By Mike Darwin

Figure 1: Cryonics, a bridge to tomorrow, or snow choked catastrophe in the making?

Failure: What is the Really Big Risk?

What I have had to say in the four articles in this series to date has been almost exclusively failure analysis, or put less delicately, criticism. While good criticism isn’t easy, it is unarguably a lot easier than proposing solutions, and more importantly, solutions that are at least worthy of consideration, if not demonstrably practical. The inevitable first response that occurs when a course action other than the one those currently (and for a long time now) in control of cryonics organizations are committed to is to say, “That’s all very and good, but we can’t afford it! We are barely making ends meet now, and we constantly have to increase charges to members and beg for more money.”

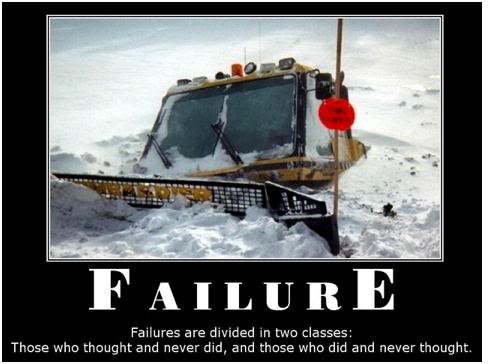

Thus, before considering existential risks and other positive changes in priorities in detail, I will need to consider other more mundane, but likely much more serious risks to the failure of cryonics, some of which appear to be upon us, or nearly so, even as I write these words. Because we never undertook any serious and systematic risk analysis for failure in cryonics we now find ourselves confronting the most common and the most mundane risk of failure of all: organizational failure. Most new business undertakings, regardless of whether they are profit or nonprofit, tax exempt charities or hard driven efforts to make a large financial gain, fail within the first 5-10 years of start-up. Viewed in this light, the “high” failure rate of the relatively (and absolutely) very small number of cryonics enterprises that have existed over the years is not extraordinary; it is par for the course (Figure 2).

Figure 2: While it is well known that most start-up businesses fail, the uniformity of that failure is generally under-appreciated by members of the general public. Historically the rate of start-up failure in the US has been in the range of 98%, however, since the 1940s this has declined to ~5% of all new business enterprises.[1]

Figure 2: While it is well known that most start-up businesses fail, the uniformity of that failure is generally under-appreciated by members of the general public. Historically the rate of start-up failure in the US has been in the range of 98%, however, since the 1940s this has declined to ~5% of all new business enterprises.[1]

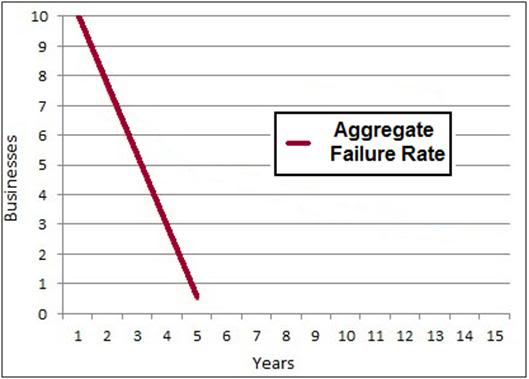

What is assumed is that after this brief initial period of high mortality, businesses that do survive experience a far lower failure rate. This is, in fact correct; those few enterprises that survive gradually absorb the market sector and human and capital resources of the many who fail. However, as can be seen in Figure 3, if we “re-set” the graph at 5 years, and then follow the remaining cohort of enterprises out to the 10 year mark, the mortality rate is still quite high with only 29% of businesses surviving.

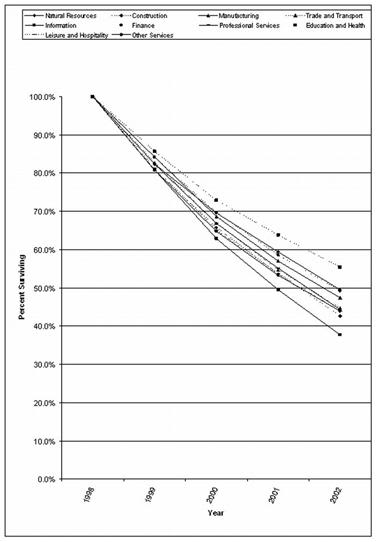

Figure 3: Failure rate of start-up businesses in the US over the ten year period from 1992 to 2002.[2]

Figure 3: Failure rate of start-up businesses in the US over the ten year period from 1992 to 2002.[2]

There is also surprisingly little spread between business types in terms of 10 year survival as can be seen in Figure 4; the difference between sectors is ~ 20%.The shortest surviving businesses are those offering leisure and travel services and the longest surviving are those engaged in providing education and health; with manufacturing falling about midway between these two.

While the general public may not have a good grasp of these numbers with precision, it would strain credibility to assert that they do not have a general feel for the volatility and the short lifespan of most business enterprises. In fact, the older and more experienced the individual is, the more reasonable it would be to assume that his understanding of the ephemeral nature of enterprise is improved. It is thus quite possible, if not likely, that an underlying reason for the lack of credibility of cryonics in that segment of the population most likely to find it desirable is that that same cohort has the most experience with and understanding of the improbability of the very long term (i.e., 100-200 years) survival of any human enterprise. As many scholars and pundits alike have noted, with the exception of the Roman Catholic and various branches of the Orthodox Church, few if any institutions have continuously endured for millenia. Similarly, institutions that have endured for may centuries, such as universities (Oxford and Cambridge come to mind) are typically creatures of nation-states – the other class of entities that have shown endurance in the millennial range. In short, corporations, including NPOs, are almost exclusively short lived creatures that fill a market niche, do their business and then die.

In 2009, the Japanese business analysis and survey firm Tokyo Shoko Research (a combination of Dunn and Bradstreet and TRW in Japan), conducted an examination of the founding dates of the 1,975,620 enterprises in their database.They found 21,666 companies which have existed for over 100 years. The Bank of Korea conducted a similar evaluation of their database and found that there are 3,146 firms founded over 200 years ago in Japan, 837 in Germany, 222 in the Netherlands and 196 in France. There are 7 companies in Japan over 1,000 years old; 89.4% of the companies with over 100 years of history are for profit businesses. However, a closer examination of the history of these long-surviving enterprises reveals that many underwent takeovers, buyouts and essentially a complete restructuring of mission and the nature of the business the firms were engaged in – often more than once in their history. Thus, the chances of a business entity (excluding religious and academic institutions) surviving for >100 years is 1.096%.

.  Figure 4: Survival of business enterprises in the US by type of business.[2]

Figure 4: Survival of business enterprises in the US by type of business.[2]

In recent years there has been increased attention paid to why businesses experience such a high failure rate, and in particular why the early mortality is so punishingly high.. There have been a number of academic studies, as well as a variety of failure analysis books written by businessmen and assorted “consultants” and “gurus” offering tip and techniques for avoiding failure.[3-5]

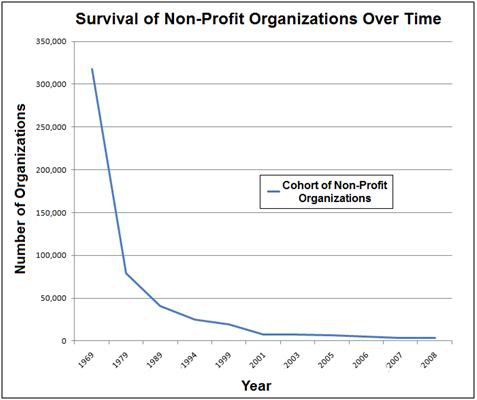

Of considerably more relevance is how 501c3 non-profit organizations fare over time. Figure 5 shows the aggregate survival of non-profit organizations (NPOs) as a cohort from 1969 to 2008, a period of nearkly 40 years. Whilst the early mortality rate is high, it is not nearly as high as is the case for for-profit organizations. NPOs experience heavy mortality over the first decade, with the rate of failure slowing considerably over the second decade of life. However, by the 30 year mark, ~95% of NPOs have failed. The data presented in Figure 5 are probably unrepresentative of what lies ahead for US 501c3 NPOs in the near future, because the number of these organizations has grown from 464,138 in 1989 to 819,008 in 2000 – a doubling in a little over a decade. Not surprisingly, the high rate of failure amongst NPOs is now occurring in part because of the current severe economic Recession, but also because of the entry into the NPO marketplace of a broader cross-section of the population with less experience in the founding and operation of charitable organizations, or indeed businesses of any kind.[3]

Figure 5: Survival of US 501c3 non-profit organizations (aggregate) from 1969 to 2008.[6]

Figure 5: Survival of US 501c3 non-profit organizations (aggregate) from 1969 to 2008.[6]

Many reasons exist for the high mortality rate in businesses both initially and over time. There are many “top 10,” “top 7” and” top 5″ lists of reasons given by various pundits and advisers. In the case of NPOs, some of the most commonly cited causes are shown in Table 1.

Consistently near the top of most lists of reasons for the failure of NPOs are dysfunctional management and failure to maintain and file adequate financial records. In recent years there has also been increasing focus on the criticality of the NPOs’ boards of directors to the success or failure of the organizations.[3, 7-9] In 2003 Judith Miller reported on her extensive longitudinal study of the boards of 12 non-profit organizations. She discovered that there were two primary factors that determined how effective NPO directors were at discharging their duty to monitor and intervene in the action of their NPO. The first of these factors was how the individual board members defined their relationship with the CEO and how well and how well they understood the scope of their monitoring function. Her findings also demonstrated that, given ambiguous rules of accountability and unclear measures of performance, NPO board members tend to monitor in ways that reflect their professional or personal competencies, rather than paying attention to measures that actually indicate progress toward the mission-related goals and initiatives of the organization; and thus of its success or failure. And of course, the degree of commitment and the seriousness with which the directors undertook their monitoring function was also critical.[9]

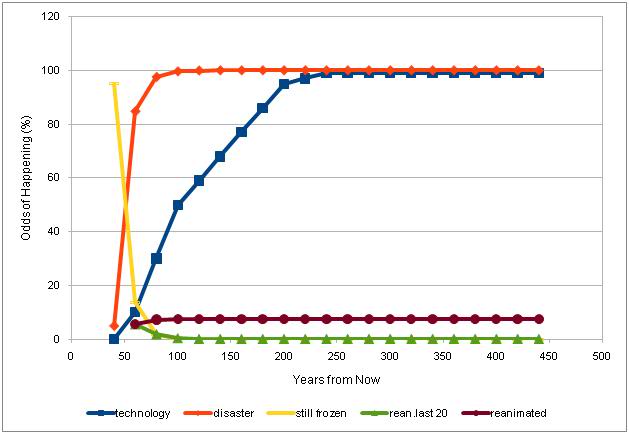

Figure 6: Using the “Cryonics Calculator” developed by Brook Norton (http://www.cryonicscalculator.com/), and assuming a very conservative risk of organizational failure of 30% for the first two decades of cryopreservation, 75% for the second 20 year interval, 10% for the third 20 year interval, 3% for the fourth 20 year interval and 2% for last 20 year interval the probability of being recovered from cryopreservation is only 17%. [This assumes that you are currently 50 years old and will be cryopreserved at age 90 and that you have a 5% risk of autopsy, or other catastrophic destruction of your remains prior to cryopreservation.]

Figure 6: Using the “Cryonics Calculator” developed by Brook Norton (http://www.cryonicscalculator.com/), and assuming a very conservative risk of organizational failure of 30% for the first two decades of cryopreservation, 75% for the second 20 year interval, 10% for the third 20 year interval, 3% for the fourth 20 year interval and 2% for last 20 year interval the probability of being recovered from cryopreservation is only 17%. [This assumes that you are currently 50 years old and will be cryopreserved at age 90 and that you have a 5% risk of autopsy, or other catastrophic destruction of your remains prior to cryopreservation.]

Using a very simple model of the impact of institutional failure on the chances of recovery from cryopreservation and (approximately) applying the historical NPO failure rate data shown in Figure 5, the chances that a person will be recovered from cryopreservation over a 100 year period of storage are only 8%. This outcome does not consider other risks, such as government proscription of cryonics or existential risks such as fire, flood, earthquake, pandemic disease, etc. Very importantly, it does not take into account the probability that existing cryopreservation procedures may not be sufficiently advanced to allow for recovery of today’s patients (the default assigned autopsy risk is 5%, which is also quite low). Given such a high probability of failure solely from lack of institutional continuity, it should be clear why so many people, especially those who are knowledgeable and world-wise, fail to find cryonics sufficiently attractive to commit to it personally.

Money

One conclusion which may be drawn from the above is that cryonics organizations must have “Übercredibility” in every area of their operations where it is possible for them to do so. Certainly Cryonics hasn’t been a commercial success as a “fee for services” operation. There is no large queue of clients or customers waiting at the door, cash in hand, asking to be cryopreserved. The market is and has been microscopic relative to the ~57 million people who die each year on this planet. A simple summing up of the number of cryonics organization and the yearly “service fees” of various kinds they collect from their members yields a dismal number. That dollar amount for the Alcor Life Extension Foundation for the fiscal years 1990 to 2007 would come to only ~ $2,790,997.00. Over 17 years that works out to a paltry $164,176 per year. Whilst that would provide a handsome salary for the two employees at the Cryonics Institute (CI) (and likely cover all of their ancillary operating expenses not paid by patients), it would hardly suffice to pay for the number of employees Alcor has had since at least 1990, when there were 4 full-time employees being paid from the General Operating Fund (there are currently 9 full-time employees and Alcor is advertising for a tenth)..

Fundamental Financial Accountability

Repeated requests by a number of individuals have failed to elicit annual (or any other) comprehensive financial reports for the fiscal years 2006 and 2008-2010. Additionally, the 2005 Financial Statement is available only as a draft, not as the completed, certified document.  Figure 8: Failure to maintain financial accountability and to file the required government paperwork to preserve the corporate shield and to maintain tax exempt status is an indication that an organization may have become terminally dysfunctional.

Figure 8: Failure to maintain financial accountability and to file the required government paperwork to preserve the corporate shield and to maintain tax exempt status is an indication that an organization may have become terminally dysfunctional.

When corporations, large or small, cease to maintain proper financial accounting, as well as transparency and accountability to their shareholders or their members, they are signaling to the world that they are about to become, or have become terminally mismanaged. The failure to maintain and produce federally and state required financial records speaks not just to the dysfunction of the chief financial officer (CFO) and chief executive officer (CEO), but to the board of directors and the entire management team. If such lack of accountability is allowed to persist over a period of years, it may fairly be said that the members or stakeholders are also remiss by failing to demand not only financial accountability from management, but for jeopardizing the tax exempt status and the corporate shield of the organization as well.

————————————————————————————-

NOTE: In the comments section follwing this article, Alcor President and CEO Max More states that,” the (Alcor) 2008 and 2009 financial statements are complete and should be issued by the accounting firm ready to put on Alcor’s website around the end of July.” Max More, Steve Bridge and others also pointed out errors and oversights on my part relating to Alcor’s 990 Report status with the IRS. I have endeavored to correct these problems by editing this article and apologizing for any inconvenience.

————————————————————————————–

Graphic History of the Alcor Life Extension Foundation’s Financial and Membership Growth from 1984-2007

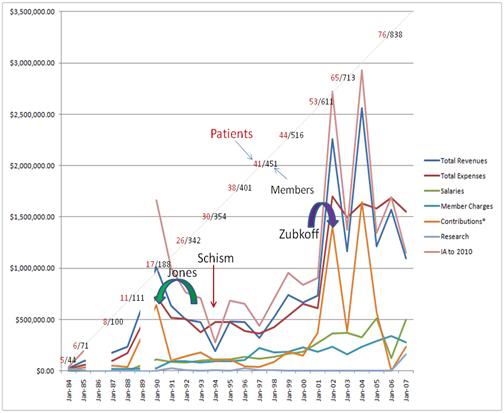

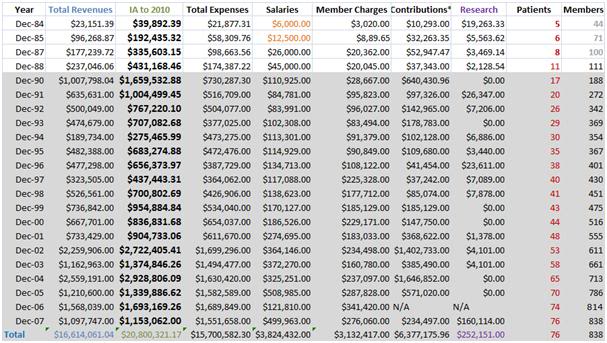

Figure 9: A graphic (incomplete) financial history of the Alcor Life Extension Foundation. Reasonably complete and consecutive data are available for the years 1987 to 2007. The two largest (known) bequests by cryopreservation patients are indicated by the large green and purple colored arrows. Money from the Jones estate began to flow into Alcor in 1988 (green arrow) and from the Zubkoff estate in 2001(purple arrow). Periods for which no data are available (1985-1987 and 1988-1990) appear as blank spaces on the graph. Because Alcor has used a variety of methods of charging members for services, ranging from Cryonics magazine to cryopreservation itself, all charges for member services such as dues and emergency responsibility fees have been consolidated into a single category, “Member Charges.” Similarly, all member Contributions, including those from bequests and directed donations have been combined under the heading of contributions. “Total Revenues” have been shown as inflation adjusted (year by year) under the heading of ÏA.”Inflation Adjustments” (IA) were carried out using “The Inflation Calculator: http://www.westegg.com/inflation/,which employs the Statistical Abstracts of the United States as its source for inflation adjustment data. Research expenditures are essentially invisible in this graph because, after 1989, Alcor spent very little on research with the exception of fiscal year2007. Tabular data for the graph above are present in Table 2.The number of Alcor Members (black print) and patients (red print) are shown at ~ 2 year intervals from 1984 to 2007 as indicated by the blue arrows. The sharp dip in revenues, expenses and contributions which takes place between ~1993 and 1994 represents the period during which Alcor underwent schism (red arrow).

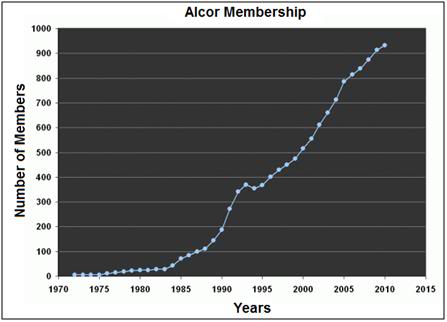

When Alcor was a tiny organization with total annual revenues of less than $30,000, financial reports were prepared monthly and annual financial reports we completed and mailed to members and to all subscribers of Cryonics magazine, typically no later than the February or March following the end of the calendar year (which was also the fiscal year) ending on 31December. This level of accountability was achieved even though Alcor had no money to pay bookkeepers or accountants. Alcor’s last Form 990, which was for the fiscal year of 2009 and which was filed on 14 June, 2011 indicates that Alcor’s total assets were $9,362,293.00 (as of the end of that fiscal year).Prior to the filing of the 2009 Form 990, Alcor made a public announcement that it had received a bequest of ~ $7 million from a member who was recently cryopreserved, which is to be divided equally between the Patient Care Trust and an Endowment Fund, the latter of which is to have a maximum legally allowed annual distribution of 2% per year ($70 K/yr).[12] Thus on no account can financial hardship be an element in this failure to account. Additionally, Alcor has 9 paid full time staff members, including a full time finance director (Bonnie Magee) as well one full time volunteer.[13] As of 2009, its CEO was paid $88,819.00; a respectable sum for an organization with only 913 members and 87 patients in storage.

Table 2: Some of Alcor’s Financial parameters from 1984-2007

The data contained in the area shaded in gray are those that were obtained from formal, year-end comprehensive reports. Other data were obtained from year-end accounting summaries given to Alcor Directors at monthly meetings. Data for 1984 and 1987 are approximate (taken from a graph). “Contributions” for the purpose of this table consists of all funds given by living members as well as those given by bequest, including directed donations that supported Alcor’s non-patient care operations. Monies for long term care of patients and directed donations to the Patient Care Fund (now the Patient Care Trust) are excluded from consideration here. The source for yearly membership and patient numbers was the Alcor website.

The data contained in the area shaded in gray are those that were obtained from formal, year-end comprehensive reports. Other data were obtained from year-end accounting summaries given to Alcor Directors at monthly meetings. Data for 1984 and 1987 are approximate (taken from a graph). “Contributions” for the purpose of this table consists of all funds given by living members as well as those given by bequest, including directed donations that supported Alcor’s non-patient care operations. Monies for long term care of patients and directed donations to the Patient Care Fund (now the Patient Care Trust) are excluded from consideration here. The source for yearly membership and patient numbers was the Alcor website.

Alcor did not get its first employee until July of 1984 and the salary for this employee was paid directly to the employee by the donor until payroll capability was put in place in 1986.

A cursory examination of Alcor’s finances over the past 17 years, from 1990-2007 (data past 2007 are not available from Alcor) reveals some remarkable things. Adjusted for inflation (to 2010 dollars) Alcor has averaged an income of ~ $1,224,000.00 per year, or ~ $20,800,321 over those 17 years. Again, crudely adjusted for inflation Alcor spent ~ $289,973.00 of that ~$21 million in income on research, of which $160,114 (of the total expended on research) was disbursed in a single year (2007); in other words, 1.39%. In 4 of those 17 years the annual expenditure for research was zero.[1] However, it should noted that in both 1989 and 1990 virtually all of Alcor’s resources above those required for basic operations were necessarily committed to fight the numerous legal battles that resulted from an attempt by the state of California to outlaw the practice of cryonics.[14] Table 2 shows selected financial parameters from Alcor’s annual financial reports/statements for the years 1984- 1985 and 1987-1988 (the financial report for fiscal year 1986 is not available) and from 1990-2007.

Where’s the Beef?

When I began this analysis I had no Alcor financial data prior to 1990. After acquiring the data prior to that time in a piecemeal fashion from several resources, I added it to the spreadsheet (Table 2) but decided not to include it in the analysis of the data from 1990-2007 for several reasons; principally because 1990 is the year that the large influx of money from the Jones estate bequest had begun to dramatically transform Alcor, and it is also the year that Alcor’s new management philosophy became manifest.[15-17][i]

During this period Alcor grew from 188 members and 17 patients in cryopreservation to 838 members and 76 patients in cryopreservation. Employee compensation started to rise precipitously beginning ~ 2000, and by ~2007 it totaled ~ $500,000/yr (not adjusted for inflation). For the last year for which there are data available (2007) Alcor had year-end net assets of $103,317 and $339,052 of cash, or cash equivalents on hand. This practice of spending almost all of Alcor’s yearly revenues was not unusual. Despite a highly variable, but overall increasing revenue stream, Alcor consistently spent almost all available income, and in 2005, exceeded it. In examining the financial reports of Alcor there is no evidence of sinking funds, or other mechanisms of cash cushions to deal with the inherently erratic nature of NPO contributed income, or for major unexpected expenses such as litigation, equipment failure, publicity which adversely impacts income, or other kinds of man-made or natural calamities.

Financial records for the decade of 1972 to 1982 are apparently no longer available and may no longer exist. I was unable to locate complete financial reports for the years 1983 and 1989, although I have a number of monthly financial reports from these two years. In October of 1981 Alcor and the Institute for Advanced Biological Studies, Inc., (IABS) merged.[18] From the interval of ~ 1979 to September of 1981 Alcor was almost completely inactive; its sole patient and its member services, including patient storage, were contracted out to Trans Time, Inc., (cryopreservation services) and IABS (monthly magazine). The merger effectively transferred the human, financial and administrative resources of IABS to Alcor and marked the beginning of a fundamentally new and different organization from either IABS, or the pre-merger Alcor. Alcor did not get its first employee until July of 1984.[19] It would thus be of great interest to evaluate the financial history if Alcor from the period of 10/1981 through the end of fiscal year 1989.

As of this writing, the closest it is possible for me to come in determining the financial status of Alcor from the period of 10/82 through the end of fiscal year 1989 is to refer to a graph of Alcor yearly revenues that was prepared for in-house use sometime in 1990. Based on that graph, a rough estimate of Alcor revenues for 1982 was ~ $3,000, for 1983 ~ $13,500 and for ~ $1989 it was $320,000. Thus, a very rough summing up of Alcor’s total revenues for the period from 10/82 through 12/31/1989, adjusted for inflation to 2010 dollars, would be $1,167,595, or $ 194,599 per year. In other words, Alcor’s 6 year averaged yearly revenues for that period were ~5.61% of its averaged annual revenues for the period of 1990-2007.

[1] No detailed accounting is available for fiscal year 2005; the financial data for that year which was used to prepare Figure 7 and Table II were obtained from Alcor’s Form 990 filing with the IRS.

[i] While there were major changes to management structure in 1988, the Dora Kent and DHS litigation consumed almost all of Alcor’s time, attention and resources until early 1990. Once these matters were resolved the new management’s next focus was to initiate litigation against the California Attorney General seeking to allow Dr. Thomas K. Donaldson to be cryopreserved prior to medico-legal death because he was dying from an incurable malignant brain tumor that threatened to seriously (and irreversibly) damage or destroy his brain prior to medico-legal death.

References

1. Knaup A: Survival and longevity in business employment dynamics data: http://www.bls.gov/osmr/pdf/st060040.pdf. Monthly Labor Review 2005.(May):50-56.

2. Shane S: The Illusions of Entrepreneurship: The Costly Myths That Entrepreneurs, Investors, and Policy Makers Live By: Yale University Press; 2008.

3. Powell W, Steinberg, R.: The Nonprofit Sector: A Research Handbook. In., 2nd Edition edn: Yale University Press; 2006.

4. Keough D: The Ten Commandments for Business Failure. New Yoek: Penguin; 2008.

5. Muehlhausen J: The 51 Fatal Business Errors and How to Avoid Them, 3rd edition edn: Mulekick Publishing; 2008.

6. IRS: Data Source: IRS Business Master File, 2011. 2011.

7. Middleton M: Nonprofit Boards of Directors: Beyond the Governance Function. New Haven: Yale University; 1987.

8. Oster SM: Strategic Management for Nonprofit Organizations: Theory and Cases. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995.

9. Miller J: The Board as Monitor of Organizational Activity: The Applicability of Agency Theory to Nonprofit Boards,. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 2002, 12(4):429-450.

10. IRS: 501. Exemption from tax on corporations, certain trusts, etc: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/26/usc_sec_26_00000501—-000-.html. 2010.

11. Brzezinski Z: Out of Control: Global Turmoil on the Eve of the Twenty-first Century. New York: Prentice Hall & IBD; 1994.

12. Alcor Gratefully Receives Large Bequest: http://www.alcor.org/blog/?p=1432

13. Alcor Staff: http://www.alcor.org/AboutAlcor/meetalcorstaff.html

14. Perry R: Alcor’s Legal Battles: http://www.alcor.org/Library/html/legalbattles.html. Cryonics 1999, 1st Quarter.

15. Mondragon C: A New Era Begins: http://www.alcor.org/cryonics/cryonics9301.pdf. Cryonics 1993, 14(1):10-15.

16. Mondragón C: A Stunning Legal Victory for Alcor. Cryonics 1990, 3(7).

17. Darwin M: Thomas Donaldson Files Lawsuit. Cryonics 1990, 11(6):2.

18. Staff: IABS and Alcor merge. Cryonics 1981, November(28):1.

19. Staff: Full time Alcor president. Cryonics 1984, August(49):8.

20. Kunen J, Moneysmith, M.: Reruns Will Keep Sitcom Writer Dick Clair on Ice-indefinitely: http://www.people.com/people/archive/article/0,,20120770,00.html. People 1989.

By Mike Darwin

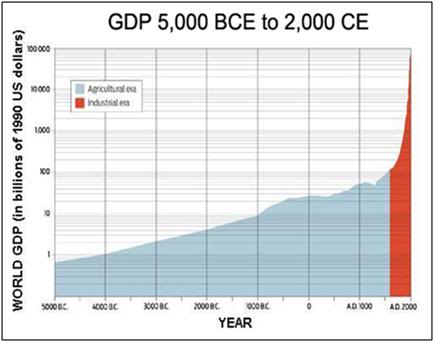

By Mike Darwin Figure 1: The sweep of human wealth production is nicely summarized in this graph of the gross domestic product over the course of the lat 5,000 of civilization. Because of the large time frame and the (necessary) use of a logarithmic scale, global disasters which severely impacted the wellbeing of then extant civilizations are not readily apparent.

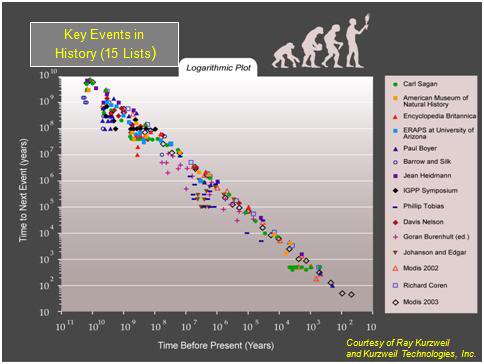

Figure 1: The sweep of human wealth production is nicely summarized in this graph of the gross domestic product over the course of the lat 5,000 of civilization. Because of the large time frame and the (necessary) use of a logarithmic scale, global disasters which severely impacted the wellbeing of then extant civilizations are not readily apparent. Figure 2: This even longer time line of biological and human technological evolution similarly fails to show truly massive setbacks in the course of biological and cultural evolution, such as the Permian extinction, which destroyed ~ 90% of all life on the planet, the Holocene Ice Age, or the century long global drought which began in 2200 BCE.

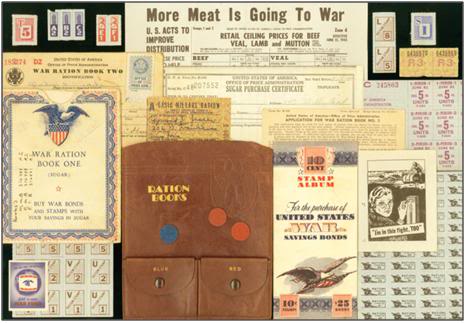

Figure 2: This even longer time line of biological and human technological evolution similarly fails to show truly massive setbacks in the course of biological and cultural evolution, such as the Permian extinction, which destroyed ~ 90% of all life on the planet, the Holocene Ice Age, or the century long global drought which began in 2200 BCE. Figure 3: Virtually every consumer item from meat to fuel was rationed in the US and Canada during World War II. Virtually the entire manufacturing capacity of both nations was focused on war production which included subsistence production for the populations of both nations. http://www.ameshistoricalsociety.org/exhibits/events/rationing.htm

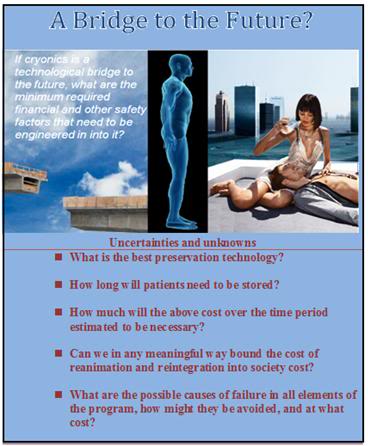

Figure 3: Virtually every consumer item from meat to fuel was rationed in the US and Canada during World War II. Virtually the entire manufacturing capacity of both nations was focused on war production which included subsistence production for the populations of both nations. http://www.ameshistoricalsociety.org/exhibits/events/rationing.htm Figure 4: Fifty years on, cryonicists have yet to rigorously study these questions.

Figure 4: Fifty years on, cryonicists have yet to rigorously study these questions. Figure 5: Optimism about the ability of existing cryonics organizations and their respective facilities to endure the test of time – of the passage of many decades, or even centuries – seems confined almost exclusively to cryonicists. To understand why this should be so it is only necessary to contemplate the cartoon above.

Figure 5: Optimism about the ability of existing cryonics organizations and their respective facilities to endure the test of time – of the passage of many decades, or even centuries – seems confined almost exclusively to cryonicists. To understand why this should be so it is only necessary to contemplate the cartoon above. Figure 6: Timeship: a viable cryonics research and patient storage complex. or an impractical edifice complex?

Figure 6: Timeship: a viable cryonics research and patient storage complex. or an impractical edifice complex? 10 February, 1974 “Air Hearse”

10 February, 1974 “Air Hearse”

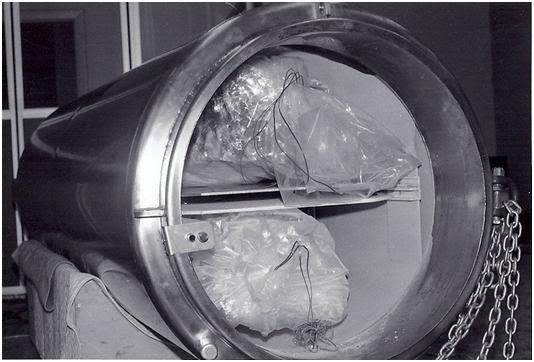

Trans Time’s first two patients, shortly after being placed head down inside a dual patient Minnesota Valley Engineering cryogenic dewar, on 08 February 1974 in Emeryville, California. The dewar was originally constructed to store cryonics patient Clara Dostal, at the facilities of the Cryonics Society of New York on West Babylon, Long Island, NY. However, when Dostal’s son and daughter decided not to proceed with her cryopreservation, the dewar was sold to the son of the patient (RM) whose foil-wrapped feet are visible in the upper part of the unit.

Trans Time’s first two patients, shortly after being placed head down inside a dual patient Minnesota Valley Engineering cryogenic dewar, on 08 February 1974 in Emeryville, California. The dewar was originally constructed to store cryonics patient Clara Dostal, at the facilities of the Cryonics Society of New York on West Babylon, Long Island, NY. However, when Dostal’s son and daughter decided not to proceed with her cryopreservation, the dewar was sold to the son of the patient (RM) whose foil-wrapped feet are visible in the upper part of the unit.

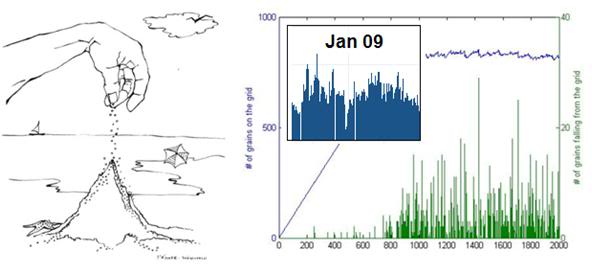

Figure 1: The build up and collapse of sand piles exhibit the property of surface fractals – also called cellular automata. The spikes (green) in the graph at the right of the illustration above show the ups and down of the sand pile’s height over time. The inset (blue) graph shows the Dow Jones Industrial Average during January of 2009. The similarity in the pattern of activity between the DJIA and the behavior of sand piles is almost certainly not a coincidence.

Figure 1: The build up and collapse of sand piles exhibit the property of surface fractals – also called cellular automata. The spikes (green) in the graph at the right of the illustration above show the ups and down of the sand pile’s height over time. The inset (blue) graph shows the Dow Jones Industrial Average during January of 2009. The similarity in the pattern of activity between the DJIA and the behavior of sand piles is almost certainly not a coincidence. Figure 2: Alcor membership from 1972 to 2010. What can be learned from a careful analysis of these data? Is there a discernible reason(s) why growth in membership became nearly exponential, briefly, during the early 1980s?

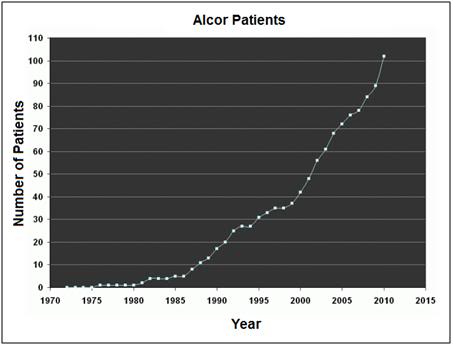

Figure 2: Alcor membership from 1972 to 2010. What can be learned from a careful analysis of these data? Is there a discernible reason(s) why growth in membership became nearly exponential, briefly, during the early 1980s? Figure 3: The Alcor patient population from 1975 to 2010.

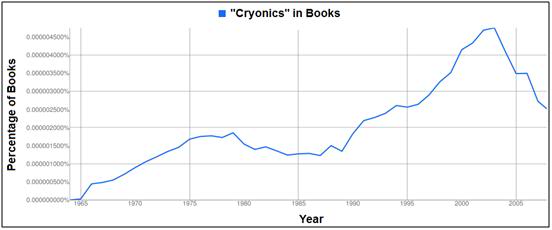

Figure 3: The Alcor patient population from 1975 to 2010.  Figure 4: Google N-gram for the frequency with which the word “cryonics” appears in books published in the English language from 1964 to 2010. Does the shape of this curve reliably correlate with historical events in cryonics?

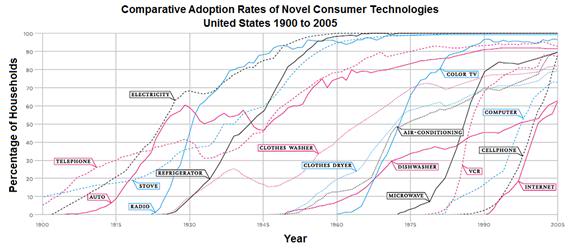

Figure 4: Google N-gram for the frequency with which the word “cryonics” appears in books published in the English language from 1964 to 2010. Does the shape of this curve reliably correlate with historical events in cryonics? Figure 5: The rates at which novel consumer technologies were adopted in the United States.

Figure 5: The rates at which novel consumer technologies were adopted in the United States.  There are also articles from the late 1980s documenting the Dora Kent incident, though the record as represented here is far from complete:

There are also articles from the late 1980s documenting the Dora Kent incident, though the record as represented here is far from complete: Promotional material from the early days of cryonics, such as the full color Cryo-Span brochure have been carefully scanned and restored:

Promotional material from the early days of cryonics, such as the full color Cryo-Span brochure have been carefully scanned and restored:

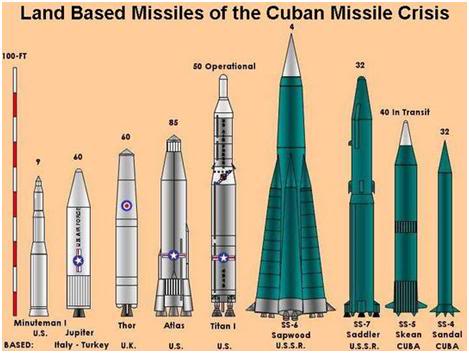

Figure 40: The Soviet “equivalent” of the Titan 1 Missile Site in Pervomaysk, Ukraine. This site was active in 1961 and was one of the first operational ICBM sites.

Figure 40: The Soviet “equivalent” of the Titan 1 Missile Site in Pervomaysk, Ukraine. This site was active in 1961 and was one of the first operational ICBM sites. Figure 41: The comparative bulk and weight of Soviet thermonuclear weapons (as contrasted with those of the US at the time) necessitated the construction of heavy lift boosters with a high specific impulse of thrust. This positioned them perfectly for launching small payloads into stable earth orbit and for launching heavier payloads, such as manned spacecraft, into low earth orbit. All heavy life boosters currently operating are lineal descendants of the SS-6 ICBM.

Figure 41: The comparative bulk and weight of Soviet thermonuclear weapons (as contrasted with those of the US at the time) necessitated the construction of heavy lift boosters with a high specific impulse of thrust. This positioned them perfectly for launching small payloads into stable earth orbit and for launching heavier payloads, such as manned spacecraft, into low earth orbit. All heavy life boosters currently operating are lineal descendants of the SS-6 ICBM.

Figure 46: Launch control room.

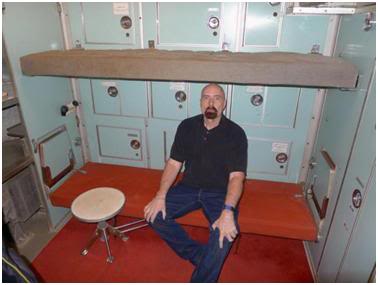

Figure 46: Launch control room. Figure 50: Propellant storage room.

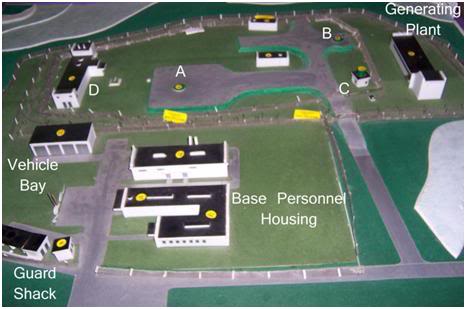

Figure 50: Propellant storage room. Figure 51: Layout of a typical Soviet ICBM site in the 1980s and 1990s. A lower security area of the base fronted the access road and consisted of first tier security facilities, vehicle bays, barracks and infrastructure for base security and support personnel. In back of this area was the high security zone enclosing the missile and associated launch infrastructure. This consisted of housing for the officers and political apparatchiks (D), the underground launch command/control center (A), the R-36 missile silo (B), a hardened security bunker (C) and a surface engineering and power generating plant.

Figure 51: Layout of a typical Soviet ICBM site in the 1980s and 1990s. A lower security area of the base fronted the access road and consisted of first tier security facilities, vehicle bays, barracks and infrastructure for base security and support personnel. In back of this area was the high security zone enclosing the missile and associated launch infrastructure. This consisted of housing for the officers and political apparatchiks (D), the underground launch command/control center (A), the R-36 missile silo (B), a hardened security bunker (C) and a surface engineering and power generating plant. Figure 52: Inner perimeter high tension electric fence. This fence was not present as just as a deterrent; contact with it would have been immediately lethal.

Figure 52: Inner perimeter high tension electric fence. This fence was not present as just as a deterrent; contact with it would have been immediately lethal. Figure 53: The control center was a modular 12-storey facility that was trucked to and from the site for deployment and refurbishment. The control center was shock mounted to withstand a direct nuclear hit with a low mega-tonnage weapon such as the US used at that time. The control center housed the launch control facilities, communications, crew housing and basic life support infrastructure sufficient to permit the survival of 3 men for 45 days.

Figure 53: The control center was a modular 12-storey facility that was trucked to and from the site for deployment and refurbishment. The control center was shock mounted to withstand a direct nuclear hit with a low mega-tonnage weapon such as the US used at that time. The control center housed the launch control facilities, communications, crew housing and basic life support infrastructure sufficient to permit the survival of 3 men for 45 days. Figure 54: At left, one of the specialized vehicles used to raise and lower the command center from its concrete bunker. The circular structure to the right of the vehicle is the top of the command silo, which would be removed to allow the command center to be removed or emplaced.

Figure 54: At left, one of the specialized vehicles used to raise and lower the command center from its concrete bunker. The circular structure to the right of the vehicle is the top of the command silo, which would be removed to allow the command center to be removed or emplaced. Figure 55: Underground access tunnel connecting the above ground facilities and engineering bunker to the command center.

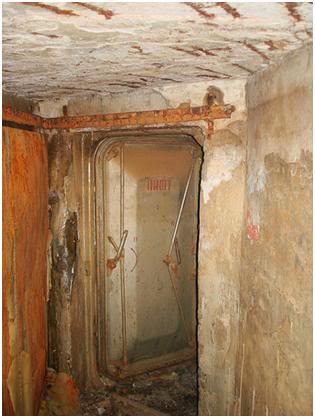

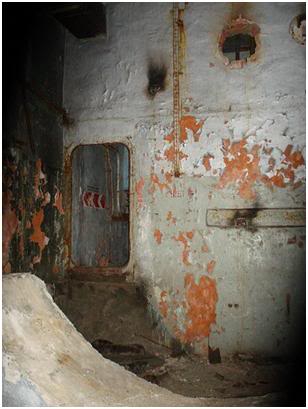

Figure 55: Underground access tunnel connecting the above ground facilities and engineering bunker to the command center. Figure 56: Electrical distribution center in engineering bunker at the R-36 site in Pervomaysk. This bunker was located approximately 4 meters underground adjacent to the missile command center.

Figure 56: Electrical distribution center in engineering bunker at the R-36 site in Pervomaysk. This bunker was located approximately 4 meters underground adjacent to the missile command center. Figure 57: Some of the air handling equipment supporting the control center located in the engineering bunker.

Figure 57: Some of the air handling equipment supporting the control center located in the engineering bunker.  Figure 58: At left, primary personnel entry blast door which protects the control center silo contents. At right, just beyond the blast door is a 3-3 man elevator that provided routine acess to the control center.

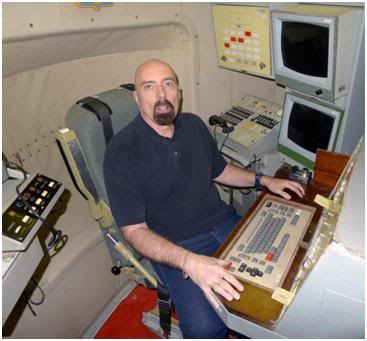

Figure 58: At left, primary personnel entry blast door which protects the control center silo contents. At right, just beyond the blast door is a 3-3 man elevator that provided routine acess to the control center. Figure 59: The author, sitting in the commander’s chair at the R-36 launch control panel. The Soviet’s used a two key system that operated on the same principle as that employed in US ICBM installations. Each officer had a key and both keys and accompaning codes were required to be used before launch could take place. The officers staffing the control center were stationed at two launch control consoles sufficiently far apart that both men would have to be present and functioning in order to initiate a launch. Unless, of course, there was an override from the Kremlin.

Figure 59: The author, sitting in the commander’s chair at the R-36 launch control panel. The Soviet’s used a two key system that operated on the same principle as that employed in US ICBM installations. Each officer had a key and both keys and accompaning codes were required to be used before launch could take place. The officers staffing the control center were stationed at two launch control consoles sufficiently far apart that both men would have to be present and functioning in order to initiate a launch. Unless, of course, there was an override from the Kremlin.

Figure 65: One of the remote launch antennae pointed towards Moscow.

Figure 65: One of the remote launch antennae pointed towards Moscow. Figure 65: Top: Blast hardened cover to the R-36 silo. Bottom: A peek inside an R-36 missile silo. Decomissioned silos were filled with concrete and there is standing rainwater barely visible towards the bottom center of the photo above. The uptilting metal plates present in two tiers adjacent to the ladder were work platforms to allow technicians to service themissile in situ.

Figure 65: Top: Blast hardened cover to the R-36 silo. Bottom: A peek inside an R-36 missile silo. Decomissioned silos were filled with concrete and there is standing rainwater barely visible towards the bottom center of the photo above. The uptilting metal plates present in two tiers adjacent to the ladder were work platforms to allow technicians to service themissile in situ.

The story below, claiming that Britney Spears is interested in making cryopreservation arrangements with the Alcor Life Extension Foundation, appeared in the British tabloid The Sun on 25 May, 2011. The Sun is one of Rupert Murdoch’s many (Fox News) sad efforts at journalism. And whilst it is a tabloid, it is enormous in its size and reach. This means that objective claims it makes about celebrities must be taken more seriously than, say, those of the National Enquirer, in the US. This is so because The Sun is published in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland (where it is known as The Irish Sun) where libel and invasion of privacy laws are quite strict and the penalties for defamation, or even for just invading personal privacy, can be severe. With an average daily circulation of ~ 2,904,180, The Sun has a lot to lose if it too cavalierly publishes detailed lies – even if they are about a celebrity as notoriously volatile and controversial as the pop singing star Britney Spears. The Sun is by far the largest newspaper in the UK (having long ago eclipsed The Times and The Guardian ) with an estimated daily readership of ~ 7,700,000; and it is the 10th largest newspaper in the world.

The story below, claiming that Britney Spears is interested in making cryopreservation arrangements with the Alcor Life Extension Foundation, appeared in the British tabloid The Sun on 25 May, 2011. The Sun is one of Rupert Murdoch’s many (Fox News) sad efforts at journalism. And whilst it is a tabloid, it is enormous in its size and reach. This means that objective claims it makes about celebrities must be taken more seriously than, say, those of the National Enquirer, in the US. This is so because The Sun is published in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland (where it is known as The Irish Sun) where libel and invasion of privacy laws are quite strict and the penalties for defamation, or even for just invading personal privacy, can be severe. With an average daily circulation of ~ 2,904,180, The Sun has a lot to lose if it too cavalierly publishes detailed lies – even if they are about a celebrity as notoriously volatile and controversial as the pop singing star Britney Spears. The Sun is by far the largest newspaper in the UK (having long ago eclipsed The Times and The Guardian ) with an estimated daily readership of ~ 7,700,000; and it is the 10th largest newspaper in the world.