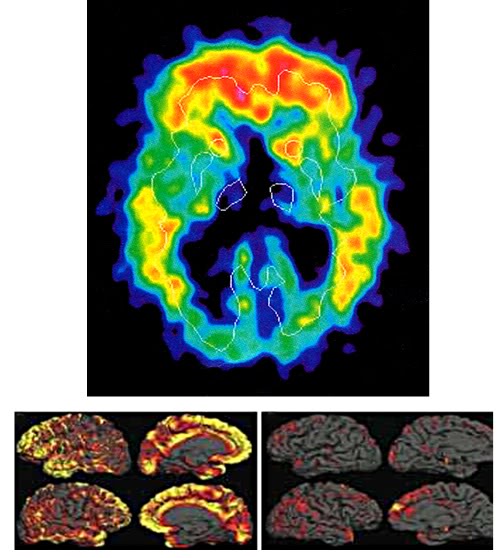

Figure 8: The Siemens Biograph mCT PET is a positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET•CT) scanner that enables precise measurement of metabolic processes and data quantification, including the assessment of neurological disease and malignant tissues (resolution and molecular characterization of neoplasms as small 3 mm in diameter). The device can provide quantitative measurements of brain beta amyloid protein burden. Figure 9: Top: PET scan of beta amyloid deposits in the brain of a patient with early moderate Alzheimer’s disease appear in red in the image above. The beta amyloid deposits are concentrated, as expected, in the frontal and prefrontal cortices as well as in the hippocampus. Bottom: Beta amyloid distribution in the brain of a patient with early moderate AD (L) versus normal control (R). One important consequence of this imaging is the growing realization of the global range of AD’s impact on the brain. As recently as a decade ago it was believed that the destruction of brain tissues was confined largely to the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex, especially early in the disease. It is now understood that the histological destruction of AD is widespread and that during the end-stage of the disease few if any areas can be expected to be spared.

Figure 9: Top: PET scan of beta amyloid deposits in the brain of a patient with early moderate Alzheimer’s disease appear in red in the image above. The beta amyloid deposits are concentrated, as expected, in the frontal and prefrontal cortices as well as in the hippocampus. Bottom: Beta amyloid distribution in the brain of a patient with early moderate AD (L) versus normal control (R). One important consequence of this imaging is the growing realization of the global range of AD’s impact on the brain. As recently as a decade ago it was believed that the destruction of brain tissues was confined largely to the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex, especially early in the disease. It is now understood that the histological destruction of AD is widespread and that during the end-stage of the disease few if any areas can be expected to be spared.

Figure 2: The courtyard of the Hacienda where my dinner companions assailed me over my lack of diligence in having my genotype analyzed to determine my disease risks.

Figure 2: The courtyard of the Hacienda where my dinner companions assailed me over my lack of diligence in having my genotype analyzed to determine my disease risks. Figure 3: The Hacienda on the arid Spanish countryside outside Madrid where we took our repast and discussed singularities, past, present and future.

Figure 3: The Hacienda on the arid Spanish countryside outside Madrid where we took our repast and discussed singularities, past, present and future. But by far my biggest risks, which would not yet (to my knowledge) show up on any genotypic test are Bipolar-2 Disorder and homosexuality, both of which have a devastating impact on longevity, dramatically increasing the risk of a broad range of pathologies, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, dementia, substance abuse, other mental illness, and all cause mortality. My point is that in most cases where genes influence destiny, you’re best clue is the evolved or evolving fate of your kin – unless you are an anonymous orphan, that is.”

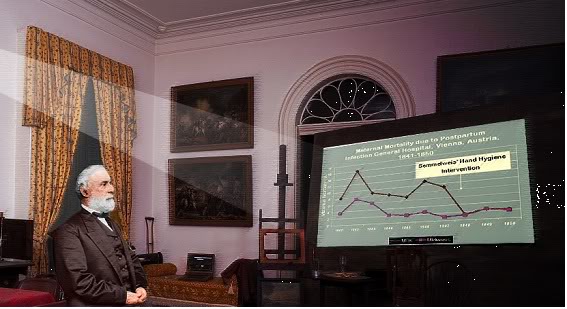

But by far my biggest risks, which would not yet (to my knowledge) show up on any genotypic test are Bipolar-2 Disorder and homosexuality, both of which have a devastating impact on longevity, dramatically increasing the risk of a broad range of pathologies, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, dementia, substance abuse, other mental illness, and all cause mortality. My point is that in most cases where genes influence destiny, you’re best clue is the evolved or evolving fate of your kin – unless you are an anonymous orphan, that is.” Figure 4: President (then General) Robert E. Lee of the Confederate States of America receiving his critical Magic Lantern briefing on the revolutionary, but heretofore unappreciated work of the Hungarian physician Dr. Ignaz Phillip Semmelweis, concerning the importance of antisepsis for the control of infections in battlefield and surgical wounds. The information proved of a vital strategic advantage in helping the Confederacy to successfully prosecute the war against Union forces. Lee is seen here in the sitting room of his home in Arlington, Virginia in this classic painting by John Elder.

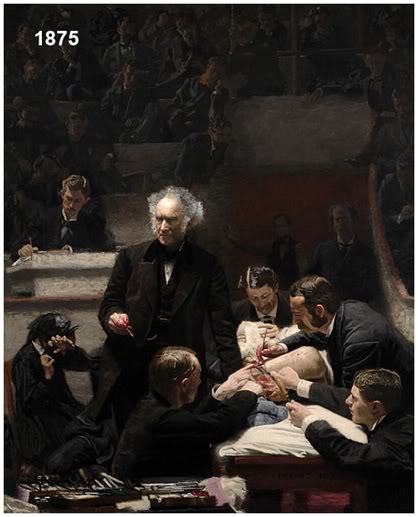

Figure 4: President (then General) Robert E. Lee of the Confederate States of America receiving his critical Magic Lantern briefing on the revolutionary, but heretofore unappreciated work of the Hungarian physician Dr. Ignaz Phillip Semmelweis, concerning the importance of antisepsis for the control of infections in battlefield and surgical wounds. The information proved of a vital strategic advantage in helping the Confederacy to successfully prosecute the war against Union forces. Lee is seen here in the sitting room of his home in Arlington, Virginia in this classic painting by John Elder. Figure 5: In his magnificent painting entitled The Gross Clinic, Thomas Eakins graphically captures the state of surgery in the US during the decades following the US Civil War. These grotesquely unsanitary conditions had by this time to a large extent become a thing of the past in surgical theaters through much of Europe.

Figure 5: In his magnificent painting entitled The Gross Clinic, Thomas Eakins graphically captures the state of surgery in the US during the decades following the US Civil War. These grotesquely unsanitary conditions had by this time to a large extent become a thing of the past in surgical theaters through much of Europe.

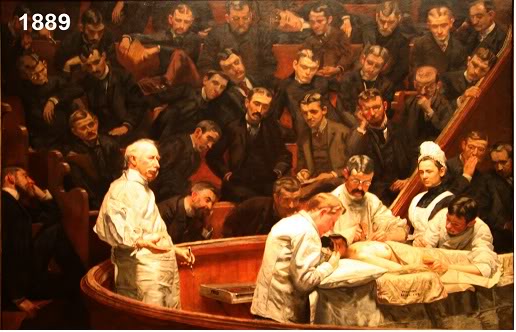

Figure 5: Edward Tenner’s excellent book,

Figure 5: Edward Tenner’s excellent book,

Robert Ettinger (left).

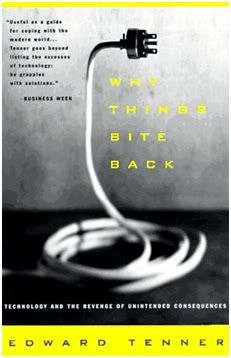

Robert Ettinger (left). The problem to be solved being not the clutter, nor the barrier to tasteful decorating, nor to efficient housekeeping, but rather, the problem of how to make their number start decreasing, rather than increasing. That is, decreasing by some expedient other than by gathering them up into a digital dustbin where they are granted increasingly smaller and smaller and smaller access to the living human eye, as time goes by.

The problem to be solved being not the clutter, nor the barrier to tasteful decorating, nor to efficient housekeeping, but rather, the problem of how to make their number start decreasing, rather than increasing. That is, decreasing by some expedient other than by gathering them up into a digital dustbin where they are granted increasingly smaller and smaller and smaller access to the living human eye, as time goes by.

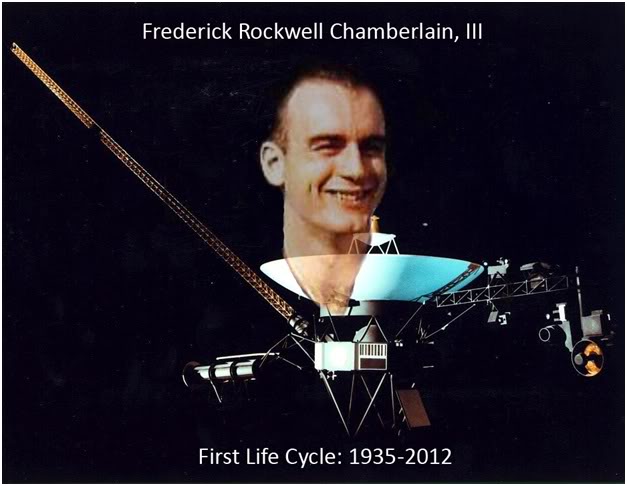

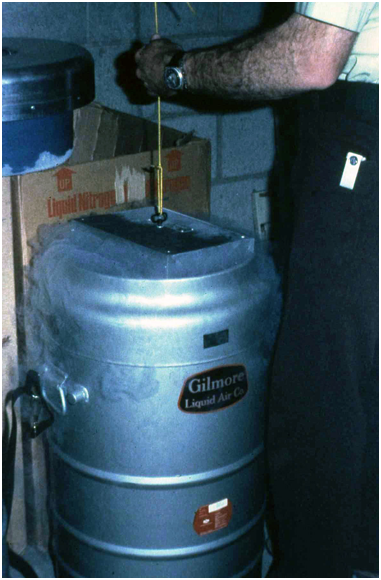

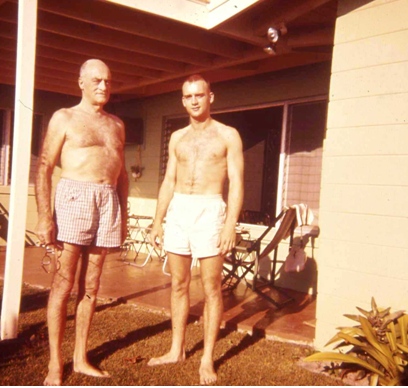

Fred (left) cryopreserving his own father, Fred Jr., in 1976.

Fred (left) cryopreserving his own father, Fred Jr., in 1976. Fred Chamberlain III recently had his brain placed into cryostasis at the Alcor Life Extension Foundation in Scottsdale. His physical presence will be missed by many friends, biological family and chosen family until technology allows a future instantiation to be with us once again.

Fred Chamberlain III recently had his brain placed into cryostasis at the Alcor Life Extension Foundation in Scottsdale. His physical presence will be missed by many friends, biological family and chosen family until technology allows a future instantiation to be with us once again. Here we see Fred in his thirties, sitting on the rim of the Grand Canyon. He was an engineer at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Southern California, where he worked on the Voyager missions to Jupiter and other fascinating projects.

Here we see Fred in his thirties, sitting on the rim of the Grand Canyon. He was an engineer at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Southern California, where he worked on the Voyager missions to Jupiter and other fascinating projects. That’s when I first met and fell in love with him. One of our great intellectual and emotional bonds was our interest in technological means of extending life. Fred and I incorporated the Alcor Life Extension Foundation in 1972; the

That’s when I first met and fell in love with him. One of our great intellectual and emotional bonds was our interest in technological means of extending life. Fred and I incorporated the Alcor Life Extension Foundation in 1972; the

The picture on the left shows us in 2002 when we renewed our

The picture on the left shows us in 2002 when we renewed our

Will she and all the other dead be

Will she and all the other dead be