By Mike Darwin

Introduction: The Magical Biomarker

As I was leaving the conference exhibitors area, I was waylaid by Dr. Veerappan Chithambaram, the conference organizer. “Mike, there is someone I think you should talk to. I don’t know exactly why, but I think it is important for the two of you to meet.” “What is our area of mutual interest?” I asked. “Well, you must come and meet Henrik, and then you will know.”

After the presentations were over for the day, Henrik Tommerup and I sat in the bar of the hotel and talked. The bar was deserted. Prince William and Kate Middleton were getting married and it was the day of the traditional “wedding parties,” where citizens of the Empire throw their own celebrations, often in the form of street parties a day or two before the royal wedding itself. Henrik Tommerup is Vice President of Business Development for the Danish biotechnology company, ViroGates. He is an intelligent and highly articulate man whose most outstanding characteristic is his earnest and controlled enthusiasm. As we talk, I rather imagine that this must have been what it must have been like to talk with one of that wave of young merchants who created the East India Company. As the conversation proceeds and heats up, Henrik hands me journal article after journal article. As I begin to absorb the graphic data – it occurs to me why I am thinking of him in such terms. What he is telling me is potentially of great importance. In fact, if it is real, it will be of comparable importance to the discovery of the link between hypertension and death and disease from heart attack, stroke and kidney failure.

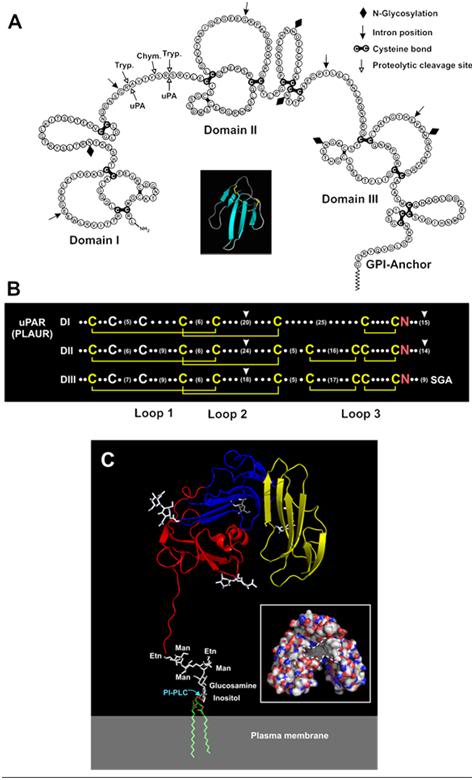

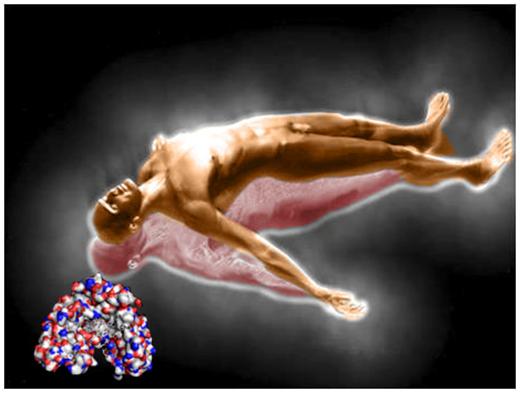

Figure 1: Soluble urokinase plasma receptor (suPAR). Panel A – Schematic representation of the amino acid sequence of human uPAR showing its three homologous LU domains. Consensus disulfide bonds defining the LU domains are coloured black. The position of the C-terminal glycolipid anchor (GPI) is shown (modified from Ploug and Ellis, 1994, with permission). Insert: The archetypical three-finger fold is illustrated by a ribbon diagram for a single secreted LU-domain protein (snake venom toxin-a) using the PDB coordinates 1NEA and PyMOLTM (DeLano Scientific). Panel B – LU domain signatures in the primary sequence of human uPAR. The three LU domains (DI, DII and DIII) of uPAR are aligned with the consensus structures being highlighted (disulfide bonds in yellow and the invariant asparagines in red). The number of residues between the individual cysteines is represented by dots or numbers in brackets (modified from Kjaergaard et al., 2008). Panel C – The crystal structure solved for uPAR in complex with a peptide antagonist is shown as a ribbon diagram (Llinas et al., 2005). The individual LU domains are colour-coded (DI in yellow, DII in blue and DIII in red), and N-linked carbohydrates are shown as white sticks. The attachment to the cell surface by a glycolipid anchor is modelled in this cartoon. The insert shows uPAR in a surface representation, with the hydrophobic ligand-binding cavity marked with hatched lines; carbon, nitrogen and oxygen atoms are coloured white, blue and red, respectively. These structures are visualized by PyMOLTM (DeLano Scientific), using the PDB coordinates 1YWH (reproduced from Kjaergaard et al., 2008).[1]

Figure 1: Soluble urokinase plasma receptor (suPAR). Panel A – Schematic representation of the amino acid sequence of human uPAR showing its three homologous LU domains. Consensus disulfide bonds defining the LU domains are coloured black. The position of the C-terminal glycolipid anchor (GPI) is shown (modified from Ploug and Ellis, 1994, with permission). Insert: The archetypical three-finger fold is illustrated by a ribbon diagram for a single secreted LU-domain protein (snake venom toxin-a) using the PDB coordinates 1NEA and PyMOLTM (DeLano Scientific). Panel B – LU domain signatures in the primary sequence of human uPAR. The three LU domains (DI, DII and DIII) of uPAR are aligned with the consensus structures being highlighted (disulfide bonds in yellow and the invariant asparagines in red). The number of residues between the individual cysteines is represented by dots or numbers in brackets (modified from Kjaergaard et al., 2008). Panel C – The crystal structure solved for uPAR in complex with a peptide antagonist is shown as a ribbon diagram (Llinas et al., 2005). The individual LU domains are colour-coded (DI in yellow, DII in blue and DIII in red), and N-linked carbohydrates are shown as white sticks. The attachment to the cell surface by a glycolipid anchor is modelled in this cartoon. The insert shows uPAR in a surface representation, with the hydrophobic ligand-binding cavity marked with hatched lines; carbon, nitrogen and oxygen atoms are coloured white, blue and red, respectively. These structures are visualized by PyMOLTM (DeLano Scientific), using the PDB coordinates 1YWH (reproduced from Kjaergaard et al., 2008).[1]

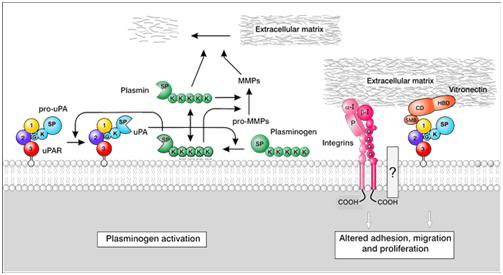

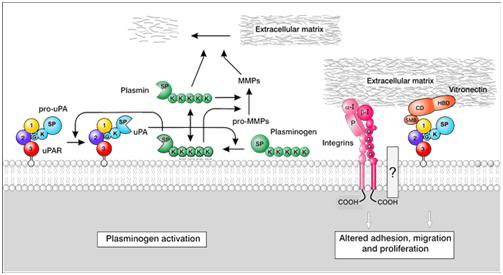

Soluble urokinase receptor, or suPAR, for short, is the soluble form of the urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR), which is expressed in a fairly broad range of immune cells. uPAR is a fascinating molecule. It is part of the tissue plasminogen activation system which is critically involved in tissue remodeling and reorganization, such as occurs in wound healing, tumor growth and mammary gland involution.[1] In order for tissue remodeling to proceed it is first necessary to degrade and destroy the existing cellular and extracellular structures. This is accomplished in part by activation of the plasminogen activation cascade. uPAR acts to confine plasminogen activation to the vicinity of the cell membranes involved in remodeling by binding to urokinase and inhibiting its proteolytic activity. Studies suggest that suPAR is a regulator of uPAR/uPA actions through competitive inhibition of uPAR; and several studies conclude that the cleaved receptor is a chemotatic agent promoting the immune response.

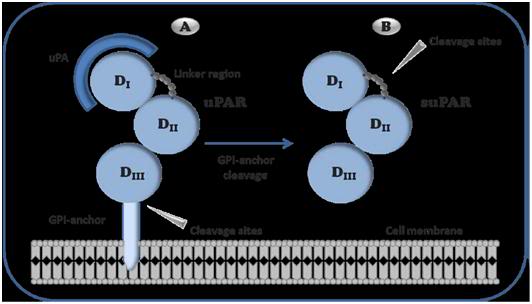

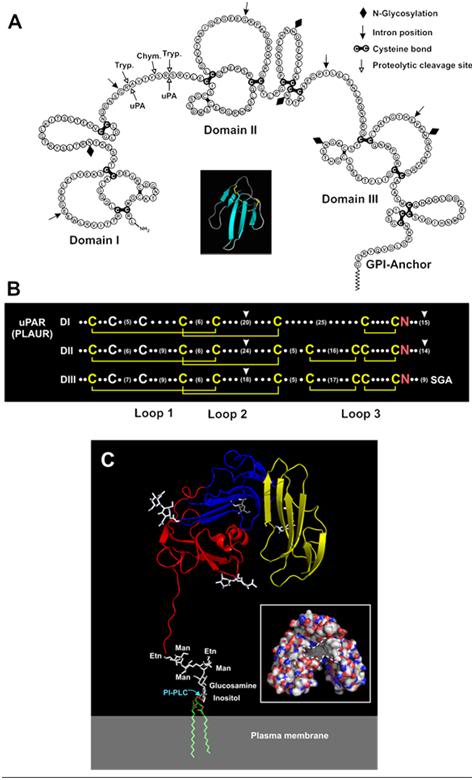

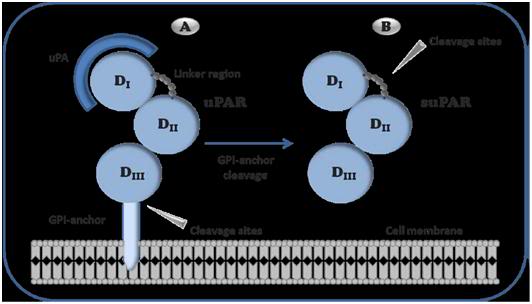

Figure 2: Schematic representation of urokinase receptor The GPI-anchor links uPAR to the cell membrane making it available for uPA to bind to the receptor. When the receptor is cleaved between the GPI-anchor and D3, it becomes soluble (suPAR). suPAR is a stable protein that can be measured in various body fluids. uPA: urokinase-type plasminogen activator, uPAR: uPA receptor, suPAR: soluble uPAR, 1: Domain 1, D2: Domain 2, D3: Domain 3.

Figure 2: Schematic representation of urokinase receptor The GPI-anchor links uPAR to the cell membrane making it available for uPA to bind to the receptor. When the receptor is cleaved between the GPI-anchor and D3, it becomes soluble (suPAR). suPAR is a stable protein that can be measured in various body fluids. uPA: urokinase-type plasminogen activator, uPAR: uPA receptor, suPAR: soluble uPAR, 1: Domain 1, D2: Domain 2, D3: Domain 3.

Under conditions of inflammation – any inflammation – uPAR is cleaved from the cell surfaces by proteases and converted to the soluble form of the receptor (suPAR), which subsequently becomes distributed in blood, urine and cerebrospinal fluid.[2-5] Immune activation caused by infectious disease, atherosclerosis, autoimmune disease and a wide variety of solid tumors results in the cleavage of uPAR from cell membranes and thus creates an easily detectable signal in the form of increased levels of suPAR in body fluids. As a consequence, serum suPAR levels are believed to mirror the degree of immunoactivation in an individual.

It appears that suPAR may be the Holy Grail of inflammation, since it is exquisitely sensitive at detecting immune-mediated inflammation in HIV, malaria, tuberculosis, and in healthy subjects subjected to pro-inflammatory stressors, such as cigarette smoking, lack of exercise and poor diet.[6, 7] suPAR level is positively correlated with markers of inflammation and immune activation such as CRP (hsCRP), TNF-a, s-TREM-1, MIF, GM-CSF, the pro-inflammatory ILs and total white blood cell count.[2] Thus, suPAR may be a novel marker of inflammation, and increased inflammation has in recent years been suggested as the primary driving mechanism in age-associated degenerative diseases. Nevertheless, suPAR remains associated with disease endpoints after the adjustment of other inflammatory markers and is less related to metabolic variables than CRP. Thus suPAR may reflect another aspect of inflammation than do the classical markers.

Figure 3: uPAR ligands. Schematic representation of the functions of uPAR via its interaction with uPA, integrins, and vitronectin (modified from Kjaergaard et al., 2008)[1].

Figure 3: uPAR ligands. Schematic representation of the functions of uPAR via its interaction with uPA, integrins, and vitronectin (modified from Kjaergaard et al., 2008)[1].

Since there are no genetic polymorphisms in humans which cause suPAR to be expressed in the absence of inflammation, elevated suPAR levels are always a marker for the presence of active inflammation. suPAR levels are also rapidly and uniformly responsive to positive treatment intervention. In acute infections disease such as sepsis, suPAR levels begin to decline in response to effective treatment within a few hours. Getting the treatment “right” quickly for septic patients is critical, because every hour spent in a state of hyper-immune driven organ injury translates to a big increase in mortality, as well as in costly time spent in the ICU

What are Your Risks?

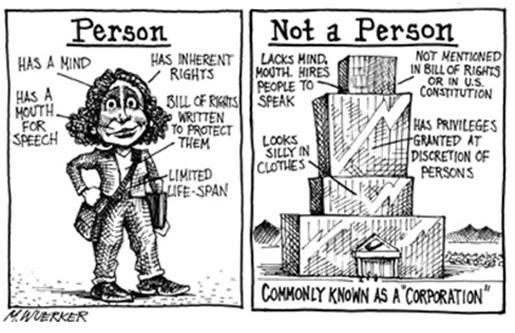

What ViroGates (or more accurately one of its co-founders, Jesper Eugen-Olsen[4, 6]) has discovered, it seems, is a cheap, simple and inexpensive test that will tell a person what his chances are of dying from anything other than accident, homicide, and (maybe) suicide. No, they aren’t claiming that, and the current market for their product is mostly Africa. They are Dutch and the Dutch are, if anything, all about understatement. Nevetheless, Henrik knows that I know exactly what the score is. And what’s more, we both now understood why Veerappan had brought us together. This is going to be big, really big, and my mind boggled as I sat there looking at the data.

The test ViroGates has developed is called suPARnostic® and it is an rapid, enzyme-linked serum assay (ELISA) for the suPAR protein. ELISA technology has undergone rapid perfection over the past decade and now allows for effective diagnosis of everything from HIV to urinary tract infections. ELISA technology has revolutionized the detection of sexually transmitted diseases; it is no longer necessary to painfully invade the urethra with a wire loop to obtain a culture swab for gonorrhea – a few drops of urine suffice and the test can be done in the privacy of your own home. Similarly, Chlamydia, which is almost impossible to culture, and which is the organism primarily responsible for pelvic inflammatory disease in women and what was formerly called non-specific urethritis (NSU) in men, can be detected with a few drops urine. As I sit listening to Henrik and taking in the data, the first thought that comes into my mind is the life insurance industry.

ViroGates’ test is so sensitive and specific it could revolutionize life insurance. Not since the first actuaries began their toils for the Society for Equitable Assurances on Lives and Survivorships in London, in 1762, has anything so potentially profitable come along for the life (and health) insurance industry. In his 1939 story “Life-Line,” science fiction writer Robert Heinlein (1907-1988) posited the invention of a device that would predict, with accuracy, when a person would die. In his story, the device devastates the life insurance industry, because potential customers could stack the deck against the insurers. Why Heinlein didn’t see the more obvious outcome, namely that the insurance companies would stack the deck against their customers, I have no idea. However, Henrik is not enthused about the life insurance application. After all, it is painfully obvious, it would be illegal in Europe, he informs me, and I can see the idea offends his Dutch sense of fair play.

As I look at paper after paper the truly global import of this single biomarker begins to come into focus. The MONICA10 study was a population-based cohort recruited from Copenhagen, Denmark, that included 2,602 individuals aged 41, 51, 61 or 71 years.[8] Its purpose was to determine if suPAR levels predicted mortality in representative cohorts of the population in urban Denmark: i.e., an ethnically and comparatively genetically homogenous Caucasian population. Blood samples were collected from the study participants over a 12.5 year period and were analyzed for suPAR levels using the suPARnostic® enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Other biomarkers of inflammation, such as C-reactive protein, were also evaluated. The study results demonstrated that risk of cancer CVD and overall mortality (assessed with a multivariate proportional hazards model using Cox regression) was strongly correlated with suPAR levels. This correlation was more prognostic in men than in women, and in younger as compared with older individuals.[7]

Figure 4: The optimum level of circulating suPAR appears to be below 2.0 ng/mL in men and 2.5 ng/mL or lower in women. In the healthy population, risk of disease or death rises sharply as the suPAR level increases. The circulating suPAR level increases sensitively with lifestyle choices know to be associated with increased risk of illness and death, such as tobacco abuse, obesity and a sedentary lifestyle – but not to the same degree in all individuals. In fact, suPARnostic® testing may allow clinicians (and theoretically tobacco companies and smokers) to determine those patients for whom smoking, obesity or other “harmful” lifestyle choices pose much less risk.

Figure 4: The optimum level of circulating suPAR appears to be below 2.0 ng/mL in men and 2.5 ng/mL or lower in women. In the healthy population, risk of disease or death rises sharply as the suPAR level increases. The circulating suPAR level increases sensitively with lifestyle choices know to be associated with increased risk of illness and death, such as tobacco abuse, obesity and a sedentary lifestyle – but not to the same degree in all individuals. In fact, suPARnostic® testing may allow clinicians (and theoretically tobacco companies and smokers) to determine those patients for whom smoking, obesity or other “harmful” lifestyle choices pose much less risk.

The presence of an elevated baseline suPAR level was associated with an increased risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes and overall mortality during the course of the study. An elevated serum suPAR level was most strongly associated with cancer, CVD and with mortality in men as opposed to women, and in younger compared with older individuals. Elevated suPAR remained significantly associated with the risk of negative outcome even after adjustment for a number of relevant risk factors, including C-reactive protein levels. The ability of the suPARnostic® test to predict mortality and morbidity in the study population was ~ 85%![9] In other words, 85% of the population who experienced death or serious illness from degenerative disease (cancer, CVD, etc.) had markedly elevated suPAR levels.

This is perhaps not surprising when consideration is given to the fact that the common pathophysiological mechanism/finding in virtually all degenerative diseases is inflammation. An important caveat is that this study will have to be extended and expanded to verify its validity in ethically more diverse populations. Because of where it was carried out, the MONICA10 study was confined almost exclusively to Caucasians. Other tests for biomarkers of inflammation such as C -reactive protein, Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF), and various pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1[1], IL-6, IL-8, GM-CSF, TNF-alpha, sTREM-1, and MIF) show too much fluctuation and individual variability to be of similarly potent prognostic use.[7, 8, 10-12] This may be because these molecules are elaborated much further downstream in the inflammation process than is suPAR and they may be elaborated in response to intercurrent processes that take place over the long course of a morbid, pro-inflammatory illness. Conversely, suPAR levels decline with remarkable speed once the inflammation process is halted or moderated by effective treatment.

suPARnostic® in the Critically Ill

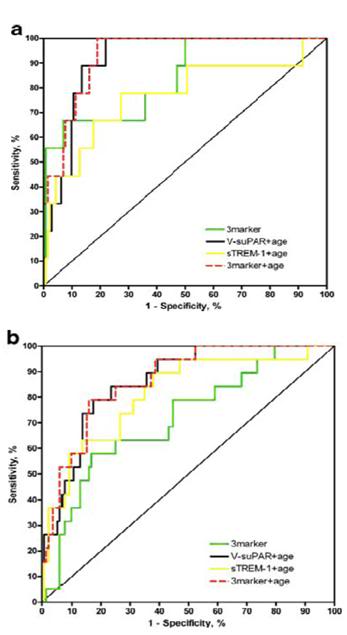

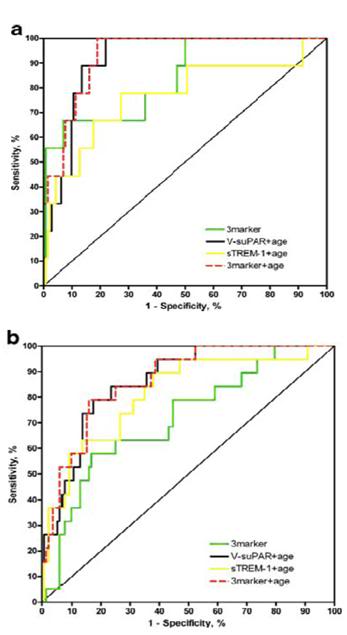

The use of suPAR measurement seems likely to be of great value as triage tool for patients admitted to the Emergency Department (ED). Elderly patients with sepsis or who are in the early stages of the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS), often present with minimal symptoms. Even when septic they may not have markedly elevated temperatures and their white blood cell count may not be alarmingly high; old age is, after all, a potent immunosuppressant. It is frequently difficult to rapidly determine just how sick these individuals are. The use of suPARnostic® could prove lifesaving such a situation. Even patients who are clearly seriously ill are difficult to categorize or prognosticate. Which patients need immediate and aggressive treatment in the Intensive Care Unit? suPARnostic® measurements of 6.0 ng/mL to double digit levels are indicative of serious illness that is progressing rapidly and is potentially life threatening and patients with suPARnostic® levels above 15 ng/m have been found to be uniformly gravely ill, with many of them dying shortly after presentation and suPAR level measurement. The power of an objective clinical measurement to categorize patients by prognostication with such a high degree of accuracy should prove invaluable, both in saving lives and in containing health care costs. The ability of suPARnostic® testing as compared to the commonly used multiplex immunoassay for pro-inflammatory cytokines to predict 30-day mortality and 180-day mortality in a prospective study of a group of patients presenting to hospital with SIRS in shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve comparing composite marker’s ability to predict mortality. ROC curves comparing suPAR measured with suPARnostic® (V-suPAR) combined with age (AUC=0.92), soluble triggering receptor expressed on myoloid cells-1 (sTREM-1) combined with age, V-suPAR, sTREM-1 and macrophage migration inhibitory factor ROC curves combined as the 3-marker, and the 3-marker combined with age. Prediction of 30-day mortality (a) and 180-day mortality (b) prospectively collected cohort of patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) that were admitted to an emergency department and a department of infectious diseases at a university hospital.[12]

Figure 5: Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve comparing composite marker’s ability to predict mortality. ROC curves comparing suPAR measured with suPARnostic® (V-suPAR) combined with age (AUC=0.92), soluble triggering receptor expressed on myoloid cells-1 (sTREM-1) combined with age, V-suPAR, sTREM-1 and macrophage migration inhibitory factor ROC curves combined as the 3-marker, and the 3-marker combined with age. Prediction of 30-day mortality (a) and 180-day mortality (b) prospectively collected cohort of patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) that were admitted to an emergency department and a department of infectious diseases at a university hospital.[12]

A Focus on the Third World

When suPARnostic® testing was combined with the patients age, or with the patients age and 3 pro-inflammatory biomarkers known to be ass0ciated with increased mortality, suPARnostic® testing was highly predictive of outcome. Cytokine testing, the current competitor to the uPARnostic® test is costly and difficult to do and for these reasons is not routinely used in hospital. Outcomes in patients with TB, meningitis, and HIV are also well prognosticated by suPAR levels during treatment. In fact, the major focus of ViroGates is not on the degenerative diseases of the Developed World, but rather on the diseases of Africa and the Third world; primarily malaria[13], TB[14-17] and HIV. suParnostic® testing has proved highly predictive of both response to treatment and to outcome. It will also very likely be of use in determining which patients with HIV need highly active anti-retroviral treatment (HAART) and which patients can delay treatment, since suPAR levels are closely correlated with the progression of the disease from infection to serious immunosuppresion and death.[16, 18-20] Being able to select only those patients in need of treatment offers the potential benefit of greatly reducing costs, reducing viral resistance, and reducing the morbidity due to the toxicity of HAART.[16, 19]

The Tobacco (and Junk Food) Companies’ Wet Dream?

It is the job of epidemiologist to find correlations between morbidity and mortality and factors in the environment. Prior to the 20th century, this concern was focused almost exclusively on infectious disease. Whilst people died from cardiovascular disease and cancer, most simply didn’t live long enough to develop these diseases of aging. As life spans grew longer due to public health measures and reduced infant mortality, the focus of epidemiology shifted to non-communicable environmental risk factors. Cardiovascular disease and cancer quickly became the leading causes of illness and death and it slowly became apparent that the biggest risk factors associated with those diseases (other than aging itself) were carcinogens in the environment, excessive calorie consumption (obesity) and a sedentary lifestyle – with alcohol abuse coming in closer to the bottom than the top (a fact that would have shocked and surprised the temperance advocates of the 19th and 20th centuries). Of all the environmental carcinogens, none proved as powerful a contributor to disease and death as tobacco use, and cigarette smoking, in particular.

However, it is important to understand that epidemiologists deal with humans mostly in herds. Their pronouncements in the arena of environmental hazards are necessarily statistical and that is something that physicians and moralists all too often forget. We are told that smoking causes cancer – and indeed it does – but in whom? On the question of precisely which individuals in the population are or are not risk, epidemiology is necessarily silent. However, if you are much older than 30 and you pay attention to the people being picked off by death around you, you can’t help but notice that some people seem to get to break the rules.

My own father is a case in point. He began smoking when he was 13 years old – his preference was Camels – 3 packs a day – fortunately, unfiltered.[3] He is 90 today – alive and living independently. In addition to smoking, he consumed alcohol well beyond the medically countenanced “healthy limits” for much of his life. He did require replacement of his abdominal aorta 6 years ago – at which point he finally quit smoking. Aside from the intra-abdominal aortic aneurysm, peripheral artery disease of long standing, and some coronary insufficiency nearly 20 years ago (angioplasty) he has not developed either of the other two big smoking related illnesses; cancer and emphysema. Similarly, history abounds with people like Winston Churchill, who smoked and drank with abandon, and yet still lived into old age. Why?

The answer is that these individuals have something fundamentally different about the way they handle environmental insults and very likely how they moderate their immune-inflammatory response. They may also have better DNA repair. The point is, it would be incredibly valuable for tobacco companies, and the purveyor of junk food and alcohol, to determine who can safely use their products, and who will be killed by them. It would be even more useful if their customers could titrate the “dose” of these products to an acceptable level of risk. Maybe you can’t smoke 3-packs of cigarettes a day, but a 1-pack a day habit may carry very little risk – for you. While suPAR alone is not likely to prove a magic bullet in this respect, it seems very likely, bordering on certain, that evaluation of a combination of biomarkers may allow individuals (or corporations) to quantify their risks with a high degree of precision.

Cryonics and Life Extension

As Henrik and I talked on past the setting sun in Manchester, I had only two “novel” suggestions to make regarding potential immediate markets for suPARnostic®: the life extension and cryonics communities. The latter is clearly not going to be a significant market, but the former may well be worth ViroGates pursuing. Currently, biomarkers for disease are disease specific. An elevated CRP is certainly suggestive of increased risk of CVD, and so are elevated HDLs , low LDLs and a high total cholesterol. However none of these tests is very specific and if you want to know what your risk for falling over from a heart attack or stroke is, then you must do multiples of these tests, and preferably others as well, such as homocysteine levels, blood pressure, redox status, and so on.

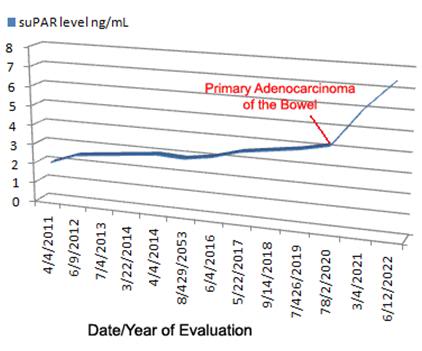

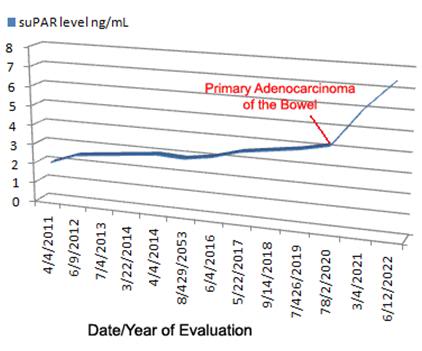

Figure 6: Monitoring of suPAR levels over time is likely to produce data such as is hypothesized above. Adverse and persistent poor lifestyle choices lead to a gradual elevation of suPAR until a lethal event occurs; in this case metastatic colon cancer. suPAR monitoring may allow for early detection of “acute” morbid processes such as cancer.

Figure 6: Monitoring of suPAR levels over time is likely to produce data such as is hypothesized above. Adverse and persistent poor lifestyle choices lead to a gradual elevation of suPAR until a lethal event occurs; in this case metastatic colon cancer. suPAR monitoring may allow for early detection of “acute” morbid processes such as cancer.

This is costly and time consuming and mostly it tells you just one thing – what your risk is for CVD. It says nothing about cancer, nothing about diabetes, and nothing about your overall likelihood of dying. Other tests are required to determine individual disease-specific risks. suPARnostic® testing offers the very real prospect of changing all that. If your suPAR level is elevated and remains so, then it is a foregone conclusion that you have a serious pro-inflammatory process underway. And what that means is that probably sooner, rather than later, you are going to get sick – very sick.

While it may seems strange to discuss exercise under the heading of tobacco and junk food, suPARnostic® testing may help to resolve another heretofore nettlesome and contentious issue, namely is there such a thing as too much exercise? The studies haven’t been done yet but it is clear that too little exercise raises suPAR levels and that people who engage in chronic high impact exercise also have elevated levels. So the question is, can suPARnostic® testing provide a way for the individual to determine out how much exercise is “just right” for him?

Preventative Prognostication

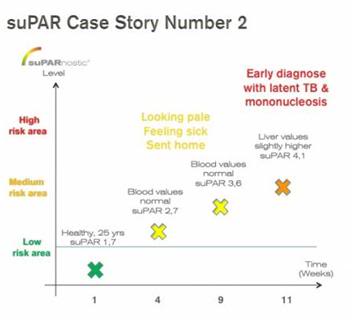

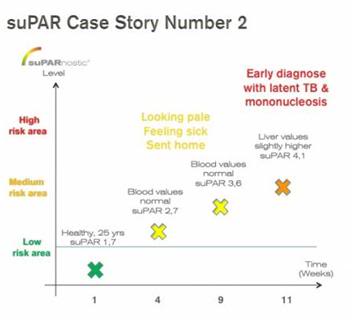

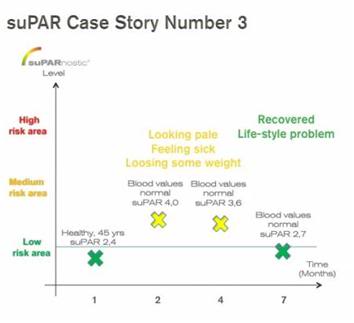

suPARnostic® testing will also tell you what your risk of dying is with greater and greater precision the longer your suPAR level remains elevated. It is also very likely that by looking at the plot of an individual’s plasma suPAR over time it may be possible to observe the risk of mortality reach a critical threshold (Figure 6). Because suPAR levels increase sharply with the onset of cancer and some infectious diseases, it may be possible to detect illness early and intervene. The suPARnostic® website http://suparnostic.com/ provides a couple case examples which are probably representative of what the test can do in the Developed World:

CASE 2: Healthy male, age 25 years, experienced a continuing “feeling sick” and symptoms like being pale, being tired. Repeated doctors visits resulted in no diagnosis, all blood values were normal, no further tests were authorized.

CASE 2: Healthy male, age 25 years, experienced a continuing “feeling sick” and symptoms like being pale, being tired. Repeated doctors visits resulted in no diagnosis, all blood values were normal, no further tests were authorized.

The slowly rising suPAR value predicted that the person was developing a potential critical condition, and at suPAR value 4,1 the person was admitted to an Emergency Room at request of ViroGates.

A series of more elaborate tests diagnosed the person with latent tuberculosis and mononucleosis. As a result of the early recognition, the person did not require a single hospital day, no drug treatment and had to take almost no sick days. More sleep, no sport, no alcohol were sufficient for healing.

Too late recognition would have involved sick days, medical treatment and eventually even hospitalization days. suPARnostic® was an early and correct warning sign.

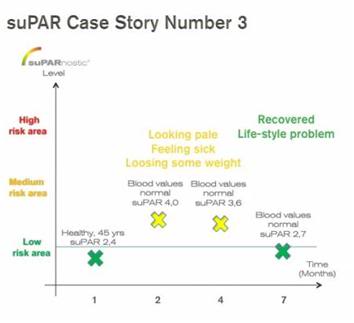

CASE 3: Healthy male, age 45, experienced the same symptoms as Case 2 above, including loss of some weight. Blood values were normal and the person’s suPAR level was slightly elevated, but was not rising into the critical area

CASE 3: Healthy male, age 45, experienced the same symptoms as Case 2 above, including loss of some weight. Blood values were normal and the person’s suPAR level was slightly elevated, but was not rising into the critical area

Adjustment of lifestyle (more sleep, better food, more sport) lowered the suPAR level a few months later into the “normal” area. suPARnostic® recognized correctly that this person was not a critical case requiring immediate hospital attention.

Summary

Figure 8: The ELISA-based suPARnostic® test system is available not only in a high throughput configuration, but also as individual tests that can be performed on-site and in real time, in the same way that the “instant” ELISA-based at-home tests for HIV, Hepatitis C, gonorrhea, Chlamydia, syphilis now do: http://www.curaherbdistributor.com/

In Heinlein’s story about the death prognosticating machine, a great deal of the pathos that attended the invention was that there was nothing that could be done to influence the outcome. The machine told you when you were going to die with certainty. The only planning open to you was to set your affairs in order. Clearly, suPARnostic® testing will have this characteristic in many cases, but it also offers the possibility of intervention to alter the outcome. By changing lifestyle and seeking medical attention earlier it should be possible to reduce disease and delay mortality. For a few of us, it may even offer the prospect of having our cake and eating it too.

Since suPAR levels rise only modestly in “normal healthy” aging it will not likely be a useful biomarker for evaluating interventive gerontology strategies. It should, however, alert us to the importance of doing (and remaining compliant in doing) those things we already know will extend healthy and productive lifespan, such as taking adequate exercise, following an anti-inflammatory diet such as the Mediterranean diet, and avoiding drug, tobacco and alcohol abuse.

In the setting of cryonics, when patients are diagnosed with a serious and potentially fatal illness, such as cancer or cardiovascular disease, suPARnostic® testing should be useful in allowing both the patient and the cryonics organization to better understand the patient’s response to treatment, when failure of treatment has occurred, and finally to better bound the time course to the agonal phase of the illness.

I’ve not been in touch with Henrik since the conference in Manchester. I doubt very much that any of the suggestions I made were of much use to him, or ViroGates. That being said, I’m very glad that I took the opportunity Veerappan provided me with to talk to him. suPARnostic testing is by no means a diagnostic panacea, but I think it will very likely be a game changer in both public health and in critical care medicine. I’m grateful to have had a sneak peek at the goods before they roll out to fully take their place in history.

References

1. Kjaergaard M, Hansen LV, Jacobsen B, Gardsvoll H, Ploug M: Structure and ligand interactions of the urokinase receptor (uPAR). Front Biosci 2008, 13:5441-5461.

2. Stephens R, Pedersen, AN, Nielsen, HJ, Hamers, MJ, Hoyer-Hansen, G, Ronne, E, Dybkjaer, E, Dano, K, Brunner, N. : ELISA determination of soluble urokinase receptor in blood from healthy donors and cancer patients. Clin Chem 1997, 43::1868-1876.

3. Sier C, Sidenius, N, Mariani, A, Aletti, G, Agape, V, Ferrar,i A, Casetta, G, Stephens, RW, Brunner, N, Blasi, F.: Presence of urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor in urine of cancer patients and its possible clinical relevance. Lab Invest 1999, 79:717-722.

4. Ostergaard C, Benfield, T, Lundgren, JD, Eugen-Olsen, J.: Soluble urokinase receptor is elevated in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with purulent meningitis and is associated with fatal outcome. Scand J Infect Dis 2004, 36:14-19.

5. De Witte H, Sweep, F, Brunner, N, Heuvel, J, Beex, L, Grebenschikov, N, Benraad, T.: Complexes between urokinase-type plasminogen activator and its receptor in blood as determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Int J Cancer 1998, 77:236-242.

6. Eugen-Olsen J, Gustafson, P, Sidenius, N, Fischer, TK, Parner, J, Aaby, P, Gomes, VF, Lisse I. : The serum level of soluble urokinase receptor is elevated in tuberculosis patients and predicts mortality during treatment: a community study from Guinea-Bissau. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2002,, 6:686-692. 7. Cobos E, Jumper C, Lox C: Pretreatment determination of the serum urokinase plasminogen activator and its soluble receptor in advanced small-cell lung cancer or non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2003, 9(3):241-246.

8. Eugen-Olsen J, Andersen, O, Linneberg, A, Ladelund, S, Hansen, TW, Langkilde, A, Petersen, J, Pielak, T, Møller, LN, Jeppesen, J, Lyngbaek, S, Fenger, M, Olsen, MH, Hildebrandt, PR, Borch-Johnsen, K, Jørgensen, T, Haugaard SB.: Circulating soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor predicts cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and mortality in the general population. J Intern Med 2010 268(3):296-308.

9. Thunø M, Macho, B, Eugen-Olsen, J.: suPAR: the molecular crystal ball. Dis Markers 2009, 27(3):157-172.

10. Boedhi-Darmojo R, Setianto B, Sutedjo, Kusmana D, Andradi, Supari F, Salan R: A study of baseline risk factors for coronary heart disease: results of population screening in a developing country. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique 1990, 38(5-6):487-491.

11. Supariwala A, Uretsky S, Singh P, Memon S, Khokhar SS, Wever-Pinzon O, Atluri P, Hersh J, Koppuravuri HK, Rozanski A: Synergistic effect of coronary artery disease risk factors on long-term survival in patients with normal exercise SPECT studies. J Nucl Cardiol, 18(2):207-214; quiz 217.

12. Kofoed K, Eugen-Olsen, J, Petersen, J, Larsen, K, and Andersen O.: Predicting mortality in patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome: an evaluation of two prognostic models, two soluble receptors, and a macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2008, 52:1284-1293.

13. Ostrowski SR, Ullum H, Goka BQ, Hoyer-Hansen G, Obeng-Adjei G, Pedersen BK, Akanmori BD, Kurtzhals JA: Plasma concentrations of soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor are increased in patients with malaria and are associated with a poor clinical or a fatal outcome. J Infect Dis 2005, 191(8):1331-1341.

14. Ostrowski SR, Ravn P, Hoyer-Hansen G, Ullum H, Andersen AB: Elevated levels of soluble urokinase receptor in serum from mycobacteria infected patients: still looking for a marker of treatment efficacy. Scand J Infect Dis 2006, 38(11-12):1028-1032.

15. Eugen-Olsen J, Gustafson P, Sidenius N, Fischer TK, Parner J, Aaby P, Gomes VF, Lisse I: The serum level of soluble urokinase receptor is elevated in tuberculosis patients and predicts mortality during treatment: a community study from Guinea-Bissau. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2002, 6(8):686-692.

16. Ostrowski SR, Piironen T, Hoyer-Hansen G, Gerstoft J, Pedersen BK, Ullum H: High plasma levels of intact and cleaved soluble urokinase receptor reflect immune activation and are independent predictors of mortality in HIV-1-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005, 39(1):23-31.

17. Rabna P, Andersen A, Wejse C, Oliveira I, Gomes VF, Haaland MB, Aaby P, Eugen-Olsen J: High mortality risk among individuals assumed to be TB-negative can be predicted using a simple test. Trop Med Int Health 2009, 14(9):986-994.

18. Ostrowski SR, Katzenstein TL, Piironen T, Gerstoft J, Pedersen BK, Ullum H: Soluble urokinase receptor levels in plasma during 5 years of highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2004, 35(4):337-342.

19. Lawn SD, Myer L, Bangani N, Vogt M, Wood R: Plasma levels of soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) and early mortality risk among patients enrolling for antiretroviral treatment in South Africa. BMC Infect Dis 2007, 7:41.

20. Sidenius N, Sier CF, Ullum H, Pedersen BK, Lepri AC, Blasi F, Eugen-Olsen J: Serum level of soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor is a strong and independent predictor of survival in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood 2000, 96(13):4091-4095.

Footnotes

[1] Mammary gland involution is a complex, multi-step process in which the lactating gland is remodeled into a morphological state almost indistinguishable from its pre-pregnancy condition. This is of considerable interest because the process involves many elements common to tissue/organ regeneration in reptiles and amphibians.

[2] CRP=C-Reactive Protein, TNF-a=Tumor Necrosis Factor –alpha, MIF=, s-TREM-1= Soluble Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 1, MIF= Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor, GM-CSF=Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony Stimulating Factor, ILs= interlukins= IL-1 , IL-6, IL-8.

[3] Not only do filtered cigarettes do nothing to reduce the risk of disease from smoking, the first generation “filter tipped” cigarettes contained asbestos and other pro-carcinogens. The number one risk of developing asbestos related cancers such as mesothelioma is tobacco abuse!

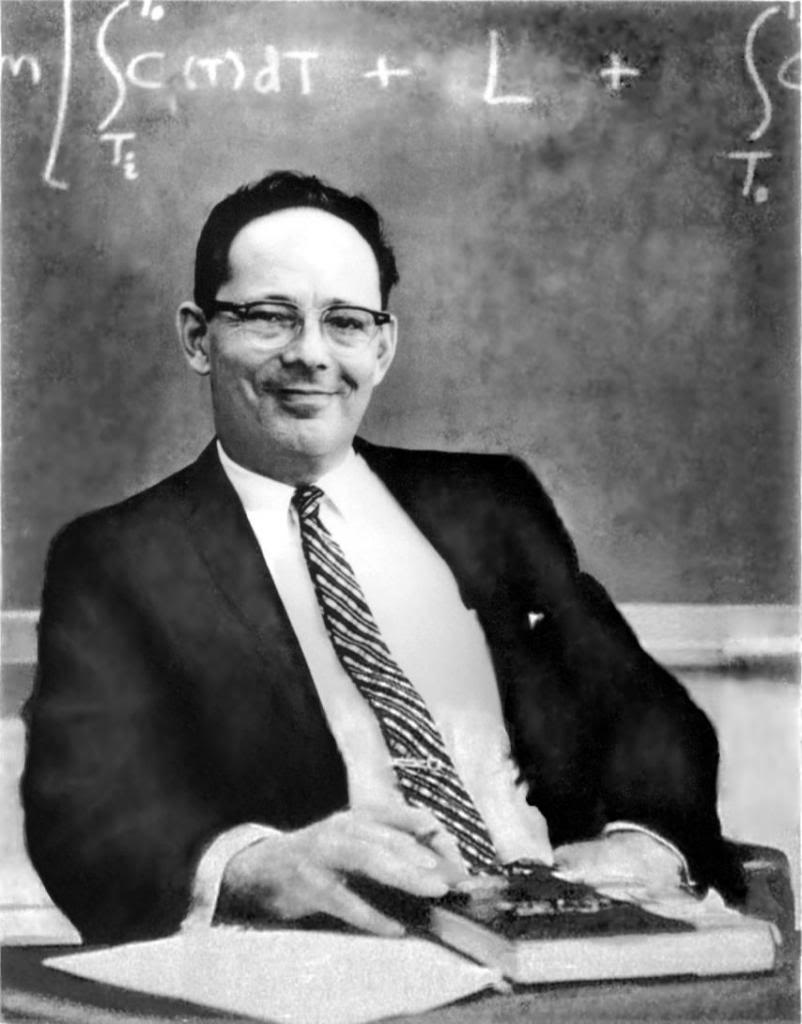

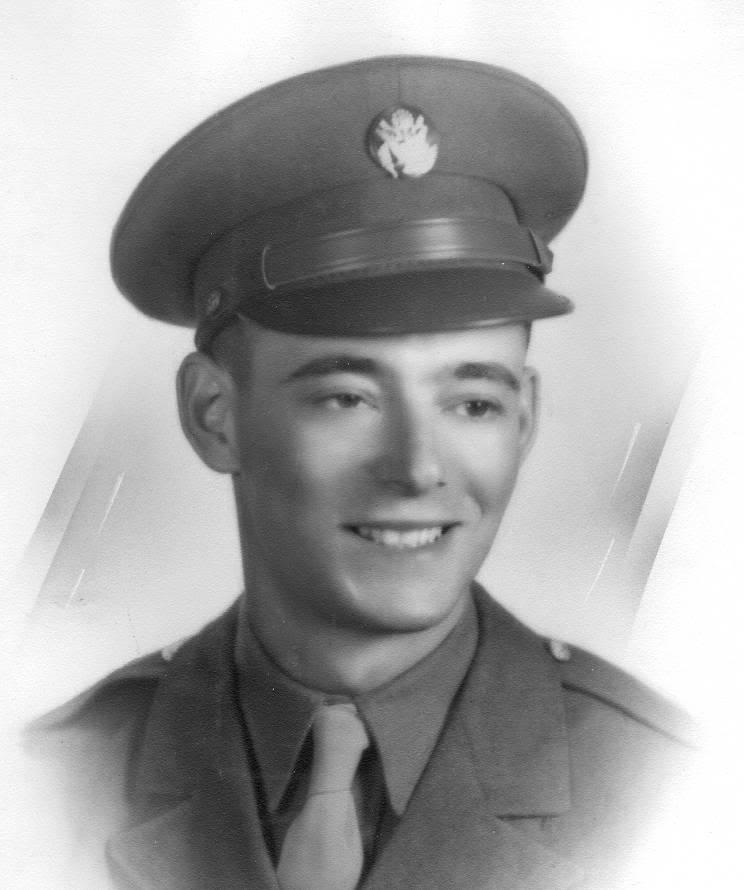

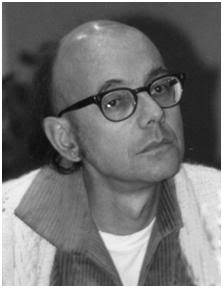

Robert Ettinger as young boy.

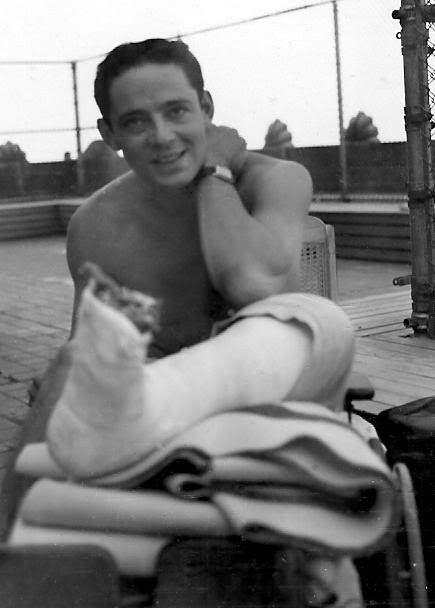

Robert Ettinger as young boy. Ettinger recovering from war wounds around the time he conceived of the idea of cryonics.

Ettinger recovering from war wounds around the time he conceived of the idea of cryonics.

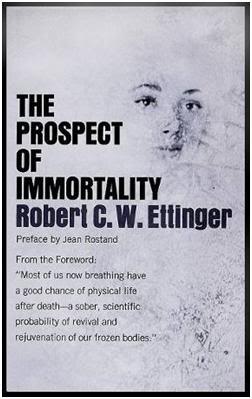

The Prospect of Immortality was published in hardcover by Doubleday in 1964.

The Prospect of Immortality was published in hardcover by Doubleday in 1964. Ettinger on the “Tonight Show with Johnny Carson” in 1966.

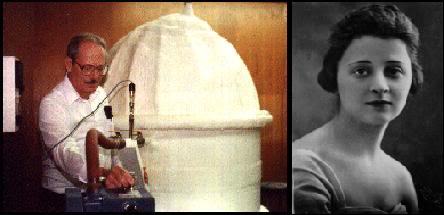

Ettinger on the “Tonight Show with Johnny Carson” in 1966. At left above, Ettinger with his mother’s cryostat in the mid-1980s and at right, Rhea Chaloff Ettinger, Robert Ettinger’s mother as a young woman.

At left above, Ettinger with his mother’s cryostat in the mid-1980s and at right, Rhea Chaloff Ettinger, Robert Ettinger’s mother as a young woman. Robert Ettinger at the Cryonics Institute (CI) in 2009, with photos of some of some of the patients in CI’s care visible in the background. Photo by Chris Asadian

Robert Ettinger at the Cryonics Institute (CI) in 2009, with photos of some of some of the patients in CI’s care visible in the background. Photo by Chris Asadian

Figure 1: The Alcor facility in Riverside, California at night in June of 1987.

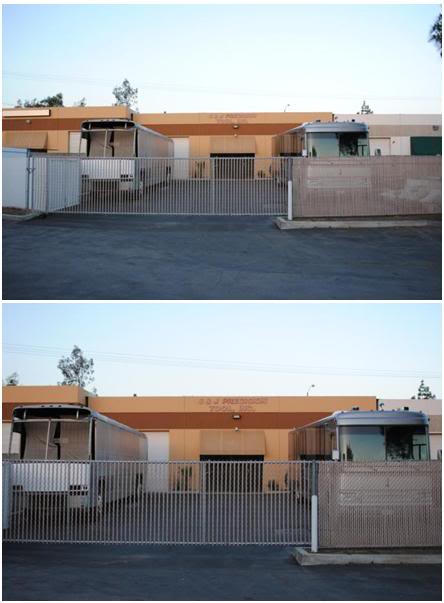

Figure 1: The Alcor facility in Riverside, California at night in June of 1987. Figure 2: Two views of the building once occupied by Alcor as it appeared in April of 2010 just before sunset. Two large motor homes, apparently undergoing renovation, sit in the parking lot obscuring much of the front of the building. Photos by Stanislaw Lipin.

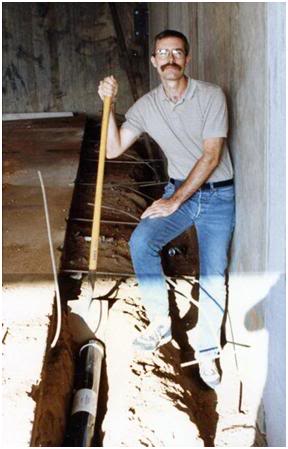

Figure 2: Two views of the building once occupied by Alcor as it appeared in April of 2010 just before sunset. Two large motor homes, apparently undergoing renovation, sit in the parking lot obscuring much of the front of the building. Photos by Stanislaw Lipin. Figure 3: Mike Darwin, shovel in hand, standing next to the Alcor Time Capsule which was buried in the footing of the Doherty Street building in September of 1986.

Figure 3: Mike Darwin, shovel in hand, standing next to the Alcor Time Capsule which was buried in the footing of the Doherty Street building in September of 1986. Figure 4: Front exterior of the Alcor facility in Riverside, CA on 12May, 1987 shortly after Alcor moved into the building. The vehicle bay which housed the Alcor ambulance is on the left and the patient care bay which house Alcor’s patients is on the right of the photo above.

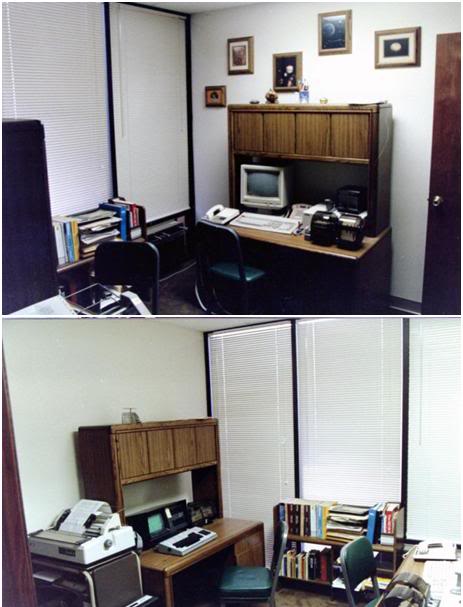

Figure 4: Front exterior of the Alcor facility in Riverside, CA on 12May, 1987 shortly after Alcor moved into the building. The vehicle bay which housed the Alcor ambulance is on the left and the patient care bay which house Alcor’s patients is on the right of the photo above. Figure 5: The reception area of the Alcor facility.

Figure 5: The reception area of the Alcor facility. Figure 6: The reception area looking in towards the interior of the building. That there were three Alcor patients at this time is easy to infer from the three photos of patients above the commissary cart.

Figure 6: The reception area looking in towards the interior of the building. That there were three Alcor patients at this time is easy to infer from the three photos of patients above the commissary cart.

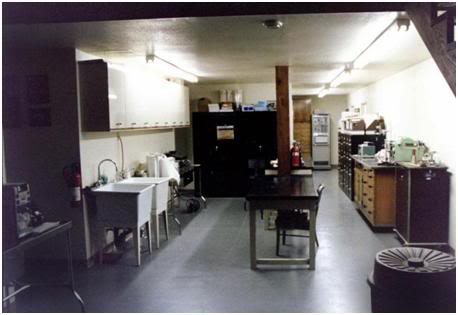

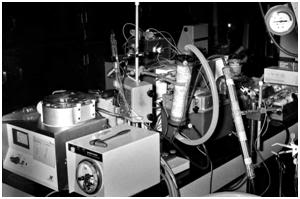

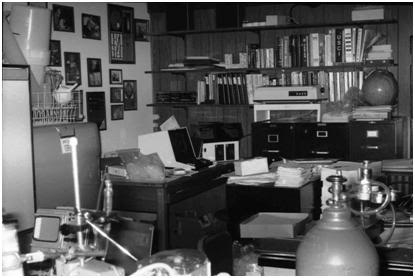

Figure 9: The central work area where solutions were mixed, equipment checked and assembled, and where Cryonics magazine was pasted-up each month prior to being taken to the printer. The Alcor administrative files were in the black filing cabinets visible at the right of the photo.

Figure 9: The central work area where solutions were mixed, equipment checked and assembled, and where Cryonics magazine was pasted-up each month prior to being taken to the printer. The Alcor administrative files were in the black filing cabinets visible at the right of the photo. Figure 10: The central work area extended in front the patient care bay and opened into it.

Figure 10: The central work area extended in front the patient care bay and opened into it. Figure 11: The stairway in Figure 1o led to a loft that was used for the storage of equipment and supplies, as a conference area and for additional office space.

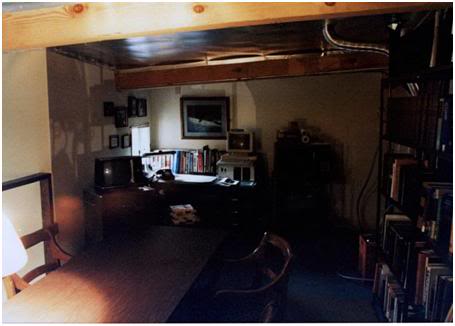

Figure 11: The stairway in Figure 1o led to a loft that was used for the storage of equipment and supplies, as a conference area and for additional office space.  Figure 12: Conference/eating area, Mike Darwin’s office and some of the Alcor library in the loft. The small window at the left my desk opened into the patient care bay.

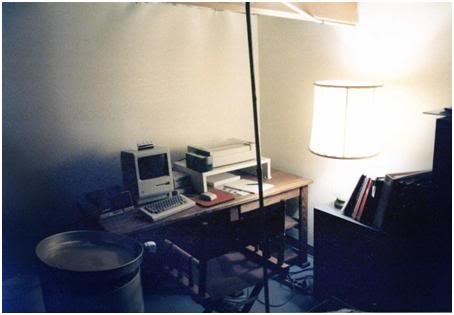

Figure 12: Conference/eating area, Mike Darwin’s office and some of the Alcor library in the loft. The small window at the left my desk opened into the patient care bay. Figure 13: The “art office” where custom illustrations for Cryonics magazine were prepared using an Apple Macintosh computer and dot-matrix printer.

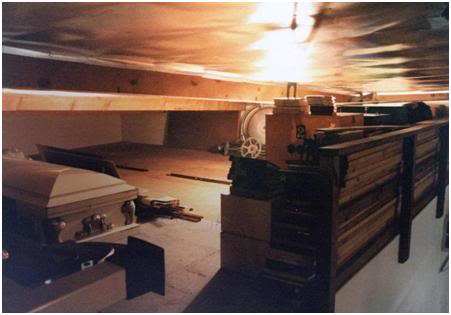

Figure 13: The “art office” where custom illustrations for Cryonics magazine were prepared using an Apple Macintosh computer and dot-matrix printer. Figure 14: The loft space over the operating room was ultimately use to store infrequently used hardware and building supplies. In May of 1987 the most prominent fixture was a metal casket lined with foam and containing a metal air shipping box which served as the cooling bath for chilling whole body patients to dry ice temperature.

Figure 14: The loft space over the operating room was ultimately use to store infrequently used hardware and building supplies. In May of 1987 the most prominent fixture was a metal casket lined with foam and containing a metal air shipping box which served as the cooling bath for chilling whole body patients to dry ice temperature.  Figure 15: The bulk of the loft space was used to store biomedical equipment and supplies to support the operating room.

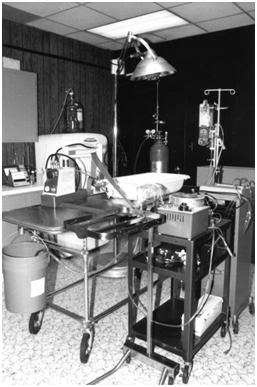

Figure 15: The bulk of the loft space was used to store biomedical equipment and supplies to support the operating room. Fire 16: Two views of the operating room: note the 15,000 BTU air conditioner in the upper left of the photo, which opened exhausted its heat into the central work area.

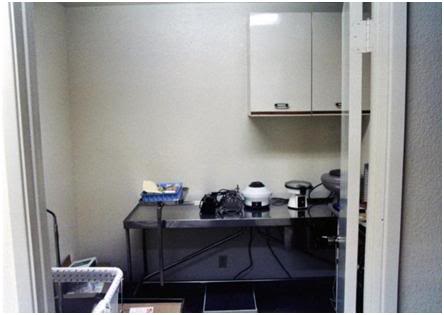

Fire 16: Two views of the operating room: note the 15,000 BTU air conditioner in the upper left of the photo, which opened exhausted its heat into the central work area. Figure 17: Acute post-operative care and ICU room.

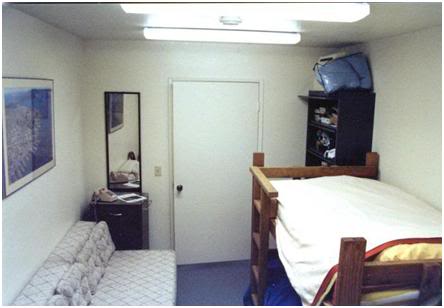

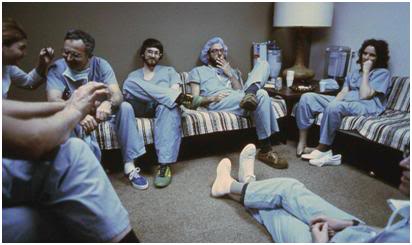

Figure 17: Acute post-operative care and ICU room. Figure 18: The crew room where personnel could sleep during lengthily experiments. This room ultimately became the permanent residence of Hugh Hixon and Mike Perry.

Figure 18: The crew room where personnel could sleep during lengthily experiments. This room ultimately became the permanent residence of Hugh Hixon and Mike Perry. Figure 19: The laundry and utility room of the facility; it also housed a second toilet.

Figure 19: The laundry and utility room of the facility; it also housed a second toilet. Figure 20: The patient care bay with one neuro-vault, one upright MVE dual patient dewar (not in service) and the horizontal dewar containing James Bedford (barely visible at the lower right of the photo).

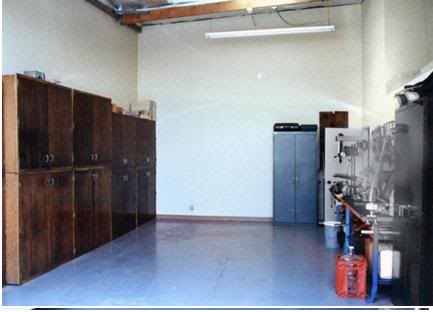

Figure 20: The patient care bay with one neuro-vault, one upright MVE dual patient dewar (not in service) and the horizontal dewar containing James Bedford (barely visible at the lower right of the photo). Figure 21: Vehicle bay and shop also served as the chemicals storage area.

Figure 21: Vehicle bay and shop also served as the chemicals storage area. Figure 22: The shop.

Figure 22: The shop. Figure 23: The Alcor ambulance with the Mobile Advanced Life Support System (MALSS) cart just visible in the open rear doors.

Figure 23: The Alcor ambulance with the Mobile Advanced Life Support System (MALSS) cart just visible in the open rear doors. Figure 24: Former pilot Curtis Henderson prepares for a flight on an ultra-light aircraft as Mike Darwin looks on; his first time aboard a plane of any kind in many years.

Figure 24: Former pilot Curtis Henderson prepares for a flight on an ultra-light aircraft as Mike Darwin looks on; his first time aboard a plane of any kind in many years. Figure 25: Some of the attendees of the Grand Opening at a local Riverside eatery.

Figure 25: Some of the attendees of the Grand Opening at a local Riverside eatery. Figure 26: From left to right with faces to the camera: Thomas Donaldson, Fred Chamberlain, Linda Chamberlain and Billy Seidel (in profile).

Figure 26: From left to right with faces to the camera: Thomas Donaldson, Fred Chamberlain, Linda Chamberlain and Billy Seidel (in profile). Figure 27: Parking jam in back of Saul Kent’s Riverside home in Woodcrest.

Figure 27: Parking jam in back of Saul Kent’s Riverside home in Woodcrest. Figure 28: Left to right: Arel Lucas, Steve Harris, Virginia Gregory, Hugh Hixon, Keith Henson and David London.

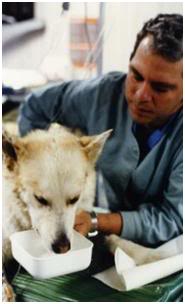

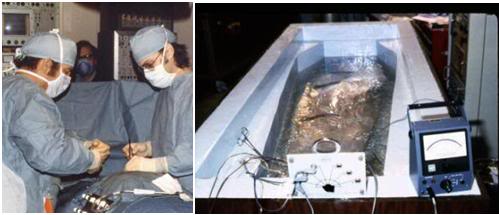

Figure 28: Left to right: Arel Lucas, Steve Harris, Virginia Gregory, Hugh Hixon, Keith Henson and David London. Figure 1: Enkidu, Alcor/Cryovita canine total body washout (TBW) # 2. At top, Enkidu lies chilled to ~5○C, his blood replaced with a specially designed preservative solution (perfusate), near the end of his 4-hours of cold, bloodless perfusion. The perfusate used was hyperosmolar and this resulted in dehydration of the aqueous and vitreous humors of the eyes resulting in ocular dehydration given the globes of the eyes of a flaccid and sunken appearance. Below, Enkidu 24 hours after reperfusion with blood and rewarming to normothermia.

Figure 1: Enkidu, Alcor/Cryovita canine total body washout (TBW) # 2. At top, Enkidu lies chilled to ~5○C, his blood replaced with a specially designed preservative solution (perfusate), near the end of his 4-hours of cold, bloodless perfusion. The perfusate used was hyperosmolar and this resulted in dehydration of the aqueous and vitreous humors of the eyes resulting in ocular dehydration given the globes of the eyes of a flaccid and sunken appearance. Below, Enkidu 24 hours after reperfusion with blood and rewarming to normothermia.  Figure 2: The first human cryonics case done at Cryovita Laboratories on 14 July, 1978 prompted a visit from the Fullerton police and the Orange County Coroner. Only photos were taken and footprints left behind. No harm was done to cryonics or to its patients in the process…

Figure 2: The first human cryonics case done at Cryovita Laboratories on 14 July, 1978 prompted a visit from the Fullerton police and the Orange County Coroner. Only photos were taken and footprints left behind. No harm was done to cryonics or to its patients in the process…

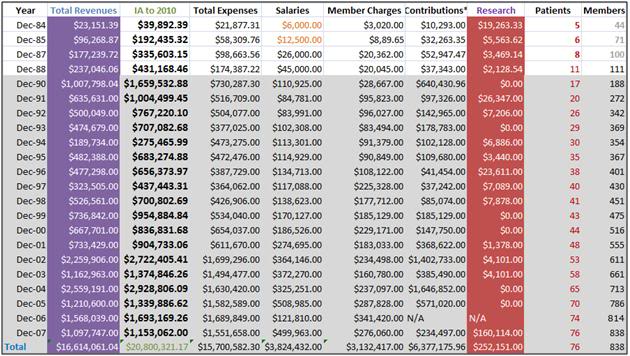

Figure 4: Spreadsheet of some of Alcor’s financial parameters from fiscal year ending 1984 through the end of fiscal year 2007. The total revenues column in highlighted in purple and the expenditures for research column is highlighted in red. Expemditures for research as a fraction of total revenues declined dramatically after the Dora Kent crisis in 1988. In the ensuing 19 year expenditure for research remained a tiny fraction of Alcor’s total revenues, and with the exception of three years, failed to even approach in absolute dollar amounts the yearly disbursements for research in the years prior to 1988.

Figure 4: Spreadsheet of some of Alcor’s financial parameters from fiscal year ending 1984 through the end of fiscal year 2007. The total revenues column in highlighted in purple and the expenditures for research column is highlighted in red. Expemditures for research as a fraction of total revenues declined dramatically after the Dora Kent crisis in 1988. In the ensuing 19 year expenditure for research remained a tiny fraction of Alcor’s total revenues, and with the exception of three years, failed to even approach in absolute dollar amounts the yearly disbursements for research in the years prior to 1988.  Figure 5: Alcor’s all-volunteer research team provided an otherwise unaffordable asset in the form of thousands of hours of contributed labor in support of Alcor’s various research undertakings.

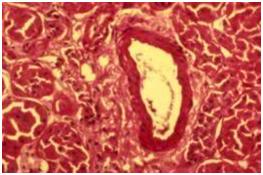

Figure 5: Alcor’s all-volunteer research team provided an otherwise unaffordable asset in the form of thousands of hours of contributed labor in support of Alcor’s various research undertakings.  Beginning in 1982, Alcor continued the research to establish the degree to which ultrastructure was being preserved using existing human cryopreservation techniques begun by IABS in the late 1970s. The work at IABS employed rabbits, however it was decided to use cats as the experimental animals in the Alcor work because of the previous work done on brain cryopreservation by Isamu Suda and because it was anticipated that this work would progress to the evaluation of brain viability using electrophysiology – a model that was, at that time, largely confined to the cat. This research disclosed a number of previously unknown and unexpected findings, including the presence of macroscopic fractures in the animals as a result of cooling to below the glass transition point (Tg) of the water-cryoprotectant solution present in the tissues, as well as much more serious ultrastructural disruption due to freezing damage, than was previously expected. This work constituted the first comprehensive evaluation of human cryopreservation techniques and was also the first to examine the effects of ischemia on cryopreservation injury.

Beginning in 1982, Alcor continued the research to establish the degree to which ultrastructure was being preserved using existing human cryopreservation techniques begun by IABS in the late 1970s. The work at IABS employed rabbits, however it was decided to use cats as the experimental animals in the Alcor work because of the previous work done on brain cryopreservation by Isamu Suda and because it was anticipated that this work would progress to the evaluation of brain viability using electrophysiology – a model that was, at that time, largely confined to the cat. This research disclosed a number of previously unknown and unexpected findings, including the presence of macroscopic fractures in the animals as a result of cooling to below the glass transition point (Tg) of the water-cryoprotectant solution present in the tissues, as well as much more serious ultrastructural disruption due to freezing damage, than was previously expected. This work constituted the first comprehensive evaluation of human cryopreservation techniques and was also the first to examine the effects of ischemia on cryopreservation injury.

By carrying out autopsies and conducting histological and ultrastructural studies on the bodies of human patients converted from whole body cryopreservation to neurocryopreservation, Alcor was the first to discover that the macroscopic fracturing of organs and tissues that were occurring in experimental animals were also occurring in human patients. This work demonstrated that existing perfusion techniques were not delivering an adequate amount of cryoprotectant to the tissues. It was also the first demonstration that at the histological level, 3M glycerol was effective in preserving tissue architecture in a state indistinguishable from that of seen in unfrozen humans.

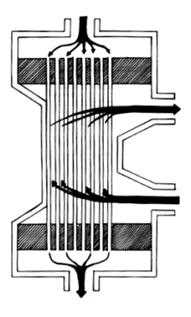

By carrying out autopsies and conducting histological and ultrastructural studies on the bodies of human patients converted from whole body cryopreservation to neurocryopreservation, Alcor was the first to discover that the macroscopic fracturing of organs and tissues that were occurring in experimental animals were also occurring in human patients. This work demonstrated that existing perfusion techniques were not delivering an adequate amount of cryoprotectant to the tissues. It was also the first demonstration that at the histological level, 3M glycerol was effective in preserving tissue architecture in a state indistinguishable from that of seen in unfrozen humans. Alcor research demonstrated that hollow fiber dialyzers could be effectively used as oxygenators for extracorporeal support of animals, including adult ~25 kg dogs. This work was conducted 4 years before the first hollow fiber blood oxygenators entered clinical trials and five years before they entered routine clinical use.[21, 22]

Alcor research demonstrated that hollow fiber dialyzers could be effectively used as oxygenators for extracorporeal support of animals, including adult ~25 kg dogs. This work was conducted 4 years before the first hollow fiber blood oxygenators entered clinical trials and five years before they entered routine clinical use.[21, 22]

Alcor also pioneered pharmacotherapy to mitigate the ischemia-reperfusion injury cryonics patients necessarily suffer as a result of having to wait for the pronouncement of medico-legal death prior to the start of the procedure.

Alcor also pioneered pharmacotherapy to mitigate the ischemia-reperfusion injury cryonics patients necessarily suffer as a result of having to wait for the pronouncement of medico-legal death prior to the start of the procedure. Alcor applied research led to the development of a field-able platform for rapid post-cardiac arrest extracorporeal support of cryonics patients.

Alcor applied research led to the development of a field-able platform for rapid post-cardiac arrest extracorporeal support of cryonics patients.

Alcor pioneered high efficiency storage for cryonics patients with the use of the MVE A-2542 cryogenic dewar for storing neuropatients and the subsequent development of the “bigfoot” dewar which can store four whole body patients and 4 neuropatients. Alcor was the first cryonics organization to offer seismic, ballistic and blast protection to its patients with the development of the “neurovault” in 1984.

Alcor pioneered high efficiency storage for cryonics patients with the use of the MVE A-2542 cryogenic dewar for storing neuropatients and the subsequent development of the “bigfoot” dewar which can store four whole body patients and 4 neuropatients. Alcor was the first cryonics organization to offer seismic, ballistic and blast protection to its patients with the development of the “neurovault” in 1984.

Alcor engaged in considerable charity work during the 1980s taking over the care of three unfunded patients and assisting two other patients with inadequate funding into cryopreservation. This record of charitable cryogenic care of patients in need is unique to Alcor through to the present.

Alcor engaged in considerable charity work during the 1980s taking over the care of three unfunded patients and assisting two other patients with inadequate funding into cryopreservation. This record of charitable cryogenic care of patients in need is unique to Alcor through to the present.

Wowk, BW, The death of death in cryonics. Cryonics. 9(6);30-71:988:

Wowk, BW, The death of death in cryonics. Cryonics. 9(6);30-71:988:  Darwin, MG. Transport Protocol for Cryonic suspension of Humans. Alcor Life Extension Foundation, Fullerton, CA, 1986.

Darwin, MG. Transport Protocol for Cryonic suspension of Humans. Alcor Life Extension Foundation, Fullerton, CA, 1986.  This period was also one of great growth in the technology for providing in-field support of patients experiencing cardiac arrest remote from Alcor’s facilities. Alcor conceived of an implemented the idea of remote standby and was the first cryonics organization to offer extended extracorporeal support during ultraprofound hypothermic transport of patients.

This period was also one of great growth in the technology for providing in-field support of patients experiencing cardiac arrest remote from Alcor’s facilities. Alcor conceived of an implemented the idea of remote standby and was the first cryonics organization to offer extended extracorporeal support during ultraprofound hypothermic transport of patients.

On 21 March, 1978 the Cryonics Institute (CI) acquired their first facility, a storefront building in the Detroit Metro area. The CI building was the first wholly owned (cash purchase) patient storage facility in the history of cryonics, and remains one of only two in the world today. The May, 1978 issue of the Immortalist Society newsletter, The Immortalist, described the facility thusly:

On 21 March, 1978 the Cryonics Institute (CI) acquired their first facility, a storefront building in the Detroit Metro area. The CI building was the first wholly owned (cash purchase) patient storage facility in the history of cryonics, and remains one of only two in the world today. The May, 1978 issue of the Immortalist Society newsletter, The Immortalist, described the facility thusly: Above: The CI facility as seen from the street corner a block away in Detroit Michigan.

Above: The CI facility as seen from the street corner a block away in Detroit Michigan. Above: The first CI facility was quite small and was tucked in between other businesses in a residential area of Detroit.

Above: The first CI facility was quite small and was tucked in between other businesses in a residential area of Detroit.  Above: The entrance to the CI facility in 1978.

Above: The entrance to the CI facility in 1978. Above: The rear of the CI facility in 1978.

Above: The rear of the CI facility in 1978. Above: CI’s first cryostat. This cryostat was fabricated in CI’s first facility by Andy Zawacki and Robert Ettinger, and was later transported to their second, much larger facility in Clinton Township (see below). Photo by Taryn Simon, 2008.

Above: CI’s first cryostat. This cryostat was fabricated in CI’s first facility by Andy Zawacki and Robert Ettinger, and was later transported to their second, much larger facility in Clinton Township (see below). Photo by Taryn Simon, 2008. Above and below: American Cryonics Society (ACS) patient being readied for cool-down to liquid nitrogen temperature. Control of temperature descent was by slowly lowering the patient towards a pool of liquid nitrogen in the bottom of rectangular, vacuum insulated fiberglass and epoxy resin cryostat. Above, Robert Ettinger (left) and Andy Zawacki (right) and below. Robert Ettinger (far right) and Andy Zawacki (right). Photos by Jim Yount.

Above and below: American Cryonics Society (ACS) patient being readied for cool-down to liquid nitrogen temperature. Control of temperature descent was by slowly lowering the patient towards a pool of liquid nitrogen in the bottom of rectangular, vacuum insulated fiberglass and epoxy resin cryostat. Above, Robert Ettinger (left) and Andy Zawacki (right) and below. Robert Ettinger (far right) and Andy Zawacki (right). Photos by Jim Yount.

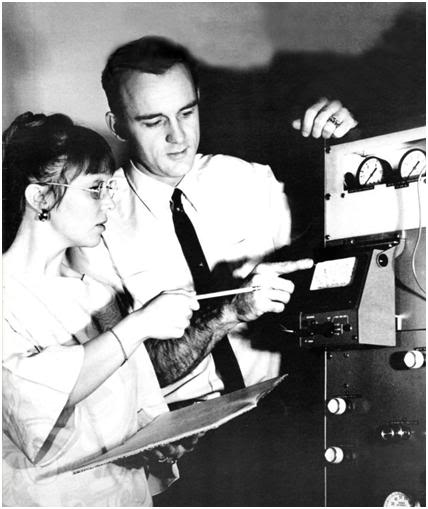

Figure 1: Fred and Linda Chamberlain with an early prototype perfusion machine.

Figure 1: Fred and Linda Chamberlain with an early prototype perfusion machine. Figure 2: Fred and Linda Chamberlain with Fred’s father, Frederick Rockwell Chamberlain, Jr., in December of 1974.

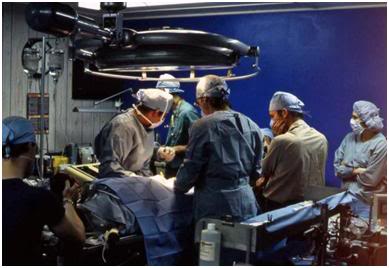

Figure 2: Fred and Linda Chamberlain with Fred’s father, Frederick Rockwell Chamberlain, Jr., in December of 1974. Figure 3: Operating room of Soma, Inc., and the Institute for Advanced Biological Studies (IABS) in Indianapolis, IN in 1979.

Figure 3: Operating room of Soma, Inc., and the Institute for Advanced Biological Studies (IABS) in Indianapolis, IN in 1979. Figure 4: The entrance to Cryovita Laboratories located at 4030 N. Palm, Unit 304 in Fullerton, CA circa 1979.

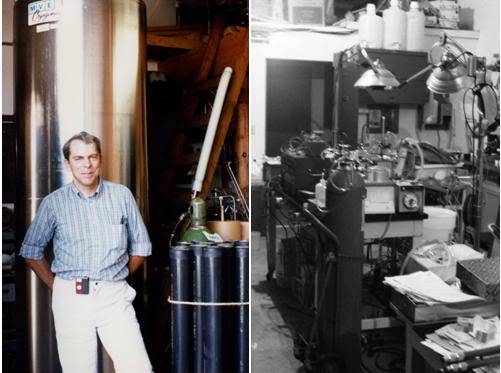

Figure 4: The entrance to Cryovita Laboratories located at 4030 N. Palm, Unit 304 in Fullerton, CA circa 1979. Figure 5: Cryovita occupied a small, impossibly cramped industrial bay in Fullerton, California. Animal research and human cryonics cases were carried out using the same facilities. At left, above, Jerry Leaf stands next to Alcor’s first dual patient cryogenic dewar, proudly sporting the MVE logo.

Figure 5: Cryovita occupied a small, impossibly cramped industrial bay in Fullerton, California. Animal research and human cryonics cases were carried out using the same facilities. At left, above, Jerry Leaf stands next to Alcor’s first dual patient cryogenic dewar, proudly sporting the MVE logo. Figure 6: With the exception of the operating room and the office/reception area, the bay was neither subdivided not heated or cooled. It was often miserably cold in the winter (~ 15○C) and brutally hot in the summer. Dust, which poured in from over and around the roll-up door at the back of the bay and through the skylight, was a constant problem.Above is the Alcor office at appeared in 1983.

Figure 6: With the exception of the operating room and the office/reception area, the bay was neither subdivided not heated or cooled. It was often miserably cold in the winter (~ 15○C) and brutally hot in the summer. Dust, which poured in from over and around the roll-up door at the back of the bay and through the skylight, was a constant problem.Above is the Alcor office at appeared in 1983. Figure 7: Before the operating room was constructed, patient cryopreservations and research work were conducted in the undivided industrial bay. Wiring was makeshift, comfort was non-existent, and the whole operation functioned on a shoestring. Above, a canine total body washout conducted at Cryovita in 1978 or 1979.

Figure 7: Before the operating room was constructed, patient cryopreservations and research work were conducted in the undivided industrial bay. Wiring was makeshift, comfort was non-existent, and the whole operation functioned on a shoestring. Above, a canine total body washout conducted at Cryovita in 1978 or 1979. Figure 8: The all-volunteer research staff at Cryovita during a canine TBW after the (unsuccessful) experiment circa 1978-79. Left to right: Jerry Leaf (hands), Betty Leaf, Reg Thatcher, Greg Fahy, Tom the Perfusionist, Cath Woof and (barely in frame) Thomas Donaldson.

Figure 8: The all-volunteer research staff at Cryovita during a canine TBW after the (unsuccessful) experiment circa 1978-79. Left to right: Jerry Leaf (hands), Betty Leaf, Reg Thatcher, Greg Fahy, Tom the Perfusionist, Cath Woof and (barely in frame) Thomas Donaldson. Figure 9: A Clay Adams Becton-Dickinson 0151 Analytical Centrifuge of the kind commonly discarded after home-dialysis patients died or returned to –in-center hemodialysis. These units retailed for ~$500 in 1982.

Figure 9: A Clay Adams Becton-Dickinson 0151 Analytical Centrifuge of the kind commonly discarded after home-dialysis patients died or returned to –in-center hemodialysis. These units retailed for ~$500 in 1982. Figure 10: Cryovita was located in an industrial park a few hundred yards from a major Southern California drug wholesale warehouse. Experimental dogs were walked along the concrete wash (photo at lower right) or in the field on the other side of the wash. A red X marks the location of the PRN dumpster where we used to recover discarded medical products. The image is from Google Earth and the building which currently occupies the lot labeled “Dog Exercise Field” has been removed using Photoshop.

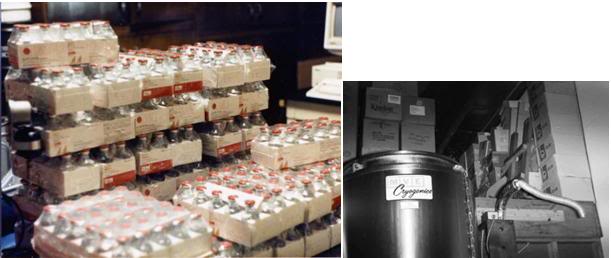

Figure 10: Cryovita was located in an industrial park a few hundred yards from a major Southern California drug wholesale warehouse. Experimental dogs were walked along the concrete wash (photo at lower right) or in the field on the other side of the wash. A red X marks the location of the PRN dumpster where we used to recover discarded medical products. The image is from Google Earth and the building which currently occupies the lot labeled “Dog Exercise Field” has been removed using Photoshop. Figure 11: Above left, dozens of doses of Unipen (nafcillin) parenteral antibiotic recovered from the dumpster of PRN. At right, boxes of perfusion supplies, dialyzers and ethylene oxide sterilization wrap all obtained for free, or at pennies on the dollar. Photo 28 May, 1995.

Figure 11: Above left, dozens of doses of Unipen (nafcillin) parenteral antibiotic recovered from the dumpster of PRN. At right, boxes of perfusion supplies, dialyzers and ethylene oxide sterilization wrap all obtained for free, or at pennies on the dollar. Photo 28 May, 1995. By Mike Darwin

By Mike Darwin

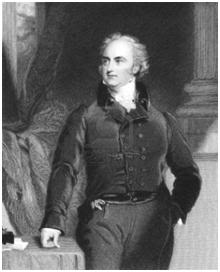

Figure 1: Sir Astley Cooper (1768 –1841).

Figure 1: Sir Astley Cooper (1768 –1841). Figure 2: Today we have antisepsis, anesthesia, and injectable pain killers. Medical and dying have been made seemingly more palatable. But are they, really?

Figure 2: Today we have antisepsis, anesthesia, and injectable pain killers. Medical and dying have been made seemingly more palatable. But are they, really? Figure 3: Then and now: At left above, a tuberculosis (TB) ward in the late 19th or early 20th century was a place fear, loneliness and often little or no hope. A contemporary nursing home (above, right) is little different, except that the people dying there are, on average 30 or 40 years older and they, unlike the TB patients of the previous centuries, know with certainty that for them there will be no escape.

Figure 3: Then and now: At left above, a tuberculosis (TB) ward in the late 19th or early 20th century was a place fear, loneliness and often little or no hope. A contemporary nursing home (above, right) is little different, except that the people dying there are, on average 30 or 40 years older and they, unlike the TB patients of the previous centuries, know with certainty that for them there will be no escape. Figure 4: Death is death; the end result is the same; non-existence and oblivion. It is also an illusion that the horror and suffering are really less today than they were yesterday, or will be tomorrow. If anything, extension of the mean lifespan in the absence of regenerative and rejuvenating medicine extends the period of suffering and increases the terror. The average lifespan of a patient with Alzheimer’s disease is 8 years from diagnosis to death. More people are interned in extended care facilities today than were ever imprisoned at Auschwitz, Dachau, or all the Nazi concentration camps combined. And unlike many patients dying from infectious disease in the previous centuries, patients in nursing homes and care facilities (if they are not demented) know that for them there is no hope of escape. That is a condition that even the Nazis never managed to uniformly impose on their victims.

Figure 4: Death is death; the end result is the same; non-existence and oblivion. It is also an illusion that the horror and suffering are really less today than they were yesterday, or will be tomorrow. If anything, extension of the mean lifespan in the absence of regenerative and rejuvenating medicine extends the period of suffering and increases the terror. The average lifespan of a patient with Alzheimer’s disease is 8 years from diagnosis to death. More people are interned in extended care facilities today than were ever imprisoned at Auschwitz, Dachau, or all the Nazi concentration camps combined. And unlike many patients dying from infectious disease in the previous centuries, patients in nursing homes and care facilities (if they are not demented) know that for them there is no hope of escape. That is a condition that even the Nazis never managed to uniformly impose on their victims. I don’t believe in any magical technological Singularity where we will all wake up someday soon; both immortal and in utopia.

I don’t believe in any magical technological Singularity where we will all wake up someday soon; both immortal and in utopia.

Figure 7: No marker or monument endures and no man’s life, let alone his personal identity, can be written down on paper in words.

Figure 7: No marker or monument endures and no man’s life, let alone his personal identity, can be written down on paper in words. Question: How did God create heaven and earth?

Question: How did God create heaven and earth? The resolution of the images, both real and computer generated (CGI), is superb and unassailable. The credibility of CGI has surpassed that of what is possible when merely capturing reality on film, and by this I mean that the unreal trumps the real and the unbelievable is more credible than the believable. Sitting there dazzled by the sheer beauty of the film’s imagery, it occurred to me why god(s), if there are any, made the universe – because they could realize a place vastly more beautiful and wonderful, and vastly more terrible and dark than the world which they themselves are confined to.

The resolution of the images, both real and computer generated (CGI), is superb and unassailable. The credibility of CGI has surpassed that of what is possible when merely capturing reality on film, and by this I mean that the unreal trumps the real and the unbelievable is more credible than the believable. Sitting there dazzled by the sheer beauty of the film’s imagery, it occurred to me why god(s), if there are any, made the universe – because they could realize a place vastly more beautiful and wonderful, and vastly more terrible and dark than the world which they themselves are confined to. By “nicer” I do not necessarily mean more “pleasant.” There are physical limits imposed by our universe on how much pain, how much suffering, how much physical distortion, disruption and rending of the flesh are possible, before life ceases. It is the sorrow of every sadist and every masochist that the flesh of the body can only be tortured in so few, and so finite ways. What are the implications of that? Perhaps it would be wise for us to reflect on the quote from Milton’s

By “nicer” I do not necessarily mean more “pleasant.” There are physical limits imposed by our universe on how much pain, how much suffering, how much physical distortion, disruption and rending of the flesh are possible, before life ceases. It is the sorrow of every sadist and every masochist that the flesh of the body can only be tortured in so few, and so finite ways. What are the implications of that? Perhaps it would be wise for us to reflect on the quote from Milton’s  The story line of the film captures with perfection the essential values of this culture. The “final” battle between good and evil is played out; Lord Voldemort, whom the author of the Harry Potter books has

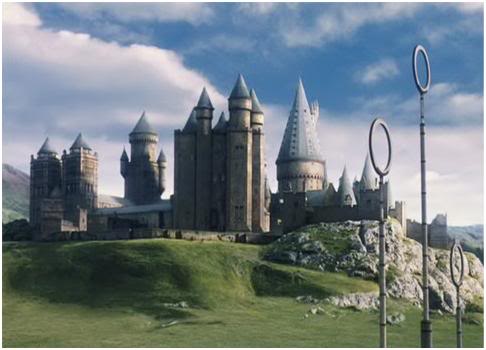

The story line of the film captures with perfection the essential values of this culture. The “final” battle between good and evil is played out; Lord Voldemort, whom the author of the Harry Potter books has  The closing sequence of the film is of Harry Potter and his cohorts as mature men and women living in the everyday world we all inhabit. He has a child now, and it is time to send him off to Hogwarts boarding school to learn the craft of Wizardry. Age has begun to mark Harry Potter, and these scenes are meant to show us that by his deeds, he has ensured and acceded to the triumph of generational mortality. Harry Potter will grow old and die, as will his children, and his children’s children. Immortality is not for men, nor is super-knowledge beyond that already granted to Wizards, which is, of course, vastly greater than that granted to the mere “muggles” whose world they cohabit.

The closing sequence of the film is of Harry Potter and his cohorts as mature men and women living in the everyday world we all inhabit. He has a child now, and it is time to send him off to Hogwarts boarding school to learn the craft of Wizardry. Age has begun to mark Harry Potter, and these scenes are meant to show us that by his deeds, he has ensured and acceded to the triumph of generational mortality. Harry Potter will grow old and die, as will his children, and his children’s children. Immortality is not for men, nor is super-knowledge beyond that already granted to Wizards, which is, of course, vastly greater than that granted to the mere “muggles” whose world they cohabit.

Figure 1: Soluble urokinase plasma receptor (suPAR). Panel A – Schematic representation of the amino acid sequence of human uPAR showing its three homologous LU domains. Consensus disulfide bonds defining the LU domains are coloured black. The position of the C-terminal glycolipid anchor (GPI) is shown (modified from Ploug and Ellis, 1994, with permission). Insert: The archetypical three-finger fold is illustrated by a ribbon diagram for a single secreted LU-domain protein (snake venom toxin-a) using the PDB coordinates 1NEA and PyMOLTM (DeLano Scientific). Panel B – LU domain signatures in the primary sequence of human uPAR. The three LU domains (DI, DII and DIII) of uPAR are aligned with the consensus structures being highlighted (disulfide bonds in yellow and the invariant asparagines in red). The number of residues between the individual cysteines is represented by dots or numbers in brackets (modified from Kjaergaard et al., 2008). Panel C – The crystal structure solved for uPAR in complex with a peptide antagonist is shown as a ribbon diagram (Llinas et al., 2005). The individual LU domains are colour-coded (DI in yellow, DII in blue and DIII in red), and N-linked carbohydrates are shown as white sticks. The attachment to the cell surface by a glycolipid anchor is modelled in this cartoon. The insert shows uPAR in a surface representation, with the hydrophobic ligand-binding cavity marked with hatched lines; carbon, nitrogen and oxygen atoms are coloured white, blue and red, respectively. These structures are visualized by PyMOLTM (DeLano Scientific), using the PDB coordinates 1YWH (reproduced from Kjaergaard et al., 2008).[1]

Figure 1: Soluble urokinase plasma receptor (suPAR). Panel A – Schematic representation of the amino acid sequence of human uPAR showing its three homologous LU domains. Consensus disulfide bonds defining the LU domains are coloured black. The position of the C-terminal glycolipid anchor (GPI) is shown (modified from Ploug and Ellis, 1994, with permission). Insert: The archetypical three-finger fold is illustrated by a ribbon diagram for a single secreted LU-domain protein (snake venom toxin-a) using the PDB coordinates 1NEA and PyMOLTM (DeLano Scientific). Panel B – LU domain signatures in the primary sequence of human uPAR. The three LU domains (DI, DII and DIII) of uPAR are aligned with the consensus structures being highlighted (disulfide bonds in yellow and the invariant asparagines in red). The number of residues between the individual cysteines is represented by dots or numbers in brackets (modified from Kjaergaard et al., 2008). Panel C – The crystal structure solved for uPAR in complex with a peptide antagonist is shown as a ribbon diagram (Llinas et al., 2005). The individual LU domains are colour-coded (DI in yellow, DII in blue and DIII in red), and N-linked carbohydrates are shown as white sticks. The attachment to the cell surface by a glycolipid anchor is modelled in this cartoon. The insert shows uPAR in a surface representation, with the hydrophobic ligand-binding cavity marked with hatched lines; carbon, nitrogen and oxygen atoms are coloured white, blue and red, respectively. These structures are visualized by PyMOLTM (DeLano Scientific), using the PDB coordinates 1YWH (reproduced from Kjaergaard et al., 2008).[1] Figure 2: Schematic representation of urokinase receptor The GPI-anchor links uPAR to the cell membrane making it available for uPA to bind to the receptor. When the receptor is cleaved between the GPI-anchor and D3, it becomes soluble (suPAR). suPAR is a stable protein that can be measured in various body fluids. uPA: urokinase-type plasminogen activator, uPAR: uPA receptor, suPAR: soluble uPAR, 1: Domain 1, D2: Domain 2, D3: Domain 3.

Figure 2: Schematic representation of urokinase receptor The GPI-anchor links uPAR to the cell membrane making it available for uPA to bind to the receptor. When the receptor is cleaved between the GPI-anchor and D3, it becomes soluble (suPAR). suPAR is a stable protein that can be measured in various body fluids. uPA: urokinase-type plasminogen activator, uPAR: uPA receptor, suPAR: soluble uPAR, 1: Domain 1, D2: Domain 2, D3: Domain 3. Figure 3: uPAR ligands. Schematic representation of the functions of uPAR via its interaction with uPA, integrins, and vitronectin (modified from Kjaergaard et al., 2008)[1].

Figure 3: uPAR ligands. Schematic representation of the functions of uPAR via its interaction with uPA, integrins, and vitronectin (modified from Kjaergaard et al., 2008)[1]. Figure 4: The optimum level of circulating suPAR appears to be below 2.0 ng/mL in men and 2.5 ng/mL or lower in women. In the healthy population, risk of disease or death rises sharply as the suPAR level increases. The circulating suPAR level increases sensitively with lifestyle choices know to be associated with increased risk of illness and death, such as tobacco abuse, obesity and a sedentary lifestyle – but not to the same degree in all individuals. In fact, suPARnostic® testing may allow clinicians (and theoretically tobacco companies and smokers) to determine those patients for whom smoking, obesity or other “harmful” lifestyle choices pose much less risk.